“It is impossible to create a dual personality which will be on the one hand a fighting man toward the enemy, and on the other, a craven who will accept treatment as less than a man at home.” [1]

The end of the Civil War marked a new era of racial terror and violence directed at black people in the United States that has not been adequately acknowledged or addressed in this country. Following emancipation in 1865, thousands of freed black men, women, and children were killed by white mobs, former slave owners, and members of the Confederacy who were unwilling to accept the anticipated end of slavery and racial subordination. The violent response to freedom for former slaves was followed by decades of racial terror lynchings and targeted violence designed to sustain white supremacy and racial hierarchy.

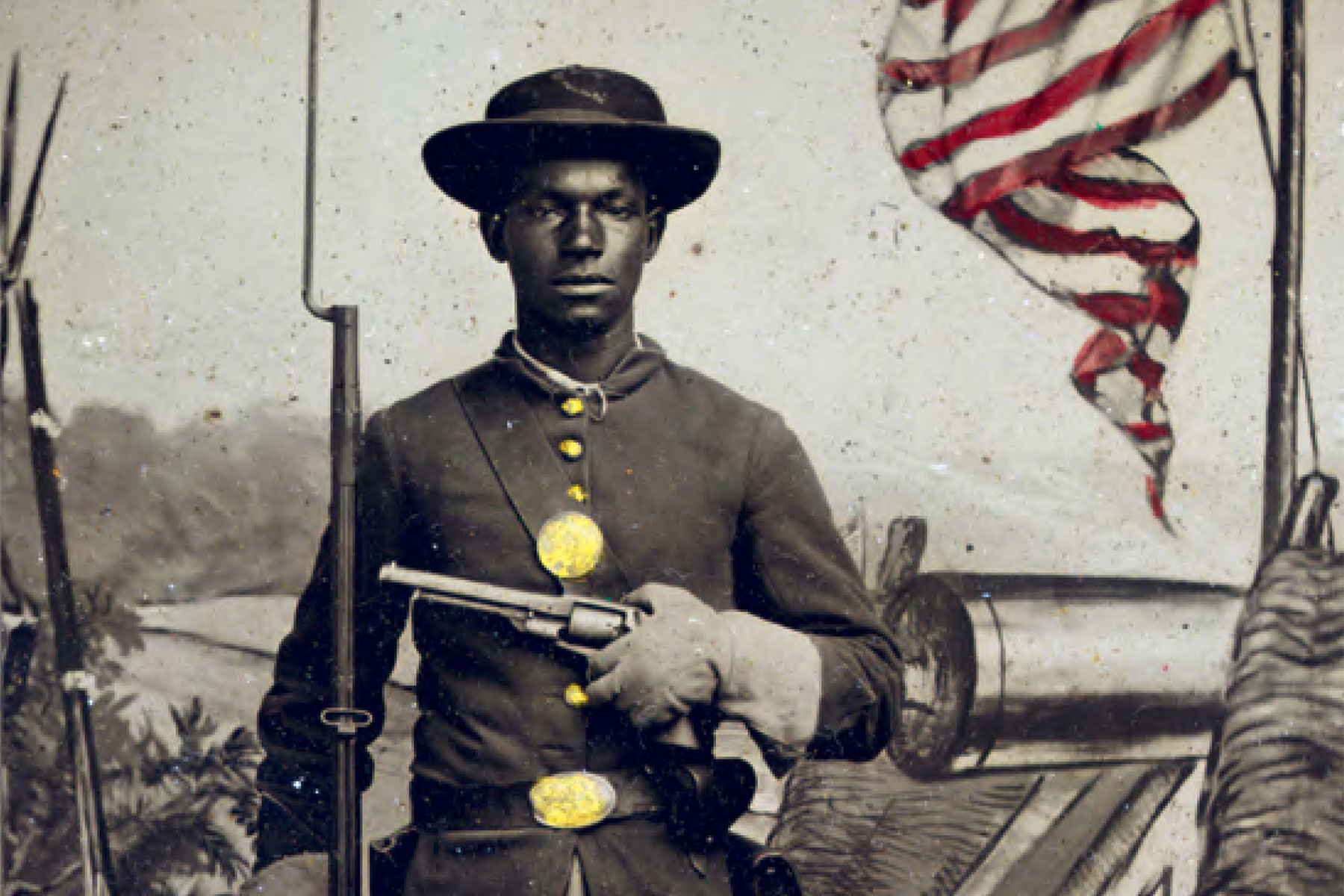

No one was more at risk of experiencing violence and targeted racial terror than black veterans who had proven their valor and courage as soldiers during the Civil War, World War I, and World War II. Because of their military service, black veterans were seen as a particular threat to Jim Crow and racial subordination. Thousands of black veterans were assaulted, threatened, abused, or lynched following military service.

The disproportionate abuse and assaults against black veterans have never been fully acknowledged. This report highlights the particular challenges endured by black veterans in the hope that our nation can better confront the legacy of this violence and terror. No community is more deserving of recognition and acknowledgment than those black men and women veterans who bravely risked their lives to defend this country’s freedom only to have their own freedom denied and threatened because of racial bigotry.

– Bryan Stevenson

Looky here, America, what you done done? Let things drift until the riots come. Now your policemen let your mobs run free. I reckon you don’t care. Nothing about me. You tell me that HitIer is a mighty bad man. I guess he took lessons from the Ku Klux Klan. You tell me Mussolini’s got an evil heart. Well, it must have been in Beaumont that he had his start. Cause everything that HitIer and Mussolini do, Negroes get the same treatment from you. You Jim Crowed me before Hitler rose to power, and you’re still Jim Crowing me right now, this very hour. Yet you say we’re fighting for democracy. Then why don’t democracy include me? I ask you this question, cause I want to know. How long I got to fight both HitIer and Jim Crow?

– Langston Hughes, Beaumont to Detroit: 1943 [2]

Introduction

From the end of the Civil War to the years following World War II, thousands of African Americans were the victims of lynchings and other forms of racial terror in the United States, often in violent and public acts of torture that traumatized black communities throughout the country. The terror and violence of the lynching era profoundly impacted race relations and shaped the geographical, social, and economic conditions of African Americans in ways that are still evident today.

Lynching and racial violence fueled the migration of millions of black people from the South into urban ghettos in the North and West during the first half of the 20th century and created a social environment in which racial subordination and segregation was maintained for decades with limited official resistance. This violence reinforced a legacy of racial inequality that has never been adequately addressed and continues to be evident in the injustice and unfairness of the administration of criminal justice in America.

Military service sparked dreams of racial equality for generations of African Americans. But most black veterans were not welcomed home and honored for their service. Instead, during the lynching era, many black veterans were targeted for mistreatment, violence, and murder because of their race and status as veterans. Indeed, black veterans risked violence simply by wearing their uniforms on American soil. [3]

The United States condoned the racial terror and Jim Crow segregation that plagued the entire black population even as it purported to fight for freedom and democracy and against fascism and racism abroad. This report is a supplement to Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror that specifically examines the history of racial violence targeting African American veterans in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Between the end of Reconstruction and the years following World War II, thousands of black veterans were accosted, assaulted, and attacked, and many were lynched. Black veterans died at the hands of mobs and persons acting under the color of official authority; many survived near-lynchings; and countless others suffered severe assaults and social humiliation. Documenting these atrocities is vital to understanding the incongruity of our country’s professed ideals of freedom and democracy while tolerating ongoing violence against people of color within our own borders. As veteran and later civil rights leader Hosea Williams said, “I had fought in World War II, and I once was captured by the German army, and I want to tell you the Germans never were as inhumane as the state troopers of Alabama.” [4]

Understanding the persecution of African American veterans is an important step toward understanding how racial violence and hatred terrorized black Americans in the century following emancipation.

The Myth of Racial Inferiority and the Black Soldier

Throughout our country’s history, African Americans have looked hopefully to military service as a way to achieve racial equality and opportunity. [5] But the dream that donning a military uniform and fighting for national honor would earn black soldiers respect and human dignity conflicted with the status black people in America had held for centuries — and often resulted in disappointment.

The enslavement of black people in the United States for more than 200 years built wealth, opportunity, and prosperity for millions of white Americans. At the same time, American slavery assigned to black people a lifelong status of bondage and servitude based on race, and created a myth of racial inferiority to justify the racial hierarchy. Under this racist belief system, whites were hard working, smart, and morally advanced, while black people were dumb, lazy, childlike, and uncivilized.

The idea that black people were naturally and permanently inferior to white people became deeply rooted in individual’s minds, state and federal laws, and national institutions. This ideology grew so strong that it survived the abolition of slavery and evolved into new systems of racial inequality and abuse. In the period from 1877 to 1950, it took the form of lynching and racial terror.

For a century after emancipation, African American servicemen and the black community at large “staked much of their claims to freedom and equality on their military service, and had cited it as a vindication of African American manhood.” [6]

Fighting for democracy was emblematic of the equality African Americans desired, and by serving their country, black veterans displayed their attachment to the nation and commitment to American values. In the face of this persistent racial hierarchy, and despite being denied full citizenship, many African Americans fought for the United States and for the aspiration that conditions would improve. [7]

Instead, black soldiers who served in the armed forces from the Civil War to World War II, during the height of racial terror and violence, faced hatred and racism even in “peace” time.

On the other side of African Americans’ hopes were whites’ fears that black veterans asserting and demanding equality would disrupt the social order built on white supremacy and the racialized economic order from which many benefitted. Many politicians feared that black veterans would believe they were equal to whites and worthy of more than poverty, poor educational opportunities, and menial labor, and would no longer be satisfied to work on farms for low wages. Southern politicians in particular feared that independent and empowered black veterans would lead other African Americans — especially in the South, where most still lived — to challenge racial segregation and subordination in bold and dangerous ways. In the minds of fearful whites, black veterans’ training in weapons and combat and their success defending the nation in battle were more a threat than a source of pride, and many voiced concerns about how those skills could be used at home. Black veterans epitomized white Southern fears of “a black population that had either forgotten or outright rejected its place in the region’s racial hierarchy.” [8]

The hopeful determination of black veterans seeking equality after military service challenged the defiant determination of white Americans to reinforce white supremacy, maintain racial inequality, and suppress black veterans’ potential as leaders and change agents. During the Civil War, white leaders viewed black soldiers as liable to use violence to destroy the social order. Throughout the lynching era, African American veterans were seen as an increasingly imminent threat to the South’s racial caste system. [9]

This tension made black servicemen targets for discrimination, mistreatment, and violence within the military and for deadly racial terror at home.

Fighting for Freedom: The Civil War and its Aftermath

When 11 Southern states seceded from the Union to form the Confederate States of America and sparked the Civil War in 1861, they made no secret of their ultimate aim: to preserve the institution of slavery. In the words of Alexander H. Stephens, vice president of the Confederacy, the ideological “cornerstone” of the new nation they sought to form was that “the negro is not equal to the white man” and “slavery and subordination to the superior race is his natural and moral condition.” [10]

Congress officially authorized the Union army to accept black soldiers on July 17, 1862. But national leaders largely considered the Civil War “a white man’s war” and the Union was reluctant to use black soldiers in combat. Northern military personnel, politicians, and President Abraham Lincoln himself expressed fear that armed black soldiers would ruin white soldiers’ morale, be harmful to the war effort, or as one Ohio Congressman warned, prove so essential that victory would weaken white supremacy. “If you make [the black man] the instrument by which your battles are fought, the means by which your victories are won,” the congressman argued in his plea against black soldiers in combat, “you must treat him as a victor is entitled to be treated, with all decent and becoming respect.” [11]

As the war dragged on and the Union incurred more casualties, [12] objections to black combat troops faded. The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which applied only to those enslaved in the Confederate states, provided that black soldiers would be accepted into all military positions. [13]

The navy gained 19,000 black sailors and 179,000 black men joined the army, making up 10 percent of its troops. Some 40,000 were killed fighting for the United States. [14]

Black Union soldiers included men who had been free in the North before the war, black men who had lived free in the South in the midst of slavery, and some who escaped slavery after the war began and joined the fight in hopes of guaranteeing their freedom and winning that of others. But acceptance into the military did not mean equal treatment. As the war against the Confederacy raged, black soldiers also had to fight for equal pay and rations that the War Department promised during recruitment. A black soldier from Pennsylvania reported that his unit was overcome with despair upon learning they would be paid less than white soldiers, and many protested by refusing to accept any payment. Despite protests and pleas from leaders including Frederick Douglass, Congress refused to pass legislation equalizing black and white soldiers’ pay until 1864. [15]

Black participation was far less common, more complicated, and more staunchly resisted on the other side of the conflict. The Confederacy was based on a belief in white supremacy and black inferiority and a commitment to continue slavery. The Confederate army refused to enlist or arm black soldiers even as the turning tide of the war led some Confederates to urge that enslaved black people should be ordered to fight just as they were ordered to work. Some enslaved black men were taken to the battlefield as servants for Confederate officers, but formal black enlistment in the Confederate army was prohibited until a desperate and largely inconsequential act of the Confederate Congress authorized black Confederate military service on March 13, 1865, just weeks before the Confederacy surrendered. As historian Leon Litwack wrote:

Few slaves were ever enlisted [in the Confederate Army], and none of them apparently had the opportunity to fight. Had the Confederacy managed to raise a black army, it would seem unlikely, particularly after 1863, that it could have fought with the same sense of commitment and self-pride that propelled the black troops in the Union Army. When he first heard of the act to recruit blacks for the Confederate Army, a Virginia freedman recalled, he had suddenly found himself unable to restrain his emotions. “They asked me if I would fight for my country. I said, ‘I have no country.’” [16]

The Civil War ended with the Confederacy’s surrender in the spring of 1865. The formal, nationwide end of slavery came in December 1865 with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which prohibits slavery “except as punishment for crime.” The legal instruments that ended racialized chattel slavery in America nonetheless did nothing to address the myth of racial hierarchy that sustained slavery. Black people were free under the law, but that did not mean whites recognized them as fully human. Nationwide but particularly in the South, white identity was grounded in the belief that whites are inherently superior to African Americans.

After the war, whites reacted violently to the notion that they would now have to treat their former human property as equals and pay for their labor. In numerous recorded incidents, plantation owners attacked black people simply for claiming their freedom. [17] Many surviving black veterans returned to the South, where they had lived — many in the status of slave — before the war. Carrying hopes of starting farms and finding loved ones lost for years or even decades, these veterans frequently faced grave danger from violent attacks and racist laws designed to restore the racial hierarchy. The success of African Americans as trained soldiers challenged the idea that black people were fit only for servitude and undermined a central tenet of white supremacy. With their military training, black soldiers “represented both a viable alternative source of community leadership and a direct physical threat to white supremacy when they came home.” [18] After a brief period, the victorious federal government gave up on Reconstruction and withdrew from the South in 1877, abandoning its duty to protect newly freed black people and enforce the citizenship rights they now held. Exploitative systems of convict leasing and sharecropping impeded economic progress and returned many black people to a status very similar to slavery. President Andrew Johnson took office following President Lincoln’s assassination and adopted policies that opposed black voting rights, restored Confederates’ citizenship, and allowed Southern former rebels to reestablish white supremacy and dominate black people with impunity. [19]

The Fourteenth Amendment, which was ratified in 1868, established that all persons born in the United States, regardless of race, are full citizens of the United States and the of the states in which they reside, and are entitled to the “privileges and immunities” of citizenship, including due process. Though a hopeful development, the Supreme Court quickly dismantled the amendment’s promise in The Slaughterhouse Cases and U.S. v. Cruikshank. [20] As a result, African Americans accused of violating the racial order were met with violence and terror; they received little protection from local officials, and they had no claim to federal assistance.

Black veterans were seen as a particularly strong threat to racial hierarchy and were an early target of discriminatory state laws. To eliminate black gun ownership, which had reached unprecedented levels during the war due to black military service, states including Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi passed laws that made it a crime for an African American to possess a firearm. [21]

Florida’s Black Code of 1866 prohibited black people from possessing “any Bowie-knife, dirk, sword, firearms or ammunition of any kind” and made violations punishable by public whipping. [22] Mississippi’s statute declared “that no freedman, free negro or mulatto, not in the military service of the United States government, and not licensed so to do by the board of police of his or her country, shall keep or carry fire-arms of any kind, or any ammunition, dirk or bowie knife.” Whites were free to own and carry firearms, but law enforcement officials were stationed at train stations to seize black veterans’ guns when they arrived; veterans who did not comply were beaten and some were even shot by police. [23]

Southern newspapers fueled whites’ fears of black veterans by publishing sensational accounts of so-called “race wars”: conflicts between supposedly innocent white police and drunk and armed former black soldiers intent on starting trouble. In May 1866, after whites attacked the black community in Memphis in what became known as the Memphis Massacre, the white-owned Memphis Argus published an editorial blaming the massacre on black gun ownership. The editorial board wrote:

Again the irrepressible conflict of races has broken out in our midst, and again our streets are stained with blood. And this time, there can be no mistake about it; the whole blame of this most tragical [sic] and bloody riot lies, as usual, with the poor, ignorant, deluded blacks…. [W]e cannot suffer the occasion to pass without again calling the attention of the authorities to the indispensable necessity of disarming these poor creatures, who have so often shown themselves utterly unfit to be trusted with firearms. On this occasion the facts all go to show that but for this much-abused privilege accorded to them by misguided and misjudging friends, there would have been no riot… The universal questions asked on all corners of the streets is, “Why are not the negroes disarmed?” [24]

The violence in Memphis is now widely acknowledged as a racially-motivated massacre. Dozens of black people were raped, injured, or killed, and many black homes, churches, and schools were destroyed by fire. The two white casualties were killed by white rioters. [25]

As the white Southern press decried their access to weapons and state legislatures strived to disarm them, black veterans were in dire need of protection. [26] In 1868, the Secretary of War reported to Congress that black soldiers in Kentucky, “[h]aving served in the Union Army, were the special objects of persecution, and in hundreds of instances have been driven from their homes.”[27] Peter Branford, a United States Colored Troops veteran, was shot and killed “without cause or provocation” in Mercer County, Kentucky, while numerous other veterans were threatened, beaten, and whipped merely for attempting to locate their families and rebuild their lives after the war. [28] At Bardstown in Nelson County, Kentucky, a mob brutally lynched a United States Colored Troops veteran. The mob stripped him of his clothes, beat him, and then cut off his sexual organs. He was then forced to run half a mile to a bridge outside of town, where he was shot and killed. The terror inflicted upon black veterans by Southern whites served to perpetuate the racial caste system and maintain power in the hands of whites after the defeat of the Confederacy. [29]

Learn More: Houston Riot of 1917

Construction on Camp Logan, a military base in Harris County, Texas, began shortly after the United States declared war on Germany in 1917. The all-black Third Battalion of the 24th United States Infantry Regiment, along with seven white officers, were deployed from Columbus, New Mexico, to guard the construction site. Soon after the black soldiers arrived on August 23, 1917, two Houston police officers raided the home of an African American woman, physically assaulting her and dragging the partially clad woman into the street in front of her five small children. A black soldier named Alonso Edwards intervened on the woman’s behalf, and police beat and arrested him.

Corporal Charles Baltimore went to the police station to inquire about Mr. Edwards’s arrest and about the police beating of another black soldier. The corporal was beaten, shot, and arrested for challenging police authority, but later released. Seemingly under attack by local white authorities, 156 black soldiers of the Third Battalion armed themselves and left for Houston to confront the police about the persistent violence.

Just outside the city, the soldiers encountered a mob of armed white men who had heard reports of a mutiny. In the ensuing violence, four soldiers, four policemen, and 12 civilians were killed. Afterward, many of the black soldiers were court-martialed and convicted. Forty men received life sentences, and 19 were executed.

Newspapers at the time reported that the soldiers had mutinied and attacked innocent white civilians. But an NAACP investigation concluded that the soldiers acted in response to ongoing police brutality. The soldiers initially intended to stage a peaceful march to the police station, but violence broke out when they were confronted by the mob of white citizens on their way to Houston. [28] No white civilian was ever brought to trial for involvement in the violence.

Mistreatment of black soldiers and veterans was not restricted to the South. Johnson C. Whittaker, who was born into slavery in South Carolina in 1858, was appointed to the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York, in 1876 as one of the first black cadets in the academy’s history. On April 6, 1880, Mr. Whittaker was found unconscious and bloody on the floor of his dorm, wearing only his underwear. His legs had been bound together and tied to his bed, and his arms were tied tightly together at the wrists. He recounted that three masked white men had jumped on him while he slept, tied him up, choked him, struck him in the head, bloodied his nose, broken a mirror on his forehead, and cut his ear lobes while saying, “Let’s mark him like they do hogs down South.” [30] Two days before the attack, Mr. Whittaker had received an anonymous note reading, “You will be fixed. Better keep awake.” Rather than condemn the attack, West Point administrators claimed Mr. Whittaker had staged it himself and court-martialed him. The prosecutor relied on notions of black inferiority and argued, “Negroes are noted for their ability to sham and feign.” [31] Mr. Whitaker was convicted and expelled from West Point.

That same decade, a mob of 50 whites from Sun River, Montana, lynched Robert Robinson, a black soldier stationed nearby at Fort Shaw. [32] Mr. Robinson was a member of the 25th Infantry, an all-black unit that had been transferred to Montana from South Dakota just weeks earlier. Mr. Robinson had been arrested for allegedly shooting and killing a man. Before he could be tried, masked men entered the jail, demanded the key, took Mr. Robinson from his cell, and brought him to the alley behind Stone’s Store, where a mob lynched him and left his body hanging over the alleyway. [33]

During the lynching era, white mobs regularly lynched black people with total impunity, facing no consequences for committing murder even when the victim was an active duty American serviceman. Black soldiers stationed in unfamiliar and predominately white areas were especially at risk of being presumed dangerous and guilty, accused of a social transgression or crime, and lynched without an investigation or trial.

On August 19, 1898, Private James Neely of the 25th Infantry — an all-black regiment that had just returned from heralded service in Cuba during the Spanish-American War — visited the small town of Hampton, Georgia, on a day pass from his post at Fort Hobson. Newspapers reported that Private Neely came into Hampton wearing his blue uniform and bayonet at his side; yet when he entered the local drug store and ordered a soda at the counter, the white owner told him black customers had to order and drink outside in the rear. Private Neely protested, the two men argued, and Private Neely was thrown out of the store and onto the street outside, where the conflict attracted attention. As Private Neely continued to insist that he had rights as an American and a soldier, a crowd of armed white men gathered and chased him down the road, firing their weapons. Private Neely was later found dead of gunshot wounds. A local coroner’s jury promptly declared that the murder had been committed by unknown parties. According to the Atlanta Constitution, army officials did not immediately respond or make arrangements to retrieve Private Neely’s remains. [34]

Some lynchings of veterans during this era were public spectacle events — brutal displays of violence attended by hundreds or thousands of white men, women, and children.

After serving at Fort Huachuca, Arizona Territory, Spanish-American War veteran Fred Alexander returned home to Leavenworth, Kansas, where, on January 15, 1901, a mob burned him at the stake. Two months earlier, the murdered body of a 19-year-old white woman named Pearl Forbes had been found in a Leavenworth ravine, stoking local whites’ outrage over recent unsupported rumors about black men raping white women. Though local police’s working assumption was that Ms. Forbes was killed during a robbery gone awry, and a medical examination showed that Ms. Forbes had not been sexually assaulted, a coroner’s jury declared without any basis that she had been strangled “for the purpose of rape.” Local newspapers fanned the flames by running sensational reports that a predator had stalked Ms. Forbes, “forced her down into the ravine, outraged her, and then killed her.” [35]

As fears of black sexual predators reached a fever’s pitch, Fred Alexander was accused of assaulting a different white woman, and before that allegation could be investigated, the authorities charged him with the murder of Pearl Forbes. For several days, a mob of thousands stalked Mr. Alexander as he was transferred from jail to jail. Mr. Alexander refused to confess to murder, but the local press — seemingly determined to fuel the mob’s rage — nonetheless printed unsupported claims that the police had learned during their questioning of Mr. Alexander that a group of black men had choked Ms. Forbes, carried her to a shanty, and taken turns raping her. [36]

A vigilante committee soon decided to lynch Mr. Alexander. Local officials cooperated with the lynch mob and posted official announcements of the lynching all over the city. When the scheduled time arrived, the mob broke into the jail and attacked Mr. Alexander with a hatchet before dragging him from his cell. In the gruesome lynching that followed, participants mutilated Mr. Alexander; castrated him, likely while he was still alive; and took parts of his body as souvenirs. The mob took the dying man to the ravine, chained him to an iron stake, doused him with some 22 gallons of kerosene or oil, and set him on fire before a crowd of thousands. [37]

Whites terrorized and traumatized black veterans during the first decades of the era of racial terror in order to maintain the system of racial insubordination that existed during slavery and to carry that deadly ideology into the 20th century.

Learn More: The Legal Lynching of Sergeant Edgar Caldwell

Beginning in the 1920s, racial terror lynchings became increasingly disfavored because of the “bad press” and negative attention they attracted to Southern communities and officials. In response, Southern legislatures pursued capital punishment as a “lawful” alternative to lynching, using rushed and biased trials, court-imposed death sentences, and formal executions to shield officials from criticism while still achieving the same ends. [38] Black veterans were often the victims of “legal lynchings” during this era, and one such case involved Sergeant Edgar Caldwell.

In 1918, Sergeant Caldwell was a decorated member of the United States Army’s 24th Infantry Regiment, stationed at Camp McClellan near Anniston, Alabama. On Friday, December 13, 1918, he boarded an Anniston streetcar. The white conductor became angry when the black soldier sat in the white section of the car, and accused Sergeant Caldwell of not paying his fare. Sergeant Caldwell insisted he had paid and the two men argued. The conductor tried to throw Sergeant Caldwell off the car, but he resisted and they struggled. The conductor called the motorman to help him, and both white men punched Sergeant Caldwell and threw him to the ground, then continued beating and kicking him. Sergeant Caldwell drew his revolver and fired, killing one of the white men and seriously wounding the other.

Military authorities arrived at the scene but, contrary to protocol, they surrendered Sergeant Caldwell to local police rather than detain him for a military investigation. Local white residents and officials were outraged that a black soldier would dare pull a gun on white men. Sergeant Caldwell was tried, convicted of murder, and sentenced to death by hanging just five days after the shooting. Every juror was white. [39] Anniston’s black community successfully urged the national NAACP to appeal the case, but the Alabama Supreme Court affirmed Sergeant Caldwell’s conviction and death sentence in July 1919. [40] The United States Supreme Court heard the case, and a national publicity campaign about the proceedings attracted support and donations from black servicemen across the country. [41] The Court ultimately rejected the appeal. Sergeant Caldwell was hanged before a crowd of 2500 spectators on July 30, 1920, in the yard of the Calhoun County jail. [42]

Red Summer: Black Soldiers Return from World War I

In the years leading up to World War I, African Americans were nearly 50 years out of bondage but in the depths of the lynching era. In 1910, approximately 90 percent of black Americans still lived in the South, where they faced the daily threat of injury and death at a white person’s whim and were deprived of the security and enjoyment of full citizenship. As a result, African Americans were divided about whether to support the war effort. The national rhetoric declared that America was joining the war to make the world safe for democracy, but for black Americans who were being terrorized and denied their constitutional rights, that battle cry rang hollow.

Among African American leaders, views were split. Influential activist and labor organizer A. Philip Randolph was not optimistic that participating in the war effort would improve the lives of black people. African Americans had sacrificed their lives in every American war since the Revolution, he reasoned, and they had yet to receive full citizenship. [43] In contrast, W.E.B. Du Bois, a black sociologist and founding member of the NAACP, advised the black community that “while the war lasts, [African Americans should] forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our white fellow citizens and allied nations that are fighting for democracy.” [44] Some 380,000 African Americans heeded Dr. Du Bois’s advice and joined the armed forces during World War I. [45]

Black servicemen were established members of the American military by this time, but few held leadership or combat positions. The majority of black soldiers were assigned to labor and stevedore battalions that built bridges and roads and dug trenches behind the front lines. This work was essential to the war effort, but white officials’s conscious effort to confine them to a lesser status within the military increasingly frustrated black servicemen. [46]

Due to prejudice and racism, the armed forces remained largely opposed to placing black soldiers in combat. While 200,000 black soldiers were sent to Europe during World War I, only about 42,000 saw battle. [47] As one historian observed, black soldiers “anxiously awaited the chance to demonstrate their valor on the battlefields… and to win the democracy they had so longingly strived for.” [48] Many black soldiers who were given the chance to fight did so heroically. Their bravery was widely celebrated by African Americans at home, and for a moment, by the entire nation.

The 92nd and 93rd divisions, both deployed to France, were the only African American divisions in the segregated United States Army to see combat during World War I. The 369th Infantry Regiment of the 93rd Division, a group of black national guardsmen from Harlem, New York, became the best known regiment of black soldiers to fight during the war. Famous for their military band and their tenacity on the battlefield, the 369th were hailed as the Harlem Hellfighters, the Black Rattlers, and the Men of Bronze. [49]

On May 13, 1918, two privates with the 369th, Needham Roberts and Henry Johnson (left), were part of an isolated five-man patrol tasked with protecting against German ambushes. At 2:30 a.m., the rest of the patrol was asleep when Private Roberts alerted Private Johnson that he had heard suspicious noises, which turned out to be the snapping of wire cutters. The two privates sent up a warning flare just as a raiding party of 24 German soldiers attacked. Private Roberts was seriously wounded during the initial assault but continued to supply Private Johnson with grenades, which he heaved at the Germans. Private Johnson was shot several times, but when his gun jammed as the Germans descended into the trench, he fought them off with his hands and the butt of his rifle, killing two and preventing them from taking Private Roberts prisoner. The German forces retreated, leaving Privates Johnson and Roberts alive, four Germans dead, and at least a dozen more wounded. [50] Private Johnson survived 21 wounds and was promoted to sergeant, and “The Battle of Henry Johnson” hit the front pages of newspapers across the United States. [51]

The French awarded Henry Johnson the Croix de Guerre avec Palme, France’s highest award for valor. In a May 1918 memo, General John Pershing, commander of United States forces during World War I, called Private Johnson’s actions “a notable instance of bravery” and agreed that he deserved credit. [52]

Black soldiers in the 92nd division had a very different experience, because of the “significant divide between French and American usage of black combatants.” Unlike the 93rd, which was assigned to fight with French troops, the 92nd was attached to the United States Army, which tolerated hostility towards black troopers and vehemently opposed placing them in combat. [53]

Learn More: Red Summer of 1919

African American veterans returned home from World War I eager to continue the fight for freedom at home. Many black soldiers returned from the war with a newfound determination to bring freedom to their own shores. As W.E.B. Du Bois proclaimed in his 1919 Crisis editorial, Returning Soldiers, “We return. We return from fighting. We return fighting. [54] Before World War I, the NAACP had just 9000 members nationwide and only 300 in the South, but by the early 1920s, national membership had risen to 100,000, with Southern chapters constituting a slight majority. [55] African Americans had returned home from the war with new and contagious confidence and assertiveness.

Red Summer refers to a series of approximately 25 “anti-black riots” that erupted in major cities throughout the nation in 1919, including Houston, Texas; East St. Louis and Chicago, Illinois; Washington, D.C.; Omaha, Nebraska; Elaine, Arkansas; Tulsa, Oklahoma; and Charleston, South Carolina. [56] In Elaine, Arkansas, whites attacked a meeting of black sharecroppers who were organizing to demand fairer treatment in the cotton market. After a white person was shot, federal troops were called in to “quell” the violence, but instead they joined white mobs in hunting black residents for several days. More than 200 black men, women, and children were killed. [57] Many African American soldiers returning from World War I were outspoken against racial discrimination, inequality, and violence that continued to plague black communities, and they played an active role in defending their communities during Red Summer. “By the God of Heaven,” W.E.B. Du Bois said of returning veterans, “we are cowards and jackasses if now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.” [58] Black veterans stood “on the front lines” as they “defended themselves from the white onslaught,” while those with light complexions reportedly infiltrated the white mobs to gather intelligence. The Washington Bee reported that those fighting back against the mobs included black veterans “who had served with distinction in France, some of whom had been wounded fighting to make the world safe for democracy.” [59] After World War I, an estimated 100,000 black veterans moved North, where they still encountered segregation, racism, and inequality. One of the first victims of Red Summer violence in Washington, D.C., was a 22-year-old black veteran named Randall Neal. In Chicago, the “presence and inspiration of black veterans, particularly those of the 370th Infantry Regiment” was critical to black Chicagoans forced to “defend themselves from white aggression.” [60] In the fall of 1919, Dr. George Edmund Haynes completed a report on the causes and scope of Red Summer. He reported that “the persistence of unpunished lynching” contributed to the mob mentality among white men and fueled a new commitment to self-defense among black men who had been emboldened by war service. “In such a state of public mind,” Dr. Haynes wrote, “a trivial incident can precipitate a riot.” [61]

Black servicemen during World War I challenged racial tropes about black men by fighting with courage and pride in the face of virulently racist attitudes and hostile treatment. Nevertheless, “[i]f African Americans learned a lesson from the experiences of black combatants and noncombatants, it was to never again underestimate the depths of racial bigotry and its ability to pervert the ideals the nation supposedly fought for.” [62]

Returning African American veterans were met with a familiar “tenacious and violent white supremacy,” [63] and their status as veterans made them special targets for white aggression. Though hailed as a hero during the war, Sergeant Henry Johnson was almost completely disabled from his wounds. Subject to the racially discriminatory administration of veterans’ benefits, he and many other black veterans were denied medical care and other assistance. After he publicly objected to the mistreatment of black veterans, Sergeant Johnson was discharged with no disability pay and left to poverty and alcoholism. Henry Johnson, patriot and war hero, died penniless and alone in 1929 at just 32 years old. [64]

In Congress, the fear that returning soldiers posed a threat to racial hierarchy in the South was a matter of public record. On August 16, 1917, Senator James K. Vardaman of Mississippi, speaking on the Senate floor, warned that the reintroduction of black servicemen to the South would “inevitably lead to disaster.” For Senator Vardaman and others like him, black soldiers’ patriotism was a threat, not a virtue. “Impress the negro with the fact that he is defending the flag, inflate his untutored soul with military airs, teach him that it is his duty to keep the emblem of the Nation flying triumphantly in the air,” and, the senator cautioned, “it is but a short step to the conclusion that his political rights must be respected.” [65]

White Americans also feared that meeting black veterans’ demands for respect would lead to post-war economic demands for better working conditions and higher wages and would encourage other African Americans to resist Jim Crow segregation and racially oppressive social customs. Veterans’ experience with firearms and combat exacerbated fears of outright rebellion. In addition, the prevalent stereotype of black men as chronic rapists of white women — frequently used to justify lynchings — was amplified by accounts of wartime liaisons between black troops and white French women. Such acceptance by French women, it was claimed, would give black veterans the idea that they had sexual access to white Southern women. So as black soldiers returned home to enjoy peace, many Southern whites literally “prepared for war.” [66] Racial violence targeting African American veterans soon followed.

Countless African American veterans were assaulted and beaten in incidents of racial violence after World War I. At least 13 veterans were lynched. Indeed, during the violent racial clashes of Red Summer, it was risky for a black serviceman to wear his uniform, which many whites interpreted as an act of defiance. [67]

On November 2, 1919, Reverend George A. Thomas, a first lieutenant and chaplain, and at least one other black veteran were attacked in Dadeville, Alabama, for wearing “Uncle Sam’s uniform.”

There are many accounts of whites in the South accosting black veterans at railroad stations and stripping them of their uniforms. [68] Three months after returning from the war, black veteran Ely Green was wearing his army uniform while driving in downtown Waxahachie, Texas, when a sheriff’s deputy threatened to “whip [it] off him.” The deputy and three white police officers took Mr. Green out of his car and dragged him for a block, then beat him against a wall with their fists and the barrels of their guns while 50 other men watched. Mr. Green was nearly shot and killed, but a prominent white man who knew him drove by and intervened. After the brutal attack, Mr. Green fled Texas, leaving “the happiest home” and “the only dad” he had known, and did not return to Waxahachie for more than 40 years. [69]

On April 5, 1919, a 24-year-old black veteran named Daniel Mack was walking in Sylvester, Georgia, when he accidentally brushed up against a white man as they passed each other. The white man responded angrily and an altercation ensued, leading to Mr. Mack’s arrest. At his arraignment, Mr. Mack said, “I fought for you in France to make the world safe for democracy. I don’t think you’ve treated me right in putting me in jail and keeping me there, because I’ve got as much right as anyone to walk on the sidewalk.” The judge responded, “This is a white man’s country and you don’t want to forget it.” He sentenced Mr. Mack to 30 days on a chain gang. [70] Mr. Mack was serving his sentence when, on April 14, at least four armed men seized him from his cell and carried him to the edge of town, where they beat him with sticks, clubs, and the butts of guns, stripped him of his clothes, and left him for dead. Despite multiple skull fractures, Mr. Mack made his way to the home of a black family who helped him to escape town. [71]

Ely Green and Daniel Mack survived and managed to flee the South, but many other black veterans did not make it out alive. In Pine Bluff, Arkansas, when a white woman told a black veteran to get off of the sidewalk, he replied that it was a free country and he would not move. For his audacity, a mob took him from town, bound him to a tree with tire chains, and fatally shot him as many as 50 times. [72]

Learn More: Moore's Ford Bridge

On July 25, 1946, two black couples were lynched near Moore’s Ford Bridge in Walton County, Georgia, in what has been called “the last mass lynching in America.” [73] The victims were George W. Dorsey and his wife, Mae Murray, and Roger Malcolm and his wife, Dorothy, who was seven months pregnant. Mr. Dorsey, a World War II veteran who had served in the Pacific for five years, had been home for only nine months.

On July 11, Roger Malcolm was arrested after allegedly stabbing white farmer Barnette Hester during a fight. Two weeks later, J. Loy Harrison, the white landowner for whom the Malcolms and the Dorseys sharecropped, drove Mrs. Malcolm and the Dorseys to the jail to post a $600 bond. On their way back to the farm, the car was stopped by a mob of 30 armed, unmasked white men who seized Mr. Malcolm and Mr. Dorsey and tied them to a large oak tree. Mrs. Malcolm recognized members of the mob, and when she called on them by name to spare her husband, the mob seized her and Mrs. Dorsey. Mr. Harrison watched as the white men shot all four people 60 times at close range. He later claimed he could not identify any members of the mob. [74] The Moore’s Ford Bridge lynchings drew national attention, leading President Harry Truman to order a federal investigation and offer $12,500 for information leading to a conviction. A grand jury returned no indictments and the perpetrators were never brought to justice. The FBI recently reopened its investigation into the lynching, only to encounter continued silence and obstruction at the highest levels. [75] In response to charges that he was withholding information, Walton County Superior Court Judge Marvin Sorrells, whose father worked for Walton County law enforcement in 1946, vowed that “until the last person of my daddy’s generation dies, no one will talk.” [76]

A month after World War I ended, Private Charles Lewis returned home to Tyler Station, Kentucky, where a mob of masked men lynched him on December 16, 1918. [77] Private Lewis was wearing his uniform when he encountered Deputy Sheriff Al Thomas, who attempted to arrest him for robbery. Private Lewis denied guilt and pointed to his uniform, declaring that he had been honorably discharged and had never committed a crime. [78] The two men argued and Private Lewis was charged with assault and resisting arrest. [79] Private Lewis was awaiting transfer to the Fulton County Jail in Hickman, Kentucky, as news of his challenge to white authority spread and a mob of 75 to 100 people formed. At midnight, masked men stormed the jail, smashed the locks with a sledgehammer, pulled Private Lewis out of his cell, tied a rope around his neck, and hanged him from a tree. The next day, hundreds of white spectators viewed Private Lewis’s dead, hanging body, still in uniform. [80] At least 10 more black veterans were lynched in 1919 alone. [81]

Days after Private Lewis’s lynching, Louisiana’s True Democrat newspaper published an editorial entitled “Nip It in the Bud,” summarizing Southern white views of returning black veterans. “The root of the trouble was that the negro thought that being a soldier he was not subject to civil authority,” the paper wrote of Private Lewis. “The incident is a portent of what may be expected in the future as more of the negro soldiery return to civil life.” The editorial board opined that military service had “probably given these men more exalted ideas of their station in life than really exists, and having these ideas they will be guilty of many acts of self-assertion, arrogance, and insolence… there will be much friction before they sink back into their old groove, and accept the fact that social equality will never be accepted in the South.” The editorial board warned that “[t]his is the right time to show them what will and what will not be permitted, and thus save them much trouble in the future.” [82]

Several black World War I veterans were targeted for attack or lynching after the war due to their perceived or actual relationships with white women. An African American veteran and a black woman were lynched near Pickens, Mississippi, on May 5, 1919, because the veteran had allegedly hired the woman to write an “improper note” to a young white woman. [83] In Louise, Mississippi, on July 15, 1919, whites hung Robert Truett, a veteran who was just 18 years old, on allegations that he had made “indecent proposals” to a white woman. [84] On September 10, 1919, a black veteran named L.B. Reed was hung in Clarksdale, Mississippi, after he was suspected of having a relationship with a white woman. [85] A waiter at a café where the woman often ate, Mr. Reed was taken from the Mosby Hotel and hanged from the bridge across the Sunflower River. His body was found on the banks of the river three days later. [86]

On August 3, 1919, a white mob lynched black veteran Clinton Briggs for allegedly “insulting” a white woman in Lincoln, Arkansas, by moving too slowly out of her way as she tried to walk past him. Recently discharged from Camp Pike, Mr. Briggs passed a white couple on the sidewalk and moved only slightly to let the woman pass. She responded angrily and her companion assaulted Mr. Briggs. A mob gathered and threw Mr. Briggs into a vehicle, drove into the wilderness of Lincoln County, chained him to a tree, and riddled his body with bullets. [87]

White mobs lynched black World War I veterans in public spectacles designed to terrorize entire black communities. Veteran Frank Livingston was burned alive in El Dorado, Arkansas, on May 21, 1919, after he was accused of murdering the white couple who employed him. [88] After the couple’s bodies were discovered, a mob seized Mr. Livingston and accused him of murder, then beat and tortured him into allegedly confessing. Black people accused of crimes during the lynching era were often beaten and tortured by lynchers to extort a confession that would “justify” the lynching. Though white newspapers reported such “confessions” as fact, these statements plainly evidenced the accused’s pain and terror, not his guilt.

The next day, with no investigation or trial, more than 100 people gathered to burn Mr. Livingston alive. It was the second lynching of a black person in Arkansas in 30 days. [89] The sheriff arrived after Mr. Livingston was dead and made no arrests, [90] as was common during this era: “The arriving too late of the sheriff, or his inability to check the mob,” a local newspaper noted, “is the rule in some cases.” [91] The NAACP urged the governor to remember his oath to “protect all Arkansas citizens” and launch a formal inquiry into Mr. Livingston’s lynching; he did not respond. [92] None of the lynchers was arrested. [93]

On March 12, 1919, veteran Bud Johnson had traveled to Florida to bury his father and was waiting to board a steamboat home to Alabama when he heard the barking of bloodhounds. The local county sheriff arrested Mr. Johnson because he allegedly matched the description of a man accused of assaulting a white woman in Pace, Florida. On the way to Jacksonville, a mob overtook the police car, seized Mr. Johnson, and took him to Pace. The mob tortured Mr. Johnson, distributed $66 they found in his pockets, chained him to a stake, burned him alive, crushed his skull with a hatchet and gave the pieces to onlookers as souvenirs, and discarded his corpse in a nearby swamp. After the mob dispersed, Mr. Johnson’s loved ones had to battle alligators to recover his remains for burial. [94]

NAACP Secretary John Shillady wrote to Florida Governor Sidney Catts to protest Bud Johnson’s brutal lynching. Governor Catts replied that nothing could have protected Mr. Johnson from the mob. “You ask me to see that these lynchers are brought to trial,” he wrote. “This would be impossible to do as conditions are now in Florida, for when a Negro brute, or a white man, ravishes a white woman in the State of Florida, there is no use having the people who see that this man meets death brought to trial, even if you could find who they are: the citizenship will not stand for it.” [95] In Florida and throughout the country, government officials were not inclined to protect the rights or the lives of black Americans, not even those who had risked their lives to protect and defend their country.

On August 31, 1919, in Bogalusa, Louisiana, when a black veteran named Lucius McCarty was accused of attempted assault on a white woman, a mob of 1500 people gathered and shot him more than 1000 times. The mob dragged his body behind a car through the town’s African American neighborhoods and then burned his corpse in a bonfire. [96] On December 27, 1919, officers transporting veteran Powell Green to jail in Raleigh County, North Carolina, were overpowered by a mob. Mr. Green had been accused of shooting R.M. Brown, the white owner of a movie theater in Franklinton. The mob tied a rope around Mr. Green’s neck, dragged him for two miles behind an automobile, and then hung him from a pine sapling. “[N]early the entire town” fought over scraps of his clothing, his watch and chain, and chips from the pine tree. [97] These public spectacle lynchings were designed to terrorize and intimidate the entire African American community by torturing and mutilating victims in front of massive crowds, and they succeeded in horrifying and traumatizing generations of African Americans.

Learn More: Hosea Williams

Celebrated civil rights leader Hosea Williams was threatened by a lynch mob at the age of 14 in Attapulgus, Georgia, for befriending a white girl. Even after this terrifying experience of racial violence, Mr. Williams enlisted to serve in World War II as part of the all-black unit of General George Patton’s Third Army. During a battle in France, an artillery shell hit Mr. Williams’s platoon, killing the other 12 soldiers and wounding Mr. Williams; when the ambulance transporting him to the hospital was hit by another artillery shell, Mr. Williams was again the lone survivor and spent 13 months at a British hospital recovering from his injuries.

After the war, Mr. Williams headed home to Attapulgus with a Purple Heart and the assistance of a cane. While he was wearing his uniform, Mr. Williams was brutally assaulted by a mob of white men at the bus station in Americus, Georgia, after he attempted to drink out of the white-only drinking fountain. The mob left him for dead. People at the bus station called the town’s black undertaker, who found a pulse and brought Mr. Williams to the Veterans Administration hospital. Lying in the hospital for eight weeks due to his new, “peacetime” injuries, Mr. Williams found himself lamenting that he “had fought for the wrong side.”

Nearly lynched, nearly killed abroad, and nearly lynched again upon returning home, Hosea Williams survived and continued to fight for human rights. He went on to help organize the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, served as Executive Director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and was jailed more than 125 times for participating in civil rights demonstrations. Mr. Williams relentlessly challenged his country to honor at home the ideals of freedom and equality it fought for abroad. [98]

Lynching escalated in the post-war years, terrorizing black Americans with threats of violence and death and fueling a massive exodus of black refugees out of the South to cities in the North and West. A tool of racial control used to enforce white dominance, lynching surged while black veterans returned to their communities as potential leaders and defenders. Many of these veterans were targeted precisely because their status threatened to upend the myth of racial inferiority on which the ideology of white supremacy relied.

During this period, black veterans became widely associated in the minds of many white people with an attitude of defiant resistance that could prove deadly in a society where racial subordination was violently enforced. This perception put black veterans in jeopardy even years after the war, and many black veterans were killed as a result of being continuously targeted for racial violence. On January 10, 1922, a white mob chased down and shot to death William “Willie” Jenkins, a young black World War I veteran who was accused of insulting a white woman near Eufala, Alabama. The mob reportedly captured Mr. Jenkins just across the Georgia state line and brought him back to Eufala, where he escaped only to be recaptured. His body was later found on the side of the road, about four miles from town, riddled with bullets. [99]

In 1937, a veteran named Earnest McGowan refused to accept his victimization at the hands of a white mob and reported to the authorities in Waller County, Texas, that he had been attacked and wrongly accused of stealing cattle. In response, the mob found Mr. McGowan and killed him. [100] On April 29, 1939, World War I veteran Lee Snell was driving a taxi in Daytona Beach, Florida, when he accidentally struck and killed a white 12-year-old who was riding a bicycle. Mr. Snell was arrested and charged with manslaughter. During a transfer between jails, two brothers of the deceased child stopped the police car and fatally shot Mr. Snell. Officers did not use force to apprehend the men, and as the brothers drove away, they called out to the constable, “I’ll see you after the funeral.” The brothers were charged with murder, but the constable declined to identify them at trial and a jury acquitted them of all wrongdoing. [101]

Precious E. Grant, a black World War I veteran, was arrested in March 1943 based on the statement of a white woman who said he had attempted to rape her. The woman admitted she had never seen her assailant; she claimed he had grabbed her from behind and fled when she screamed. Mr. Grant was arrested and jailed on March 21 and held for several months awaiting a trial that would never come. On November 28, two white men seized Mr. Grant from his cell, killed him, and left his corpse in the woods for the birds. [102]

Marching Toward a Movement: Black Service in World War II

Lynching and racial violence surged after World War I, impeding widespread social activism and progress. The immediate post-war decades saw few changes in the overall social, political, and economic status of black Americans. Despite their hopes, the service, sacrifice, and heroism of black veterans failed to secure their full citizenship. As the United States prepared to enter World War II, its treatment of African Americans increasingly came under scrutiny — especially “in light of World War II sloganeering” [103] about democracy and human rights — and a new generation considered whether, this time, military service might force progress.

Despite the disappointment African Americans experienced after World War I, black leaders nonetheless sought to leverage the United States’s war rhetoric to ensure equal treatment for African American servicemen during World War II, including the chance to fight in combat and earn the respect afforded to combat troops. Leaders like Dr. Du Bois had urged black Americans to put their grievances aside during the First World War, but this time, black recruits refused to enlist without assurances that they would have full access to the military’s varied roles and rewards. [104]

As the United States entered the Second World War, African Americans created the “Double V” Campaign, which called for victory over fascism abroad and victory over racism at home. The Pittsburgh Courier, a black newspaper, coined the slogan and was influential in launching the campaign. “In our fight for freedom,” the editorial board wrote, “we wage a two-pronged attack against our enslavers at home and those abroad who would enslave us.” [105]

African Americans continued to reckon with a country that claimed to be fighting for freedom and democracy abroad while denying freedom and justice to its own citizens. As Roy Wilkins, editor of NAACP magazine The Crisis, wrote, “Who wants to fight for the kind of ‘democracy’ embodied in the curses, the hair-trigger pistols, and the clubs of the Negro-hating hoodlums in the uniforms of military police?” [106]

The Double V Campaign created some legal and policy changes but failed to achieve equality. The Selective Service of Act of 1940 allowed African Americans to join the military in numbers proportional to their representation in the country, provided for white and black officers to train together, and established aviation training for black officers, but also maintained segregation.

In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 8802 outlawed racial discrimination in the war industry. But the enforcement body he established — the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) [107] — had no authority to regulate employment practices and faced increased resistance from Southern states. Rather than agree to the FEPC’s nondiscrimination requirements, Alabama Governor Frank Dixon refused a government contract to operate cotton mills in state prisons for war production. [108] Without Southern participation, the FEPC was doomed to failure.

By 1942, nearly one year after President Roosevelt created the FEPC, African Americans comprised less than 3 percent of all war workers. In 1946, Southern Democrats in the Senate gutted the FEPC by eliminating its funding, and by June 1946, the committee had ceased to function. [109]

African Americans nonetheless joined up in increasing numbers. In 1941, fewer than 4000 African Americans were serving in the armed forces, and only 12 were officers. By 1945, more than 1.2 million black men were in uniform. Even as the United States proclaimed itself the world’s greatest democracy, it was fighting the racism of Hitler’s Germany with an army that remained racially segregated through the end of the war. Black troops initially were barred from frontline combat and assigned to service duties, cleaning white officers’ rooms and latrines as orderlies and janitors. [110] But as casualties mounted, the army sent African American troops into combat out of necessity.

No matter the sacrifices of black servicemen, Jim Crow remained the law of the land at home and in the service. Black military policemen stationed in the South could not enter restaurants where their German prisoners of war were allowed to eat. Private Bert Babero wrote that he was required “to observe a sign in the latrine, actually segregating a section of the latrine for Negro soldiers, the other being used by the German prisoners and the white soldiers.” He recalled, “[I]t made me feel here, the tyrant, is actually placed over the liberator.” [111]

Racial discrimination extended to veterans’ benefits as well. Black soldiers were denied access to programs like the G.I. Bill of Rights, which was designed to reward military service and assist veterans with housing, education, and employment. The G.I. Bill was “the most wide-ranging set of social benefits ever offered by the federal government in a single, comprehensive initiative,” [112] and is often credited with creating the American middle class. Between 1944 and 1971, the federal government spent more than $95 billion to provide benefits to veterans; in 1948, the G.I. Bill made up 15 percent of the federal budget. It created opportunities for home ownership, higher education and vocational training, and provided capital for veterans to start their own businesses. Before the war ended, black publications printed digests of the legislation and outlined the eligibility requirements. The G.I. Bill gave black soldiers and their communities a sense of hope that their service would entitle them to unprecedented opportunities for economic advancement. [113] Unfortunately, those hopes went largely unrealized.

Foreseeable flaws in the administration of the G.I. Bill led to a middle class that was overwhelmingly white. Like other New Deal legislation, the G.I. Bill “was deliberately designed to accommodate Jim Crow;” [114] indeed, racist administration of veterans’ programs was presumed. Senator John Ranklin of Mississippi chaired the Committee on World War Legislation, and supporters of the bill, including the Veterans Administration, knew it would not pass without Southern support. Though the bill contains no language mandating racial segregation or excluding African Americans, it was crafted to strictly limit federal oversight. Because the bill gave all administrative responsibility to the states, with little congressional supervision, state authorities had virtually unchecked power to discriminate against black veterans. [115]

Racial discrimination pervaded veterans’ programs, but the effects were particularly acute in the provision of home loans. Title III of the G.I. Bill made veterans eligible for low-interest home loans with no down payment. Very few black veterans benefitted from Title III because, while the loans were guaranteed by the VA, they required cooperation from local banks. This meant that veterans first had to convince local banks to lend to them — which proved a daunting task for black veterans because the overwhelming majority of banks routinely denied loans to black applicants. [116]

Home ownership was the primary driver for post-war economic security and wealth accumulation, and it spurred the creation and growth of suburban white America. The G.I. Bill’s failure to provide similar uplift for black veterans and their families was evident from the start. A survey of 13 Mississippi cities found that African Americans received only 2 of the 3229 home, business, and farm loans administered by the VA in 1947. The Pittsburgh Courier charged that “the veterans’ program had completely failed veterans of minority races.” [117] Once again, black people were excluded from the benefits of military service, and the hopes of black veterans and their communities were crushed by an unyielding racism that barred their entry into the middle class.

Learn More: Veterans and Capital Punishment

The legacy of violence against African American veterans is reflected in the disproportionate number of veterans sentenced to death in the United States. Nationwide, 300 veterans are on death row today. About 7 percent of Americans have served in the military, but about 10 percent of people sentenced to death in the United States are veterans. [118] Just as serving in the military failed to protect black veterans who fought in the Civil War, World War I, and World War II, military service in Vietnam and recent conflicts fails to prevent their executions.

Robert Fisher earned a Purple Heart in Vietnam, which was awarded by President Lyndon Johnson himself. Mr. Fisher is now in his late 60s and is condemned to die by execution in Pennsylvania. Though there was evidence that at the time of the crime he was suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as a result of his military service, no mental health expert testified at his sentencing. [119]Many of the veterans sentenced to death suffer from PTSD and other mental illnesses directly related to their combat service. Manny Babbit, a Marine who did two tours in Vietnam, came home with shrapnel in his skull from injuries sustained in battle. He was sentenced to death by an all-white jury in California. He was awarded a Purple Heart in a prison ceremony in 1998; soldiers presented the medal and saluted Corporal Babbitt; he was shackled and could not return the salute. California Senator Dianne Feinstein later introduced legislation to ban the presentation of medals to incarcerated veterans. On May 4, 1999, Corporal Babbitt was executed after he declined his last meal and requested that the $50 allotted be given to homeless veterans. [120]

On February 13, 1946, armed members of the Ku Klux Klan abducted Hugh Johnson, a 21-year-old black navy veteran working as a bellboy at an Atlanta hotel, took him to a desolate area outside of Atlanta, and whipped him 50 times. [130]

On August 8, 1946, black World War II veteran John C. Jones was lynched in Minden, Louisiana, for allegedly entering a white family’s back yard and looking through the window at a young white woman. [131] Mr. Jones’s 17-year-old cousin, Albert Harris, was also accused, beaten, and left for dead, but he survived the attack and fled to Michigan in fear for his life. [132] The Pittsburgh Courier observed that Mr. Jones “had answered Uncle Sam’s call for red-blooded men to fight for democracy abroad, even though he had never experienced democracy at home.” [133]

Pressure from the NAACP led to federal charges against several law enforcement officials and residents involved in Mr. Jones’s lynching. Albert Harris testified at trial, “still covered with scars left by the lynchers’ ropes and bludgeons.” The all-white jury nonetheless acquitted the defendants after deliberating for less than two hours. “Another veteran of World War II who emerged unscathed from the holocaust has been done to death on his native soil and has gone unavenged,” the Pittsburgh Courier concluded. [134

]On August 17, 1946, less than two weeks after Mr. Jones was killed, a black veteran named J.C. Farmer was “merrily laughing” while waiting for a bus with two friends in Wilson, North Carolina. When a police officer ordered Mr. Farmer into his patrol car, Mr. Farmer replied that he had done nothing wrong. The policeman struck him on the head, and in the ensuing struggle, the officer’s gun went off, shooting the white officer through the hand. Within an hour, a lynch mob had formed and Mr. Farmer was dead. [135]

African American veterans who asserted their economic and political rights upon returning from service were met with especially violent resistance. Veteran Eugene Bells angered local whites when he refused to work for the white farmers in Mississippi after returning from World War II, and instead chose to work on his father-in-law’s farm. On August 25, 1945, Mr. Bells was driving his car in Amite County with Hilton Lea and several other passengers when a car carrying three white men began to follow them. When the white men opened fire, Mr. Bells pulled over in fear. The men beat Mr. Lea unconscious and then took Mr. Bells to a swamp, where they beat him severely enough to crush his skull and then shot him in the head. [136]

During World War II, black communities in the United States faced an unrelenting onslaught of racial attacks. The resulting unrest sparked clashes between black and white people, which in turn provoked violent reprisals against black communities. In June 1943, so-called riots in Beaumont, Texas, and Detroit, Michigan, led to deaths, injuries, economic loss, and deepened racial hostility. [121] In this environment, returning black veterans were not only denied benefits and the opportunities for economic advancement they had been promised, but they were also burdened by their veteran status and military service, which made them prime targets for racial violence — especially if they publicly challenged Jim Crow segregation.

For many veterans, their first confrontation with the post-war racial caste system occurred on the bus or train that carried them home. On February 8, 1946, honorably discharged Marine Timothy Hood removed the Jim Crow sign from a trolley in Bessemer, Alabama. In response, the white street car conductor, William R. Weeks, unloaded his pistol into Mr. Hood, firing five shots. [122] Mr. Hood staggered off the tram and crawled away, only to be arrested by the chief of police, G.B. Fant of Brighton. Fant put Mr. Hood in the back of a police car and murdered him with a single bullet to the head. [123] Fant later alleged that Mr. Hood had “reached toward his hip pocket as if to draw a gun.” Although there was no evidence that Mr. Hood was armed, the coroner returned a finding of “justifiable homicide,” and Fant was cleared. [124]

On February 24, 1946, in Columbia, Tennessee, James Stephenson, a 19-year-old navy veteran, wore his uniform to accompany his mother to the store. When his mother told the clerk she was not satisfied with the store’s service, the clerk slapped her, and Mr. Stephenson punched the clerk. Remembering two lynchings in the community 13 years earlier, local black business owners quickly arranged to transport Mr. Stephenson and his mother out of town to avoid a growing white mob. [125] Mr. Stephenson’s lynching was avoided, but the mob waged a two-day attack on Columbia’s black community, vandalizing the black business district and arresting more than 100 black people, including two who died in police custody. [126]

On February 12, 1946, Isaac Woodard, a black veteran who had served in the Philippines, boarded a Greyhound bus in Georgia, headed home to his wife in North Carolina. When the bus stopped just outside of Augusta, South Carolina, Mr. Woodard asked the driver if there was time to use the restroom, and the driver cursed at him. After a brief argument, Mr. Woodard returned to his seat. At the next stop in Batesburg, the angry driver told Mr. Woodward to exit the bus, where the local chief of police, Linwood Shull, and several other police officers were waiting.

The police beat Mr. Woodard with billy clubs and arrested him for disorderly conduct, accusing him of drinking beer in the back of the bus with other soldiers. Upon arrival at the police station, Shull continued to strike Mr. Woodard with a billy club, hitting him in the head so forcefully that he was permanently blinded. [127] The next morning, a local judge fined Mr. Woodard $50 and denied his request for medical attention. By the time of his release days later, Mr. Woodard did not know who or where he was. His family found him in a hospital in Aiken, South Carolina, three weeks later, after reporting him missing. “Negro veterans that fought in this war… don’t realize that the real battle has just begun in America,” Mr. Woodard later said. “They went overseas and did their duty and now they’re home and have to fight another struggle, that I think outweighs the war.” [128]

By the mid-20th century, violent racialized attacks on black veterans were slightly more likely to result in investigations and charges against the white perpetrators, but they rarely led to convictions or punishment, even when guilt was undisputed. Under pressure from the NAACP, the federal government eventually charged Chief Shull for the attack on Mr. Woodard, but the prosecution was half-hearted at best. The United States Attorney did not interview any witnesses except the bus driver.

At trial, Shull admitted that he had blinded Mr. Woodard, but Shull’s lawyer shouted racial slurs at Mr. Woodard and told the all-white jury, “[I]f you rule against Shull, then let this South Carolina secede again.” After deliberating for 30 minutes, the jury acquitted Shull of any wrongdoing, and the courtroom broke into applause. Remarking on the outcome, Mr. Woodard said, “The Right One hasn’t tried him yet… I’m not mad at anybody… I just feel bad. That’s all. I just feel bad.” [129]

In August 1946, veterans Alonza Brooks and Richard Gordon were murdered in Marshall, Texas, after becoming involved in labor disputes with their employers. When found, Mr. Brooks’s body bore signs of strangulation, while Mr. Gordon’s throat was slashed and his body appeared to have been tied to the rear of an automobile and dragged. [137]

Maceo Snipes had served in the army for two and a half years and received an honorable discharge when he returned home to Taylor County, Georgia, to farm his father’s land. On July 17, 1946, Mr. Snipes voted in the Democratic primary for governor. The next day, several white men in a pick-up truck went to Mr. Snipes’s house and a white veteran named Edward Williamson shot him. Mr. Snipes walked for several miles seeking help, but died before he could find any. Williamson, who belonged to a politically powerful family, told a coroner’s inquest that he had gone to collect a debt from Mr. Snipes and Mr. Snipes pulled a knife on him. The inquest ruled the killing was an act of self-defense. Taylor County, Georgia, later honored its World War II veterans with two engraved, segregated plaques listing white and black veterans separately. Though an integrated plaque was added in 2007, the segregated originals remained. [138]

The discrimination, violence, and inhumanity black veterans faced when they returned home from World War II illustrated the continuing chasm between the ideals that the United States claimed to fight for abroad and the treatment of its citizens at home — two separate realities of the veteran experience, distinguished by skin color.

Conclusion

African Americans served in the Civil War, World War I, and World War II for the ideals of freedom, justice, and democracy, only to return to racial terror and violence. American individuals and institutions intent on maintaining white supremacy and racial hierarchy targeted black veterans for discrimination, subordination, violence, and lynching because they represented the hope and possibility of black empowerment and social equality. That hope threatened to disrupt entrenched social, economic, and political forces, and to inspire larger segments of the black community to participate in activism that could deal a serious blow to the system of segregation and oppression that had reigned for nearly a century and was rooted in a myth of racial difference older than the nation itself.

Despite the overwhelming injustice and horrific attacks black veterans suffered during the era of racial terror, they remained determined to fight at home for what they had helped to achieve abroad. This commitment directly contributed to the spirit that would launch the American Civil Rights Movement, and the courage that would sustain that movement through years of violent and entrenched opposition. Hosea Williams of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Medgar Evers of the Mississippi NAACP, and Charles Sims and Ernest Thomas of the Deacons for Defense, are just a few leaders of the civil rights era who returned to the United States as World War II veterans who were targeted for violence but determined to make change. [139]

Highlighting and honoring the particular burden borne by black veterans during the lynching era is critical to recovering from the terror of the past as we face the challenges of the present.

Notes

- 1. Philip Klinkner and Rogers Smith, The Unsteady March: The Rise and Decline of Racial Equality in America 167 (2002).

- 2. Langston Hughes, The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes 281 (1994).

- 3. Chad Williams, Torchbearers of Democracy 238 (2010).

- 4. Roy Reed, Alabama Police Use Gas and Clubs to Rout Negroes, N.Y. Times (Mar. 8, 1965).

- 5. Christopher S. Parker, Fighting for Democracy: Black Veterans and the Struggle Against White Supremacy in the Postwar South 41 (2009).

- 6. Adriane Lentz-Smith, Freedom Struggles: African Americans and World War I 17 (2009).