On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln delivered one of the best known speeches in American history, at the dedication of the Soldiers National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

This essay is part of a series of opinion pieces. Each one is no longer than 272 words, the length of Gettysburg Address, and responds with a view of how Lincoln’s spoken ideas in Gettysburg are relevant to America in 2017.

Can a nation conceived in liberty and the idea of equality in the late 1800s survive in the face of current-day strife? That is the question Abraham Lincoln poses in a mere 272 words in the Gettysburg Address.

And it is in the very brevity of the address that Lincoln answers the question: it will be our actions, not words, that determine the survival of a government of, by, and for the people.

We are now engaged in a great civil war of words, testing not only whether a nation so conceived can endure – but at times even questioning whether it should. We are met mainly on the battlefields of Twitter, Facebook and cable news, the final resting place of a million sharp barbs, hot takes and sick burns. It is fitting that they should remain there. Buried.

It is up to us, then. Citizens. To decide whether the unfinished business of a noble experiment will be taken up or left to lie, unconsecrated. A new birth of freedom is possible – it is always possible – if we are willing to renew our faith in ourselves, if we are willing to little note nor long remember what was said on Morning Joe, if we are willing to extend a hand and have the courage to have faith in one another once more, one nation, under God, imperfect, imperishable.

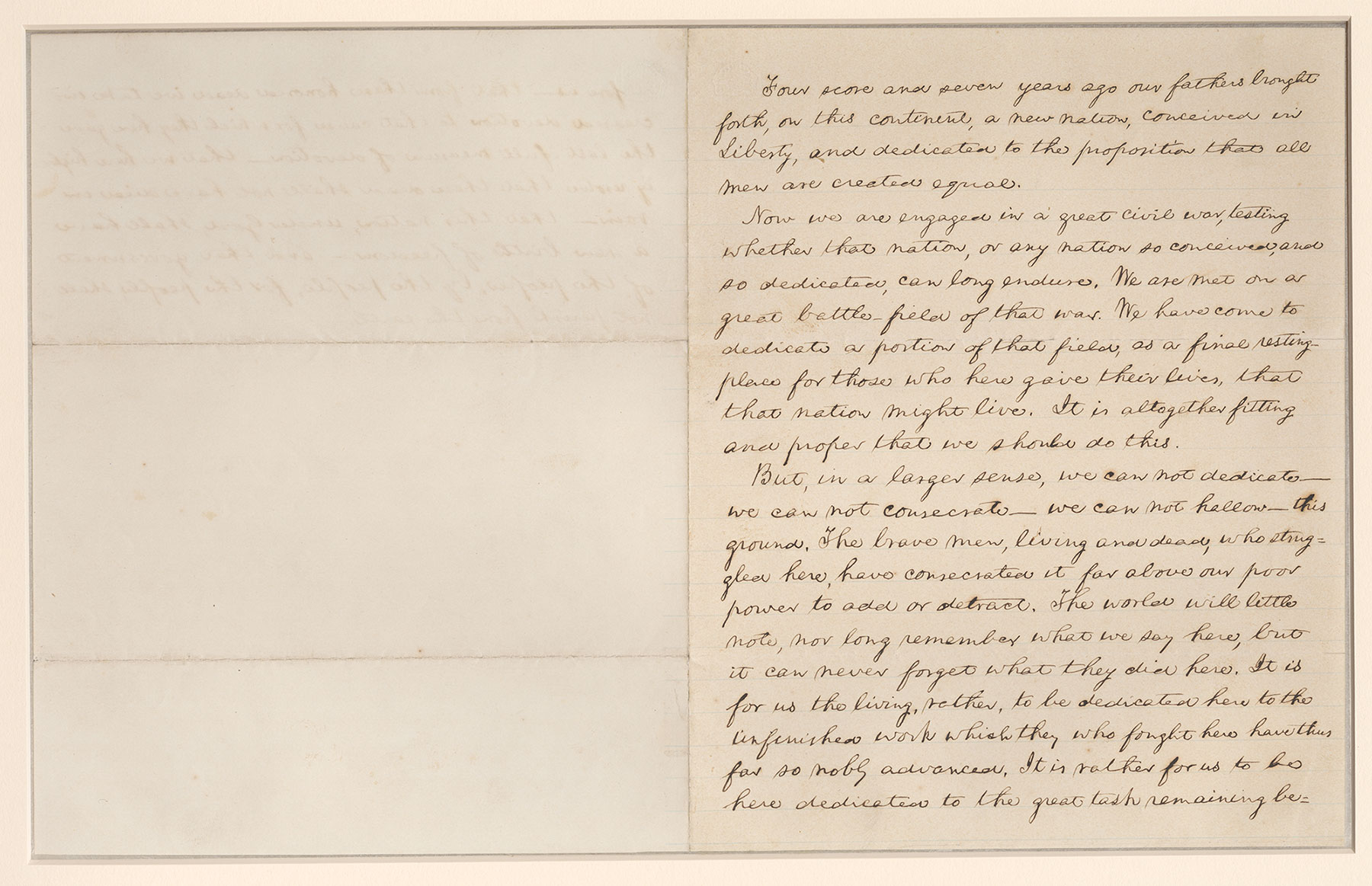

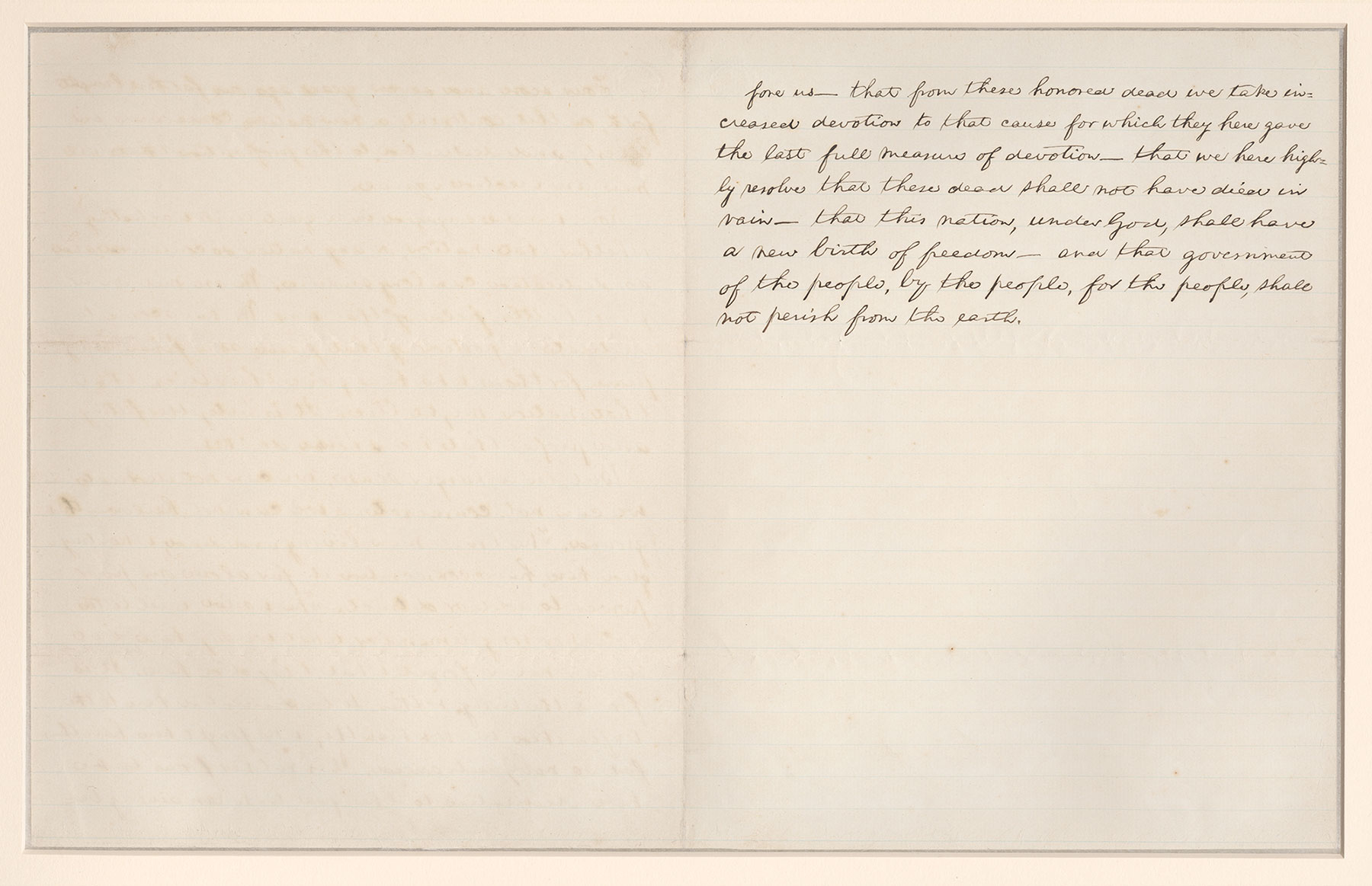

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address (The Bancroft Version)

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives, that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Cornell University Library’s copy of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is one of five known copies in Lincoln’s hand. Written out by President Lincoln at the request of U.S. historian, George Bancroft, this copy, the fourth that Lincoln composed, is known as the Bancroft Copy.

Peggy Dooley is a writer and editor who lives in Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin