2020 marks the 150th anniversaries both of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution confirming male African American suffrage, and of the first full United States census of African-Americans. Commemorating these consequential milestones prompts reflection about the hard fight obtaining, retaining and maintaining both ballot access and census accuracy.

The steps towards official African American citizenship and civil rights were absurdly incremental; they began decades before 1870 and were not achieved in law for nearly ten decades after 1870 – upon the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In recent years, the federal judiciary removed critical enforcement provisions of the Voting Rights Act, [1] prompting a surge of state legislation retrogressing voter rights. Other recent federal and state legislative, executive, and judicial efforts at best compromise and at worst suppress the casting of votes and the counting of all residents. The consequences of even unintentional voting hurdles are no less than altered election outcomes.

However, 2020 also marks a year when each person can add to who counts and when; each can assert citizenship and civil rights by completing a ballot and completing a census form.

In Milwaukee, the next general elections are: Spring Nonpartisan Election and Presidential Preference Primary – April 7, 2020; Partisan Primary – August 11, 2020; General and Presidential Election – November 3, 2020. For reliable voting information visit: myvote.wi.gov and vote411.org.

In Milwaukee, the next census begins with online and mailed forms in March 2020, inviting every person to be counted on April 1, 2020. [2] The count only occurs once every 10 years. It determines the number of representatives Wisconsin sends to Congress, and currently determines Milwaukee’s and Wisconsin’s allocation of $675 billion in annually-available federal funds. For reliable census information visit: milwaukee.gov/2020Census and 2020census.gov.

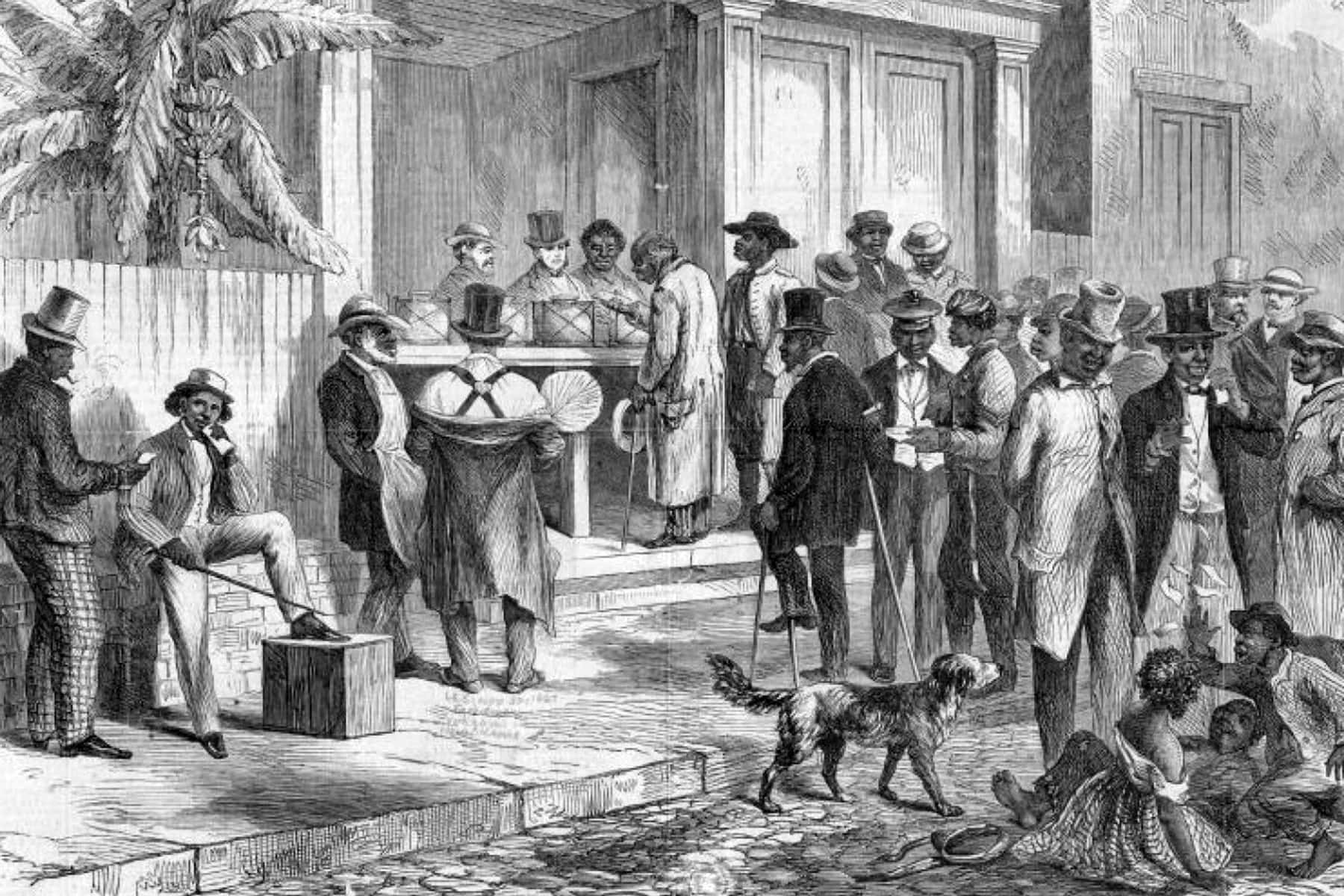

The Incremental Steps Towards Citizenship and Civil Rights: From Slave To Chattel To Citizen To Voter.

African captives and slaves were brought to the Americas beginning 400 years ago. Slaves and slavery were not addressed at all in the 1781 Articles of Confederation- the controlling governmental agreement of the loosely organized, former U.S. colonies. Essentially, the newly established states operated separately; the states without slaves had no collective interest or say in the economies or operation of slave-holding states, and vice versa.

Originally, all taxation in the states was based on land. Each of the states’ particular populations and their demographics did not matter. The Constitutional Convention members shifted to taxation based on state population. This per person change meant that the slave counts became a governmental and strategic concern among the states. Further, the Convention apportioned the allocation of Congressional representatives (and power) based on state population. The Constitutional Convention’s oppositional factions argued, and eventually adopted the nascent U.S. census’ “3/5th Compromise.”

The Constitution provided that three-fifths of a state’s slave population would count towards the state’s total population. [3] The resultant number determined representation in Congress and the allocation of each state’s otherwise disproportionate tax obligations. While the Compromise commonly and mistakenly is understood to count each slave as three-fifths of a person, the actual census counted only three of every five slaves within a state. The other U.S. Constitution reference to slaves discusses the restraint on Congress that it may not limit international slave trade before 1808 except providing for the tax or duty on “[t]he Migration or Importation of such Persons” “such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.” The clause is a tortured effort not to use the word “slave.” The clause refers to captive Africans as “Persons” when such persons were otherwise only identified as chattel. [4]

Citizenship and naturalization were limited by statute exclusively to “free white persons,” explicitly excluding both slaves and free Blacks. [5] In the five decades following the prohibition of international slave trading, [6] any reinterpretation of the citizenship and even the personhood status of African-Americans was dispelled by the 1857 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford. [7]

In the court case, an enslaved African-American unsuccessfully sued for his freedom based on his residency, where slavery was illegal. The Supreme Court decided that “none of the rights and privileges” granted to citizens by the Constitution could be so claimed by Scott. Further, the Court held that besides not being citizens, African Americans were not even persons under the Constitution. The decision fueled the free state/slave state debate, fanned north/south state tensions, and accelerated the southern state succession.

After the Civil War began, Congress passed several federal acts changing the legal status of slaves. They included the April 1862 and June 1862 legislation abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia and banning slavery in the territories, respectively; and Lincoln’s January 1863 Emancipation Proclamation freeing all the slaves in Confederate territory.

The cluster of the Thirteenth [8], Fourteenth [9] and Fifteenth Amendments [10] recognized the Constitutional transition of African-Americans from slaves to persons (the 13th – 1865-abolishing slavery), to citizens (the 14th -1868 securing civil rights), to voters (if male) (the 15th – 1870 securing secure political rights). [11]

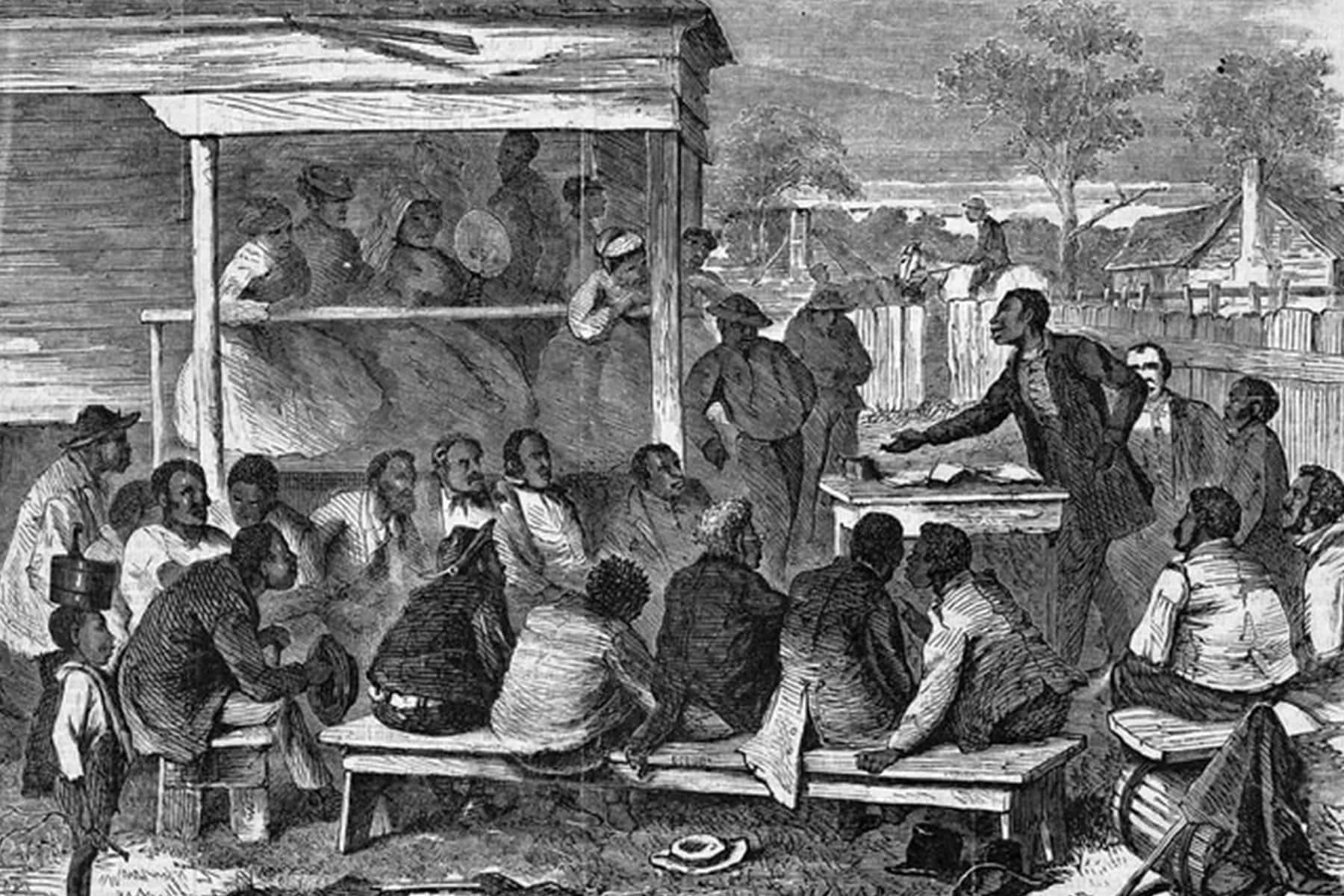

Immediately after the Civil War in 1865 and in the wake of the 13th Amendment’s ratification, Congress created the United States Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau. It operated until 1872, helping four million former slaves transition to freedom and eventually citizenship. The Bureau’s work was practical and aspirational: physically protecting freedmen and women from persistent Southern White abuses as well as providing necessities, securing military back pay and pensions, promoting education and labor systems, and settling freedmen on confiscated lands.

Post-Civil War, Congress passed many acts to expedite Reconstruction of the Confederate states, and to expand freedmen’s participation in commerce and government. For example, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and served as a statutory place-holder for the 1868 ratification of the 14th Amendment.

After the 15th Amendment provided the vote to male African-Americans, they became both electors and elected almost immediately. Indeed, in 1870 the first African-American to sit in the U.S. Congress was elected to the U.S. Senate, and during the Reconstruction Era twelve Black men served in Congress and over 600 Black men served in state legislatures. However, the 15th Amendment also provided to states the authority to institute voter qualifications. Many former Confederate states took advantage of this power — instituting poll taxes, literacy tests, and other discriminatory practices. These stated-based “qualifications” eventually paved the way for Jim Crow laws, intimidation and unchecked violence to prevent African Americans from voting. Well before the 20th century, nearly all African Americans in former Confederacy states again faced disenfranchisement.

For African Americans, especially in the South, the struggle to fully achieve 14th and 15th Amendment rights continued into the 20th century until passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It sanctioned many legal state and local barriers to the 15th Amendment’s right to vote. Until the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Black women were excluded from voting for another 95 years after ratification of the 15th Amendment. Even though the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote in 1920, Black women were disenfranchised due to race-based, discriminatory voting “qualifications.”

In 1964, the 24th Amendment banned poll taxes in federal elections, and in 1966 the U.S. Supreme Court banned poll taxes in state elections. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 gave African-American voters the legal means to challenge voting restrictions and led to a vastly improved voter turnout and voice.

The First Full Count – The 1870 Census

2020 also marks the 150th anniversary of the first time that all African-Americans were counted in the decennial census, as provided in the U.S. Constitution Article I, Section 2 and the 14th Amendment. The 1870 census included a variety of now dated designations for the populations it recorded.

The census added the categories of “Native” and “Foreign” to its previous population breakdowns of “White” and “Colored.” In 1870 Wisconsin and Milwaukee County populations totaled 1,054,070 and 89,930, respectively. The census recorded 2133 “Free Colored” persons in Wisconsin and 185 in Milwaukee County— modest increases from the 1860 census of 1171 persons and 107 persons, respectively.

Wisconsin overall ranked as the 15th most populous state of the 37 states then admitted. It ranked eleventh highest with a “White” population (New York ranked first), and thirteenth highest with a “Colored” population (Georgia ranked 1st). The only recorded “Slaves” in Wisconsin appear in the 1840 census – with ten “Slaves” in Grant County and one in Iowa County. The 1840 state census included 196 “Free Colored” persons.

The 1870 census also collected data on Education, “Pauperism” and Crime. As of mid-year 1870, 1533 Wisconsinites received public support, including 16 Blacks and 736 “Foreign Born,” with a total support amount of $151,181.00. Convicted Wisconsinites in 1870 totaled 837, including 21 Blacks and 203 “Foreign Born.” Statewide school attendees totaled 260,732, including 180 Black male students and 126 Black females.

The City of Milwaukee’s 1870 population totaled 71,440, including 175 Black persons notably concentrated in the then 4th Ward. In 1970, one hundred years after the first full African-American census, the Census Bureau estimated that over six percent of African Americans went uncounted, compared to only two percent of European Americans.

Today, the Milwaukee is a city of majority minorities; an accurate count of all residents is pending with the 2020 U.S. Census. In 2019, Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett convened the Greater Milwaukee 2020 Census Complete Count Committee stating “I want every household to participate and I want to engage as many residents as possible to make sure no one goes uncounted.”

The data collected in the “count” is actually information as of April 1, 2020, e.g., a total of household residents; household rentals or homeownership; gender, age and race of each household member, and the relationship of each person in the home.

ALL persons must be counted, regardless of age, race, ethnic group, citizenship status or immigration status. The 2020 census questionnaire does NOT include a question regarding immigration status.

The Census Bureau, operated by the U.S. Department of Commerce, is bound by federal law to keep ALL information confidential. The Bureau cannot release any identifiable information about a person, a household, or a business. The law ensures that ALL private data is protected and that no answers can be used against a respondent by any government agency, law enforcement agency, or court.

For the first time in 240 years, the U. S. Census Bureau allows online or phone options for submitting census responses – in addition to the traditional mailed option, if one prefers. As residents options for census data collection have increased over time so has its uses. The annual distribution of more than $675 billion in federal funds – over the next 10 years – is based on census data. The funds support education, housing, transportation, health services, etc. and are critical to the operations of local communities.

But the original census count purposes remain: the allocation of seats Wisconsin fills in the U.S. Congress, and the proportionate taxation of states.

Library of Congress

- [1] Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529 (2013)

- [2] U.S. Constitution, Article 1, Section 2

- [3] 1789 U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 2

- [4] U.S. Constitution, Article 1, Section 9

- [5] The Naturalization Act of 1790

- [6] U.S. Constitution, Article 1, Section 9

- [7] Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) (1857)

- [8] The 13th Amendment states: Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

- [9] The 14th Amendment states: “Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. Section 2. Representatives shall be apportioned among the several states according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each state, excluding Indians not taxed.

- [10] The 15th Amendment states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

- [11] Congress required former Confederate states to ratify the three Reconstruction Era amendments as conditions of regaining federal representation.