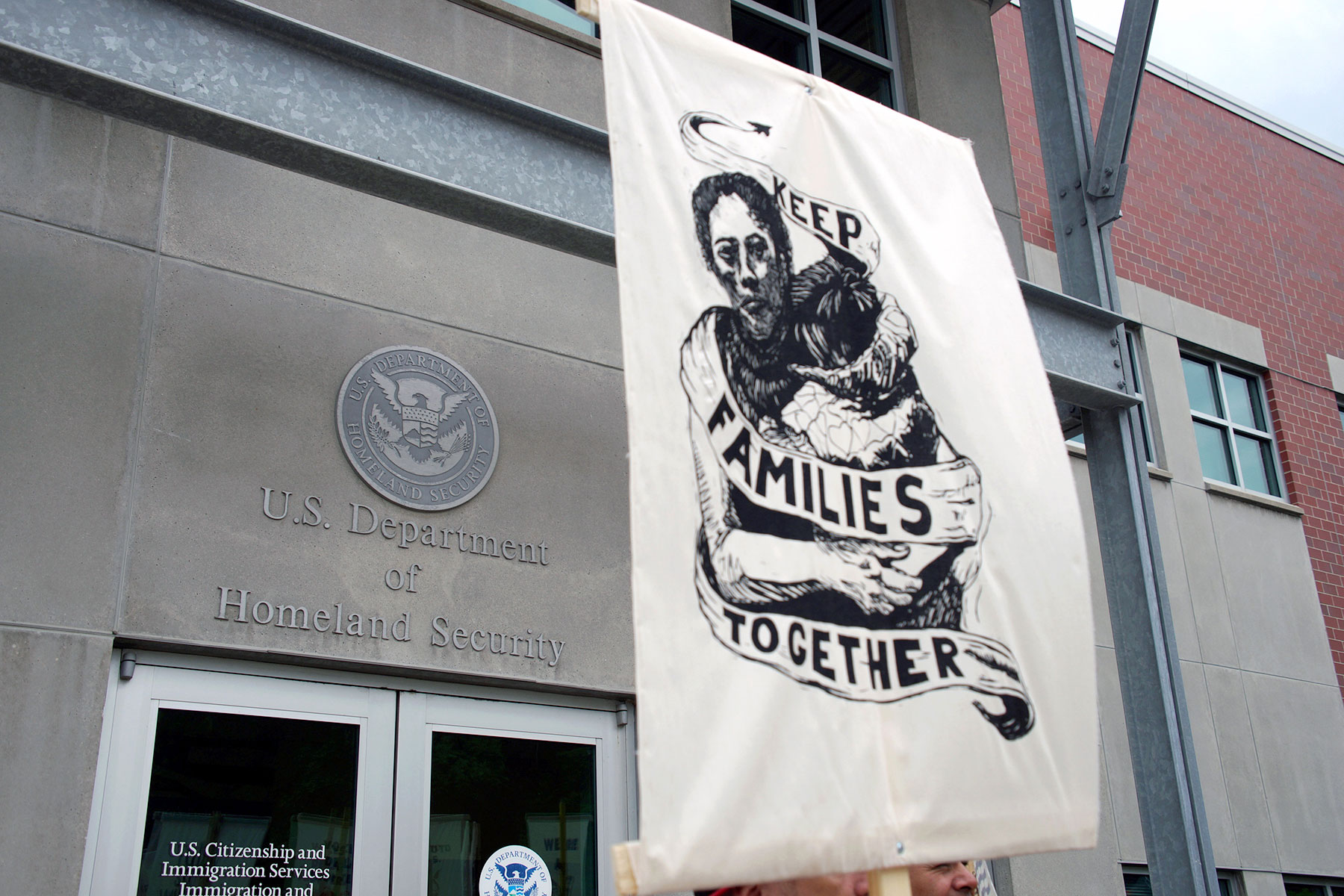

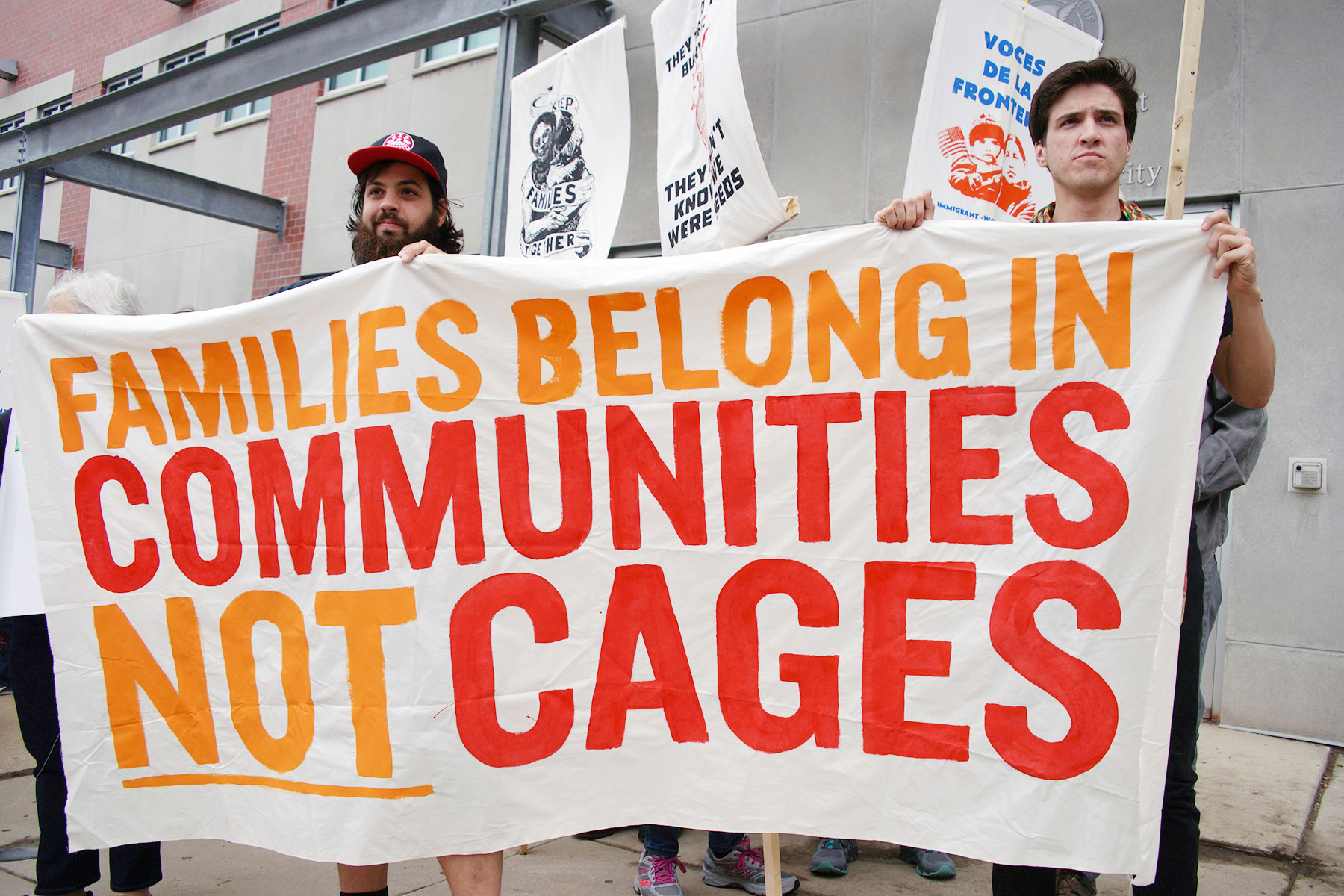

With nearly 2,000 immigrant children separated from their parents in just six weeks alone, there is an unprecedented human rights disaster unfolding at our border. As public outrage mounts, members of Congress demand access to government-run facilities, and the United Nations condemns us, the Trump administration is attempting to shift the blame — fast.

In the past week, the administration has made several misleading statements, trying to justify the systematic separation of children from their parents. On Monday, DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen held a press briefing where she doubled down on family separation, denying that the separation of children from their parents amounts to child abuse because, “We give them medical care. There’s videos; There’s TVs.”

All the while, horror stories are emerging: among them, Marco Antonio Muñoz, a Honduran father, who killed himself after being separated from his wife and child; three siblings taken from their parents who were told that they couldn’t hug each other in the shelter they were placed in; and parents who were deported four months ago and are still waiting for the U.S. to return their baby.

The level of cruelty is difficult to comprehend, and that’s how the administration wants it. Here’s what you need to know to understand family separation.

Is there a law that requires family separation?

Donald Trump has repeatedly blamed family separation on a law enacted by Democrats. On June 15, he told reporters, “I hate the children being taken away,” and added, “The Democrats have to change their law — that’s their law.” Secretary Nielsen repeated this falsehood at a briefing on Monday saying, “Surely it is the beginning of the unraveling of democracy when the body who makes the laws, instead of changing them, tells the enforcement body not to enforce the law.”

There is no law that requires the Trump administration to separate families.

This crisis stems from a series of policy choices the Trump administration made. In fact, reports arose as early as December 2017 that the administration was considering a plan to separate border-crossing parents from their children. In March, then-DHS Secretary John Kelly confirmed this, saying it would help deter Central Americans from coming to the United States.

Do the courts require family separation?

Absolutely not — despite the claims of GOP leadership to the contrary. Both House Speaker Paul Ryan and Senator Chuck Grassley have blamed family separation on the courts, specifically a decades-old court agreement (known as the Flores settlement) which established protections for children to prevent their indefinite detention in unlicensed facilities.

Getting rid of the protections in the Flores settlement would only further the administration’s goal of being able to indefinitely imprison families. But ending family separation doesn’t require family prisons. The Trump administration knows full well that alternatives exist — because it went out of its way to sabotage them.

In June 2017, the administration ended the Family Case Management Program, which allowed families to be placed into a program, together, that connected them with a case manager and legal orientation that ensured they understood how to apply for asylum and attend immigration court proceedings.

The program had a 99.6% appearance rate at immigration court hearings for those enrolled in the program. It’s not only a more humane alternative to family prisons; it is far less costly for taxpayers.

Despite that success, the administration chose to end this program only a few months after it was first reported that Kelly, then-Secretary of Homeland Security, was considering family separation as a deterrent strategy.

Does Paul Ryan’s bill end family separation?

This week House Republicans will vote on a bill that purports to protect Dreamers and end family separation but does neither. Known as the Border Security and Immigration Reform Act of 2018, the bill would put DACA-eligible individuals on a long and convoluted path to citizenship — which is all subject to whether Trump gets his border wall. The changes in the bill would make it harder to apply for asylum and includes dangerous provisions making it easier to jail children and families.

The bill would not do anything to stop Sessions’ zero-tolerance prosecutions — which is the main driver of family separation.

Is the administration separating asylum-seeking families who enter at ports of entry?

Yes, despite claims to the contrary. On June 17, DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen took to Twitter to defend family separation, saying, “For those seeking asylum at ports of entry, we have continued the policy from previous administrations and will only separate if the child is in danger, there is no custodial relationship between ‘family’ members, or if the adult has broken a law.”

In case Secretary Nielsen forgot, she’s currently a defendant in our class action lawsuit, where we represent families who entered at ports of entry to seek asylum and had their children taken away.

Ms. L, a Congolese mother who sought asylum at a port of entry, had her seven-year-old daughter taken away from her for fourth months. Immigration authorities made no meaningful attempt to verify their relationship during that time, only doing so after the ACLU filed its lawsuit.

Mirian G, a mother from Honduras, came to the U.S. with her young son on Feb. 20, 2018. She presented herself to immigration authorities and sought asylum, committing no crime. During her interview, Mirian provided immigration officers with several identification documents for her child which listed her as his mother. The next morning, Border Patrol agents took away her 18-month-old son with no explanation. She did not see him again for two months.

What is happening to people who cross the border between ports of entry?

On April 6, Attorney General Jeff Sessions instructed all U.S. Attorney’s Offices along the southwest border to adopt a new policy of “zero-tolerance” for illegal entry into the United States. On May 7, Sessions announced that the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security would partner together to prosecute anyone who crosses the border between U.S. ports of entry.

As Sessions put it, “If you don’t want your child to be separated, then don’t bring them across the border illegally.” Crossing the border without proper documentation is a misdemeanor that typically carries the penalty of a few days in jail if you’re prosecuted.

Here’s what the attorney general failed to mention: The government is not giving the kids back. Our client, Ms. C, experienced this firsthand. Ms. C, an asylum seeker, was separated from her 14-year old son after the government chose to prosecute for entering the country illegally. She served her time, but then had to wait eight months before her son was given back to her.

In addition, both Sessions and Nielsen are avoiding another crucial point — in several cities along the border, Customs and Border Protection officers have been turning asylum seekers away, telling them that the port of entry is at capacity. Members of Congress who traveled to the border met asylum seekers who experienced just that. Secretary Nielsen spun this as well, saying that asylum seekers are not being turned away per se, they are being told come back later.

Who can end family separation?

The Trump administration is choosing to separate families. It’s a policy decision that could be stopped at any time by the president without legislation.

The president’s own party has been vocal about his authority to stop this — from former First Lady Laura Bush to senior Republican Senators McCain, Murkowski, Collins, and Corker. In the words of Republican Senator Lindsay Graham, Trump can end this “with a phone call.”

Mr. President, make the call.

Amrit Cheng

Lее Μаtz and Center for Border Protection

Originally published by the ACUL as Fact-Checking Family Separation