“Friends, I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible. I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot; but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose. But fortunately I had my manuscript, so you see I was going to make a long speech, and there is a bullet – there is where the bullet went through – and it probably saved me from it going into my heart. The bullet is in me now, so that I cannot make a very long speech, but I will try my best.” – Theodore Roosevelt

One hundred and twelve years ago, the Milwaukee courts held one of America’s most notable attempted murder trials. And the “trial,” such as it was, is all the more intriguing because it might not even have been held without the intervention of the gunshot victim himself: Theodore Roosevelt. As noted in a contemporary article, Presidential candidate TR, bleeding in the streets of Milwaukee, rose to his feet and called for the police to have his mobbed, foiled assassin brought to him.

Ever the politician, TR did not want an imminent lynching by the angry crowd to mar his campaign, nor did he want to appear fazed by the attack. Instead, he spoke directly to the perpetrator, directed the police to protect the shooter, and directed his entourage to drive him to the Milwaukee Auditorium to deliver his stump speech.

This article recounts the trial of the would-be assassin, remarkable not only because of its celebrated victim but also because of the uncommon proceedings undertaken in the prosecution. [1]

THE VICTIM

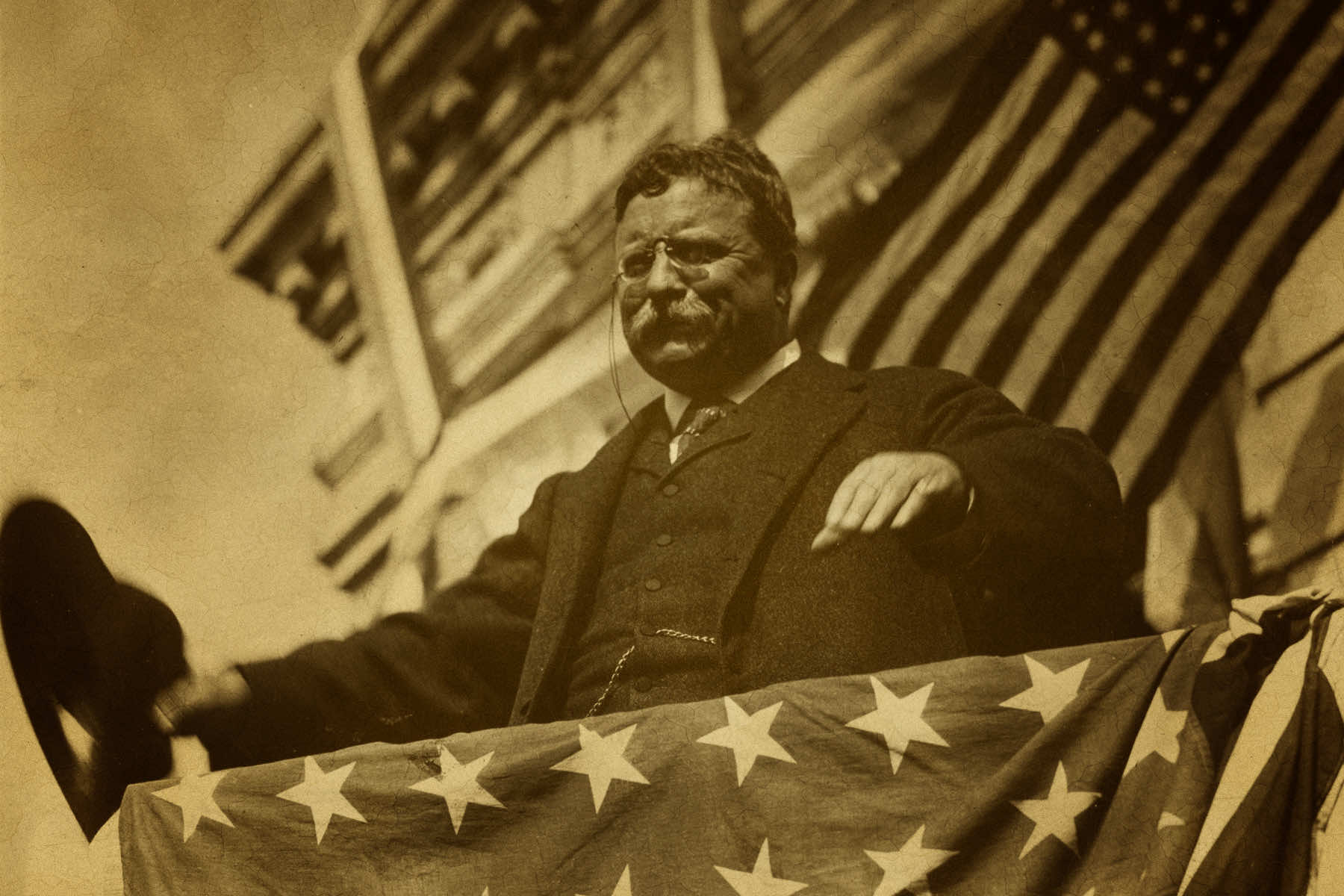

On October 14, 1912, Milwaukee welcomed Bull Moose Party [2] candidate “Colonel” Theodore Roosevelt just weeks before he hoped to be elected to an unprecedented third presidential term. [3] At about 8:00 p.m., an armed man muscled his way through a crowd outside the Gilpatrick Hotel, where TR had dined. [4] The candidate, about to be transported to the Milwaukee Auditorium [5] to speak to 9,000 waiting devotees, climbed into his waiting car and stood on its floorboard at the same time the shooter, at point blank range, aimed a pistol at him. Another person in the crowd struck the shooter’s arm, causing it to drop to TR’s chest level at the same time TR lifted his arm to wave. The gun’s bullet, headed straight for TR’s heart, was slowed by his heavy overcoat, a 50-page speech folded onto itself in his breast pocket, and his metal eyeglass case.

The bullet imbedded in his right rib cage instead of penetrating his lung and heart. [6] Bleeding into his white shirt and a borrowed handkerchief he used inside his topcoat to cover the bullet hole, he delivered his 80-minute speech, telling the crowd that it would take more than a bullet to bring down a Bull Moose. After the speech, TR headed to Johnston’s Emergency Hospital [7] for x-rays and medical assessment. He was transported by train the next day to Chicago’s Mercy Hospital, where he recuperated for over a week (campaigning from his hospital bed) before he returned to Oyster Bay, New York. [8] Back home, he delivered two more campaign speeches, [9] cast his vote, and waited for the results of his third-party presidential candidacy. [10]

THE PERPETRATOR

John Schrank, a childhood immigrant and ex-barkeep at a relative’s New York saloon, was a stocky, studious, quiet, and unassuming man without criminal record or clear indication of mental disorder. He was a self-styled poet and a self-taught student of politics and the history of nations and empires. He wrote lengthy political manifestos, with the centerpiece that the “unwritten laws” of the American Founders — which he entitled “The Four Pillars of our Republic” — were in danger. [11] Apropos of one pillar — that no President should have a third term — Schrank set about to avert that real possibility presented by TR’s campaign.

The day after President McKinley’s September 15, 1901 death, Schrank dreamed that the assassinated President was identifying TR as his murderer and directing Schrank to “avenge my death.” On September 14, 1912, McKinley’s ghost interrupted Schrank’s poetry writing and implored Schrank: “Do not let a murderer sit in the president’s chair.” In a letter found on his person upon arrest, addressed to the People of the United States, Schrank informed the world about these incidents and included in his rant that he was being called both by God and by his patriotic duty to die if necessary to prevent or remove anyone who would be a third-term President.

Schrank bought a gun and stalked TR’s campaign for the next month through seven states and eleven cities, looking for the opportune moment to shoot the candidate. The inspectors’ reports included not just his age (36), address (156 Canal Street, New York), occupation (saloon keeper), moles, marks, weight, height, hair color, and fingerprints (five sets), but also noted that he was a native of Bavaria and noted detailed measurements of his head, cheeks, and ears. [12]

THE UNIQUE LAW IN 1912

During the decades before 1912, both legal and medical professionals, in their respective disciplines and sometimes together, were studying approaches to insanity, mental illness, and feeble-mindedness. In its 1910- 11 session, the Wisconsin Legislature passed a statute allowing the court, essentially, to circumvent a jury trial by appointing a panel of “alienists” (mental health doctors), who could evaluate a defendant as “insane,” either at the time of commission of the alleged crime or at the time of trial. The theory behind the legislation: the battles of the “expert witness opinions” were creating a variety of difficult issues in jury trials. Judges therefore were given statutory authority to opt not to empanel a jury. Schrank’s case was among the first cases in which a judge opted to employ this law.

NOT REALLY A TRIAL BUT, RATHER, A HOMEGROWN LEGAL PROCEEDING

After Schrank’s immediate arrest, District Attorney Winfred C. Zabel [13] interrogated him twice and had him appear the next morning before Judge Neelen in District Court in an effort to evade crowds. Reportedly, 200 people were in court anyway. The D.A. was explicit: John Schrank “is legally sane…. He has a perfect knowledge of right and wrong and realizes that the act he committed was against the law.” The court detective displayed TR’s bloodstained undershirt and shirt before the court asked for a plea to the charge of “Assault with intent to murder or rob. Section 4376.” [14] Schrank pleaded “guilty” outright, waived “examination” (preliminary hearing), and stated that he did not seek an immediate trial.

District Court Judge Neelen imposed $5,000 bail, and then raised it to $7,500 when reminded about concerns of a poisoned bullet in McKinley’s assassination (concerns that were eventually unsubstantiated). The court ordered the bullets from the defendant’s revolver sent to Marquette Professor Summer for chemical examination, ostensibly to assure that the bullets were not poisoned; Schrank assured the court that they were not. Jurisdiction for deciding criminal matters, including sentences, belonged to the Municipal Court. Judge Neelen sent the defendant to appear before Municipal Court Judge August G. Backus during his December Municipal Court session. [15] On the morning of November 13, Judge Backus appointed James Flanders as counsel, who as it turned out served a limited role. [16]

From that point forward, the Milwaukee legal process turned a bit odd, at least to modern sensibilities, with respect to Schrank’s #1. speedy trial rights, #2. bail, and #3. jury trial rights.

Speedy trial rights. Reportedly, it was D.A. Zabel who wanted to delay trial, citing three reasons: to learn the results of TR’s injury should the charge need to be amended, to avoid hurrying the defendant, and because it would be “unwise” to try the case prior to the election and have the “plain criminal aspects of the case in anyway involved in the National political situation.” The D.A. believed that Schrank acted alone, that he could (and would) withdraw his plea prior to trial, and that he was sane.

Bail. Judge Backus increased bail from $7,500 to $15,000 to better assure Schrank’s incarceration, but not because Schrank posed a flight threat. [17] Rather, “movie men” wanted to get Schrank out of jail and into a crowd to “reenact” the attempted assassination scene, record it in pictures before the authorities could prevent them from doing so, then recall the bail and have Schrank remanded to jail. The trash-talking began: Judge Backus would send the bail “sky high”; the movie men said that the amount could not get too high for them to get Schrank out of jail for the pictures.

On October 18, Judge Neelen convened in “open court” with no one present — except the defendant and the D.A. — and ordered the bail to be increased. He also made it clear that if the movie men raised $15,000, he would nonetheless not release the prisoner and thereby permit shameful publicity and undermining of the authority of his court.

Jury trial rights. Schrank ultimately was not allowed to decide to have a trial by jury. Two things were clear: his guilty plea to the charge that “with malice aforethought, [he] did attempt to kill and murder Theodore Roosevelt,” and his wish to accept his fate. But the guilty plea was not without some qualification. Schrank saw his crime as a political crime, not a crime against humanity or the state. Newspapers reflected his demeanor as without passion and with resolution. The following exchange in court changed the course of his prosecution:

Judge Backus: You understand that within [the Complaint] you are charged with having attempted to kill Theodore Roosevelt. Do you plead guilty or not guilty?

Schrank: I did not mean to kill a citizen[,] [J]udge; I shot Theodore Roosevelt because he was a menace to the country. He should not have a third term. It is bad that a man should have a third term. I do not want him to have one. I shot him as a warning that men should not try to have two terms as president. I shot Theodore Roosevelt to kill him; I think all men trying to keep themselves in office should be killed; they become dangerous. I did not do it because he was a candidate of the Progressive Party[,] either, gentlemen.

The D.A., in a complete turnabout, then asserted that “the man is insane. It would be wrong to sentence him for a crime if he was mentally unsound just because he was willing to plead guilty.” He moved the court to appoint a commission of alienists or have Schrank tried before a jury.

Judge Backus ordered a five-person panel of alienists, [18] had them sworn, and allowed them

examine Schrank as often as needed for as much time as they needed. To assuage concerns, the judge made clear that the commission should determine whether Schrank “is sane at the present time.”

Schrank’s attorney does not appear to have been present at the alienists’ sessions or at the legal proceedings. Schrank responded to questions and provided documents to the commission. On November 22, Judge Backus reconvened the legal proceeding and it went forward as follows: the D.A.’s witnesses testified to Schrank’s movements in Milwaukee; and the alienists’ 50-page report was read into the record for the next two hours. The report included five exhibits, including Schrank’s lengthy written statement to the never-convened jury. The commission concluded that Schrank was insane.

The court did not provide for cross-examination, defense witnesses, a jury to evaluate the report or exhibits, or the defendant’s testimony. Judge Backus adopted the report; ordered commitment; and made clear that under the sanity commission’s findings, Schrank would not be able to escape sentence under his guilty plea or a jury determination if at a future date, sanity having been restored, he should demand a jury trial and be determined guilty. As a person declared insane, he would remain a ward of the court.

The disappointed Schrank self-righteously asked, “Why didn’t they give me my medicine right away instead of making me wait? I did it and I am willing to stand the consequences of my act.” As he was led away, he insisted on shaking hands with each of the five alienists.

POSTSCRIPT

Both Judge Backus and what was deemed the “Wisconsin Idea” — the judicial alternative of empanelling alienists in commissions instead of swearing them as disagreeing expert witnesses in jury trials — were widely praised in newspaper editorials throughout the country. [19]

Schrank’s institutionalization on November 25, 1912 in the Northern State Hospital for the Mentally Disturbed in Oshkosh was followed by his transfer to the Central State Mental Hospital in Waupun. Nicknamed “Uncle John” by the staff, he was a model patient for the next 30 years. Had his guilty plea been accepted, he would have served 15 years instead of being institutionalized for 31 years. The alienists determined that he acted on a delusion once; no evidence of similar attempts or other antisocial conduct was ever reported. Curiously, Schrank had no visitors or communications during his entire institutionalization. He died in 1943, three years after Franklin Delano Roosevelt, TR’s cousin, was elected to his third presidential term, and just after FDR announced his intent to run for a fourth term.

Hannah C. Dugan

Lee Matz, Library of Congress, and Everett Collection (via Shutterstock)

Originally published on the 100th anniversary of the assassination attempt as The Strange Milwaukee “Trial” of Theodore Roosevelt’s Would-Be Assassin by the Milwaukee Bar Association in October 2012.

Beginning on August 1, 2024, the Milwaukee County Circuit Court will pilot a specialized Mental Health Court, focused on defendant competency.

1 – Remey, Oliver E., Cochems, Henry F., and Bloodgood, Wheeler P., eds., The Attempted Assassination of Ex- President Theodore Roosevelt (O.E. Remey, Milwaukee 1912), reissued (Roger H. Hunt, Madison 1978); Aderman, Ralph M., ed., Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years (Milwaukee County Historical Society, Milwaukee 1987); Olivar, Willard, and Marion, Nancy, Killing the President: Assassinations, Attempts and Rumored Attempts on U.S. Commanders in Chief (ABC-CLIO, LLC, Santa Barbara, California 2010); Bruce, William, and Currey, Josiah Seymour, eds., History of Milwaukee, City and County, Volume 1 (S.J. Clark Publishing Co., Milwaukee 1922); Usher, Ellis Baker, Wisconsin, Its Story and Biography, 1848-1913, Volume 4 (The Lewis Publishing Co., Chicago 1912); Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology, Volume XI, No. 1 (American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology, American Prison Association, American Society of Military Law, Chicago 1920); Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology & Police Science, Volume IX (Northwestern University Press 1919); “Would-be Assassin Is John Schrank, Once Saloonkeeper Here; A Maniac on Third Term,” Special to The New York Times, pg. 1 (10/14/1912); “Schrank Owns Guilt, Callous, Then Sorry,” Special to The New York Times, pg. 1 (10/15/1912); “Moving Picture Men Try to Get Schrank,” The New York Times (10/17/1912); “Schrank Says He Shot to Kill,” El Paso Herald (11/12/1912); “Sanity Board to Examine Schrank,” The New York Times (11/13/1912); “Schrank to Asylum, Declares He is Sane,” The New York Times (11/23/1912); “Attempted Assassination of Theodore Roosevelt,” Racine Journal (8/13/22); “The Attempted Assassination of Teddy Roosevelt,” Wisconsin Magazine of History, Vol. 53, No. 4 (Summer 1970); www.classicwisconsin. com/features/assassin.html (viewed August 8, 2012); www.linkstothepast.com/milwaukee/mkemarFbios. php (viewed August 7, 2012); www.wisconsinhistory. org/museum/artifacts/archives/001692.asp (viewed August 7, 2012); www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/ fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=13239354 (viewed August 7, 2012); www.classicwisconsin.com/features/assassin. html (viewed August 8, 2012); www.freeinfosociety. com/article.php?id=425 (viewed August 8, 2012); murderpedia.org/male.S/s/schrank-john-book-4.htm (viewed August 8, 2012).

2 – TR was the Progressive Party candidate, but for his campaign he renamed his party affiliation to reflect that he was as “fit as a bull moose.”

3 – TR was nominated as the Progressive Party candidate, much to Wisconsin’s Fightin’ Bob LaFollette’s consternation. Fightin’ Bob wrote a series of highly critical articles regarding TR’s “betrayal” of Progressive Movement ideals. TR’s visit to Wisconsin was meant to shore up the loyalty of progressive constituents in person. In the Wisconsin election results he came in third; Wilson carried the state.

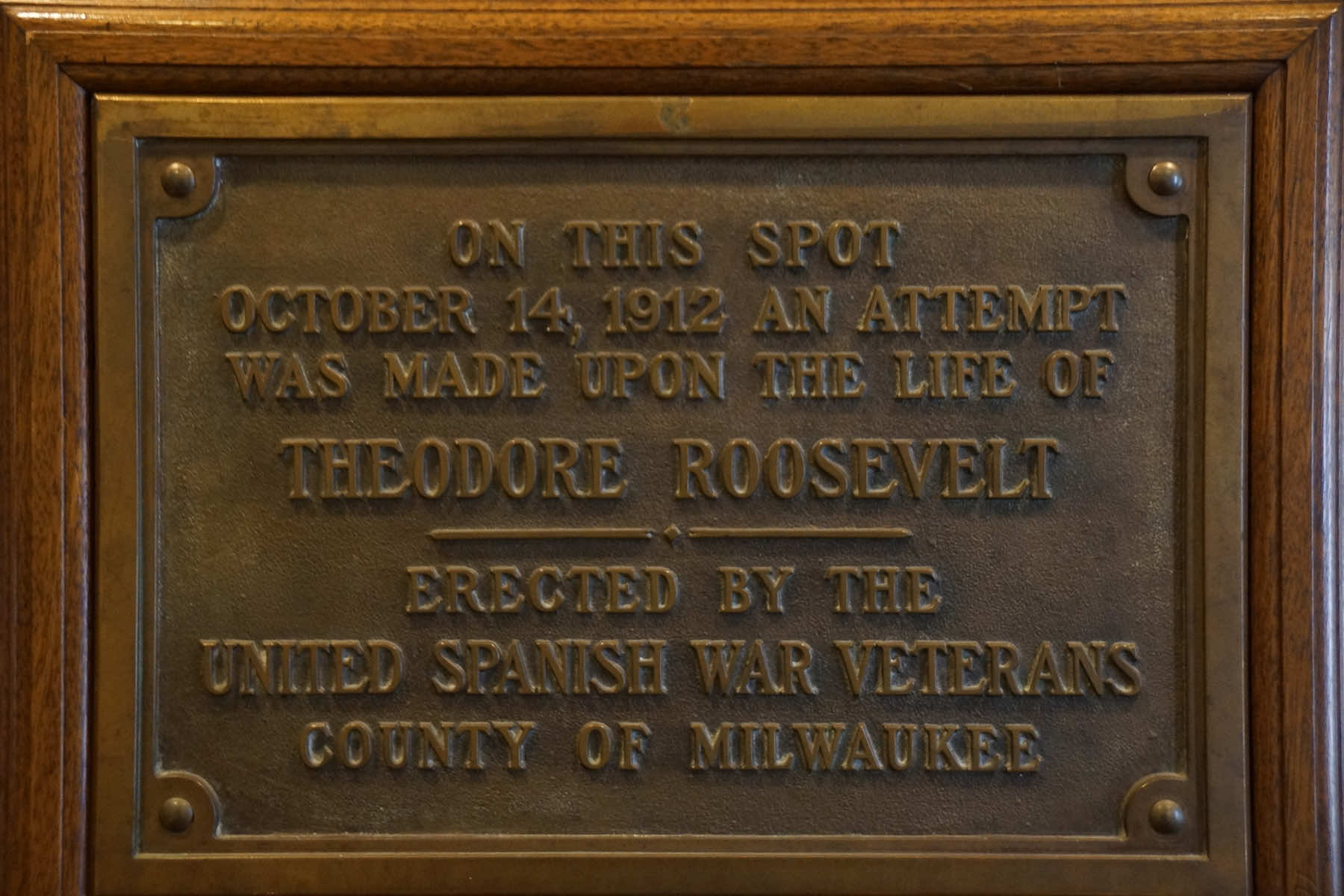

4 – The Hotel Gilpatrick, 223-225 3rd Street (1894-1929), 831 North 3rd Street (1930 – 1941), was closed and demolished in 1941. The Hyatt replaces the hotel at the corner of West Kilbourn Avenue and North 3rd Street, and displays a bronze plaque in its entranceway marking the approximate location of the aborted assassination of TR.

5 – The auditorium where TR gave his speech underwent a $42 million redesign in 2003, and was renamed the Milwaukee Theater.

6 – The bullet was never removed; TR died with it in his rib cage.

7 – Johnston Emergency Hospital, at the intersection of Oneida (now Wells) and Jackson Streets, was operated by the City of Milwaukee.

8 – TR did not have to return to Milwaukee for trial. As Schrank’s appointed counsel argued, because Schrank’s present mental state was in play, “summoning” TR to testify was not likely.

9 – Candidates Woodrow Wilson and President William Howard Taft both intended to suspend their campaigns for a short time following the assassination attempt. But TR sent missives decrying the idea. He claimed that the people needed to be able to hear the candidates and make their choice; he also wanted the electorate to maintain its confidence in him. He resumed his campaign while he recuperated, using telegrams, letters, and surrogates. Before the November 5 election, TR delivered two final speeches — with the one in Madison Square Garden drawing an audience of over 15,000 persons.

10 – TR’s was the most successful third-party candidacy in American history. While Democrat Woodrow Wilson won, incumbent Republican William Howard Taft had fewer popular votes than TR. It is conceivable that, but for the break in TR’s electoral momentum due to the assassination attempt, he would have been elected outright or the election would have been decided by the House of Representatives. A factor influencing Taft’s campaign was that his Vice-President, James Sherman, died on October 30, 1912, leaving Taft without a running mate.

11 – The “Four Pillars of our Republic” were (1) no third

terms, (2) the Monroe Doctrine, (3) only a Protestant by creed can be President, and (4) no wars of conquest.

12 – Although phrenology as a means of determining sanity and criminality was largely out of vogue in the U.S. by the 20th century, recording such measurements became integral in Schrank’s case.

13 – Zabel, born in Germany in 1877, came to Milwaukee in 1884. His father was a Milwaukee County deputy clerk of court. Schooled in Milwaukee, Zabel worked at the Milwaukee Sentinel prior to going to Ohio Northern University, where he earned an L.L.B. degree in 1900. He returned to Milwaukee and became a member of the bar in 1901. He joined W.B. Rubin in law practice and ran for D.A. in 1910, winning as the first socialist D.A. elected in the nation.

14 – “Any person being armed with a dangerous weapon who shall assault another with intent to rob or murder shall be punished by imprisonment in the state prison not more than fifteen years nor less than one year.” The D.A. and Schrank squelched statements that Schrank waited to strike in a state without the death penalty.

15 – In 1859, the Legislature established the Municipal Court of Milwaukee County as a formal criminal court, replacing the criminal jurisdiction of the city’s “police justice system.” The Municipal Court jurisdiction included appellate review of justice of the peace (and later District Court) decisions, and excluded cases in which defendants adjudged guilty would face life imprisonment or death sentences. (These excluded cases remained in the Circuit Court’s jurisdiction.) In 1899, the District Court of Milwaukee County was authorized by the Legislature, and in 1902, it replaced the civil police justice system. The District Court, subordinate to the Municipal Court, heard ordinance, misdemeanor, and traffic cases. The bifurcated District and Municipal Court jurisdictions were absorbed by the County Court system in 1962 and by the Circuit Court in 1977.

16 – James Greeley Flanders came to Wisconsin at age four from New Hampshire. He was schooled in Milwaukee, at Phillips-Exeter Academy, and at Yale College (1867). He spent a year reading law at Milwaukee’s Emmons & Van Dyke before attending Columbia College Law Department (1869). He returned to Milwaukee to practice; eventually became a member of Winkler, Flanders, Bottum & Fawsett; and was elected to the school board and later to the State Legislature in 1877.

17 – The newspapers recorded some of Schrank’s activities in jail: drawing a checkerboard on a blank paper and playing with fellow inmates; insisting on wearing his rosary around his neck (despite authorities’ concerns of suicide); writing, in closely written lines, page after page of foolscap.

18 – The commission consisted of Dr. F.C. Studley (superintendent of a sanitarium), Dr. William Becker (former head of the Northern Hospital for the Insane at Winnebago), D.W. Harrington (a nerve specialist), Dr. W. Wege (an alienist), and chair Dr. Richard Dewey.

19 – Judge Backus subsequently became an active member of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology, and of ABA committees regarding “insanity.”