Mass shootings have taken a toll on the collective wellbeing of American psyche.

It has been over a month since the Marjory Douglas High School shooting that claimed 17 lives, and we continue to feel disgust stemming from our inability to make any real progress or changes to create safer societies.

Judging by the large scale student activism, numerous walkouts, and planned marches encouraging continual civic engagement, this debate is far from over. Complicating matters is the recent school shooting where the gunman was mortally wounded by the school resource officer in Maryland, saving countless lives.

So what do we make of the political discourse around arming educators with firearms in classrooms and schools across the nation, will it help or hurt?

Personally speaking, immediately following this shooting, I also identified with the raw rage of survivors and the desperation they must feel to effect gun policy by moving forward with legislation to keep schools safe. I also felt this same drive to keep religious sanctuaries safe following our tragedy at the Sikh Temple in Oak Creek, where a white supremacist fatally shot six people including my father.

Some of the organizations that our community worked alongside included Moms Demand Action, Everytown for Gun Safety, Brady Campaign, and WAVE, to name a few. Back then, it also felt like an uphill battle to pass any kind of common sense gun policy and stop the next large scale gun rampage from happening.

Just as we felt like we were making momentum in reaching our goal, “it happened!”

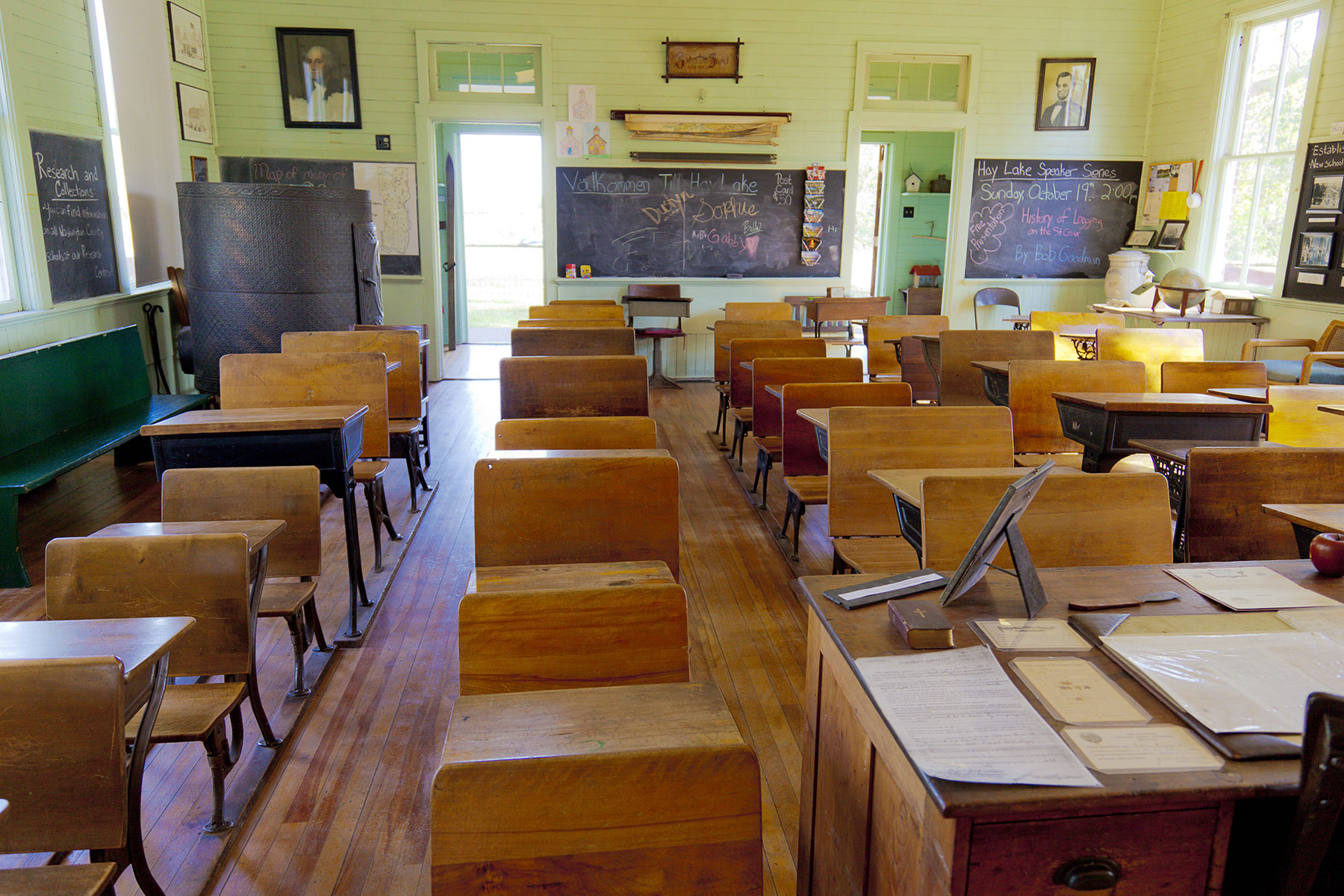

On December 14, 2012, while I was teaching Social Studies to an 11th grade class in Milwaukee, I was notified of mass casualties at an elementary school in Newtown, Connecticut. The news was such a shock that I needed to walk out and spend some time in the hallway before coming back.

I did not want to alarm my students, but news on social media spread fast. That day, the entire school staff shared in the burden of controlling, consoling, counseling, and caretaking. The unimaginable happened that day, 20 six and seven-year old children were gunned down in cold blood inside their classroom by a shooter armed with a military style AR-15.

Following the tragedy at Sandy Hook, much like Parkland, the entire collective consciousness turned to, “what can we do to make sure this never happens again?”

The NRA and outspoken pro-gun supporters immediately presented the idea to train and arm teachers to neutralize active armed shooter threats. What makes the situation unique this time is that a sitting U.S. President is echoing the same sentiments of support by “arming trained teachers to make schools safe.”

As a former law enforcement officer for the City of Milwaukee, I trained for 9 months on how to shoot a 40-caliber Glock handgun and a standard issued shotgun. We trained, and trained, and over-trained on scenarios and tactical positions. We developed muscle memory and got used to the role that extreme stress plays upon the body when challenged.

We practiced perceived threat drills, de-escalation and neutralization tactics until we were ready for the reality of policing. Every human’s natural and automatic response to danger is to flee, however as police we were expected to develop the courage to run towards danger after 9 months of training.

Even with that length of time, and stringent training, some Milwaukee police officers still failed at fighting through their natural response of freeze, fear, and flight. That is exactly what happened at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High when then Deputy Scot Peterson waited outside and listened to gunfire instead of proceeding towards the threat.

So it can be fairly asked, how would we expect teachers to develop the psyche to be in combat situations?

Furthermore, arming educators does not make any empirical sense, because there is no evidence that shows where an armed “civilian” educator has ever stopped an active shooter threat. It is even more rare to have active gunman stopped by resource officers or paramilitary trained staff.

The proposal to arm educators was made purely and speculative on the baseless premise offered by the NRA, “A good guy with a gun, will stop a bad guy with a gun.”

It is a dangerous premise that assumes a good guy could be anyone. From a public health perspective, this would be like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) endorsing the idea that oranges can fight influenza – simply on the recommendation from an orange vendor – that oranges are the only source of Vitamin C.

There is much more likelihood that arming educators will only increase the amount of guns on school property, and increase the likelihood of accidental discharges. We have already seen recent evidence with two recent mishaps in California and Virginia.

As a society, we also need to understand the significant impact that loaded weapons have not only on the physical setting, but will have on the collective psyche of the entire educational environment. Teachers are already bearing the brunt of societal responsibility. The duty to respond to an active threat would add to this already deep psychological burden.

When I policed, what kept me up at night was not what I experienced, but what could have happened. This is the same fear shared by most first responders. Because these educators will have a firearm on their possession, they will constantly struggle with “what if” scenarios. Perceived threat and constant exposure can have very damaging physical symptomology such as hormonal imbalance, digestive disorders, increased cortisol, immune system imbalance, infertility, and memory concerns. Liken this to the psychosocial impact of “active shooter drills” and the effects that these drills have on students, staff, and the school culture.

As a country of laws and spiritual faith, have to figure out where does all this madness stop. If we arm teachers, do we also arm religious institutions, theatre employees, restaurants, malls, coffee shops. At some point, we need to de-escalate the volatility of gun violence in our country. This will require the passing of gun reform legislation while respecting gun ownership. These are not competing issues, and protecting public health will not be built as a result of a small arms race.

My experience as an educator was one of building empathy, connection, and trust. I had many good days and some bad. Some stressful scenarios, like breaking up fights, and even an incident where the principal of our school was held up at gun point in front of me. Even though I was extensively trained with firearms, I appreciate that I never had the option of being armed while teaching in a Milwaukee school.

All of those situations could have played out far worse. So what happens the first time educators are expected to neutralize a threat? What about the guilt that they have to live with if they are unsuccessful, if they have to take a life? What if the armed educator is shot and killed, or if a student is hurt or killed by an armed educator? What happens to the healthy school climate of higher learning?

Arming teachers will not just have a social and logistic effect, but will have a deeply spiritual and psychological impact. Bad social behavior due to poverty has already created a harsh atmosphere at underfunded schools and throughout an educational system tasked with raising children.

While I am relieved that the shooting in Maryland was thwarted by the school resource officer, and casualties were minimized, there is a real and infinitely larger danger of putting guns into the hands of educators, and adding to the volatility of already charged educational settings.