More than seventy-five pieces of work were unveiled at the local creative arts festival, hosted by the Milwaukee Veterans Affairs as the first step toward the annual national competition.

Local veterans enrolled for care at the Milwaukee VA were eligible to participate in the festival competition, and top winners qualify to attend the National Veterans Creative Arts Festival in October, held in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

There were more than 32 categories in visual and performing arts, including painting, sculpture, photography, ceramics and leatherwork, dance, drama, and music.

The festival and competition offers veterans a creative platform for self-expression. Many use visual and performing arts as part of their healing from post-traumatic stress, depression, substance abuse, and other issues. Much of the art focuses on the process of healing. The national event includes workshops, with top artists displaying their work with others from across the nation.

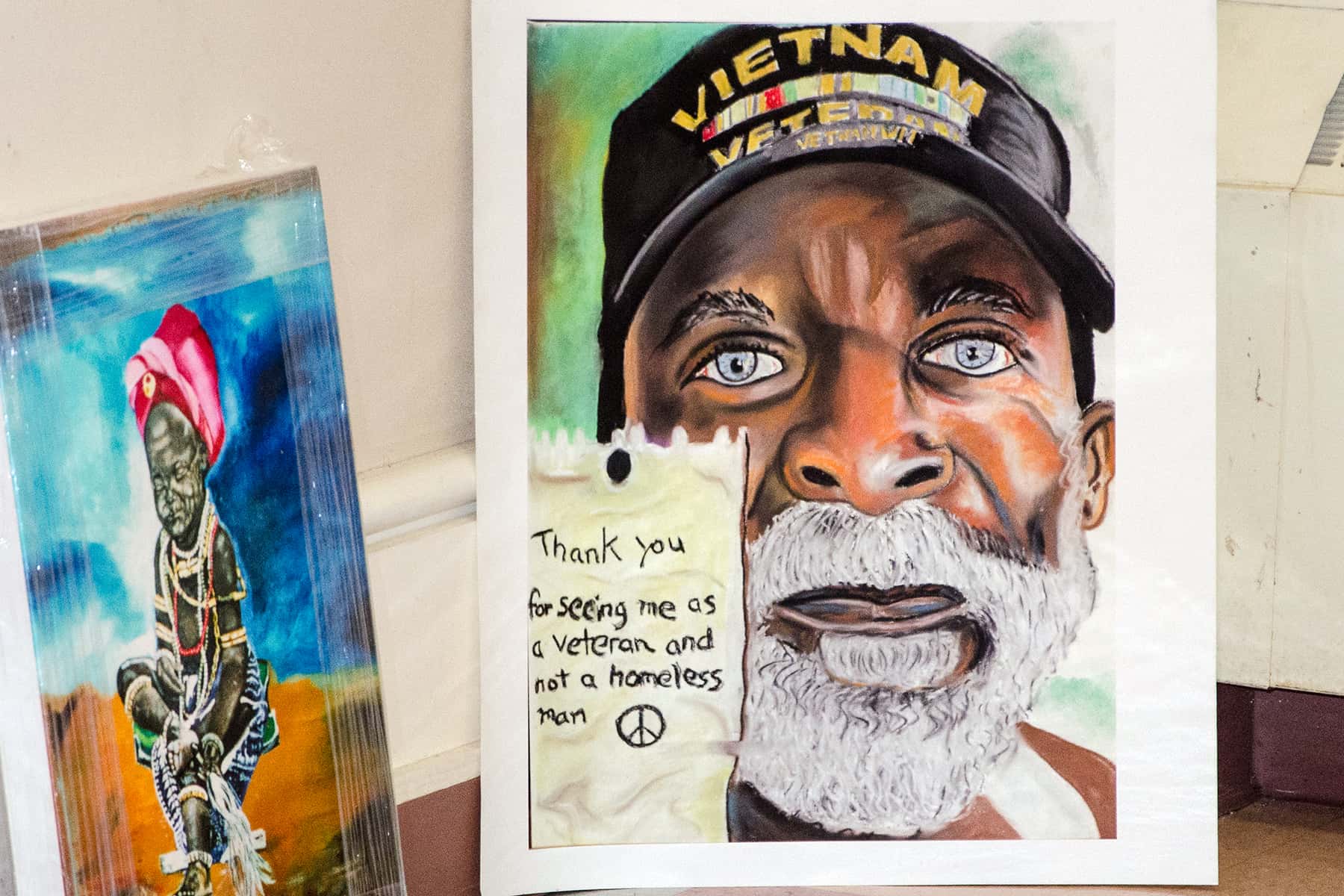

Army Veteran Willie Weaver-Bey, who spent 40 years in prison before being released to Milwaukee, was a former Milwaukee VA winner who went to the national event with his portrait of a homeless Vietnam veteran. The portrait was based on a photo of a man wearing the Vietnam hat he saw on the Internet.

“The guy’s eyes just grabbed me. I decided I had to paint that. I gravitate to those types of people because it’s more powerful,” said Weaver-Bey.

Steel bars, concrete walls and no hope was all Willie Weaver-Bey saw for most of his life after getting out of the Army in 1972, until he escaped. Within two years of his Army hitch, he was in prison for possession with intent to distribute drugs. He got a reprieve in 1989, broke the law again, and was thrown back behind bars a few months later.

“My incarceration, it was for bad decisions, but it was the culmination of a lot of things,” Weaver-Bey said. “It was post-traumatic stress that for years I was not even aware I had. I never even discussed it, because back then you didn’t talk about stuff like that.”

But Weaver-Bey did not find freedom by breaking out of the high-security prisoin. Instead, he found his hope and his freedom in some broken-down paint brushes and an old piece of canvas.

Out of prison since 2015 and with a home, job, and therapy thanks to VA, Weaver-Bey estimated that he had created 10,000 paintings in the last 20 years. One of his favorites works – a picture of an older African-American man with a Vietnam hat entitled, “Thank You for Seeing Me as a Veteran and not a Homeless Man,” earned him a spot previously at the National Veterans Creative Arts Festival in Jackson, Mississippi.

His life turned around one day when he made the decision to learn how to paint, and the process helped him to begin coping with a sexual assault that had occurred at the hands of a military doctor while he was still enlisted. Weaver-Bey said the doctor assaulted him under the guise of performing a prostate exam, and when he fought back he was court-martialed. After experiencing troubles with the law in civilian life, when he got locked away he also locked up those feelings.

“I was the victim. I had wanted to stay in the military, but it killed some of my dreams,” added Weaver-Bey. “A lot of guys in prison, they spend time doing time. They don’t use their time wisely. I didn’t want to get caught up with the prison gangs or the drugs, so I started out doing ceramics and working with clay. It was my way to escape.”

Then Weaver-Bey discovered painting, but he had no idea how to begin. He encountered a man who had been trained in Paris but the inmate never had time to mentor, and begrudgingly gave Weaver-Bey some used up paints and raggedy brushes to get rid of him. But Weaver-Bey persisted, watching the artist for hours to study his technique and reading all he could about painting.

So he painted. Jesus Christ. Muhammed Ali. Ghandi. And he painted some more. A young Elvis Presley. Joe Louis. And Michael Jackson as a child, teen, and adult. And he kept painting. There are portraits of presidents and everyday people. There are portraits of children, horses, and Malcom X. There is even one of himself. And one shows a slave hanging from the tree with the inscription: “This is your ancestor. Say ‘No’ to the N word.”

“This talent, it’s not mine. It belongs to the Creator. He just sat me down long enough to give me this gift. Sometimes I get painting and it doesn’t even feel like it’s me moving my arms. It’s someone else,” Weaver-Bey explained. “I never had a lot of supplies in prison. I got the canvas for one from an old burlap potato sack in the kitchen.”

When parole finally came, it only included $100 and a one-way bus ticket to Milwaukee, since it was the location where he was arrested. The VA and other community resources helped get Weaver-Bey somewhere to live at Vet’s Place Central, which offers transitional housing. The Milwaukee VA also helped Weaver-Bey secure a job and get counseling for undiagnosed PTSD. He now works as a full-time artist and has two more pieces at the 2019 creative arts festival.

© Photo

Milwaukee VA Medical Center