Medical Mission to Jordan: After more than a decade of Civil War in Syria, and continuing conflicts like the unprovoked Russian invasion of Ukraine that further displaced millions of civilians, understanding the longterm conditions that war refugees face remains relevant. But as public attention fades, such topics do not capture headlines today, even as the impact continues to be felt here in Milwaukee. mkeind.com/jordanmedicalmission

On January 26, the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) concluded its six day Medical Mission to serve Syrian refugees in Jordan. As a photojournalist for Milwaukee Independent, I was embedded with a team of doctors from Milwaukee and Chicago to document their work. On February 6, less than two weeks later and while I was still preparing my news reports and photo essays about the medical mission, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake devastated an already war-weary Syria.

Back in 2018 I wrote a series of news articles about a Milwaukee physician who traveled to Lebanon to provide medical care for Syrian refugees. Dr. Waleed Najeeb had joined a mission organized by SAMS. The interviews and images I used for those reports were all based on SAMS materials, which were provided long after the mission was long over.

After returning in May 2022 from reporting on the war in Ukraine, and Milwaukee’s sister city of Irpin, I took on another assignment in June. I was embedded with Milwaukee-based Forward Latino during their delegation’s fact finding mission to get first-hand information on the situation at and around the Mexico-U.S. Border.

By the fall of 2022, I had developed lateral epicondylitis – commonly known as tennis elbow. Apparently, it was a condition that did not require my athletic ability to get from playing tennis. As a photojournalist covering the Black Lives Matter marches for months – including Kenosha, COVID-19 developments, election riots, and then being an overseas war correspondent had all taken their physical toll on my body.

The lingering repercussions of the pandemic still affected my ability and comfort to be immersed in public situations to produce my style of photojournalism. And the injury also coincided with the process of Milwaukee Independent becoming a member of the Associated Press.

All those conditions were pointing to my need to slow down, and that felt like a punishment. So I had time to consider how I could manage my time and skills. I found that I could actually do more work, while going at a pace that did not require me to show up to report on “Everything Everywhere All at Once” in Milwaukee.

I have looked back on where the idea for the SAMS mission trip came from, and was honestly unable to pinpoint the moment it landed in my thoughts. Perhaps it was random inspiration, a divine suggestion, or just the alignment of an inevitable path that had already been set in motion.

But in November I reached out to Dr. Najeeb and asked, if he planned to participate in another Medial Mission to the Middle East – if I could join him as a photojournalist to do a series about the experience.

The Syrian refugee crisis was the result of a violent crackdown on public demonstrations by the government in March 2011. A group of teenagers had been arrested for anti-government graffiti in the southern town of Daraa. The incident sparked peaceful public protests throughout Syria, which were brutally suppressed by security forces. The conflict quickly escalated and the country descended into a bloody Civil War that forced millions of Syrian families out of their homes. Eleven years later, more than 13.4 million people still need humanitarian assistance.

The Syrian Civil War may have been a world away, but a Milwaukee physician traveling to care for suffering and displaced individuals made it a Milwaukee story.

Part of my motivation was professional and came from my photojournalism experiences in Ukraine and Mexico. I felt guilty that I had decided to report on the war in Ukraine, but not in Syria. Of course, I had not been in a position to cover those events when that war unfolded in 2011.

The other part of my motivation was personal, because the Syrian conflict began the same year I was living in Japan. I had just survived the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami that destroyed my city, which left me homeless and forced my return to the United States after a decade. I was very much a refugee, carrying everything that I owned in a duffle bag, who happened to have an American passport.

I had the experience of being displaced from my life, from navigating a war, and sifting through the human misery that lingered for years after such conditions. I had no expectations about what I could accomplish on a medical mission to help Syrian refugees. But I felt it was the least I could do to bring attention to a mostly forgotten tragedy that continued unseen every day.

When I proposed the idea of going to Dr. Najeeb, I thought maybe something would develop by the summer and it would be months before I heard anything. I was planning, and I am still planning, a return trip to cover the war in Ukraine, as a follow-up to my time in Irpin last year. And that seemed like my next overseas assignment, before one to the Middle East.

But then a few days later, Dr. Najeeb called me to say the deadline for a January 2023 SAMS Mission trip was that day, and did I want to go? I said yes. I would leave in a few weeks, and it would be my first trip to the Middle East. That was another destination I had long dreamed to visit, but abandoned hope of ever seeing.

SAMS approved of my proposal for a journalism mission, and we made plans for what I could achieve on the trip. I would be based in Amman, Jordan for two weeks and travel each day to various cities with populations of Syrian refugees.

I had many hopes for what I could document with my photojournalism, and there was no shortage of pressure during any stage of the process. The least of which was, could I travel with Dr. Najeeb for two weeks and not manage to alienate him to the point that it fractured our friendship.

They say never meet your heroes, because anyone held up in such high esteem would be a disappointment when unable to meet lofty expectations. And there I was, about to travel with a man who I deeply revered.

Over the years I have spent reporting about and photographing Milwaukee’s Muslim community, Dr. Najeeb has always been a source of inspiration for me. His faith is without question one of the strongest I have ever experienced. His personal example, and willingness to explain many things to me, gave me such a deep and abiding respect for him.

Because of Dr. Najeeb, I was able to see the beauty of Islam through his eyes. Even more, I could see his love of humanity without prejudice. In a sense, being a physician was merely a byproduct of his strong spiritual philosophy to make the world better and help everyone he could.

I faced many obstacles and frustrations during the SAMS Mission, but Dr. Najeeb was always a calm and steady anchor who offered me guidance – usually without saying a word. I watched him every day give medical examinations to the refugees who showed up at the SAMS clinics. I saw his selfless joy at being able to ease the suffering of a child, or treat an adult who could not afford basic medicine for their condition. I also saw him reduced to tears when he was unable to do more.

As I write this, I am almost brought to tears myself at the very memory of those amazing moments. Here was a man who had experienced so much in his life, and sacrificed a great deal to join the SAMS Mission, and he was emotional from the limits he faced in being able to help others. A power adaptor was missing for a nebulizer, or we had run out of a type of medication. After so much time and effort to be there in Jordan – and the arduous journey required by the refugees as well, and then to have something so insignificant become an obstacle. It was heartbreaking to watch, but always a triumph when a resourceful solution was found.

I was also very moved by Dr. Najeeb’s gratitude for my work, and constant support of me being a part of the mission. He took the time to explain the conditions of many patients, so I could be a better informed witness to the world.

What I saw over and over again was one of the biggest threats to the health of refugees. Not untreated war wounds, but poverty. Poverty in the form of cheap sugar that rotten the teeth of children. Poverty in the form of mold on household walls – from squalid living conditions outside of the refugee camps. It gave countless patients asthma or some sort of respiratory ailment.

Poverty was the disease, and all the other ailments were just the manifestation of that condition. There are cures for poverty that could be applied around the world – especially here in Milwaukee. But the courage is lacking to implement the necessary treatments.

As a photojournalist, I was constantly observing my surroundings. I watched gravitational forces pull some objects and push others. It became obvious that Dr. Najeeb was not the exception to the rule, in my experience with SAMS volunteers. He was the standard. I found that the best advocates for the refugees were the very same volunteers who had come to Jordan to offer their medical skills.

It was a privilege and honor to be with so many amazing individuals, all working to do good. To do what I was taught as a child – and abruptly discovered as an adult that few people actually had an interest in – making the world a better place. It was so refreshing compared to the personal and professional environments I have been exposed to over the past few years. No one was actively trying to make other people suffer, or live in fear just to score political points. They simply let their light shine, and it was an encouragement for others to do the same.

I am immensely grateful to all the SAMS volunteers I spoke with and spent time around, for showing me there was still a cluster of good people who were all eager to do good work. It was in their DNA, and I found it to be infectious. It also gave me the courage to keep doing my job in Jordan, and to never turn away. There was so much suffering in people that I could not unsee, and yet it was my responsibility to photograph them.

The stories I was told about the conditions of patients quickly became threads that weaved an expansive tapestry of sorrow. As much as I wanted to document every voice, as much as I wanted to be a faithful witness to their situation, people were reluctant to share their trauma. In most cases, photojournalism was the only resource available to me to document what I saw.

Of those many situations, one example remains foremost in my thoughts. She was the first patient one morning towards the end of the mission. A young girl was unable to sleep well, because she could not close her eyelids. When she was barely a year old, her home had been hit by a rocket blast that left her face horribly burned. Eight surgeries in as many years had tried to reconstruct her face.

As I assembled the photo essays for this series, I had to review thousands of the images that I took. When I came to her picture, a part of me was unable to remember that I had taken them. They were hard to look at as photos, yet I had stood there in front of her and taken those pictures. I took many photos of her. It was one of the hardest things I have done in my career, but I signed up to do the hard things.

Every bit of my soul wanted to look away and leave the poor child alone. It felt like aiming my camera was somehow trampling upon her human dignity. In my mind, I saw the hated stereotype of a TV journalist who capitalized on the misery of someone for clicks and ratings.

But the world of 2023 needed to see the continued cost of a war that started in 2011, the human cost of suffering that never goes away just because we do not see it in the headlines. I did my best to capture her human dignity in the short time I spent with her. It pains me to think about her, of the future she was denied. It will pain others to look at my published photos of her, but for other selfish reasons. Seeing her condition is uncomfortable. Being able to turn away and avoid that discomfort is the privilege we have here in America. We should ask ourselves more about why we are so uncomfortable.

The little girl was someone’s daughter. She arrived with her mother, but I never learned about her father. If people in Milwaukee are reluctant to care about children in Milwaukee, how can I help them to care about a little Syrian girl thousands of miles away? It was the same question I asked about Ukraine. I know the answer. I cannot make a difference. But, I am still determined to try.

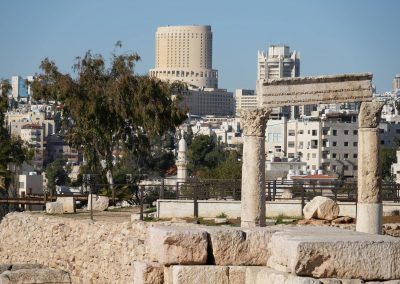

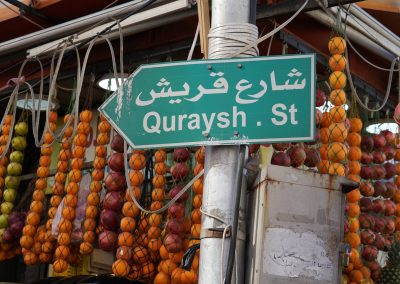

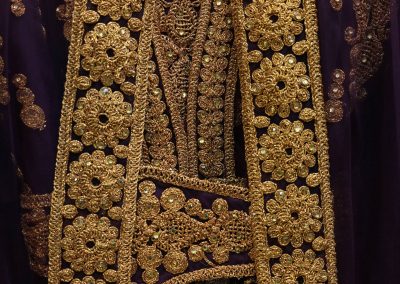

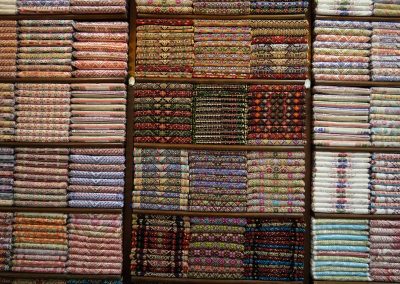

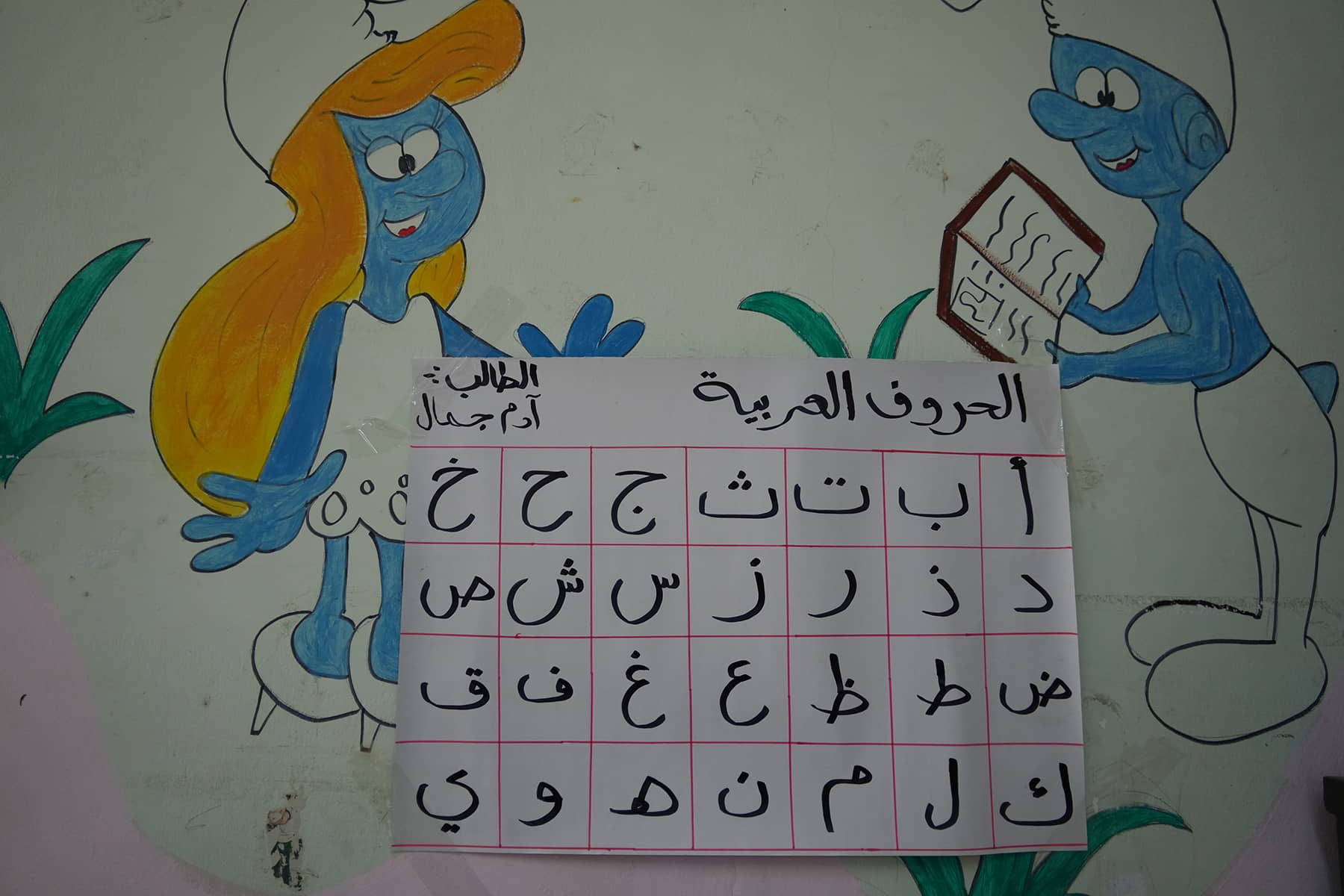

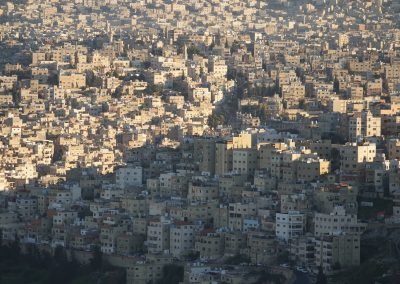

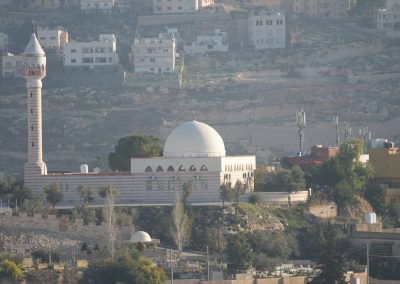

The photos selected for this collection have nothing to do with the SAMS Medical Mission. They are from the couple days before the mission started, as Dr. Najeeb and I walked for miles around downtown Amman. They reflect the historic and cultural sites we visited. I wanted to include them as a foundation for reference. For my series from Ukraine, I had a photo essay that just showed people living their everyday lives in places like Kyiv and Lviv while the war went on. That was partly the purpose of this idea. The majority of Syrian refugees in Jordan do not live in a camp. They live in small communities in cities and towns scattered all over.

Arriving in Jordan was my first experience to travel to the Middle East. I was able to explore and discover many wonders, just before I was immersed in the refugee environments. As an introduction for this series, and for the readers who follow each part, the order and arrangements were intentional.

Originally, this series Medical Mission to Jordan: A journey from Milwaukee to help Syrian Refugees, was scheduled to publish the week of February 27. It would follow after the one year anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24. But because the earthquake happened in Syria, just after I left that area, I felt it important to alter the schedule to publish the series as soon as possible.

As I type these last words, I can hear the pings of my messaging alerts from SAMS chat groups. Devastating reports from volunteers on the ground in Syria are reaching me by the hour. These are the very same people who I was just with a couple weeks ago in nearby Jordan. And yet again, they have stepped up to help without being asked, because they saw the need and saw the tragedy and still wanted to make the world a better place.

This editorial feature is one of a multi-part explanatory series about the “Dr. Majdi Omar” SAMS Jordan January 2023 Medical Mission. The journalism project embedded a Milwaukee Independent photojournalist, from January 21 to 26, 2023, with a group of Syrian American doctors from Milwaukee and Chicago. It documented their trip to Jordan and the medical work done at clinic locations like Za’atari Camp, Salt, Jerash, En Albasha and Marej in Amman, and Basma in Ma’adab. Medical Mission to Jordan: A journey from Milwaukee to help Syrian Refugees, shares the personal voices, stories, images, and conditions around those involved in the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) mission to Jordan. It also explores the refugee experience, and the intimate connections of local medical professionals, who put their work on hold and left their families behind for a couple weeks to provide healing to others who have endured a generation of trauma.

Series: Medical Mission to Jordan

- Medical Mission to Jordan: Traveling from Milwaukee to document the conditions of displaced Syrians

- Refugees in need: How the Syrian American Medical Society is able to provide vital medical services

- Waleed Najeeb: A spiritual duty to bring specialized relief to those suffering from a decade of war

- Za’atari Refugee Camp: Syrians struggle with a decade of life in the bubble of a temporary shelter

- Jihad Shoshara: How medical advocacy empowers Syrians living with guilt and trauma from a distance

- Deadliest in a decade: Untold numbers remain buried under rubble in Syria after devastating earthquake

- Medical Mission to Jordan: A visual diary from a week with Syrian refugees and SAMS volunteers

- Hazar Jaber: Advocating for oral health so poverty does not make sugar into a poison for children

- Bassel Atassi: Holding onto a family identity after Syria went from a home country to a ghost country

- Medical Mission to Jordan: The faces of Syrian refugees and their health struggles after years of war

- Abrar Qureshi: Finding a "Street of Happiness" among the faded ruins of hope in Za’atari

- Abdullah Chahin: Building a collective purpose to provide medical care as a Syrian in exile

- Zein Barakat: A spirit of volunteerism that nurtures an abundance of compassion, love, and humility

- Hima Humeda: A Syrian college student’s story from childhood heart surgeries to caring for war refugees

- A clarity of vision: Giving displaced Syrian children the ability to see a world full of possibilities

The 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck parts of Syria and Türkiye on February 7. It came a week after the SAMS Medical Mission ended, and while Milwaukee Independent finished the final production of this editorial series. The public is encouraged to make donations to the Syrian American Medical Society in support of their vital crisis relief work.

Lее Mаtz

Lее Mаtz