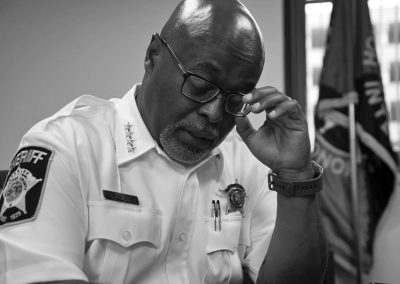

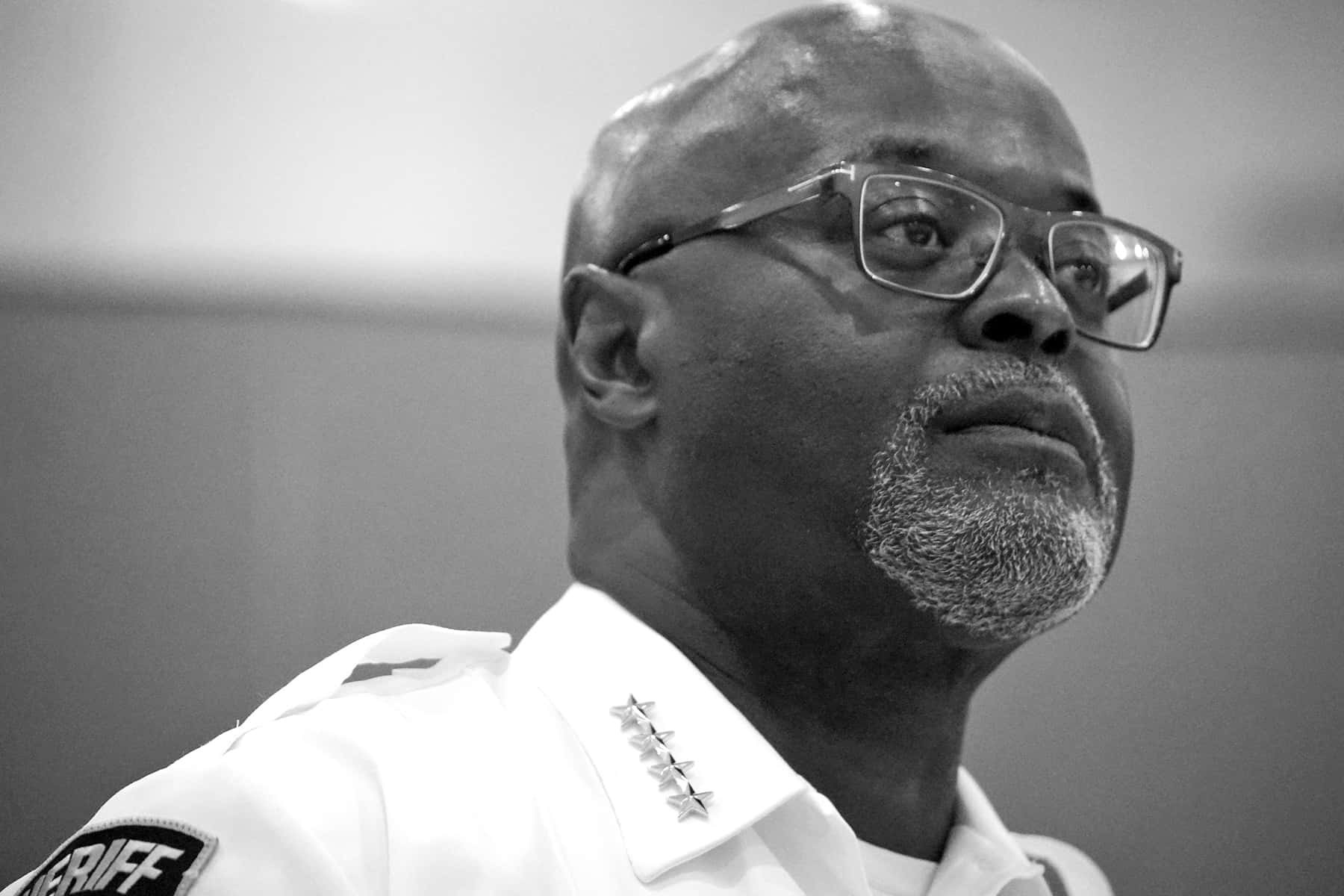

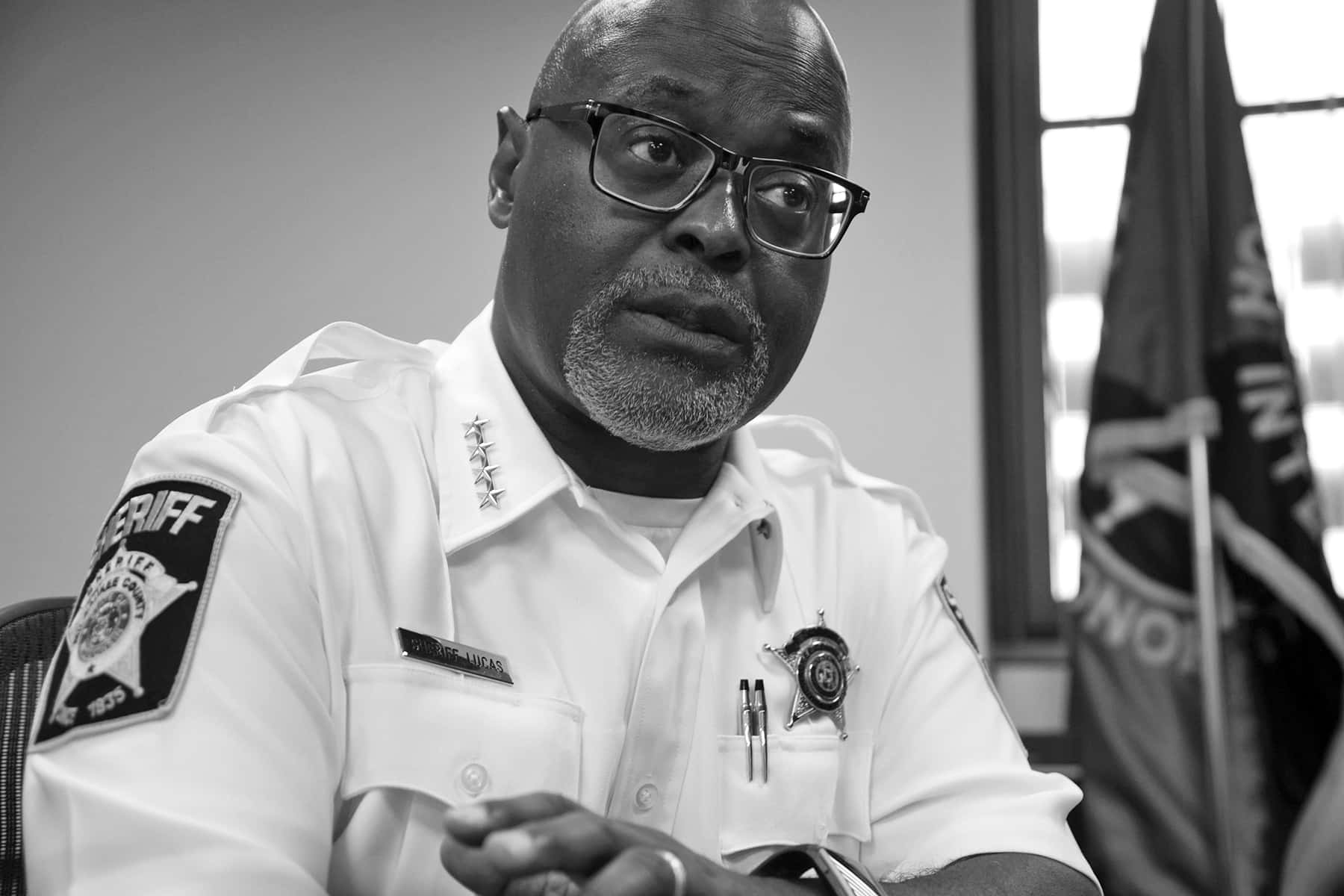

With a lifetime connection to the local community, from being born at the Hillside Housing Project to attending public schools, Earnell Lucas has seen the fabric of his life be woven by personal experiences in Milwaukee.

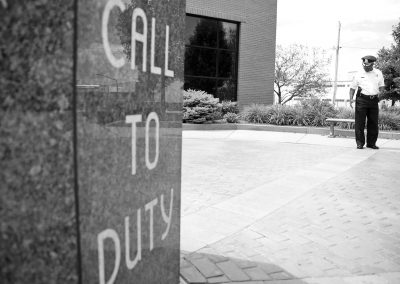

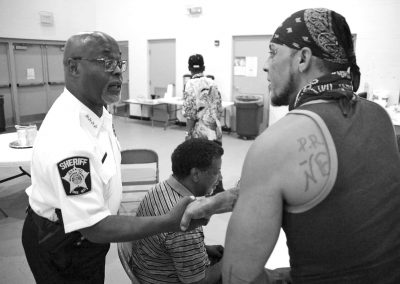

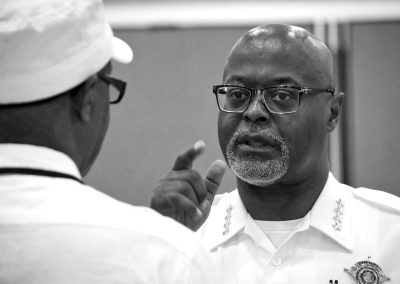

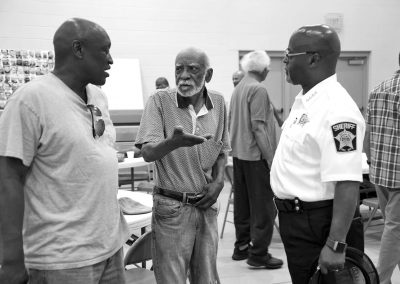

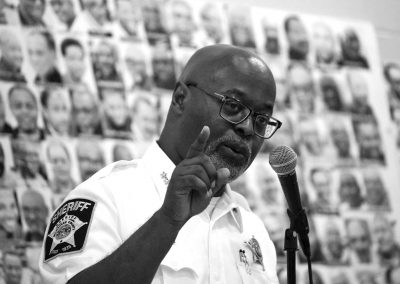

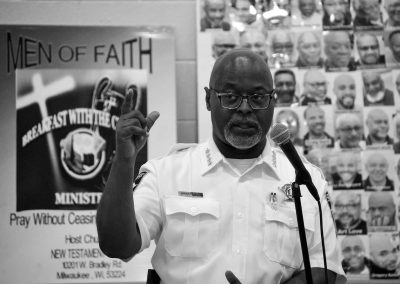

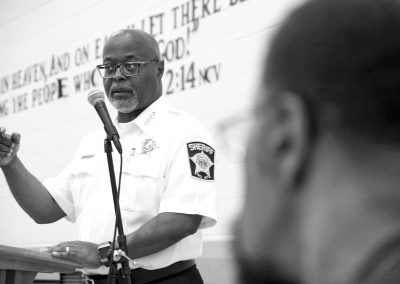

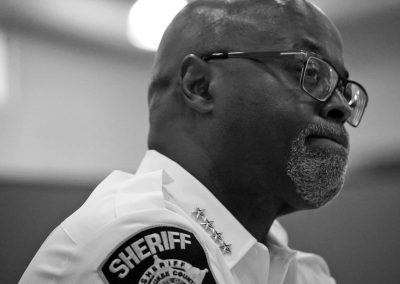

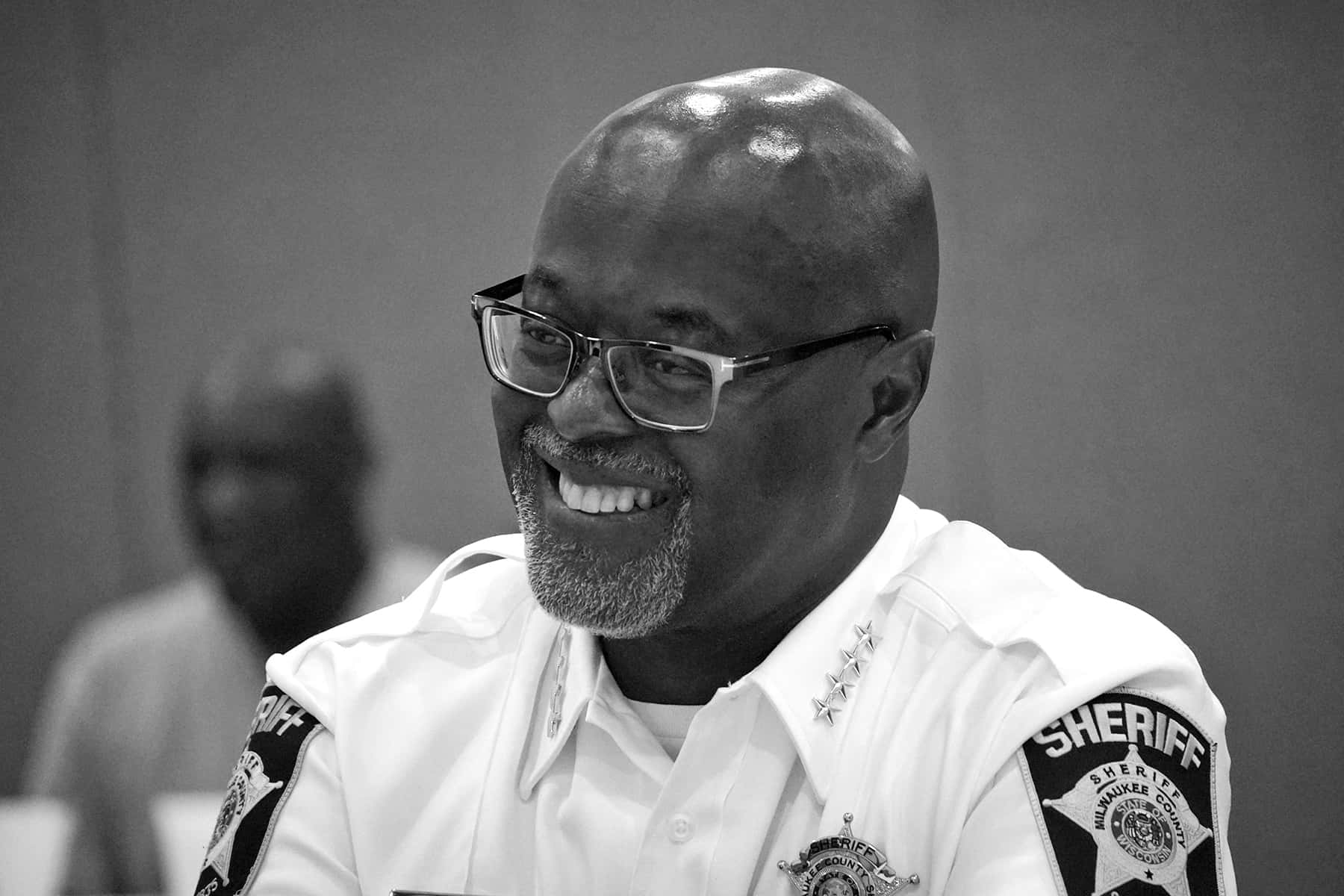

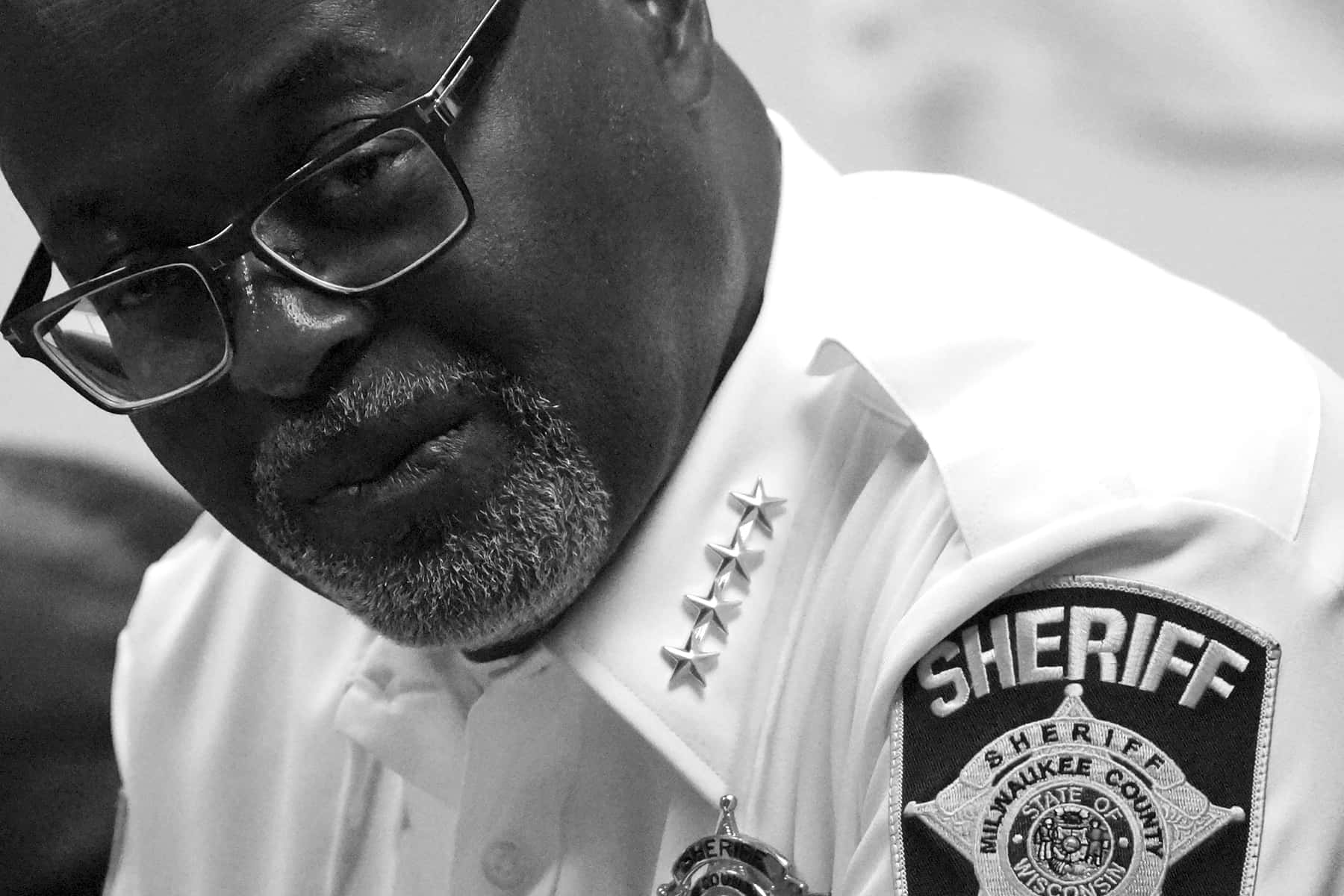

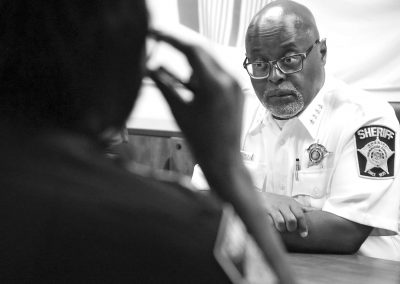

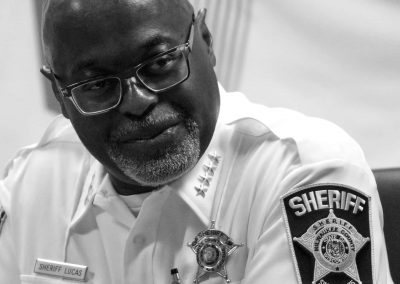

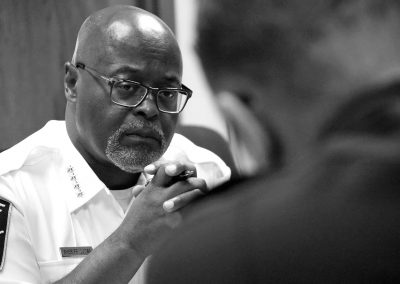

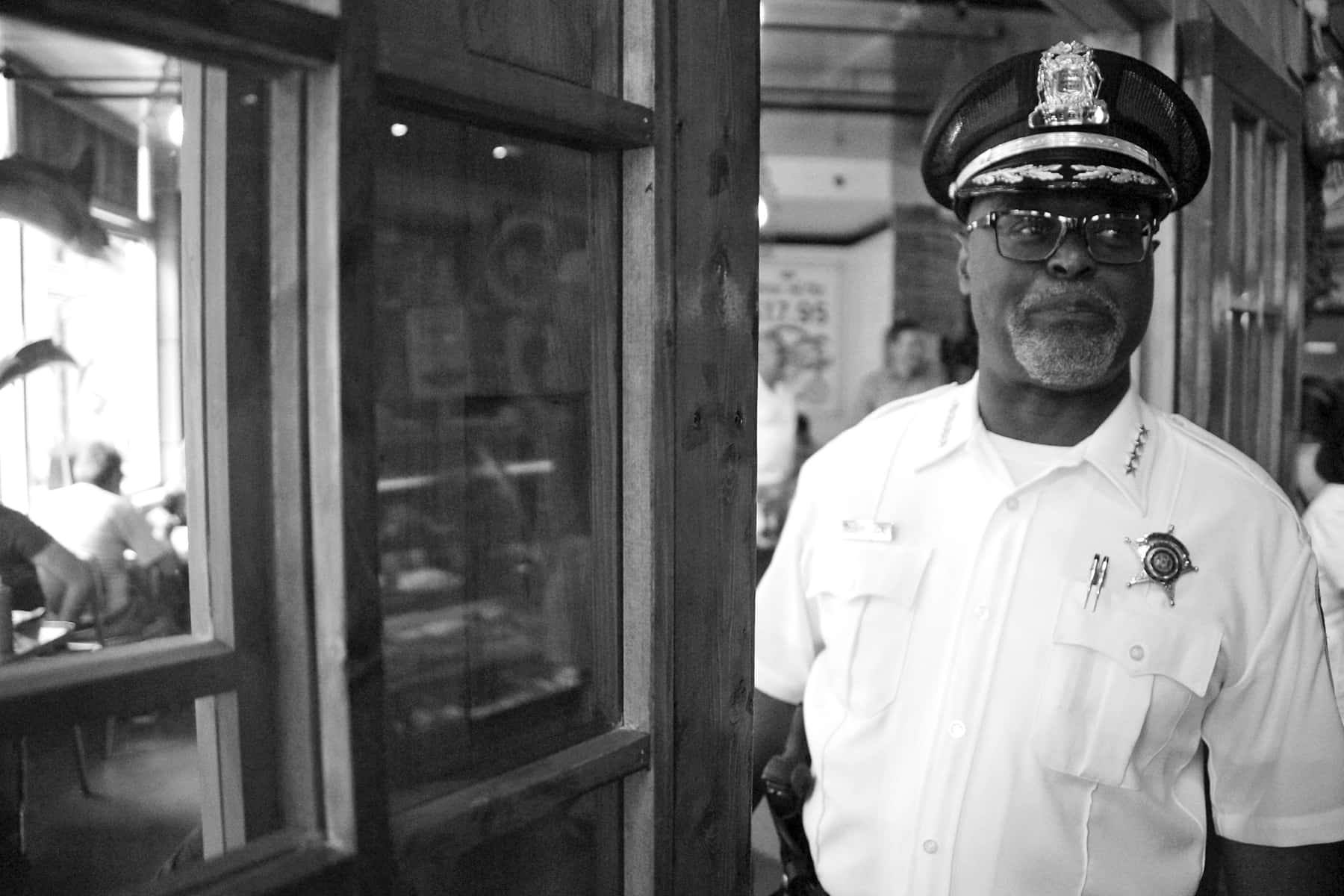

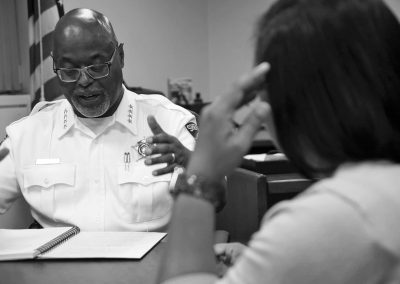

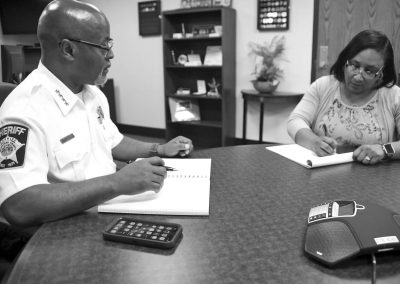

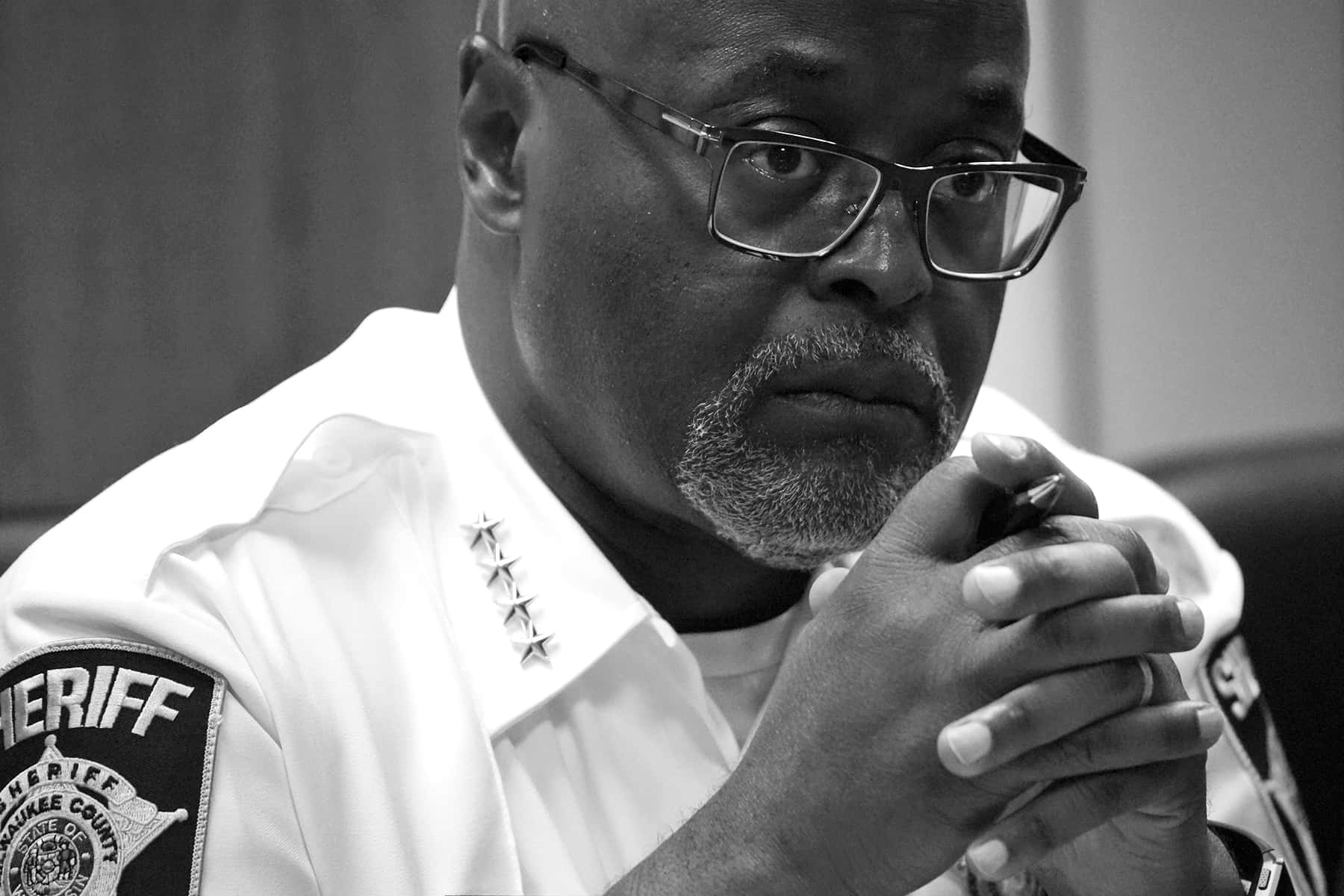

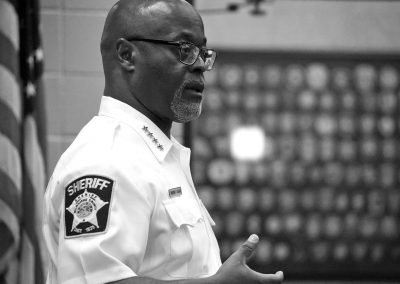

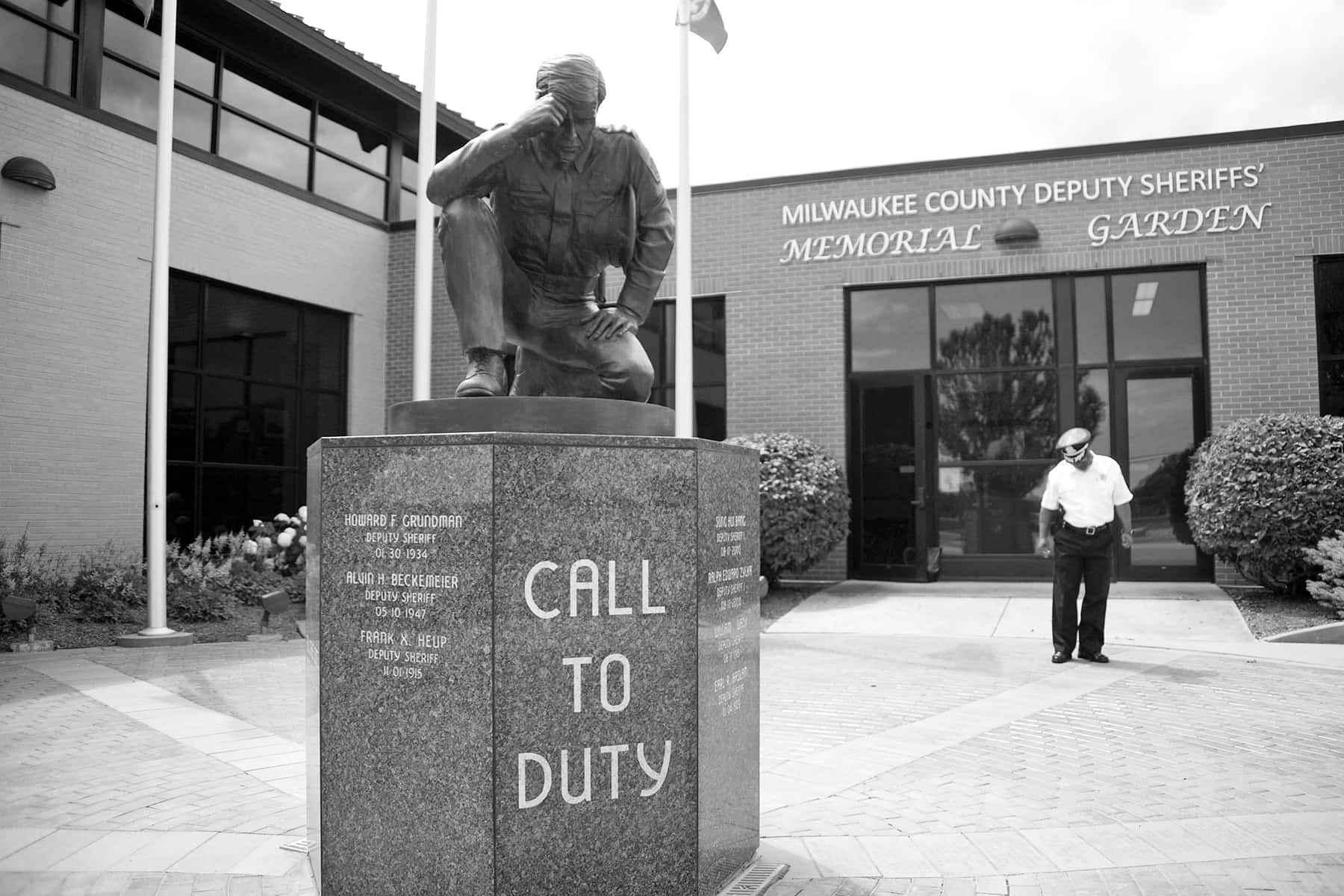

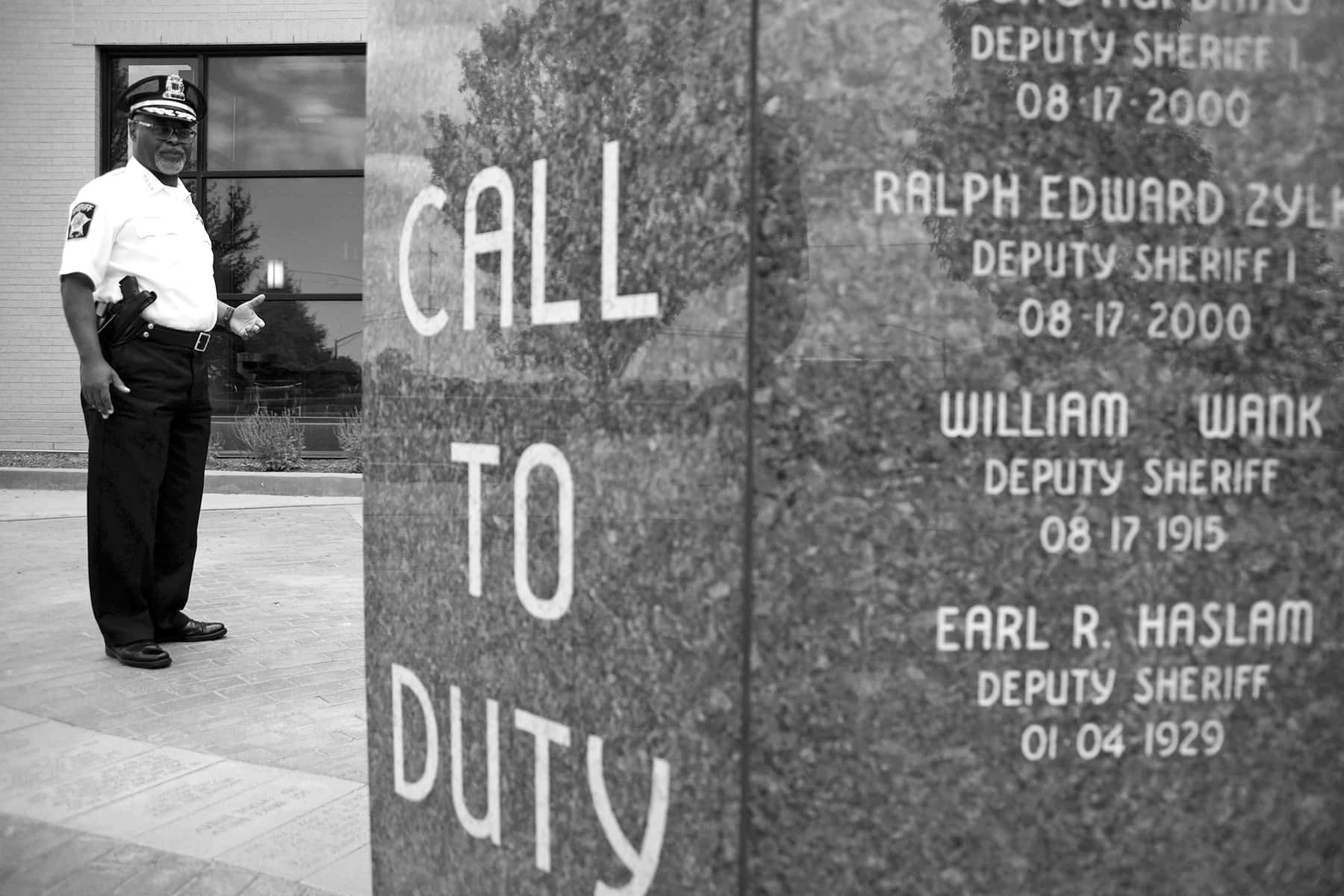

Sworn in as the newly elected Sheriff of Milwaukee County in January, Lucas inherited a history of challenges along with the role. From managing a profession that grapples with work-related trauma, to reconnecting with a vulnerable community that has had little reason to trust law enforcement, Lucas has made restoring honor, integrity, and trust to the Milwaukee County Sheriff’s Office one of his top priorities.

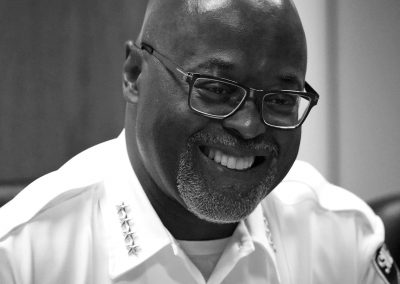

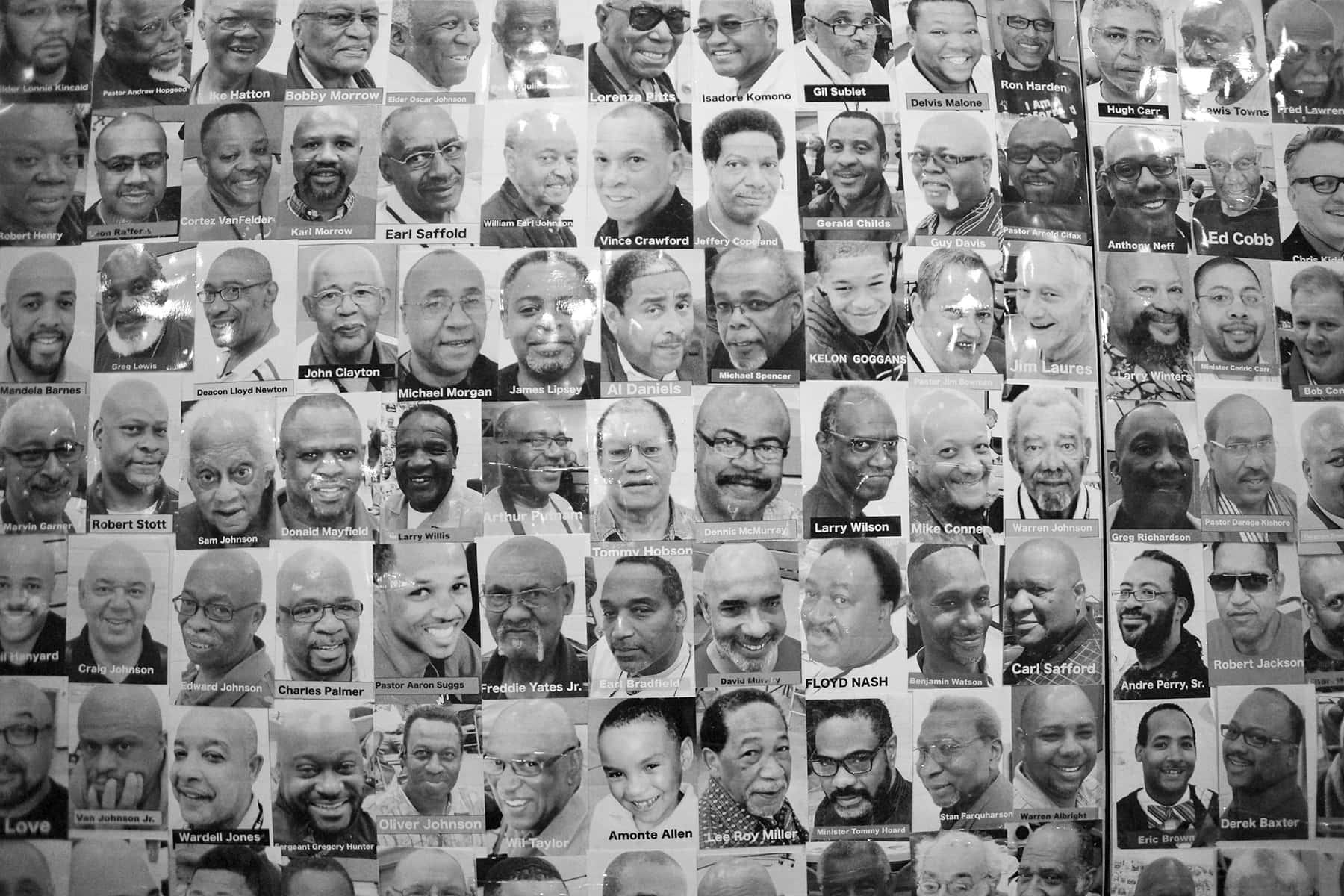

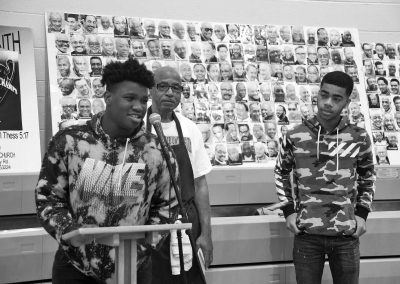

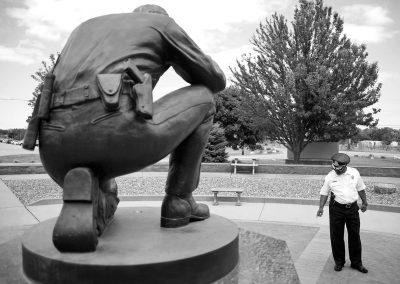

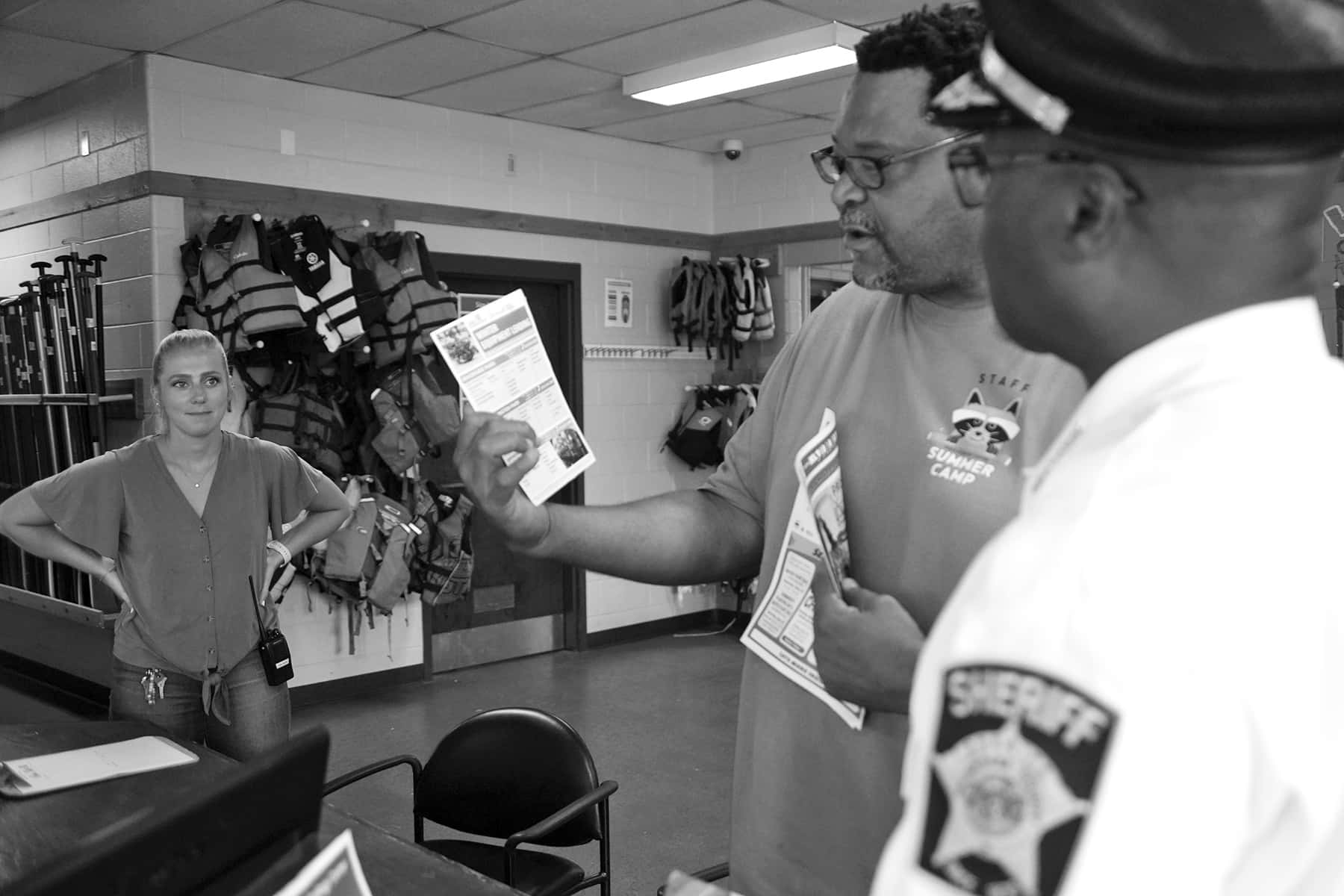

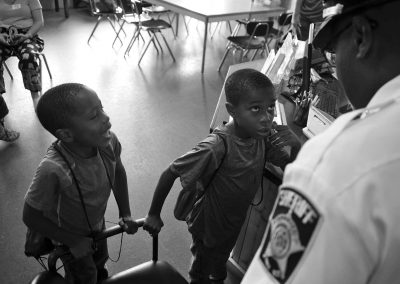

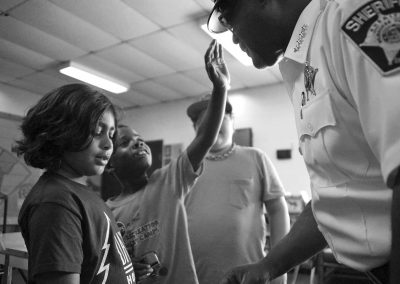

As a retired Milwaukee police captain, he is driven to serve his community and inspire its youth to reach for their dreams. After more than a half year on the job, his sincerity is earning him a reputation as the People’s Sheriff, with the will to do the right thing for helping others. Lucas sees his ongoing efforts as vital to healing broken neighborhoods and building brighter tomorrows for Milwaukee’s future generations.

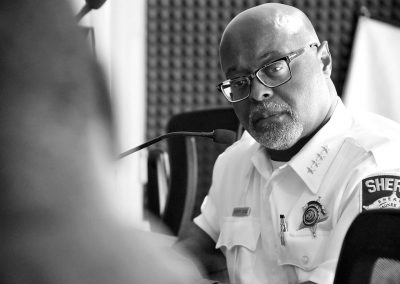

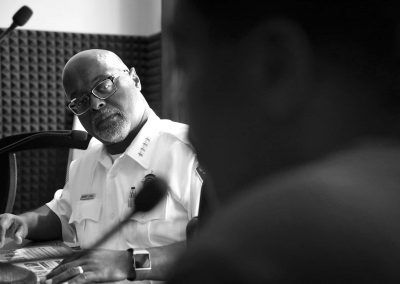

Q&A with Earnell Lucas, Milwaukee County Sheriff

Milwaukee Independent: Who had the biggest impact on your childhood, and do you still see that influence on your life today?

Earnell Lucas: That, without a doubt, would be my grandmother, Mrs. Amanda Lucas Gray, or Ms. Mandy, as many called her. She was relatively untutored but a profoundly intelligent woman. She was a domestic worker in Jasper, Alabama, a small town outside of Birmingham, who raised four children, including my mother. She gave up everything she had worked for, including the home she built and the life she was living to move to Milwaukee to raise three young boys upon the death of our mother in September 1969. She taught us values like a hard day’s work for a day’s pay and treating others the way we want to be treated. She instilled in me a desire to always want to do my best. I truly love and miss my grandmother, but her loving nature, her nurturing spirit and her profound intelligence and wisdom are still with me to this day.

Milwaukee Independent: What is the most memorable experience from your youth growing up in Milwaukee?

Earnell Lucas: When I was twelve years old, my grandmother sent me to the store with a note and a $20 bill. At the corner of 2nd and Burleigh, I was stopped by a Milwaukee police officer, who accused me of stealing a woman’s purse. The officer stated that he was going to run me over and have the woman identify me, and I responded, “That’s fine, but if the woman doesn’t identify me, you’re going to have to run me back over to the store and help me get these groceries home, or Grandma’s going to be upset.” The officer drove off without another word, and in that moment, I came to two realizations: one, that police officers are vested with immense discretion to impact others’ lives, both for good and for bad; and two, that I aspired to use that discretion for the betterment of others.

Milwaukee Independent: What role has the environment of trauma played in your life, and do you have hope that future generations will not face those conditions one day?

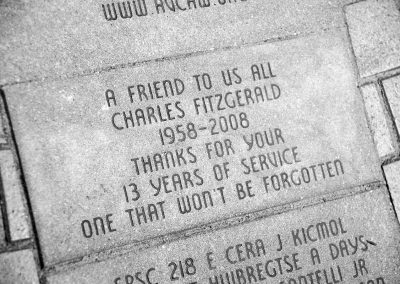

Earnell Lucas: We cannot address an epidemic if we do not acknowledge its existence. As a community, we are beginning to appreciate the pervasive role of trauma in shaping the trajectory of an individual’s life. We are beginning to understand the decades-long impact of adverse childhood experiences, and we are beginning to intervene in ways unthinkable in the 1970s and 1980s. These signs of progress give me hope that future generations will not encounter, as my generation did, a resistance to grappling with or even acknowledging traumatic experiences. On January 1, 1982, I sustained a gunshot wound to the face while responding to a call for service at 10th and Walnut. During my recovery, I received no counseling or support services, only a periodic inquiry as to when I was returning to work. Today, we have moved past that mindset. In our agency, we strive to provide our deputies and officers with the resources they require to thrive in a profession that frequently grapples with trauma.

Milwaukee Independent: What inspired your interest with a career in law enforcement, and why did you decide to stay in Milwaukee?

Earnell Lucas: From the moment I encountered that police officer at 2nd and Burleigh, I knew that I wanted to serve in the Milwaukee Police Department. I stayed in Milwaukee because everything I have achieved in my life has its roots in this community. I was born in a room in the Hillside Housing Project and I was raised at 2nd and Burleigh. I went to school at Victor Berger Elementary, Robert Fulton Junior High, Rufus King High School, and Marquette University. I raised a family and built a career here. I love this

community, and I love our people. Even when I was working in New York, Milwaukee always remained my home. To paraphrase a minister, “I was Milwaukee born and Milwaukee bred, and when they lay me in the ground, I will be Milwaukee dead.”

Milwaukee Independent: How did the injury you received as a young police officer in Milwaukee change your life, and what role did faith play in your recovery and healing?

Earnell Lucas: My injury gave my life a sense of urgency that I never experienced before. I was a young husband and father at that time. My daughter had been born just sixteen days prior, and I had a two-year-old son. When I was shot, I imagined my children growing up without a father, and I imagined their mother going on in life without a husband, and those thoughts made my will and desire to live even greater. I recall falling to my knees and asking the question, “Why?” And clear in my mind was the loss, just eight days prior, of two of my colleagues, Milwaukee Police Officers John Machajewski and Charles Mehlberg. I also recall that my father, who is a very strong and God-fearing man, said something that he very rarely uttered. When he walked into my hospital room and saw my condition, he broke down and told me that he loved me. These experiences truly affirmed my faith that there is a God in heaven above.

Milwaukee Independent: As the economic impact from lost manufacturing jobs hit the city, what was your biggest challenge as a man of color and a Milwaukee police officer in the 1980s and 1990s?

Earnell Lucas: The loss of manufacturing jobs in Milwaukee had a profound and destabilizing impact on our community. Home ownership became a significant challenge for many, and with that challenge came increased homelessness. Economic instability led to conditions – increases in poverty, crime, and imprisonment – that I found deeply challenging, both as a person who had grown up in our community and as a police officer trying to serve our community. Additionally, with the loss of manufacturing jobs, some resorted to committing acts of crime, which required a great deal of police resources and only perpetuated cycles of single-parent homes, drug dependency, and violence in our streets. These conditions made for two very challenging decades throughout our community.

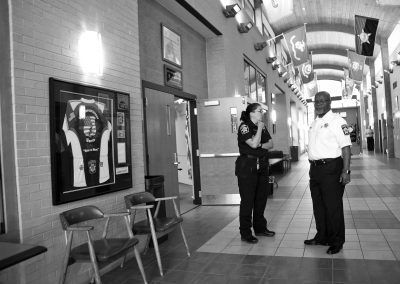

Milwaukee Independent: What are you most proud of from your career with the Milwaukee Police Department, and what were you striving for but unable to accomplish?

Earnell Lucas: When I reflect upon my career with the Milwaukee Police Department, I am confident that I lived up to my youthful aspiration: to use the broad discretion entrusted to the police for the betterment of my community. I am very proud of the work accomplished at District 3 during my tenure as captain. We helped build partnerships with residents, nonprofits and businesses that continue today in the form of the Near West Side Partnership and similar efforts. Among my greatest regrets is that, when I left and still today, police supervisors of color struggle to find gainful employment after retiring from MPD. Retired inspectors, captains, and lieutenants often secure chief positions in suburban departments, but it is rare to find a retired supervisor of color in such a position.

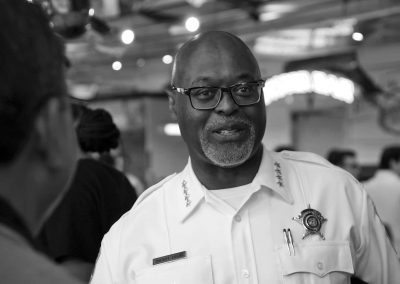

Milwaukee Independent: As the 65th Milwaukee County sheriff and 3rd African-American in that position, what role does your identity have in accomplishing your mission to heal the community and repair relations with law enforcement?

Earnell Lucas: I pursued this role to restore honor, integrity, and trust to the Milwaukee County Sheriff’s Office. It is not my intent to be the best African-American sheriff that I can be for Milwaukee County. It is my intent, always, to be the very best sheriff that I can be for Milwaukee County. I have focused my experiences, my aspirations, and my hopes on doing just that, by restoring the relationships our office has with the community we serve, and by inspiring some young boy or girl to do whatever it is that they set their sights on. I am committed to delivering the level of service that the people of Milwaukee County truly deserve – that is the hope and aspiration that I have for fulfilling my role as the 65th Sheriff of Milwaukee County.

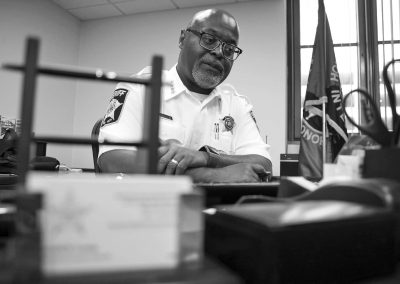

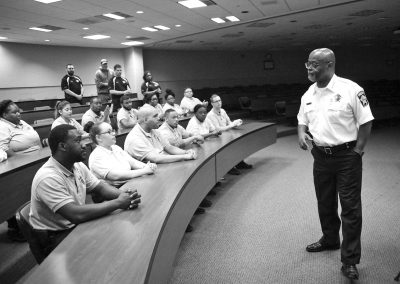

Milwaukee Independent: What do you enjoy most about your current work, and what has been the biggest unexpected challenge?

Earnell Lucas: The greatest joy of serving as a law enforcement executive is the opportunity to lead talented, hardworking, and deeply honorable public servants. The troubled history of the Milwaukee County Jail is well-known. Less well-known are the two hundred correctional officers whose tireless work, under extremely arduous conditions, is helping transform our facility into one that upholds the dignity and rights of inmates and staff. Every time I enter the jail facility, I am greeted by correctional officers who tell me that despite the long hours and low pay, they love their jobs. I have spoken with correctional officers who left higher-paying, easier, and safer jobs in the private sector to follow a calling to public service. While Milwaukee County’s financial resources are severely challenged, it is a great pleasure to lead an agency rich in human resources.

Milwaukee Independent: With a lifetime connected to Milwaukee, how have you seen the city change for the better? And, where has it not improved or gotten worse in that duration?

Earnell Lucas: As a young police officer, I patrolled neighborhoods including Milwaukee’s Upper East Side. It was always challenging to find that some residents did not want officers who looked like me to so much as enter their homes. Today, our deputies and officers are welcomed everywhere, and I live in one of those neighborhoods where, years before, I couldn’t have imagined entering a home, much less owning one. But as we make progress in certain areas, we encounter deep and systemic challenges in others. As I drive through our community, I observe a great deal of brokenness – often symbolized by empty homes and vacant lots. Years ago, strong families occupied those homes and strong neighborhoods sat astride those lots. But because of the economy, because of the loss of jobs, because of drug abuse and because of violence, brokenness has set in. As a community, we must overcome this brokenness, and I am confident that we will. Across Milwaukee County, we are witnessing community members of all ages, all races, and all backgrounds coming together to repair that which has been broken and build brighter tomorrows for future generations.

Milwaukee Independent: What is the most common question you are asked, and what does no one ever ask you about that you wish they would?

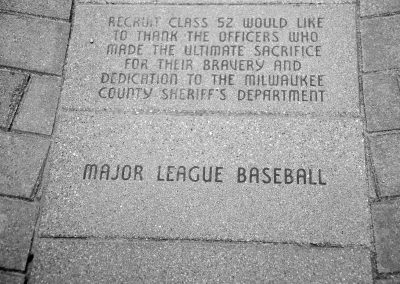

Earnell Lucas: I am often asked if I regret leaving an executive role with Major League Baseball to return to the less profitable and more perilous world of public service. I don’t. That doesn’t mean that our community lacks challenges. All too rarely – especially in county government – do we muster the perseverance to size up a challenge and ask ourselves, “What concrete actions are we going to take now, at this very minute, to get the job done?” Instead, we ask ourselves, “Where will we find the resources?” or “What aspects of the problem do we need to study?” Those are important questions, but useful only as guideposts supporting a course of action. If we allow our resource deficits and institutional woes to become synonymous with stagnation, we will be shirking our duty to the people of Milwaukee County.

Milwaukee Independent: If you could send a message back in time to yourself at age 18, what would you say?

Earnell Lucas: “Don’t expect to get if you’re not willing to give.”

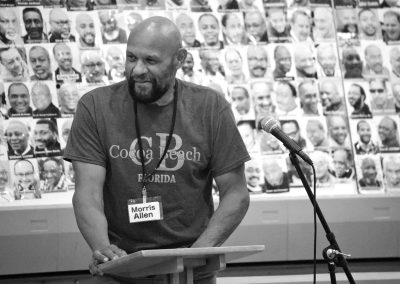

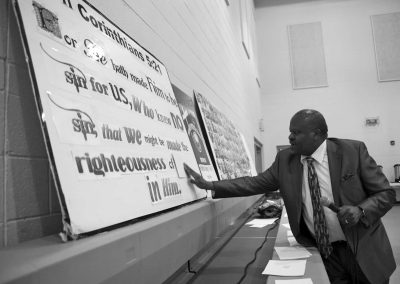

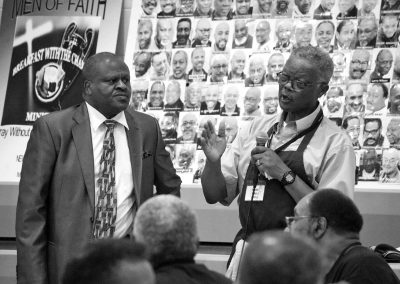

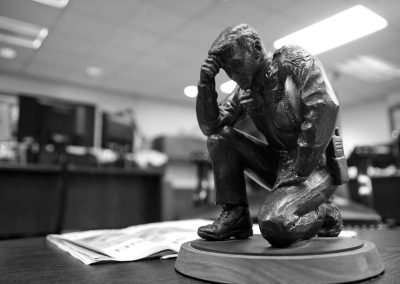

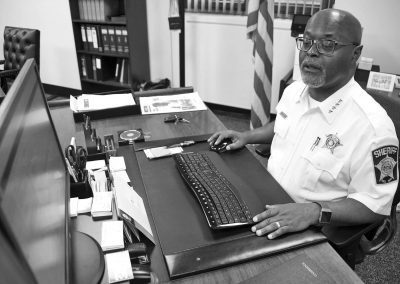

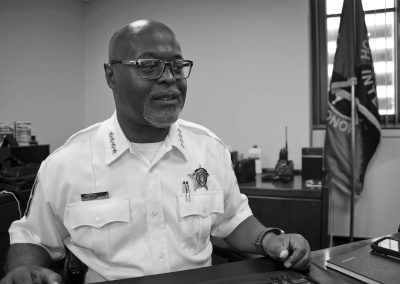

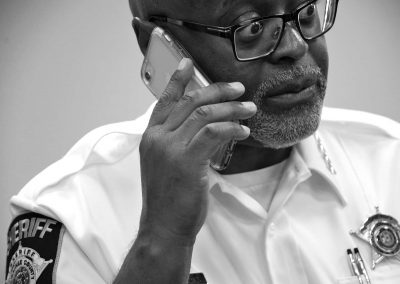

This photo essay follows the artistic style used in previous “A Day in Photos” features. Monochrome images are timeless, and express emotion far better than color photographs, which communicate information. After taking pictures at seven different locations in one day, each with its own unique lighting, it was decided to converted them to black & white in post production. By removing the color spectrum, the images were equalized so that viewers could see them as part of the same narrative regardless of where they were taken.

Lee Matz