On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln delivered one of the best known speeches in American history, at the dedication of the Soldiers National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

This essay is part of a series of opinion pieces. Each one is no longer than 272 words, the length of Gettysburg Address, and responds with a view of how Lincoln’s spoken ideas in Gettysburg are relevant to America in 2017.

Great tasks remain before us in 2017, just as Lincoln charged in his 1863 Gettysburg Address. Re-emphasizing founding propositions: equality and liberty. Resisting distractions: resentment, political pettiness, and shiny objects which detract from advancing the common good and human dignity. Re-envisioning government: the roles of and sacrifices of flesh-and-blood citizens of, by, and for representative democracy.

His Address charts a quick timeline. Between the first and second sentence, Lincoln lopes over 87 years from the Declaration of Independence to the Civil War. By the fourth sentence, Lincoln places himself in the Pennsylvanian farm field, before hundreds who were shivering in the November wind. From his vantage, point he saw mourners and survivors; shallow graves and still unburied fallen.

And in the distance he sees “us.”

“It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work.” It is we the people who shall form a more perfect union; we who hold equality and liberty as self-evident truths. In Lincoln’s timeline democracy did not perish; it is “nobly advanced” when citizens take up the unfinished work relevant to their time.

And “takes” in 2017 are ubiquitous. Taking to task politicians at town halls. Taking on crafted disunities. Taking up on appeal. Taking down statues. Taking to the polls. Taking the moral high ground on repeals. Taking up the Twitter gauntlets. Taking it to the streets in pink hats; against torches; for equity. Taking a knee on a football field. Taking out elected-office nomination forms.

Heeding Lincoln’s poetic and prophetic words, advancing self-governed citizenship under the Constitution and under his Emancipation Proclamation, “it is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.”

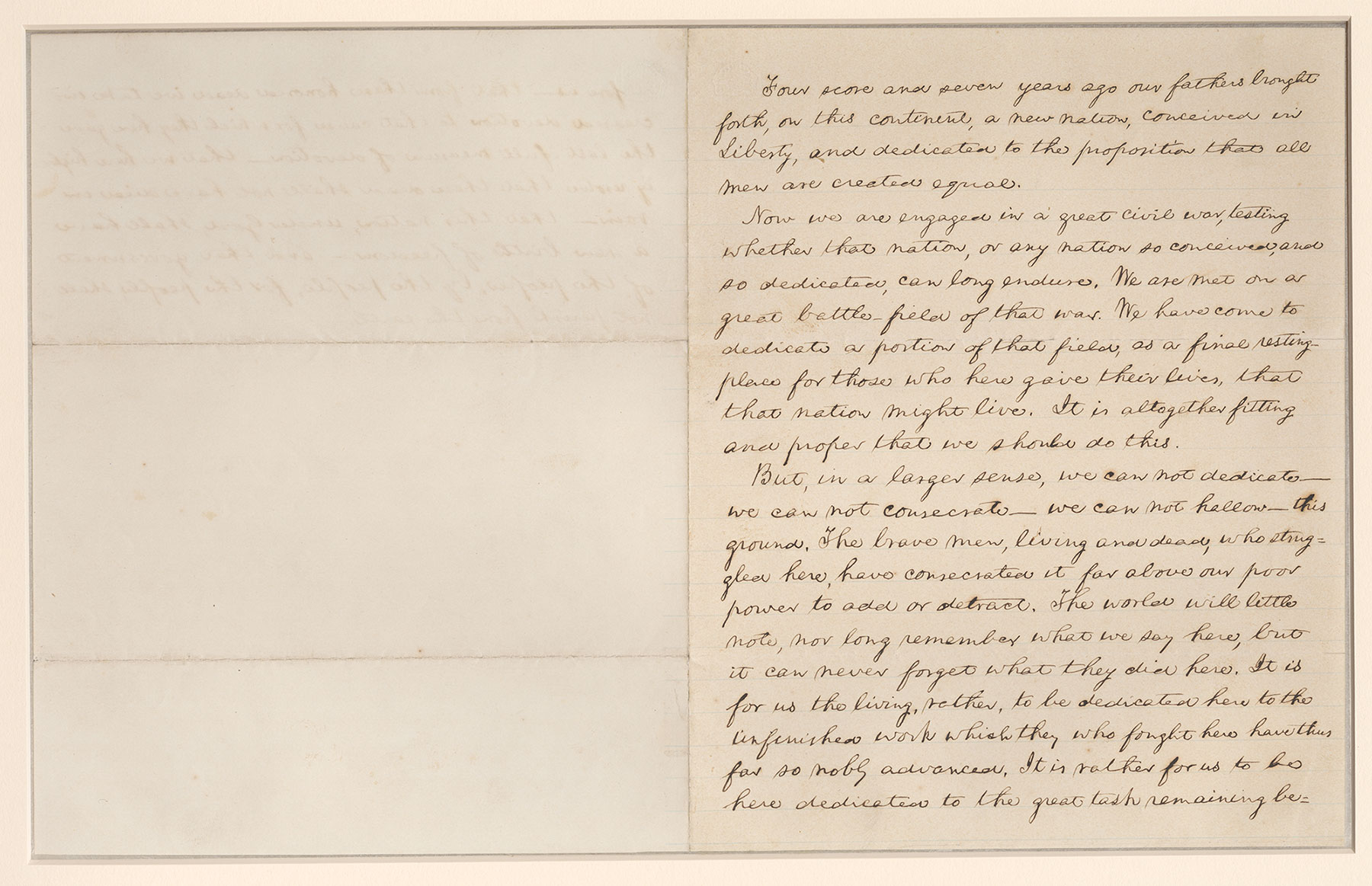

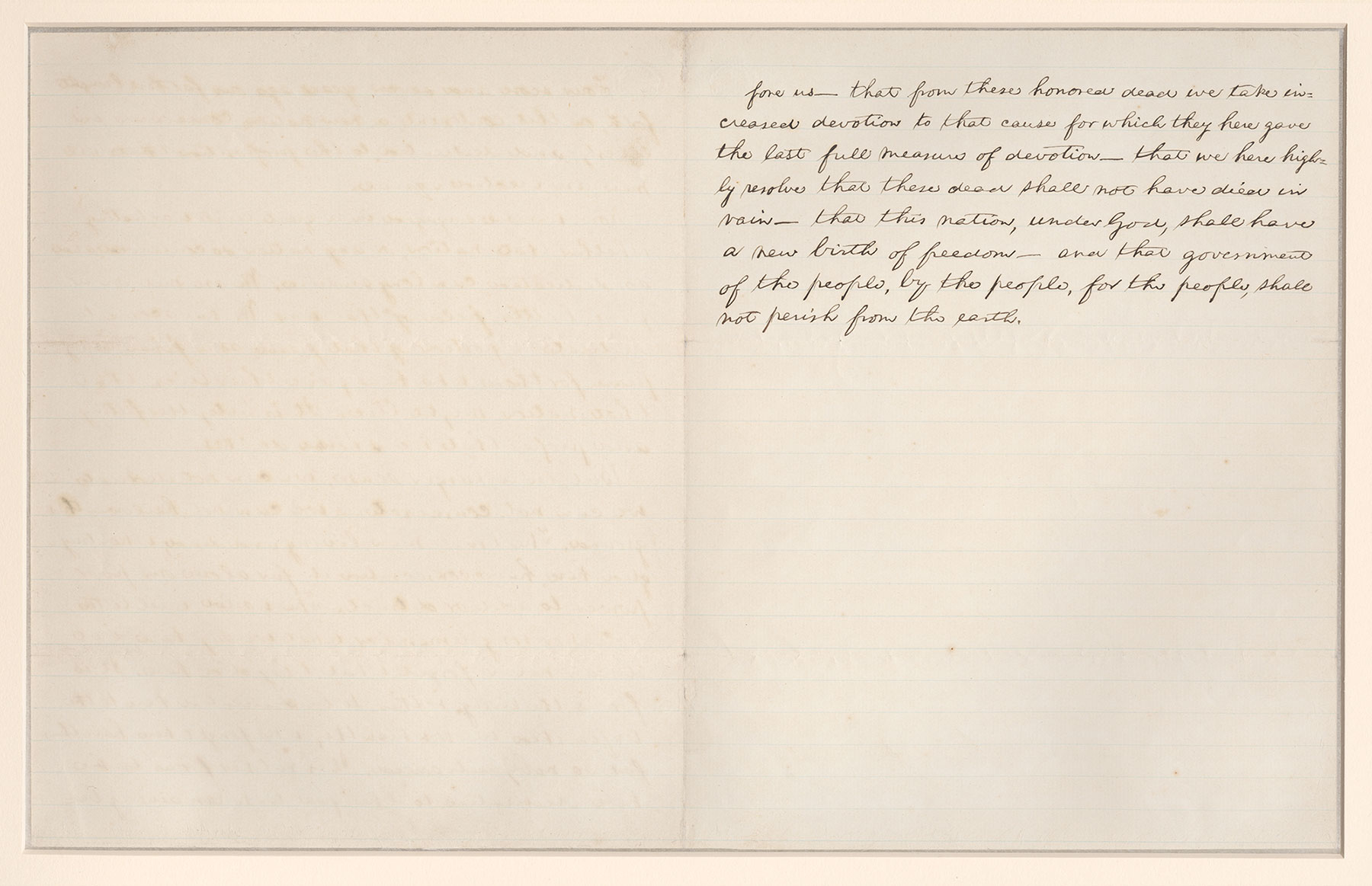

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address (The Bancroft Version)

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives, that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Cornell University Library’s copy of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is one of five known copies in Lincoln’s hand. Written out by President Lincoln at the request of U.S. historian, George Bancroft, this copy, the fourth that Lincoln composed, is known as the Bancroft Copy.

Hannah C. Dugan is an elected trial judge for the Milwaukee County Circuit Court.

Library of Congress