“The horrors that are due to race prejudice come home to the Jew more forcefully than to others of the white race, on account of the centuries of persecution that they have suffered and still suffer.” – Julius Rosenwald

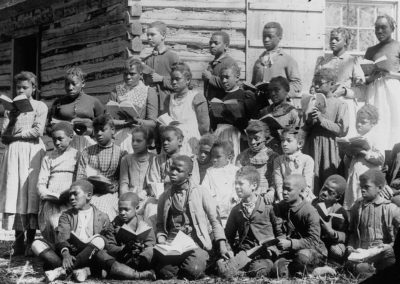

Between 1912 and 1932, nearly 5,000 Rosenwald schools for black children were established in the South. They were built in the eleven states of the Confederacy as well as Oklahoma, Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland. They ranged in size from simple single-teacher schools to large high schools.

Julius Rosenwald, Sears Company Head and Jewish Philanthropist

They were called “Rosenwald schools,” because the money to start them came from Julius Rosenwald (1862-1932). He was a second-generation American. His parents emigrated from Germany in 1854 to escape anti-Jewish discrimination. Rosenwald made a great fortune by building Sears, Roebuck & Company into the world’s largest retail company. He served as Sears President and Chairman.

Famed Black Educator, Booker T. Washington

Equally important in building the Rosenwald schools was Booker T. Washington (1856-1915). He was born a slave in Virginia. At age 25, Washington became the first principal of the Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers in Alabama. He built it into the Tuskegee Institute, the largest and most successful college for African Americans, now called Tuskegee University. By the early 1900s, Washington was the most prominent and powerful African American in the country.

A Life-Long Partnership

Julius Rosenwald (“J.R.”) and Booker T. Washington formed an extremely fruitful and important lifelong collaboration. Rosenwald, son of German-Jewish immigrants, rose to become one of the wealthiest men in America as well as a beloved humanitarian who gave away -in today’s dollars – the equivalent of $630 million dollars. Booker T. Washington, born into slavery, overcame great obstacles to obtain an education, eventually becoming the most prominent of Negro educators, powerful orator and fundraiser, and builder of the esteemed Tuskegee Institute.

Washington and Rosenwald first met in 1911. Rosenwald and his wife traveled to visit Tuskegee Institute later that year. A month later, Rosenwald joined the Board of Directors of Tuskegee. He remained on the board for the rest of his life.

Rosenwald had money. Washington had knowledge and contacts. In 1912, the two agreed to work together to construct public schools for black students. They first decided to create six schools near Tuskegee as a pilot project. Over the years, the number of schools grew and spread through the entire South.

A Dedication to Quality

Schools were designed with the health, well-being, and educational needs of the children in mind. Even the schools’ placement on the land was thought out, to give maximum light and air. Blackboards formed moveable walls, there was outdoor space for physical education and recess, and often an industrial-type workshop where children learned practical manual skills.

All Rosenwald schools were built to specifications for size, ventilation, windows, and other properties. Tuskegee Institute architects developed the plans. Some schools were built by Tuskegee students. After Washington died, quality control suffered. Rosenwald then created the Rosenwald Fund to oversee school construction.

Self-Help Required

Rosenwald did not simply give money to people to build schools. He required people in each locality to show how much they wanted the school. They had to raise money or contribute labor. They also had to convince the local white government to contribute money.

Rosenwald actually provided the smallest amount of money: about $4.4 million. State and local governments gave over $18 million. Local people raised about $6 million – $4.7 million from blacks and $1.2 million from whites. (They contributed to Rosewald schools besides what they already paid in taxes for public schools.)

The Great Scope of the Work

By the time of Rosenwald’s death in 1932, about one-third of black students in the South were attending Rosenwald schools. In addition to 4,977 schools, Rosenwald contributed to 217 homes for teachers. He also established 163 machine shops where students learned practical skills. North Carolina had the most Rosenwald schools: 813.

Julius Rosenwald never finished high school, but he gave millions of dollars for education. He also gave a great deal of money to other causes, including Jewish charities. He was the main donor to establish the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago.

What Happened to the Rosenwald Schools

The 1954 Supreme Court order to integrate public schools meant that black students moved to white schools. Many Rosenwald schools were abandoned. Today, most have been destroyed or have fallen into disrepair – but some remain. In 2002, the National Trust for Historic Preservation listed the Rosenwald schools as “endangered places.” They now are used as schools, community centers, senior citizen centers, and museums. In June 2012, The National Trust held a conference, “100 Years of Pride, Progress and Preservation,” featuring education sessions, documentary films, tours, and national speakers.

What a powerful legacy they left – a wealthy Jewish businessman who believed in social justice and a former slave who believed in the power of education to uplift his brethren! Over six hundred thousand African Americans received good educations in Rosenwald elementary and high schools. Many went on to college and vocational training and made important contributions to community and country.

“In order to be successful in any undertaking, I think the main thing is for one to grow to the point where he completely forgets himself; that is, to lose himself in a great cause. In proportion as one loses himself in this way, in the same degree does he get the highest happiness out of his work.” ― Booker T. Washington

- Joyce Mallory: Jewish Refugee Scholars at Black Colleges

- Exhibit details partnership between Jews and Blacks in shared struggle for Civil Rights

- Rosenwald Schools and their legacy of Black-Jewish collaboration for Negro Education

- When Jews were neither white nor black but “some sort of colored folks”

Fran Kaplan, EdD

Virginia Historical Society and Fisk University

Portions originally published on America’s Black Holocaust Museum as The Rosenwald Schools: An Impressive Legacy of Black-Jewish Collaboration for Negro Education