“Very often I am asked why I feel so connected to the Chernobyl area, the answer is not always easy for me to be able to explain: I have always considered these men legendary, who in silence have worked for others. Courageous and admirable, in the critical and impossible situations in which they found themselves, they managed to manage honor, humanity and courage and there is no greater and more difficult undertaking than being able to manage these three things all together. And I always feel so small when I’m in the land of heroes, because the history of that place is nothing more than the biography of these great men. Everyone chooses their heroes.” – Francesca Dani

December 14 in Ukraine is a very important holiday, a “day in honor of the participants in the liquidation of the consequences of the accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant,” it is simply celebrated as “the day of the liquidator.” In the former Soviet Union on April 26, 1986, at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant – which was located in the territory of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, the greatest technological catastrophe occurred in the history of humanity. Thanks to the dedication and courage of military, civilians, reservists, volunteers, doctors – Men and women from all over the former USSR – the accident was localized and in the shortest possible time. These liquidators had a long and dangerous job that lasted from 1986 to 1989. But many of these men paid with their health, and also with their life.

“I listened to the stories of the heroes who lived what Chernobyl was on their skin, of those who still carry the weight on their shoulders, I saw with my eyes that human sphere that I wanted to know and I understood that to unite the hearts of people is not only the harmony of their feelings but very often it is also their fragility.”

– Francesca Dani

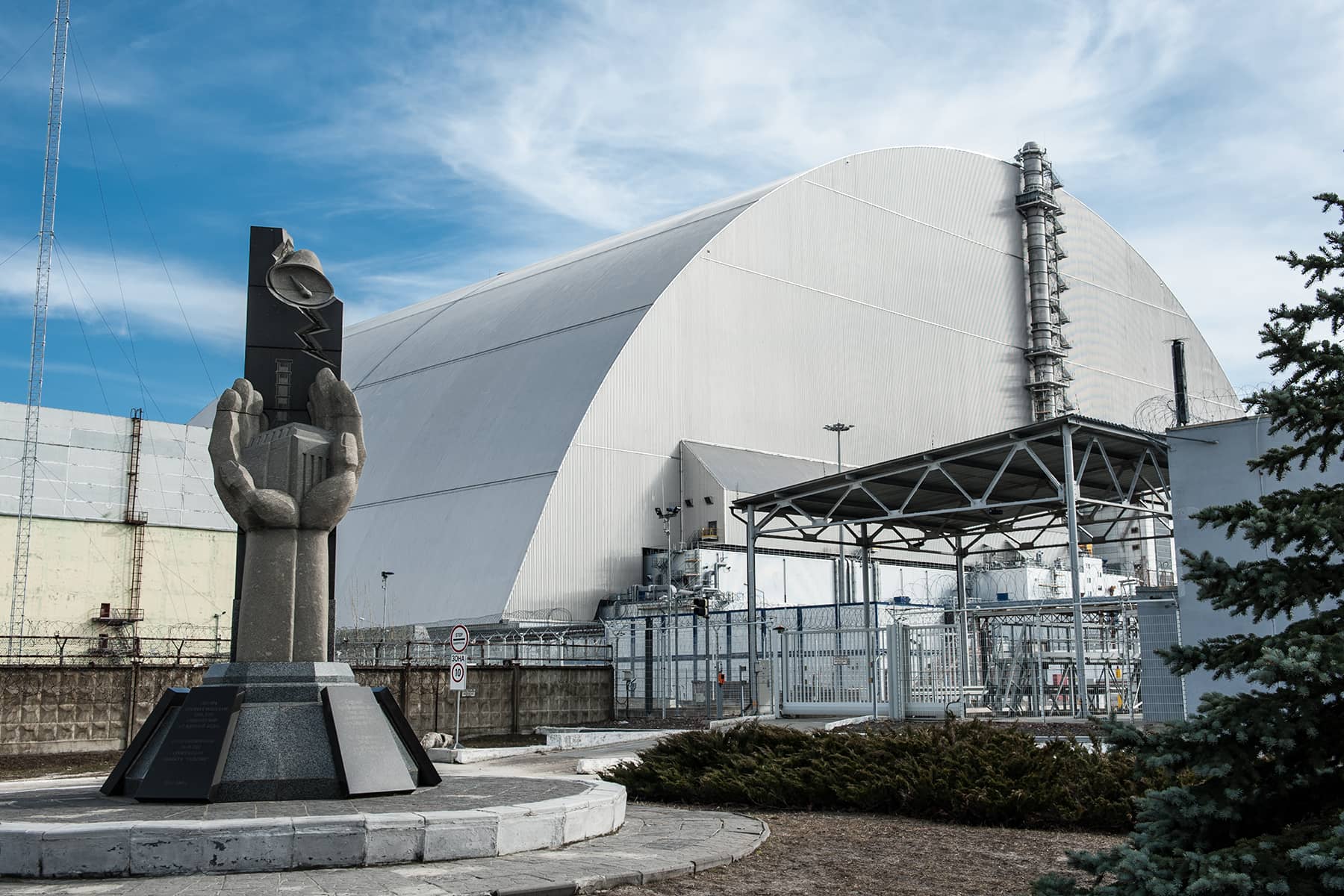

On November 30, 1986, after 206 days of construction the “sarcophagus” was completed, an insulating structure built immediately after the explosion of the fourth reactor. It was positioned as a protective envelope above the destroyed reactor, and served to protect the population from radiation. Two weeks later a communist newspaper called “Pravda” published and article concerning the completion of the work on the “sarcophagus.” The day of that article was December 14, 1986. That is why December 14 was chosen to establish a day in honor of the participants who worked at solving the accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. Commemorative ceremonies take place in Ukraine on December 14, reminding the public and the world of the tragedy, and of incredible heroes who saved millions of lives by sacrificing theirs.

“Heroes are born from every tragedy and all the liquidators were the real protagonists of this story, they went to meet danger with primitive precautions on them but without holding back. Humanity has changed and now it is not always easy to accept and understand such heroism, more like a sacrifice. Perhaps it is precisely for this reason that there is still too little talk of it.” – Francesca Dani

Francesca Dani is a professional freelance journalist, specializing in photography of abandoned settlements within the Chernobyl “exclusion zone.” She is also creator of the cultural project “Chernobyl Synopsis: lights and shadows of Chernobyl,” which promotes educational information on the disaster and its aftermath.

Milka Ivanova and Dorina-Maria Buda: Memories of living through Chernobyl and its consequences

We were five years old when the Chernobyl disaster happened. At the time, Milka was living in the small mountain town of Razlog in the People’s Republic of Bulgaria, about 1500 km away from the disaster area. Dorina was born and grew up in a small town in the Socialist Republic of Romania, approximately 850 km south of Chernobyl. Bulgaria and Romania were heavily contaminated by radioactive material from the explosion that blew the lid off reactor No. 4 at the Vladimir Ilyich Lenin Nuclear Power Plant – more commonly known as Chernobyl – in the town of Pripyat, at the time in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. While we were soon dubbed “the Chernobyl children”, the communist authorities kept Bulgarians and Romanians in the dark about the magnitude and implications of the explosion. It wasn’t until the Iron Curtain lifted that many of us would learn the truth.

Bulgaria, May Day 1986 – Milka Ivanova

As a Bulgarian, I don’t often think about Chernobyl, even though I study communist heritage tourism. Remembering the events of spring 1986 and my government’s mishandling of the crisis still makes me angry, but I try to maintain some emotional separation from my research. When the HBO miniseries Chernobyl aired, I expected the buzz it generated would renew public interest in visiting Chernobyl, and interest in the communist past in general. What I did not expect was to relive my recollection of the days after the disaster.

Both the Soviet and Bulgarian governments kept quiet, even while Western news agencies reported the disaster on April 26 1986. The first official announcement within the Soviet Union came on the evening of the 28th. In Bulgaria, the first brief announcement came three days after the explosion on April 29.

I don’t remember much about the announcement itself or the general reaction in Bulgaria. What I remember is my grandmother getting a phone call from her brother, who had connections to the upper echelons of the Bulgarian Communist Party. He warned her not to give five-year-old me any milk to drink. He gave no reason, and my family didn’t know what to make of it. I remember that the Labour Day parades went ahead as usual and that all the children in my home town had to attend. We were all marching in radioactive rain.

Once the Communist Party admitted there had been an incident at the Chernobyl nuclear plant, they reassured the Bulgarian people that things were under control and that radiation in the atmosphere and food was below dangerous levels. At the same time, the leaders of the Bulgarian Communist party were eating and drinking imported food and water.

ON THE ROMANIA-UKRAINE BORDER – Dorina-Maria Buda

I grew up in Romania – another child of the Chernobyl generation. Still, Chernobyl rarely invaded my thoughts – though the memories are there now, churning in the back of my mind. There’s a certain inner revulsion to most political events from those times for me. I haven’t watched the new miniseries and I’m unlikely to revive some of the personal and collective trauma by doing so.

In 1986, my father was a captain in the Romanian army, patrolling the border with the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. He remembers the army were on high alert in the months after the blast and they were asked to collect information from truck drivers crossing the border, to understand the unfolding situation around the disaster area.

At the same time, the army increased the intensity of their chemical training for soldiers and officers and were given courses on how to better understand and prepare for biochemical attacks. My mother was told to avoid lying in the sun, or risk burning her skin. Only later did she realize that radioactive fallout was the real concern.

When I wrote this in 2019 – decompressing my memories and digging up those of my family back in Romania – there was still a heaviness in my chest. Milka and I channeled our anxieties over Chernobyl and life in communist eastern Europe into our research.

To overcome the restraints of those days, I have travelled, worked and studied in eight countries on four continents. My published work deals with psychoanalytic theories of the death instinct, trauma and nuclear tourism – the industry that monetizes a fascination to visit places where nuclear accidents have laid waste to people and their communities. The Fukushima disaster of March 2011 in Japan created the most recent entry in this list of tourist hotspots.

Interestingly, 2011 was also the year that Chernobyl was officially declared a tourist attraction. The HBO miniseries has generated interest in nuclear tourism, but this fascination with our communist history is nothing new among western tourists. There is an understandable desire among people in eastern Europe to distance ourselves from our difficult – even traumatic – past, but Chernobyl’s heritage, like most communist heritage, is as much about the past as it is about the future.

The HBO miniseries no doubt illuminates the cover-ups and information blackouts that characterized the early response to the nuclear disaster. The events of April 1986 warn us about the cost of lies and of what happens when regimes distort the truth to preserve their grasp on power. In today’s climate of fake news, deceit and dishonesty, Chernobyl remains a lesson from which there is still sadly much to be learnt.

Milka Ivanova, Dorina-Maria Buda, Francesca Dani, Charlie Tango, and MI Staff

Torsten Pursche, Milosz Maslanka, Belikova Oksana, Olga Vladimirova, EvrenK alinbacak, Kirill Sergeev, Roman Belogorodov, Diego Grandi, Viacheslav Petrusha, James Kerwin, Tomasz Jocz, K. Budzynski, Fotokon, Roberts Vicups, Meunierd, Cristian Lipovan, and Pe3k (Shutterstock)