“You’re Agent Hoffman, of German extraction? My name is Donovan, Irish, both sides, mother and father. I’m Irish. You’re German. But what makes us both Americans? Just one thing. One. One. One. The rulebook. We call it the Constitution, and we agree to the rules, and that’s what makes us Americans. It’s all that makes us American. So don’t tell me there’s no rulebook.” – Tom Hanks (as James B. Donovan), “Bridge of Spies” (2015)

During the height of the Cold War, America extended its most sacred constitutional protections to a man who had been operating as an enemy agent. Rudolf Abel, the Soviet intelligence officer captured in New York and charged with espionage, did not disappear into some clandestine detention site.

He was not stripped of legal representation, nor denied a fair trial. Instead, Abel was defended in court by Brooklyn lawyer James B. Donovan, who stood not to excuse Abel’s mission, but to defend the very notion of American justice — due process for all, even enemies.

That ideal now stands in stark contrast to the case of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Salvadoran national who was apprehended by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and later deported without trial, indictment, or access to counsel, following unsubstantiated claims of terrorism ties.

While the Trump regime has not presented publicly verifiable charges, the expulsion — followed by El Salvador’s refusal to return him — places Garcia in a legal vacuum, outside U.S. jurisdiction, stripped of rights but never convicted. Trump has effectively created a system to dispose of his enemies without any barriers to stop him, or any measure to correct his arbitrary injustice.

On April 14, the president of El Salvador Nayib Bukele met with Trump and confirmed his government would not return Garcia back to the United States, saying there was no basis for the small Central American nation to return a Maryland man who was wrongly deported.

“The question is preposterous. How can I smuggle a terrorist into the United States?” Bukele, seated alongside Trump, told reporters in the Oval Office. “I don’t have the power to return him to the United States.”

The United States, having removed Garcia without trial, created a paradox on purpose. It cannot formally request extradition for a person it never charged. It cannot claim the legitimacy of its legal process because none was followed. And it cannot compel cooperation from El Salvador without acknowledging the very violation it committed.

This is the impossible legal trap that now defines the case: a man the United States treated as an accused criminal, but never as a defendant, has effectively vanished into sovereign limbo. No trial. No conviction. No appeal. And no mechanism to bring him back into the legal system, because he was never properly processed by it in the first place.

Critics argue this is more than a bureaucratic failure, it is an abandonment of basic constitutional principles.

“We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty. We must remember always that accusation is not proof and that conviction depends upon evidence and due process of law. We will not walk in fear, one of another. We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason. If we dig deep in our history and our doctrine, and remember that we are not descended from fearful men, not from men who feared to write, to speak, to associate, and to defend causes that were, for the moment, unpopular.” — Edward R. Murrow,

What makes Garcia’s case more alarming to civil liberties advocates is how unremarkable it has become. In the years since 9/11, the machinery of American law enforcement has increasingly operated through informal detentions, classified watchlists, and opaque legal theories that rely on executive discretion rather than judicial scrutiny.

With no trial on the record, no indictment presented, and no court decision to review, Garcia’s expulsion cannot be challenged — by him or anyone else. That means the United States cannot legally demand his return. And El Salvador has now refused to participate in a process to bring justice, because it profits from being an accomplice to Trump’s crime and the process of injustice.

In the movie “Bridge of Spies,” Donovan’s insistence that Abel be granted a fair trial was not about exoneration — it was about identity. What does it mean to be American, he argued, if we discard the very rulebook that defines our national compact?

Rudolf Abel was tried under full legal process, and his exchange for Francis Gary Powers took place under clear rules of law and diplomacy. In contrast, Garcia’s case exposes a modern American state that appears willing to forgo legal clarity in favor of toxic political expedience — with consequences far beyond this one man.

What happens when a country discards the very procedures that make its power legitimate? When due process is treated not as a right, but a luxury? Garcia’s case provides a grim answer: the emergence of a legal black hole, one that any citizen or non-citizen could fall into, without recourse, and without visibility.

Unlike the high-profile detentions at Guantánamo Bay, which sparked international debate and litigation, Garcia’s situation unfolded quietly. No courtroom arguments. No press conferences. No visible paperwork. Just the silent machinery of administrative power, and the near-total absence of accountability. That silence, legal scholars argue, is precisely what makes it so dangerous.

“The due process clause, properly construed, prohibits arbitrary government action, particularly that which unjustifiably restricts individuals’ liberties. There are implicit limits on government power, limits inherent in the idea of law. As Sandefur says, a legislative act that fails the tests of generality, regularity, fairness and rationality (being a cost-efficient means to a legitimate end) is not a law, so enforcing it cannot be due process of law. The Constitution guarantees government that secures individual rights by establishing lawful, meaning non-arbitrary, rule. So, in determining whether there has been due process, a court must examine not just the form of a statute or the procedural formalities that produced it, but also its substance. Again, ‘the Constitution does not require just any process but due process.’ Were ‘due’ simply a synonym for ‘democratic,’ the due process guarantee would guarantee nothing.” – George Will Ph.D., Author and Columnist

If the rulebook can be closed at will, then there is no meaningful distinction between democratic process and authoritarian decree. And yet, the lack of public outrage has underscored how normalized such exceptionalism has become. Civil liberties organizations have called attention to Garcia’s case in recent weeks, but there has been no congressional inquiry, no oversight hearing, and no confirmation from the Department of Homeland Security on what specific accusations, if any prompted his removal.

The contradiction could not be clearer: Rudolf Abel was a confirmed Soviet agent during one of the tensest moments in global geopolitics. Yet he was granted an open trial in a U.S. court, defended vigorously, and later exchanged through a formal, lawful diplomatic channel. Garcia, whose alleged ties to terrorism have never been publicly substantiated, was removed by executive order, in secret, and cast into an unresolved international standoff.

That standoff is now an object lesson in the consequences of procedural decay. This is not simply a matter of international politics. It is a domestic indictment, a warning about what it means when process, precedent, and accountability are eroded by executive convenience. Trump’s America has, in this case, constructed a prison without walls. A person without rights, held nowhere, belonging to no system of justice, denied access to both guilt and innocence.

The Constitution does not offer selective protection. It does not require citizenship to guarantee due process. And it does not permit shortcutting rights in the name of national security. If Garcia can be removed and abandoned without trial, then so can others — citizens, residents, or visitors — depending only on the opacity of executive discretion.

As Trump and Republican allies continue to expand the use of unilateral enforcement powers, the scope of such a black hole is growing. Civil liberties attorneys point to a rise in expedited removals, classified watchlists, and extrajudicial deportations as evidence of a systemic trend.

If the rulebook is discarded, what remains? In “Bridge of Spies,” Donovan’s invocation of the Constitution was not symbolic — it was legal, moral, and national. “That’s what makes us Americans,” he declared. Not flags. Not anthems. Not security. The rulebook.

Americans have fought and died for that rulebook. Not for a party. Not for a corrupt and criminally convicted president. For the right to be governed by laws, not by the arbitrary will of those in power. To erase that foundation is to betray the very essence of the country.

Garcia is the embodiment of a systemic failure — and a national test. If Americans cannot be troubled by the denial of rights, cannot be moved by the evaporation of legal accountability, then what remains of the claim to moral authority?

Patriotism without principle is not patriotism. It is obedience to a cult, not democracy. It is feudalism draped in red, white, and blue.

The bridge where Abel and Powers were exchanged was never a symbol of justice, it was a point of pragmatic necessity, where governments traded bodies to preserve political advantage. Today, there is no such bridge for those abandoned by their own country’s legal system. The question that remains is whether Americans will even notice, or worse, whether they still care.

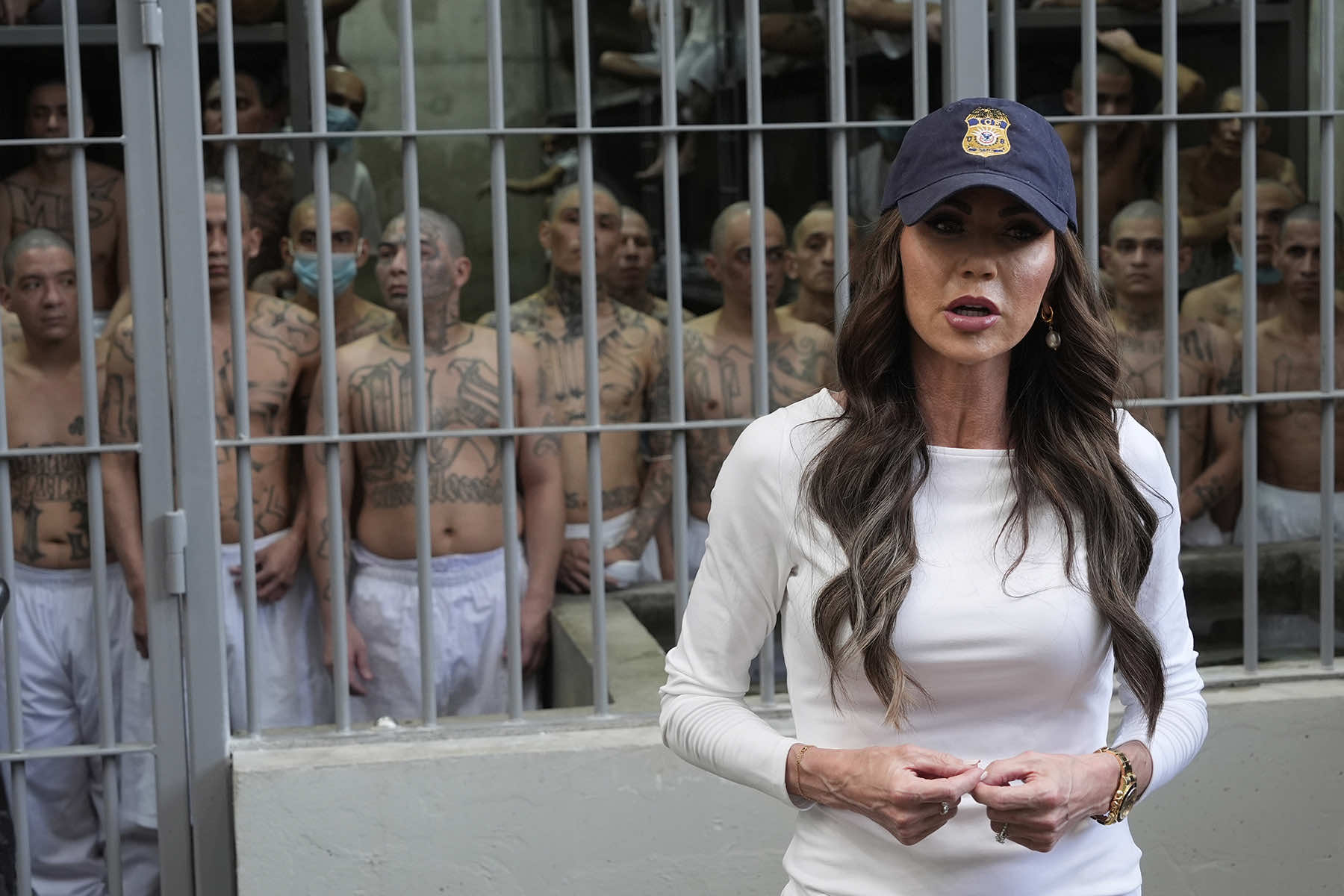

© Photo

Touchstone Pictures, Alex Brandon (AP), and Jose Luis Magana (AP)