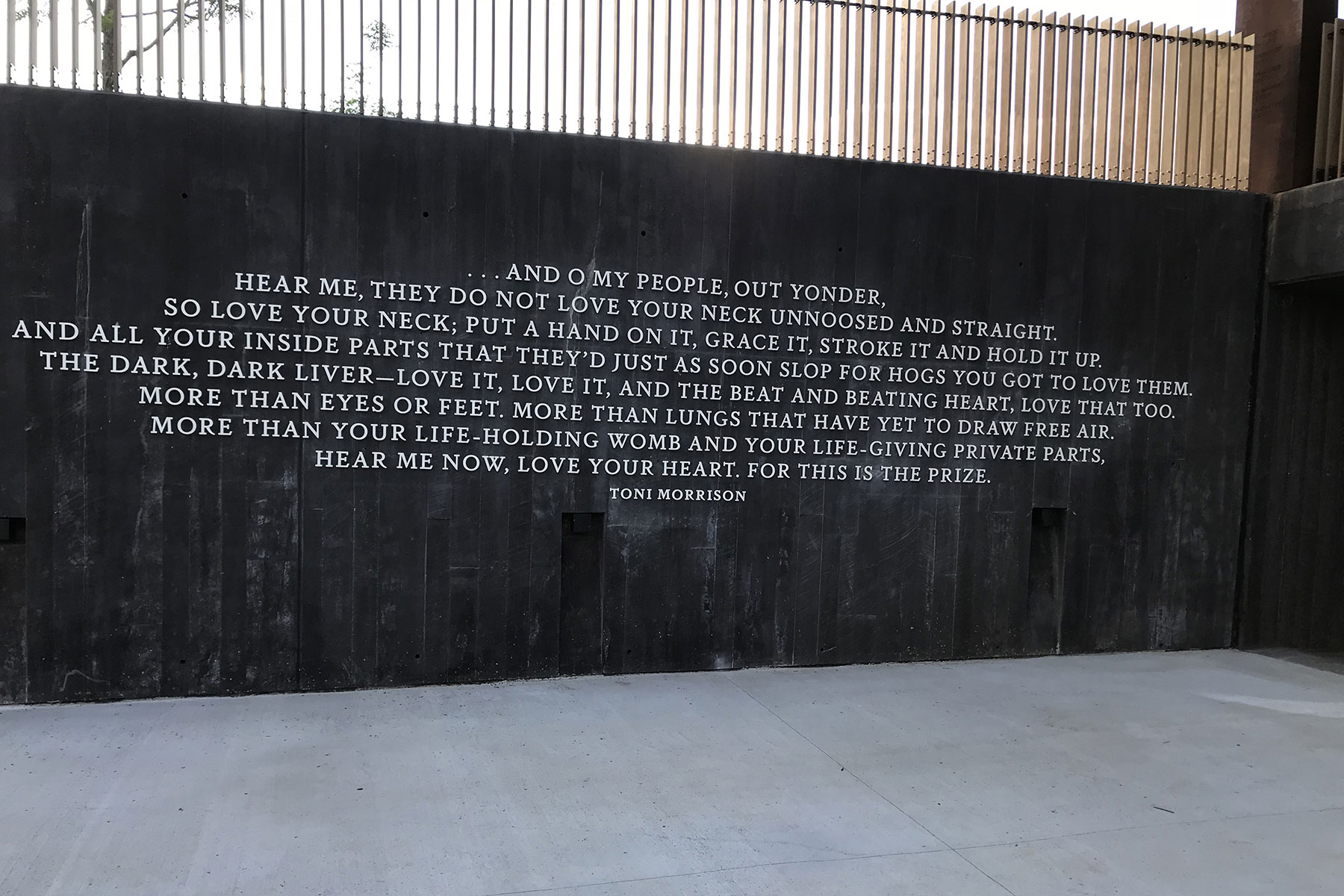

It was a glimpse of the Beloved Community: the American Dream Dr. King envisioned for the United States over fifty years ago. Black and white together, overcoming. And overcome by emotion at the profound rightness of the moment. Strangers turning to each other for connection and deep dialogue in the Museum. Americans of all ages and backgrounds gazing in somber communal reflection at the columns, heavy with names, hanging over their heads in the Memorial.

Over the week of April 26, I joined friends, colleagues, and 7,000 other Americans in Montgomery, Alabama. We came from all around the country to attend the opening of the Equal Justice Initiative’s (EJI) Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and its 2-day Summit Conference.

I have visited memorials and museums on four continents and have never seen spaces more beautifully designed to help the public come to terms, both intellectually and psychologically, with some terrible truths.

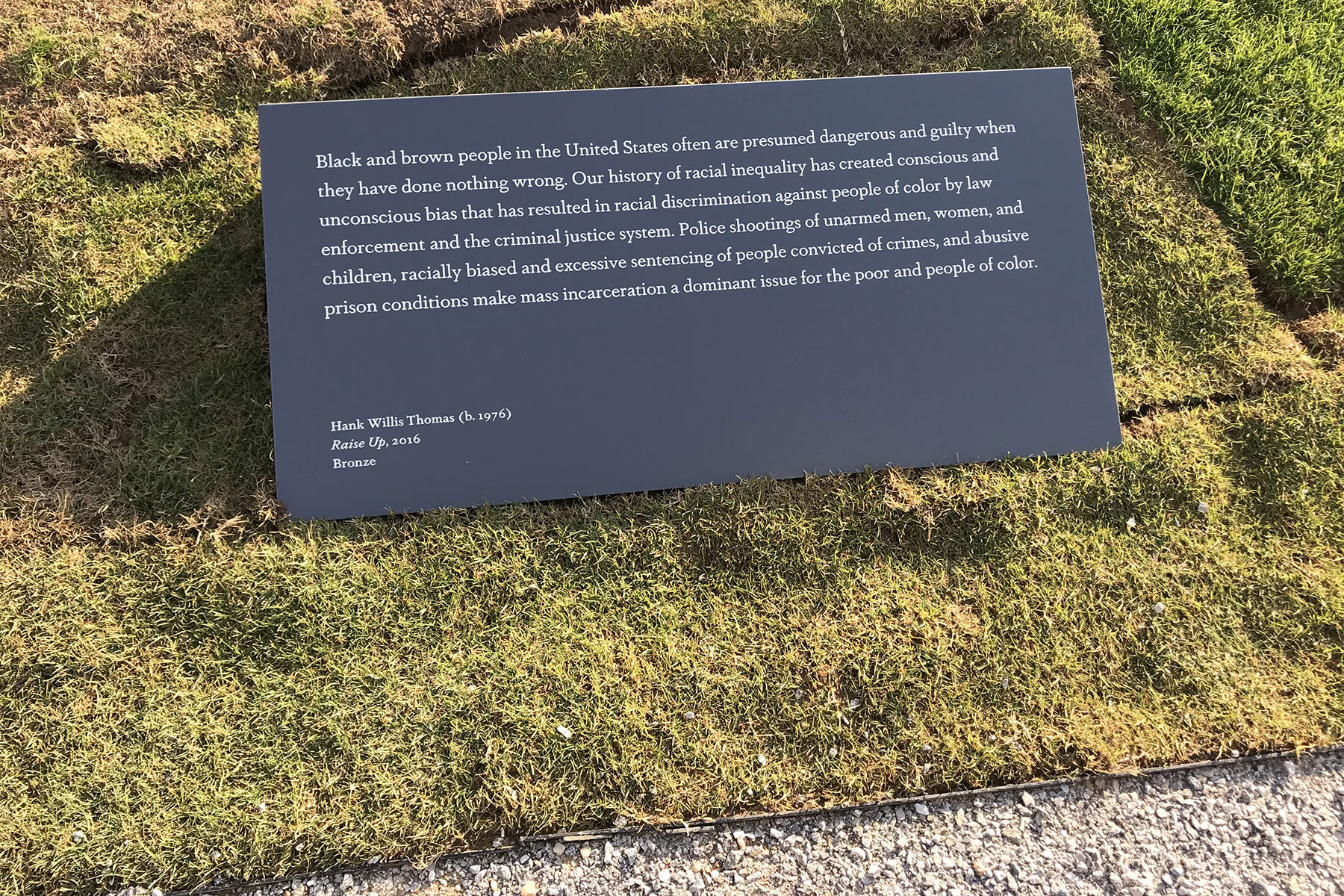

EJI’s compact Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration tells its powerful stories through works of art, photography, film, and technology, along with very well-written museum texts. They reveal how we got from there to here, how the legacy of our nation’s first 256 years – during which we held millions of humans in bondage – has led to our country’s current status as the world’s biggest jailer of its citizens and, disproportionately, of people of color.

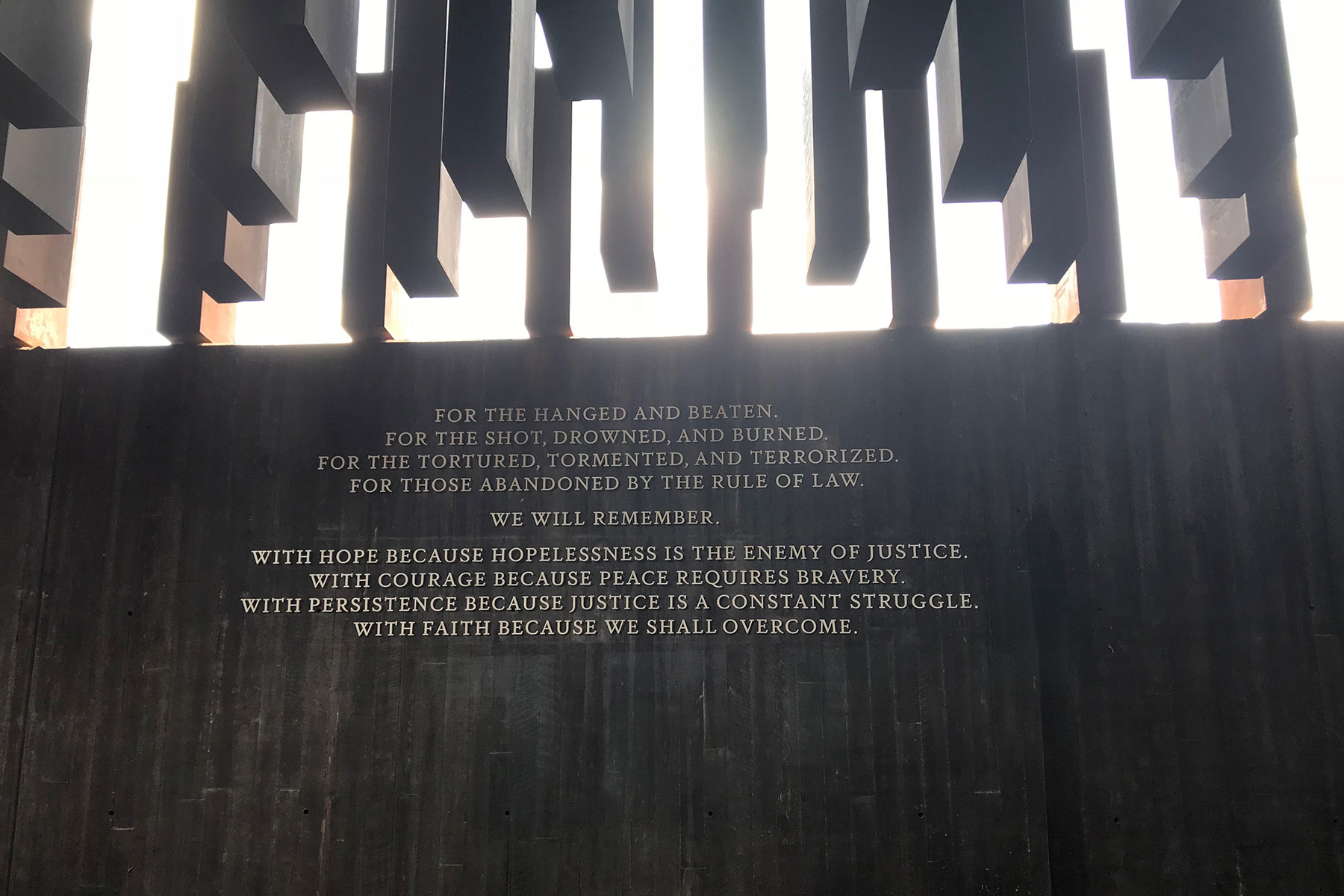

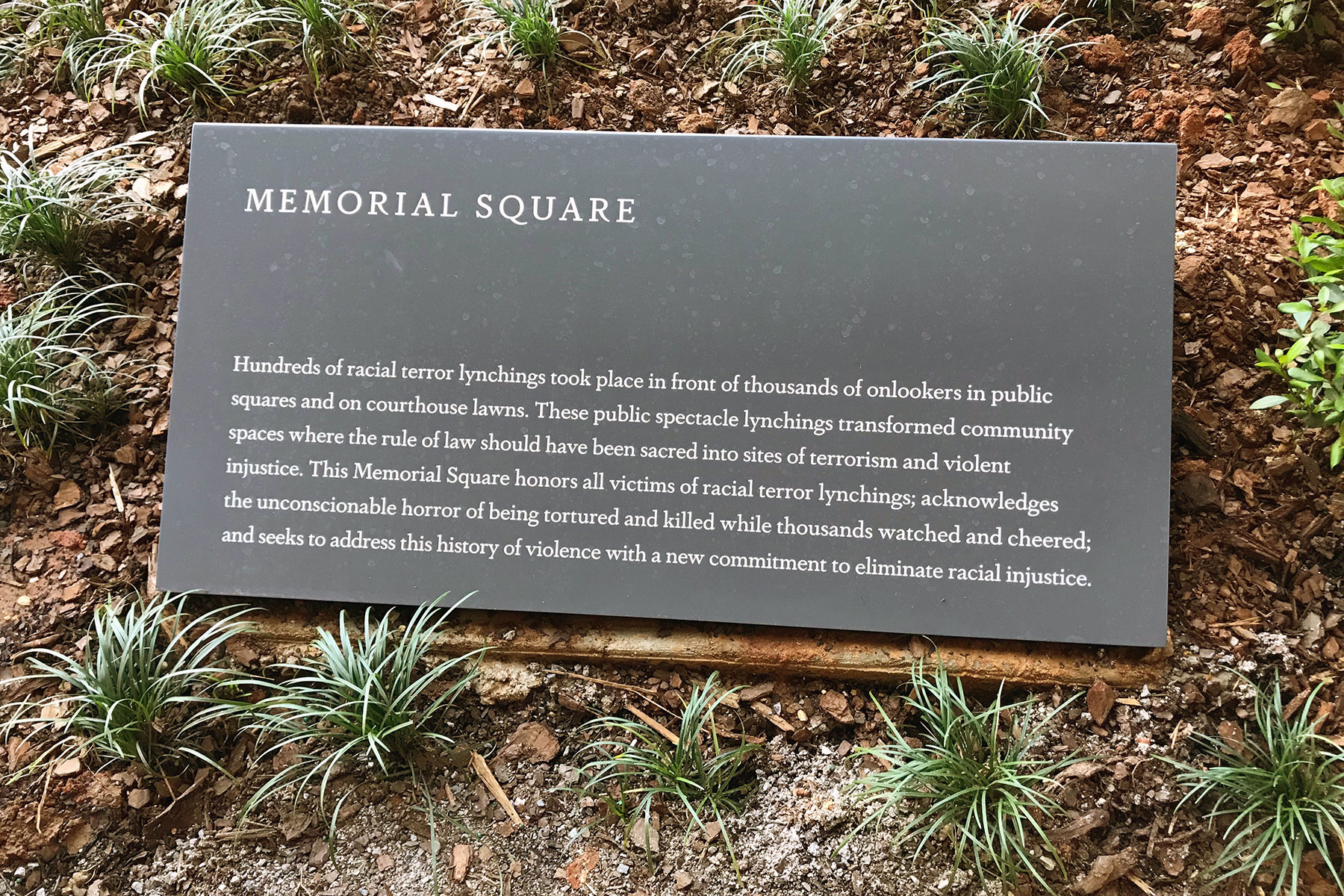

EJI’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice illuminates what occurred during the hundred years that followed the end of slavery and preceded the Civil Rights Movement, a period few Americans learn about in history class. This was a era of racial terrorism: night raiding, cross-burning, and the slavery-by-another-name called “convict leasing.” But nothing sustained inequality more than racial terror lynchings.

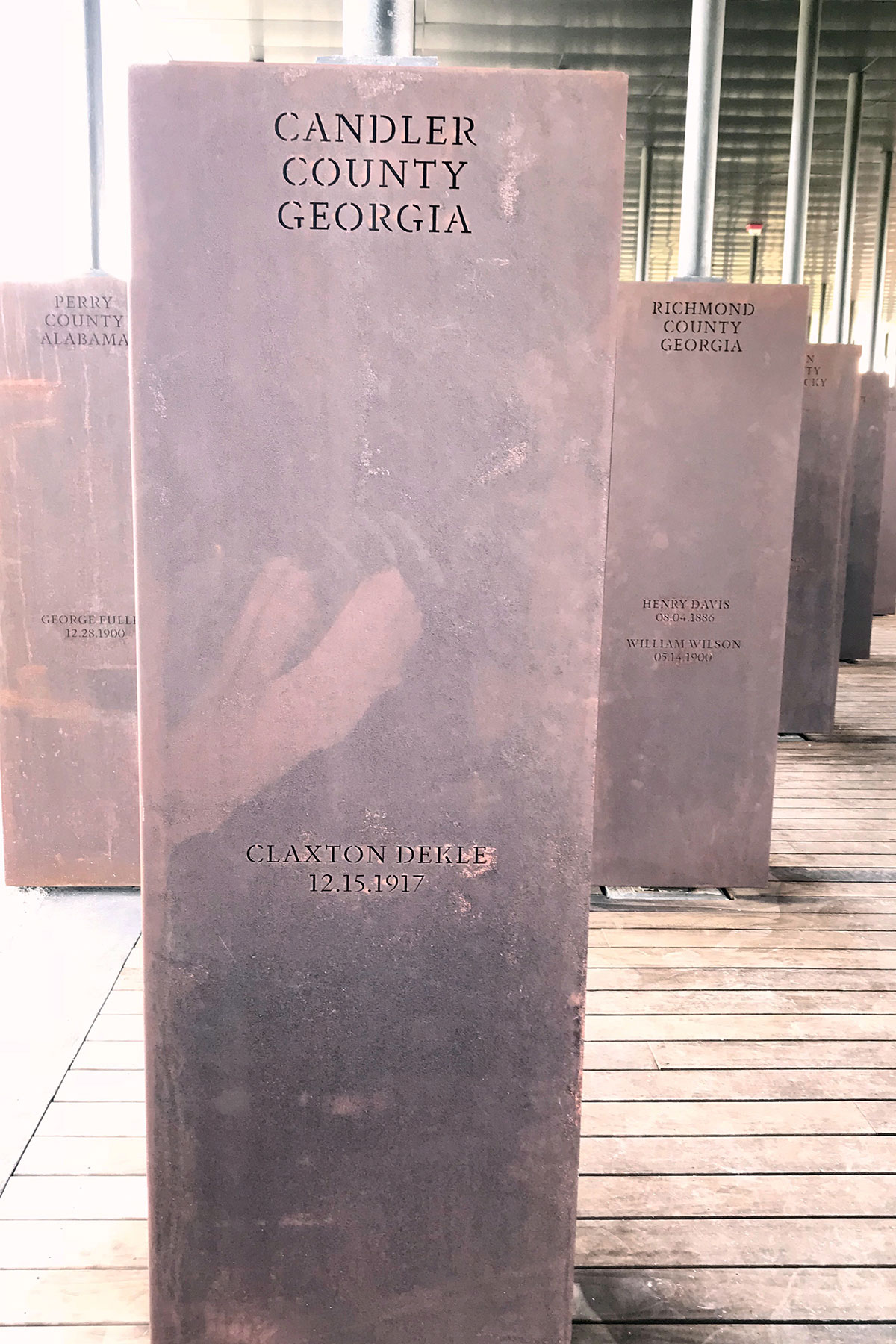

In the Memorial, which has effectively broken the silence about our country’s form of domestic terrorism, people walked in hushed reverence among hundreds of rectangular coffin-sized bronzed columns. Each is etched with the name of a state and its county, and the names and death dates of the men, women, and children who were lynched there. The first columns stand eye level on the floor, but as visitors move further into the Memorial, they begin to rise little by little towards the ceiling, until they hang heavily over your head.

Walking among them, I looked for the victims whose names and stories, and sometimes faces, I know. Right away near the entrance, I found Claxton Dekle of Georgia, a hardworking 24-year old farmer. He was the father of a toddler with another baby on the way, who had tried to return a blind mule to the seller that cheated him. His great-great-nephew sent me his Uncle Clax’s life story to be posted in an online Memorial to the Victims of Lynching. This memorial was among the earliest galleries of what has become the 3,000+ page America’s Black Holocaust Virtual Museum (ABHM). In 2011, volunteers and I transcribed and posted nearly 2,000 names of documented lynching victims.

The purpose of ABHM’s online Memorial is to commemorate not only their deaths, but also their lives. The home page of ABHM’s Virtual Memorial reminds visitors that

each of these victims was once a living human being with feelings, hopes and dreams. But the drama of their deaths has overshadowed their lives. We must remember that each individual had talents and pleasures like singing, dancing, telling stories, playing cards or sports, and creating beautiful and useful things. Each worked for a living or struggled with unemployment. Each was part of a family and community: a father or mother, husband or wife, son or daughter, friend or neighbor, each had loved ones who retrieved the mutilated body and grieved over it.

We encourage family members to send us whatever they know about the life of their loved ones. The first person to do so was Doria D. Johnson, a public historian and PhD candidate at UW-Madison. Doria was an early and persistent advocate for seeing lynching recognized as racial terrorism and naming its victims. She sent me her great-great-grandfather Anthony Crawford’s story and portrait. Despite being run out of town and losing their land following his murder, Doria’s family was never silenced by the shame and trauma many families experienced at being violated in such an inhuman way. They passed this history down through the generations. We published Crawford’s life story and portrait in ABHM’s Virtual Memorial in 2012.

In 2016, Doria and her family participated in a public ceremony that erected a plaque about his life and lynching in Abbeville, South Carolina, where this prosperous black farmer was murdered for daring to haggle over the price of cottonseed with a white merchant. This was part of EJI’s Community Remembrance Project, a campaign that recognizes victims by helping their families and communities collect soil from the sites of lynchings. These jars of soil, marked with the names of each victim, the dates and places of their deaths, are now part of EJI’s new Legacy Museum.

Doria was instrumental in getting the U.S. Senate to publicly apologize in 2005 for never passing any of the anti-lynching legislation brought before it over the hundred bloody years of the practice. She passed away this year at the age of 56, brought down by breast cancer, a disease that affects a disproportionately high percentage of African American woman. It is now believed to be a marker of the unconscionable amount of stress in the lives of black women. I was sad to be unable to find her great-great-grandfather’s name among the thousands in the EJI Memorial, and sadder still that Doria did not live to see it open.

A young EJI staffer helped me find the hanging column with the names of the two victims whose stories I know best: Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith. These teenagers were killed in 1930 in Marion, Indiana, not far from the town where I was later born and raised. I did not learn of this lynching, attended by an estimated ten to fifteen thousand spectators, until I met Dr. James Cameron, founder of America’s Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee.

I first visited ABHM in 1998. My visit began with a film about that lynching and a personal recounting of the experience by Dr. Cameron. With the noose already tightening around his neck, he was miraculously saved. The horror of this 16-year-old kid being beaten nearly to death by people he knew and worked for, of witnessing the torturous deaths of his friends, of the celebratory faces of the spectators professionally photographed beneath those lifeless bodies, left me shaken and speechless.

Little did I imagine that a few years later I would be privileged to work closely with Dr. Cameron and his family on a film about his life, to help publish an expanded edition of his memoir, A Time of Terror: A Survivor’s Story, and to take part in a community effort to reestablish his museum. The more I learned about the life of this amazing scholar-activist, the more deeply I came to appreciate his visionary contributions to our community and country. The legacy he left us profoundly transformed my life, and that of countless others.

In his speech at the opening ceremony for the Memorial and Museum, civil rights pioneer and Congressman John Lewis recognized Dr. Cameron as the only known survivor of a lynching. But he was much more than a survivor. Dr. Cameron worked tirelessly for the remainder of his ninety-two years to help our country realize its founding ideals of liberty and justice for all. He wrote, taught, organized NAACP chapters, spoke out, and mortgaged his home to build, with his own hands, the first memorial museum to the black holocaust in America. He did so that the light of history’s truth might set us free. He fervently believed in our country’s potential for racial repair and reconciliation.

While in the Memorial, I felt the need to do something special to recognize Dr. Cameron’s unseen presence there and honor his life’s work. I knew that each of the 800+ counties where a lynching had taken place would be represented by two identical monuments: one hanging inside, the other lying on the ground outside, waiting to be claimed and taken back to counties wishing to acknowledge that part of their histories. I hoped to be permitted to place small stones for Tommy and Abe on their coffin-like monument, the way we Jews leave such stones as remembrances when we visit the tombs of our loved ones. I carried an additional stone for each of them on Dr. Cameron’s behalf. He surely would have wanted to honor his friends here. Sadly, I was unable to locate their monument among the hundreds lying atop the grassy hill. There is as yet no map, such as cemeteries have to help mourners.

But while I mourn, I also rejoice. In my fifty-some years of doing racial justice work and education, I have never seen so many white people so concerned as in this past year. At his lectures on racial issues like Milwaukee’s hyper-segregation, my consulting partner, Reggie Jackson, regularly draws large crowds in small, virtually all-white Wisconsin towns and suburbs. Maybe we are finally ready to talk honestly and openly about this “family secret,” to attend to a festering wound so that our collective healing can begin.

In Montgomery, where Dr. King’s ministry and the Civil Rights Movement began, I felt the stirrings of a new movement. I felt embraced and rocked in the bosom of a Beloved Community – of a people finally becoming whole.

“Lynching in America was not isolated hate crimes committed by rogue vigilantes. Lynchings were targeted racial violence perpetrated to uphold an unjust social order. Lynchings were terrorism.

This era left thousands dead; significantly marginalized black people politically, financially, and socially’ and inflicted deep trauma on the entire African American community. White people who witnessed, participated in, and socialized their children in a culture that tolerated gruesome lynchings also were psychologically damaged. State officials’ tolerance of lynching created enduring national and institutional woulds that have not yet healed. Lynchings occurred in the communities where African Americans today remain marginalized, disproportionately poor, overrepresented in prisons and jails, and underrepresented in decision-making roles in the criminal justice system.

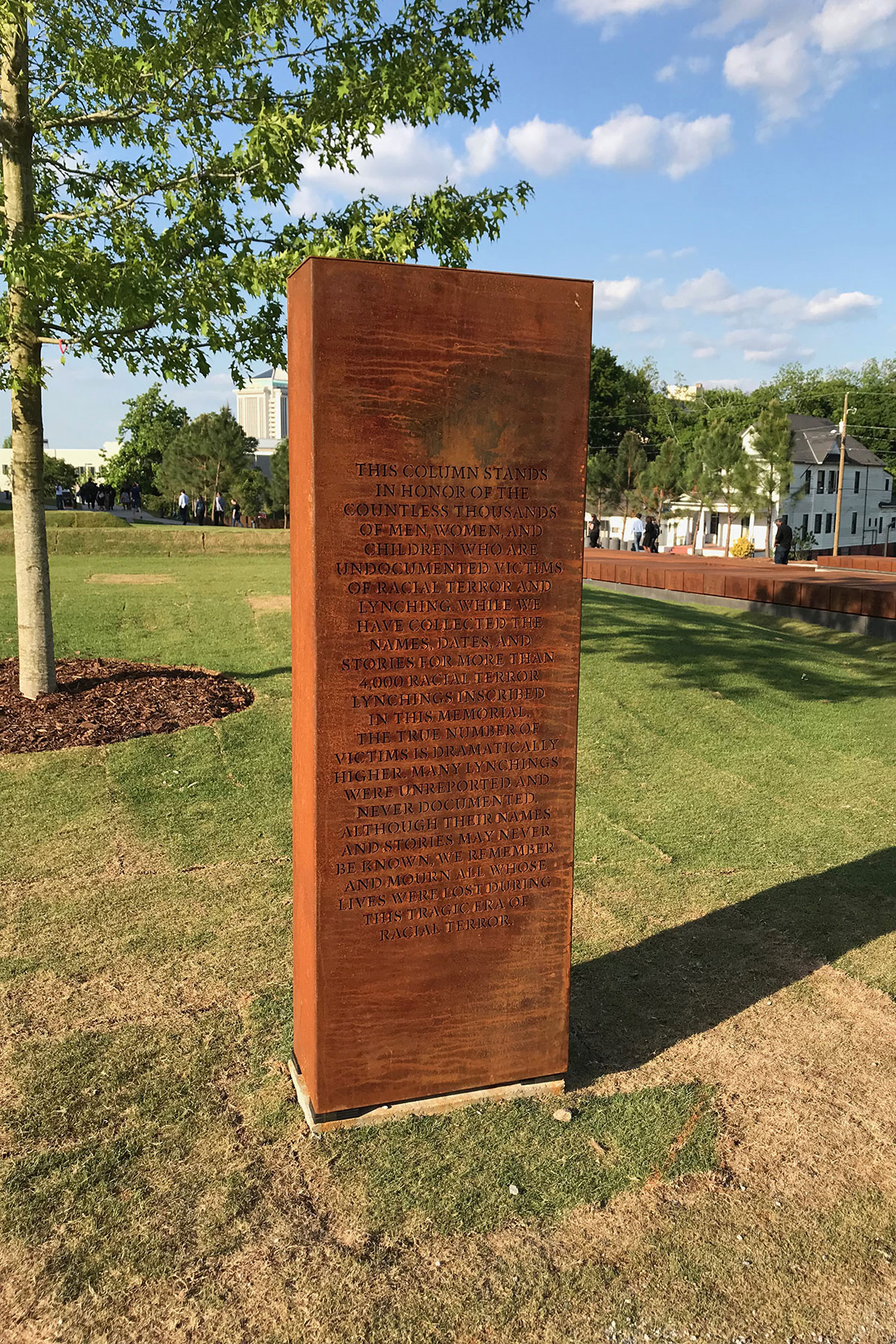

At this memorial, we remember the thousands killed, the generations of black people terrorized, and the legacy of suffering and injustice that haunts us still. We also remember the countless victims whose deaths were not recorded in news archives and cannot be documented, who are recognized solely in the mournful memories of those who loved them. We believe that telling the truth about the age of racial terror and reflecting together on this period and its legacy can lead to a more thoughtful and informed commitment to justice today. We hope this memorial will inspire individuals, communities, and this nation to claim our difficult history and commit to a just and peaceful future.”

– Inscription on marker at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice