The Jewish Museum Milwaukee organized a bus tour through historic Milwaukee Civil Rights sites on March 11, in predominantly African American and Jewish communities like the Haymarket area and Sherman Park.

Dominic Inouye, the founder of ZIP MKE and contributing columnist with the Milwaukee Independent, led the excursion that connected a span of decades. He shared stories about local landmarks, including where Jewish synagogues had once existed.

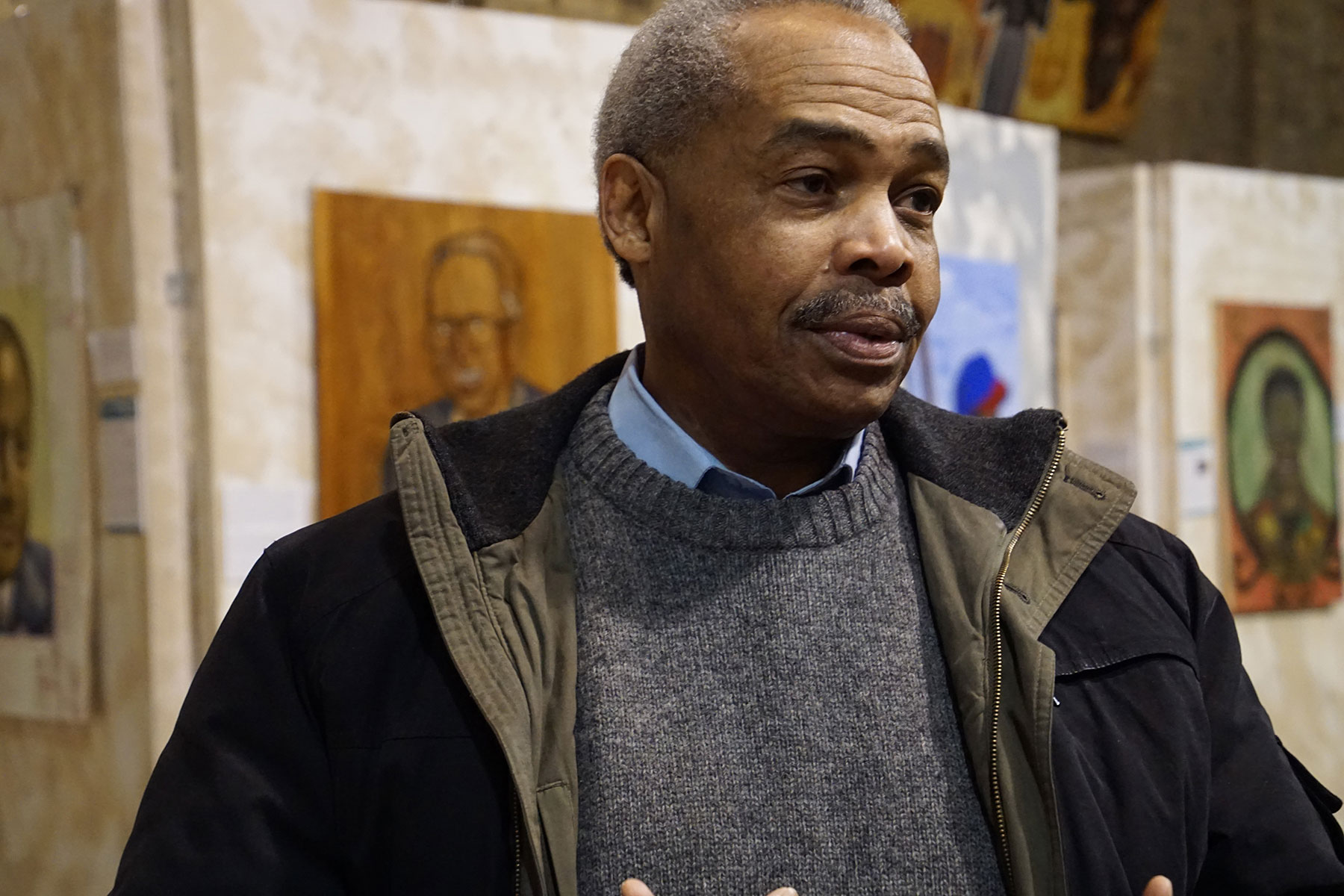

Stops included visits to the Wisconsin Black Historical Society and Museum with a talk by its foundering director Clayborn Benson III, and a session with Sheri Williams Pannell, Artistic Associate of First Stage, for an overview of the Bronzeville area.

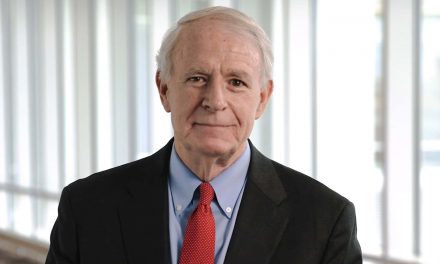

The tour came full circle when the bus followed the march route used by protesters demanding open housing fifty years ago, and crossed the James E. Groppi Unity Bridge on 16th Street. Margaret Rozga, author, emerita professor of English, Civil Rights activist, and widow of Father James Groppi shared her memories of that day, when demonstrators originally gathered at that spot on the then mostly white South Side, as part of their historic rally at Kosciuszko.

The audio segments of Sheri Williams Pannell and Margaret Rozga were recorded live during the tour, and the included photos feature the historic route designed by Inouye with corresponding map markers.

“Jews who are all together familiar with the humiliation of being unable to sleep where they want to sleep, who were quarantined in ghettos for so many years and still are in many places, Jews who were denied opportunities in all sorts of employment and still are in some places in our country, who were unable until the end of WWII to practice medicine in many hospitals and still cannot, who entered many universities on a quota system and still do, who cannot join many social clubs, including some within our own city, who have met hate and murder, can hardly be onlookers when one of the great battles for freedom goes on before their eyes.”

– Melvin S. Zaret, then executive director of Milwaukee Jewish Welfare Fund

German-Jewish immigrants settled in the Haymarket neighborhood from Walnut Street to Juneau Avenue and 8th to 3rd Streets in the 1850s. Hay was the fuel for hungry urban horses and the material supported the Schlitz brewery to the east and Pabst brewery to the west. By the 1890s the Haymarket was mainly inhabited by Russian Jews, and the area was commonly referred to as “the Jewish ghetto” and “urban slum” by 1915.

Between 1920 to 1940, Jewish residents began moving in large numbers to the new Sherman Park, with its bungalows, duplexes, lawns, setbacks, and trees. The population shift coincided with decreased Jewish immigration from Europe, and the settlement of Southern Blacks in the old neighborhood seeking higher-paying industrial jobs as they escaped from Jim Crow segregation.

The Black population in Milwaukee County quadrupled from 2,300 to 9,000, as the Milwaukee Real Estate Board steered Blacks to Haymarket because of racially restrictive covenants. Orthodox synagogues were abandoned, demolished, or converted into Christian churches.

Black residents grew from 46% to 85% of the old Jewish quarter’s population from 1940 to 1960, with a population of over 20,000 by 1950. Sherman Park’s Burleigh Street, between 43rd and 60th Streets, became known as “synagogue row” as the Jewish population moved from the Haymarket area.

But by late 1950s, Black residents also began moving to Sherman Park, and Jewish residents began moving to the outlying suburbs of Shorewood, Whitefish Bay, Glendale, and Fox Point, marking a second wave of abandoning synagogues.

“We cannot pretend that the insult to us in this country anywhere approaches the humiliation and the indignities to which the Negro is subjected. We must not pretend that we do not see the badge of inferiority placed upon the Negro. Gradually, the eternal quest for human dignity, like the Jewish struggle, is speeded up. Our history, our collective experience, our tragedies and our glories as a people dictate that we have a special stake and responsibility in all of this. In the face of oppression and brutality – let us not be silent.”

– Melvin S. Zaret

© Photo

Lee Matz