Every year on March 1, Koreans pause to remember the wave of patriotic fervor that swept their country more than a century ago.

Known as the March First Movement or the Samil Movement, the historic uprising on March 1, 1919, is widely recognized as a catalyst in Korea’s quest for independence from Japanese colonial rule. Over time, the 3-1 Festival Day (삼일절 Samiljeol) has become a powerful symbol of national pride and self-determination.

Though the March First Movement began on the Korean Peninsula, its meaning echoes with the Korean diaspora around the globe. From solemn ceremonies in Seoul to special services in communities abroad, Koreans and those of Korean descent gather to honor the legacy of the early independence activists.

In Milwaukee, where a small but vibrant Korean community has thrived for decades, commemorative events have likewise taken shape. They have shed light on how memories of that monumental day more than a century ago were carried across oceans and remain preserved to this day.

HISTORIC CONTEXT OF THE MARCH FIRST MOVEMENT

The roots of the March First Movement trace back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Korea, then known as the Korean Empire, found itself caught in a complex geopolitical tug-of-war involving Japan, China, and Russia.

Japan formally annexed Korea in 1910, imposing strict colonial governance that curtailed basic freedoms that fundamentally altered the structure of Korean society. By the time 1919 arrived, numerous Korean intellectuals, students, and religious leaders had grown increasingly frustrated with Japan’s oppressive rule.

Inspired by international calls for self-determination following World War I, independence-minded groups formed in major Korean cities and in diaspora communities outside the peninsula. The ideas voiced by President Woodrow Wilson, who famously spoke about the principle of self-determination in his Fourteen Points speech to the U.S. Congress in 1918, also contributed to heightened awareness among Koreans that they had a right to control their own national destiny.

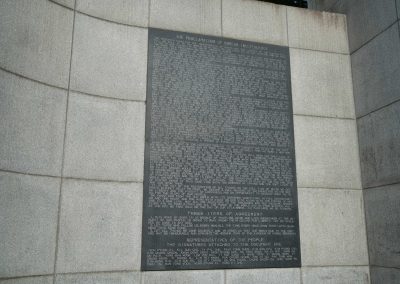

On March 1, 1919, activists gathered in Seoul’s Pagoda Park, renamed to Tapgol Park in 1991, to read the “Proclamation of Independence.” It was a historic document that affirmed Korea’s inherent sovereignty and rejected Japan’s colonial authority.

The crowd carried copies of the proclamation and recited it aloud, sparking peaceful demonstrations that quickly spread throughout the country. People from all walks of life, such as farmers, merchants, students, and clergy, joined the cause. They were unified in their desire for an independent Korea.

MOMENTS OF HOPE AND BRUTAL CRACKDOWN

What began as a largely peaceful demonstration soon encountered a harsh Japanese crackdown. Colonial authorities responded with sweeping arrests and violent reprisals. Historians estimate that thousands of Koreans were killed or wounded during the ensuing weeks, and many more were taken into custody. The movement’s impact, however, was too profound to be entirely suppressed.

The forceful response from the Japanese administration drew international attention to Korea’s plight, garnering sympathy in the United States, Europe, and other parts of Asia. Newspapers around the globe reported on the Korean protests, highlighting the urgent call for national liberation.

While the March First Movement did not immediately achieve independence, it profoundly influenced subsequent generations of activists and planted the seeds of a broader push against Japan’s imperial rule.

KEY FIGURES AND BROAD PARTICIPATION

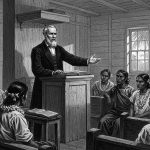

The March First Movement was influenced by leaders such as Son Byong-hi, one of the most prominent signatories of the Korean Declaration of Independence. But it was in many ways a bottom-up phenomenon. Teachers, students, monks, and everyday citizens formed a spontaneous drive for liberation. That inclusivity galvanized people across class and religious lines.

Among the 33 signatories of the original declaration were representatives of various religious communities, including Christianity, Buddhism, and Cheondogyo – a Korean religious tradition that blended elements of Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, and Korean shamanism with a distinctive focus on the belief in the divinity of all people.

Even after many of the leaders were arrested and imprisoned, ordinary people kept the protests alive in cities, towns, and rural villages. Japanese authorities soon recognized that stamping out the movement would not be as simple as arresting a small circle of leaders.

Although the arrests initially curtailed large gatherings, the underlying sentiment endured. The efforts of a united population left a deep imprint on Korea’s national consciousness, one that would resonate in the decades to come.

IMPACT ON KOREA’S EMERGING IDENTITY

Japan remained in control of Korea until the end of World War II, but the sacrifices of March 1, 1919, did not fade. The movement became a symbolic touchstone in Korean society, shaping a renewed sense of cultural identity and unity against external domination.

Exiled activists founded the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea in Shanghai just weeks after the March First Movement began. That government in exile served as a rallying point for Koreans, both at home and abroad, who believed in the possibility of an autonomous nation-state.

Through diplomatic missions, political organization, and education programs, the provisional government worked toward one goal: ending Japan’s colonial grip on the Korean Peninsula. Many historians note that the movement served as a turning point in modern Korean history.

Nationalism gained traction and cultural campaigns, from the spread of hangul literacy to renewed interest in traditional art forms, were further fueled by the heightened sense of unity. Scholars often describe 1919 as the moment when aspirations for independence fully crystallized across diverse segments of Korean society.

COMMEMORATIONS IN MODERN-DAY KOREA

March 1 today is a national holiday in South Korea, known as Samiljeol. Each year, a formal ceremony is held in Seoul, typically at the Seodaemun Prison History Hall where Japanese authorities once detained and tortured many independence activists.

Officials and citizens gather to lay flowers and pay respects to the memory of those who were punished for protesting colonial rule. Flags of South Korea are also on display throughout the country.

Schools organize lessons that focus on the significance of the March First Movement, ensuring that new generations understand the sacrifices made by their ancestors. On television and in newspapers, coverage often centers on living descendants of the independence activists, along with stories of unsung heroes who have not always received widespread recognition.

Over time, commemorations have evolved to include cultural performances, poetry readings, and re-enactments of the 1919 demonstrations. In recent years, technology has played a bigger role. Virtual tours of historic sites, online exhibits, and social media campaigns have broadened the scope of memorial events, making them more accessible to Koreans worldwide.

CONTEMPORARY RELEVANCE

Beyond the commemoration of a singular event, the March First Movement has shaped broader social and political currents in modern Korea. Advocates for democracy, human rights, and social justice frequently invoke the spirit of 1919 to mobilize civic participation.

The legacy is also visible in art, literature, and popular media. From films set during the colonial period to best-selling novels that depict everyday life under Japanese rule, the era remains a subject of exploration for Korean creatives.

Some see parallels between that chapter of history and contemporary struggles around the world, emphasizing the universal themes of autonomy and dignity.

In North Korea, the March First Movement is commemorated through state-organized events that emphasize anti-imperialist narratives in line with the government’s broader ideology.

Despite the stark political and social differences between the two Koreas, the holiday remains one of the few traditions shared by both North and South, underscoring their common heritage rooted in a history predating the peninsula’s division.

While ceremonies in the South focus on honoring independence activists and celebrating a national sense of identity, the North uses the occasion to highlight themes of anti-Japanese resistance and national sovereignty.

The mutual recognition of March 1 testifies to an enduring cultural link that transcends the heavily guarded border, offering a rare glimpse of shared historical identity amid ongoing tensions between the divided people.

KOREAN DIASPORA COMMUNITIES IN THE UNITED STATES

The United States is home to one of the largest Korean diaspora populations in the world, with significant communities in Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago, among other cities. Korean Americans have upheld the legacy of March 1 by hosting events that mirror those in South Korea.

Many Korean churches in the United States hold special prayer services on or near March 1, reciting sections of the Korean Declaration of Independence and offering reflections on the sacrifices of past generations. Universities with strong Korean studies programs often sponsor lectures or cultural performances commemorating the movement’s significance.

Over the decades, diaspora celebrations have taken on new forms, integrating elements of both Korean and American cultural traditions. Music concerts featuring both Korean folk songs and American jazz or gospel have been part of some commemorative events.

Korean American youth groups often use the day to host community service projects or to highlight issues of social justice, drawing connections between historical struggles for freedom and present-day challenges.

MILWAUKEE’S KOREAN DIASPORA

While the Korean community in Milwaukee is smaller than in other metropolitan cities, it carries a unique story shaped by the city’s industrial history and the arrival of Korean immigrants over several decades. Many settled in Milwaukee in the post-Korean War era, seeking employment in manufacturing or attending local universities for advanced degrees.

In the 1970s, Korean students and professionals arrived to study at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and nearby institutions, finding support networks through churches and cultural associations. Today, these organizations serve as focal points for passing down traditions to younger generations.

Korean churches in Milwaukee have become particularly important for the community’s collective identity. Religious leaders and laypeople organize various programs that bridge cultural gaps, offering Korean language classes for children and Korean cooking lessons that invite the wider Milwaukee community to partake in Korean cuisine.

Korean American groups in Milwaukee have hosted commemorations for significant national holidays over the years, including the 3-1 Festival Day.

CONNECTING PAST AND PRESENT

For Milwaukee’s Korean diaspora, honoring the March First Movement is about more than recalling distant historical facts. It is an opportunity to celebrate their heritage and share it with friends and neighbors in Wisconsin. It is also a time to engage in dialogue about the universal ideals of human rights and the persistence of national pride under adversity.

On March 1 in Milwaukee, it is not uncommon for first-generation immigrants to recount stories handed down by their parents or grandparents who experienced Japanese rule directly. Those intergenerational conversations offer a link between contemporary Korean Americans and the activism of the past.

The anniversary of the Samil Independence Movement also illuminates the determination that continues to shape the diaspora experience in the United States.

The story of March 1, 1919, resonates because it remains a testament to the power of collective action. It reminds Koreans, whether in Seoul, Milwaukee, or elsewhere, that unity and advocacy can set meaningful change in motion.

Although more than 100 years have passed since the March First Movement, its significance shows little sign of waning. In South Korea, the day continues to serve as a national symbol, anchoring the country’s narrative of independence.

In places like Milwaukee, it underscores the enduring bond that many Korean Americans hold with their ancestral homeland. The day is a proclamation of a singular truth: that Korea was, and still is, an enduring nation with a proud sense of identity.

© Photo

Lee Matz, and Evelyn Jung, AminKorea, Dooly, Stock For You, Lim Lim (via Shutterstock)