Off the coast of Nagasaki, the second city to be devastated by an atomic bomb in World War II, lies a tiny island located along the southwestern island of Kyushu in Japan. From a distance, it appears to resemble the formidable silhouette of a naval warship cutting through the waves.

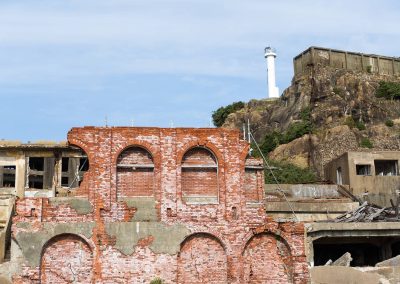

It is a place where crumbling cement apartment blocks stare out at the horizon, where silent corridors and dusty staircases trace the outlines of vanished lives. Officially known as Hashima Island, it is more commonly called Gunkanjima, which translates to “Battleship Island.”

In many ways, it is not just a relic of a bygone era. It is a time capsule, sealed off from humanity when the last inhabitants departed decades ago. It had been left to the unforgiving elements, and remained vacant of any visitors except ghosts from the past.

THE BIRTH OF GUNKANJIMA

Hashima Island’s transformation from an uninhabited rock into a cornerstone of Japan’s industrial revolution began in the early 19th century, when coal was discovered beneath its seabed. By the mid-1800s, Japan had recognized coal as an essential resource for fueling its ambitions of modernization.

In 1887, the Mitsubishi Corporation acquired the island and began large-scale mining operations. To maximize the extraction of undersea coal seams, Mitsubishi expanded the island through extensive land reclamation, creating the fortress-like appearance that earned it the nickname “Battleship Island.”

Over the following decades, Gunkanjima became a thriving microcosm of industrial Japan, with tightly packed residential complexes, schools, and even leisure facilities built to accommodate the growing workforce. Those early developments laid the foundation for what would become one of the most densely populated places on Earth during its peak.

A HISTORY OF FORCED LABOR

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 marked a turning point in Japanese history, ending centuries of feudal rule under the Tokugawa Shogunate and returning power to the Emperor. The political revolution sparked a rapid modernization campaign as Japan sought to catch up with Western industrial powers.

The new government adopted sweeping reforms, abolishing the rigid class system and promoting industrial growth through expanding infrastructure, technology imports, and state-backed enterprises. During that period, coal became a crucial resource for fueling industrialization, powering steel production, railways, and naval expansion.

For decades, coal from Gunkanjima fueled steel mills and powered shipyards that helped put Japan at the forefront of modern industry. Expanding markets and the demands of a growing economy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries rendered the site a symbol of rapid transformation. Like other heavy industries of the period, the transition from a largely agrarian society to an industrial one caused waves of social and economic change.

With a peak population reaching several thousand in a span of barely one square kilometer, Hashima Island was once one of the most densely populated places on Earth. Imperial expansion and war would only intensify production demands and drive the need for labor.

During that period, forced labor became a mechanism to ensure a steady workforce. Individuals from the Korean Peninsula were brought to Japan against their will to support coal mining and other strategic industries that required intensive and often dangerous labor.

Japan had annexed Korea in 1910, establishing it as a colony under harsh and exploitative rule. Koreans were treated as second-class citizens, often regarded as inferior or subhuman, and subjected to systemic discrimination in every aspect of society.

The dehumanizing view of Koreans was deeply ingrained in the systems that governed their lives during Japan’s Colonial rule, extending into the labor practices imposed on them. When Japan’s war effort intensified in the 1930s and 1940s, that discriminatory ideology justified the conscription of Koreans into dangerous and grueling work environments.

Many were forcibly relocated to industrial sites in Japan, like Gunkanjima. Conditions at its mines were daunting, even for voluntary Japanese workers. An unfamiliar language, cramped quarters, and a rigid hierarchy shaped the everyday experience of indentured Koreans. Those forced into labor often faced grueling shifts, limited rations, and the constant risk of industrial accidents.

Most held little hope of escaping their plight. Gunkanjima’s isolation by sea, as well as strict oversight by guards and employers, meant that leaving was almost impossible. Oral histories compiled in later years mention hardships that have left emotional scars for generations on the descendants of those who survived.

ABANDONMENT AND ISOLATION

In the post-war years, after the peak of coal mining, Japan changed its national energy policies in a shift toward imported oil. Domestic coal production declined, and Gunkanjima’s mine became less profitable. The enormous cost of maintaining living spaces and infrastructure in such a harsh marine environment grew difficult to maintain.

The end of Hashima Island’s inhabited life came swiftly and decisively, and many years after Japan’s defeat in WWII. In 1974, the Mitsubishi Corporation, which had managed its coal mine for nearly a century, announced its closure. By then, Japan’s energy policies had shifted away from coal to cheaper imported oil, rendering operations on Gunkanjima economically unfeasible.

With little warning, residents were given just weeks to pack their belongings and leave the island for good. When the final ferry departed, Hashima’s densely packed apartments, schoolrooms, and communal spaces were left eerily intact, creating a post-apocalyptic scene that would remain undisturbed for decades.

For nearly 35 years, Gunkanjima remained completely off-limits, an isolated ruin battered by typhoons and the harsh salt air of the East China Sea. That period of abandonment earned it a new nickname as a “ghost island,” shrouded in mystery and cut off from the public. The restricted access and safety concerns further deepened its obscurity.

Administrative control of the island was transferred to the city of Nagasaki. With a national focus on innovating technology that would propel Japan into an economic superpower in the 1980s, Gunkanjima was considered an inconvenient relic of Japan’s wartime industrial past. Time and indifference would eventually render it unsafe for exploration.

Concrete walls crumbled under the strain of repeated storms, while rebar exposed to the elements gradually corroded. Most of the buildings that remained standing became hollow shells, reflecting the lost ambition of another era.

THE RISE OF HERITAGE TOURISM

Gunkanjima’s silhouette would eventually become an object of curiosity to foreigners visiting Nagasaki at the dawn of the Internet. The island was visible from shore, but as unreachable as it was not talked about.

It was not until urban explorers, known as haikyo-sha, began taking photos to document the island’s decaying structures was the curtain of secrecy finally pulled back. Sneaking onto Gunkanjima in small boats, those early visitors risked arrest and personal injury as they navigated through crumbling stairwells, hollowed-out classrooms, and collapsing apartments.

The images they captured were shared with niche communities online, years before mobile devices like the iPhone ushered in the era of influencers with Instagram, TikTok, and other social media sites.

In those early days of the Internet, visits were often carried out in secrecy under the cover of night to avoid detection. But as the trickle of photos began to circulate over the years, they helped to reawaken public interest in the island’s forgotten past. The haunting images of a place frozen in time sparked fascination from historians, and appealed to photographers and adventurers who were attracted to sites of urban decay.

Over time, Gunkanjima’s allure grew and the Japanese government began receiving proposals to formally reopen the site. In 2009, following extensive safety assessments and the construction of limited walkways for visitors, the island officially opened to guided tours. The shift from obscurity to public spectacle marked the beginning of Gunkanjima’s transformation into a tourist destination.

Visitors today can board ferry tours from Nagasaki to step briefly onto the island’s southern edge. Though access remains restricted to prevent accidents in its hazardous interiors, tourists flock from all over the world to catch a glimpse of the iconic ruins. In recent years the site has served as a backdrop for documentaries, films, and even pop culture phenomena like the James Bond movie “Skyfall.”

Gunkanjima’s hauntingly preserved ruins are unique, but have parallels in industrial sites around the world. One popular example could be found in Milwaukee. Like Gunkanjima, the Solvay Coke Factory was once a symbol of industrial progress, playing a key role in coal gas production and steelmaking during the height of Milwaukee’s manufacturing era.

Both sites reflected the rise and fall of vital industries, yet their paths after abandonment diverged sharply. Gunkanjima, isolated by the sea, remained untouched for decades, preserving its eerie time-capsule quality. By contrast, the Solvay Coke Factory, located within an urban environment, succumbed to encroachment, vandalism, and partial demolition, leaving behind only fragments of its once-thriving infrastructure.

The “rediscovery” of Gunkanjima invigorated the local economy around Nagasaki, but it also reignited debates about how to responsibly preserve and present its history, both as a marvel of industrial ambition and as a site of forced labor and human suffering.

THE UNESCO CONTROVERSY AND NATIONAL PRIDE

The island became part of a group of former factories, shipyards, and mines proposed for recognition as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. It was a national effort to highlight Japan’s modernization between the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Being conferred that status would significantly boost tourism, bolstering regional economies that have languished amid Japan’s deindustrialization.

But the bid for that level of recognition has been marked by protests and controversies. Critics point out that confining the heritage timeline to the Meiji era excluded examining the full spectrum of events that occurred on the island, and at similar facilities like the Sado gold mine.

> READ: Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

Korean forced labor survivors of Gunkanjima and their families have sought legal redress for years, noting that existing companies today from that era like Mitsubishi, have continued to profit from their brand names and infrastructure. That revenue was originally built during times when forced labor was part of their daily business operations.

Though treaties were signed between Japan and South Korea to normalize diplomatic relations, war reparations were made within the framework of state-to-state agreements, often bypassing direct compensation to individuals.

Compensation settlements over decades have remained entangled in the complexities of legal responsibility and moral restitution. Each new lawsuit or diplomatic discussion stirs memories of an unresolved past that remains unsettled to this day.

Supporters of World Heritage status view Gunkanjima and related sites and argue that they are testaments to Japan’s ingenuity and worth of both preservation and recognition. Skeptics and critics contend that any commemorative plaque or museum exhibit should not omit or downplay the stories of forced labor. They oppose what they see as selective storytelling and caution that ignoring historical injustices risks perpetuating unresolved tensions.

THE CHALLENGING PATH FORWARD

Gunkanjima poses a question that resonates far beyond Japanese shores, how should a society handle heritage sites that are stained by injustice? Around the globe, monuments and memorials continue to spark controversy when they become rallying points for unresolved historical debates.

Contemporary Japanese society is not monolithic in its understanding or commemoration of Gunkanjima. Some individuals and organizations have actively worked to uncover historical documents, collect oral testimonies, and incorporate them into educational materials.

Municipal authorities and tourism bureaus face the challenge of presenting a balanced perspective while catering to visitors’ expectations for what has become an Instagram destination. Despite such complications, the island’s status as a haunted landmark has not faded, and only grown since the COVID-19 pandemic.

If there is a path forward, it lies in grappling with the many contradictions. Some proposals say that the best method is to establish comprehensive cultural and historical centers near the island, so that visitors can learn about every layer of its story.

Others propose that any UNESCO-associated acknowledgment should include a mandate to detail the experiences of forced laborers clearly and unapologetically. Such approaches would neither erase nor overly sensationalize Japan’s past. Rather, they would offer a respectful and unvarnished tribute to the island’s historical significance, in all its complexity.

In its ghostly silence, Gunkanjima continues to speak volumes. It tells of the frantic scramble toward industrial might, the fortunes made and lost, the lives built in the shadow of towering apartment blocks, and the struggles of those compelled to work in an undersea mine.

Trapped between the rising tide and the unstoppable decay of abandoned concrete, Gunkanjima is frozen in time. Yet its memory remains at the center of discussions about accountability and how to present history. It stands as a cautionary monument, both to the triumphs of human engineering and to the deep scars left by coercion and war.

© Photo

Eugene Hoshiko (AP), and A. Kiri, Andylai, Enken, Fafo, Grass Flowerhead, Haloy, James Davies, Jef Wodniack, Journeykei, Kamatari, Kelly Lam, Khaidon, Kou2341, Leung Chopan, Linegold, Luc4, Masakichi, Miyake, Panparinda, Piti Tan, Raicho, Ryoheim91, Sean Pavone, Setsuna0410, Shamit Dasgupta, Shunskee, Sitthinart Susevi, Toshiyuki Ookubo, Vadim Ozz, Y.S. Graphic, Yanchi1984, Ziggy Mars, 9Ensa10 (via Shutterstock)