Edward Morgan wrote about his experiences in Kyrgyzstan, sharing them on social media from January to June 2023. Some of those posts, like entries from a travel journal, have been assembled here.

Individually, the raw and unedited entries share an account of his time in the Central Asian country. Collectively, the posts express a larger narrative about the social and regional conditions in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

FEBRUARY 2

Last night I went to a Beatles concert at Bishkek’s Opera and Ballet Theatre. An orchestra of strings and percussion played Beatles hits under a random stream of Beatles videos. They trotted out a few singers too, who gave passing renditions of Let it Be and Yesterday. I might’ve dismissed it, like I have dismissed Pops concerts by American symphonies, as pandering to sell tickets. But I was reminded of The Story Smuggler by Georgi Gospodinov, wherein he recalls growing up in Bulgaria and how Beatles records and other contraband were smuggled through the Iron Curtain and treasured as emblems of the West. And so I listened with different ears, mindful that here in Bishkek too, these songs were forbidden fruits of democracy.

It’s been 31 years since Kyrgyzstan declared its independence but the country is still wrestling with the shadow of Soviet times, like so many countries of the former Soviet bloc. The Ukraine war is a chilling, cautionary reminder. Democracy here dangles in the balance between quasi-authoritarianism, corruption, and the dream of a civil society. That is what I heard last night, besides faux-classical versions of those great pop songs. Or at least that’s what I felt: a lingering ache for a more authentic freedom.

FEBRUARY 10

Manas is the central hero of Kyrgyz cultural lore. The Manas epic, which tells his story (and that of his son and grandson) is an oral poem 20 times longer than Homer’s Odyssey. It is the world’s longest epic poem. According to the epic, Manas held the 40 Kyrgyz tribes together in the 10th century as they battled and parlayed with the Chinese and other Turkic tribes. Today, the name is ubiquitous: Manas Airport, Manas University, Manas Street, and so on.

In Bishkek there are two huge statues of Manas. In front of the State History Museum, Manas is portrayed as the classic nomad warrior. In Philharmonic Square, he rides a magical horse while slaying a dragon. Beside and below him are statues of his wife and his spiritual advisor. On either side of the square there are busts of half a dozen famous manaschi. The manaschi are those who recite the epic tale – or sections of it – in a melodic a capella chant like Homer must have done, or like a Gaelic bard or an African griot. One famous manaschi recited the epic for 111 hours over 5 days.

FEBRUARY 18

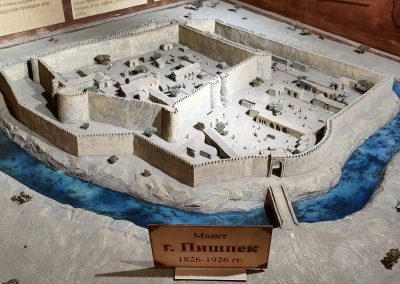

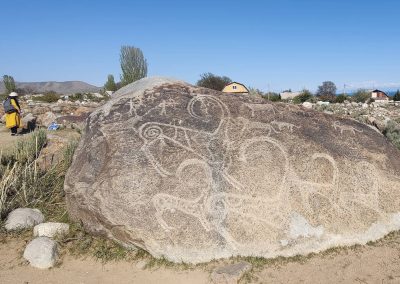

On a first visit to the State History Museum what struck me most were the petroglyphs and shamanistic totems; reminders that Tengrism is at the root of Kyrgyz culture. I was reminded of seeing ogham carved into Irish standing stones and dolmens, and petroglyphs on rock walls in New Mexico. All were made with similar tools, probably at roughly similar eras, and for me they reflect a cosmology in which human beings, nature and the spirit world are deeply intertwined. I acknowledge my tendency to romanticize preindustrial societies and modern life is obviously a vast improvement in many ways. But I do feel that in losing a sense of sacred connection to the earth, we’ve lost something essential.

FEBRUARY 23

It is Defender of the Fatherland Day. It is not hard to relate to a Veteran’s Day, but it feels strange to celebrate soldiers of the Red Army a day before the anniversary of Russia’s latest invasion of Ukraine. Even so, hundreds of thousands of Kyrgyz died serving in the Red Army during the Great Patriotic War (WWII). At Victory Square, there is a huge granite monument like the frame of a yurt. An eternal flame burns below it.

At the history museum, there is also a new exhibit on the siege of Leningrad. The Russian defense was certainly heroic, but I could not help but wonder: is this exhibit a subtle vote of support for Putin’s “de-Nazification” of Ukraine? Moscow has many loyal “friends” in Kyrgyzstan.

I acknowledge the importance of honoring veterans. I also acknowledge the contradictions.

At Ala-Too University, two first-year classes give a charming performance with music, dance and poems to honor Kyrgyz veterans. Afterwards, I am speaking with the kindly professor with whom I share an office and we talk about my various responses to the day. He smiles, nods and tells me in his youth he was in the Soviet Navy. He served on a submarine that helped transport the mid-sized missiles back to Russia after the Cuban Missile Crisis. Contradictions abound.

MARCH 5

Last night in Bishkek I met two young Russian men who fled the conscription in September. I have met various others. I heard an estimate that 700,000 young Russian men left the country in late fall. They are scattered through Eurasia, Central Asia, Serbia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Georgia and Finland. They dropped everything and left home. Some had an easy passage, others a rough journey through crowded, guarded borders. Some were welcomed by local populations and others by Russians who fled when the war began. Some are struggling, some have gone back, but many have found work and are beginning new lives. I admire them.

This morning, one of the young men sent me a link to a site where another young man posted the story of his difficult journey from Moscow into Kazakhstan. It ends like this:

“Lastly, I want to morally evaluate my act. We are not runaways. They might not have remembered me at all during mobilization. We voted. Our votes were not counted in the voting, our voices were not heard in the streets. So they will be heard economically. We will not pay VAT and other excises, because we do not buy food, gasoline and other amenities of life in the Russian Federation. We will not pay personal income tax, because we will no longer work in the Russian Federation. We will not raise the economy that feeds this bullshit with our work. And we will not pick up a machine gun, we will not point it at the innocent, we will not dig a meter of a trench, we will not participate in organizing a communication system for bastards. I am not alone. They say that since September we are already in the region of a million. And since the beginning of the war, millions. This is our vote against.”

MARCH 8

It is International Women’s Day. There was a protest march this morning and other events all week. This evening at the Kyrgyz State Theatre a packed house watched a passionate one-act play about domestic violence. The production was sponsored by an NGO and USAID and it will you are the country in the upcoming months.

Kyrgyz law recognizes gender equality but old habits die hard. Many Kyrgyz girls are married off at a very young age. The practice of bride kidnapping also persists. As for domestic violence, in this country of 6.7 million:

- 95% of all domestic violence victims are women.

- Police register 10,000 cases of domestic violence each year (but how many cases go unreported?)

- More than 100 women have died from domestic violence in the last 6 years.

MARCH 22

I have learned more about Kyrgyzstan’s national game, kok-boru. They say the game was first played with a wolf’s carcass and was invented by tribes who herded sheep. The tribes would kill the wolves who preyed on their livestock. Eventually, they made up an entertaining use for a wolf’s carcass. Then perhaps wolves got scarce as the nomads settled down, so they replaced the wolf with a goat or a sheep. Different variants of the sport are played in southern and northern Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan. Each variant has a different name and some different rules but the gist is the same: the players try to throw a headless animal’s carcass into a circular goal.

In August, Kyrgyzstan will host the first ever kok-boru World Cup, featuring clubs from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Russia and the USA. Over 20 teams are scheduled to compete on the shores of Lake Issyk-Kyl for a prize of 2 million som (approximately $22,700).

APRIL 5

My first-year English classes took a field trip to the history museum, so I went along. It was fun to share the experience with them and what I appreciated most this time were the shyrdaks (traditional Kyrgyz rugs) and traditional clothes. Afterwards, we took a walk through the artists’ open-air gallery nearby and then took a picture under the statue of Kurmanjan Datka.

Kurmanjan (1811-1907) was ahead of her time. As a young woman she defied tradition and fled (some say into China) to avoid an arranged marriage she didn’t want. Later she came back and married for love. Her husband was a Datka (a righteous governor) and his dream was to unite the warring southern tribes. When he was assassinated, she took his place, which was extraordinary in that patriarchal era. She made peace among the tribes and became famous for her diplomacy. Later, as Tsarist Russian forces conquered Central Asia and brutally subdued the northern tribes, Kurmanjan realized the Russians were too powerful and surrendered to save Kyrgyz lives. The Russians treated her with respect and called her a queen. It was 1876. The Kyrgyz would be vassals of Russia for the next 115 years.

(Speaking of tribal subjugation, the Black Hills War and the Battle of the Little Bighorn took place in 1876 and 1877 in Montana Territory.)

APRIL 11

I polled a class of 18-year-old students, asking them how many languages they speak. Their answers ranged from two (Kyrgyz and Russian) plus intermediate English, to speaking or having a passive understanding of four or five. A comparable class in the United States might have a number of bi-lingual students, but typically there would be none with three languages except foreign students or immigrants. This is partly a function of geography, partly a failing of U.S. education and partly the legacy of isolationism and the arrogance of empire.

To learn another language is to see differently, to encounter different values and to realize that our culture and our individual lives could be different. There’s no magic pill for bigotry but immersion in the other is profound. Every teenager should spend a year in a foreign country; the more different from their own, the better.

APRIL 14

My apartment in Bishkek is close to Panfilov Park, where there’s a sprawling 1970’s-era amusement park nestled among the trees. There are no gates or entrance fees, just a bunch of low-cost rides for kids of all ages, shooting galleries, carnival booths, bumper cars and food stands. Now that it’s spring, families, teens and couples stroll through the park day and night, eating ice cream and cotton candy. Approaching the park, you hear pop music and girls screaming gleefully on scary rides.

At the southeast entrance there’s a statue of one of Russia’s most famous war heroes: Ivan Vasilyevich Panfilov. There are books and movies about him. Throughout the former Soviet Union there are streets and city districts named after him, and even a mountain. In the 1930’s, Panfilov was suppressing rebellions in Central Asia. But his posthumous glory stems from the Battle of Moscow in 1941, where he and his 28 Guardsmen paid the ultimate price, holding off a Nazi attack and destroying 18 German tanks before they died. Russia’s defense was indeed heroic, so hearing that story it felt odd and inappropriate that this hero’s park is now a sort of rinky-dink amusement site.

Then I read that an investigation by Soviet authorities back in 1948 determined that the Panfilov Battle of Moscow story was a fabrication. Propaganda. And in 2016, Sergei Mironenko, director of Russia’s State Archive of Socio-Political History, made those findings public. Unsurprisingly, Mironenko promptly “voluntarily” resigned his post, at which point Russia’s Culture Minister was quoted as saying, “Even if this story was invented from start to finish, if there had been no Panfilov, if there had been nothing, this is a sacred legend that shouldn’t be interfered with. People who do that are filthy scum.”

Turns out the amusement park is actually appropriate for Panfilov. His glory is just another merry-go-round of “alternate facts.” Not unlike Russian news today, justifying the invasion of Ukraine and the deliberate slaughter of civilians.

APRIL 21

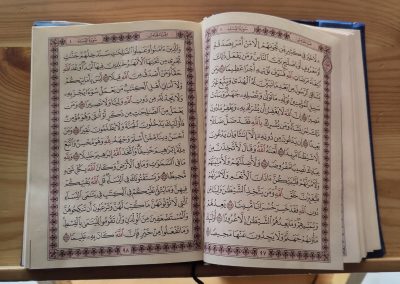

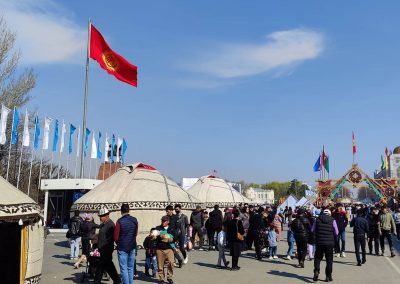

Today in Kyrgyzstan it’s Eid al-Fitr: the end of Ramadan. It is a day of feasts and family gatherings and this afternoon it seemed like everyone in Bishkek was in the streets or parks and in good spirits. For me, it’s been a relief to spend the last few months away from America’s angry socio-political furor in a culture that’s more tolerant and relaxed.

By the way, contrary to U.S. stereotypes, only 20% of the world’s Muslims are Arab and many Arabs are not Muslim. About 33% of the world’s Muslims live in Southern Asia and 15% live in sub-Saharan Africa. With 1.9 billion followers, Islam is the world’s second largest and fastest growing religion.

MAY 3

World Press Freedom Day. There is a small, unassuming statue on Bishkek’s Abdrahmanov Street. It is a memorial to Gennady Pavlyuk, an investigative journalist who became an enemy of former Kyrgyz President Bakiev. Pavlyuk died in 2009, after being thrown from a sixth story window with his hands and feet bound.

Things have certainly improved since then but this country is still a long way from having a truly free press. Last September, prominent journalist and human rights defender Bolot Temirov was deported to Russia, despite being a Kyrgyz citizen. The government also recently passed a “false information” law, which allows them to block any news they label as “false” without a court order. This violates Kyrgyzstan’s constitutional right to free speech.

The 2023 World Press Freedom Index was published today. Summarizing the annual study of 180 countries (and accounting for attacks on journalists, propaganda, fake news and so on), it depicts the current environment as “very serious, difficult or problematic” for journalists in seven out of every ten countries. Kyrgyzstan slid 50 places this year and now sits at 122 in the ranking. The other four Central Asian countries rank lower.

MAY 9

Victory Day marks the surrender of Nazi Germany in 1945. This morning in Bishkek, 15,000 people came out for the annual Immortal Regiment March. Many carried photos of relatives who fought in the war. Parades were held in Osh, Jalalabad, Talas and other towns.

March organizers asked participants not to carry flags or symbols that relate to any current military operations. “Our fathers and grandfathers who fought in the same trench — Kyrgyz, Russians, Ukrainians and many, many others — fought for peace. For a world without the brown plague of fascism and Nazism. And we must not shame their memory. The Immortal Regiment of Kyrgyzstan has been and remains a campaign that unites peoples.”

Meanwhile, Kyrgyz President Japarov was attending Victory Day in Moscow, along with the other Central Asian presidents. Japarov met yesterday with Putin and they discussed plans to “deepen military and technical cooperation,” as well as economic and cultural relations to reach “a new level of integration.”

Perhaps this is all just ceremonial talk but it is well known that Russia and Belarus are circumventing Western sanctions with trade through Central Asia. It is probably only a matter of time before the West begins to broaden the sanctions.

The Kyrgyz government is officially neutral. And definitely, this country needs the support of the West.

Kyrgyzstan is a small country between a rock and hard place.

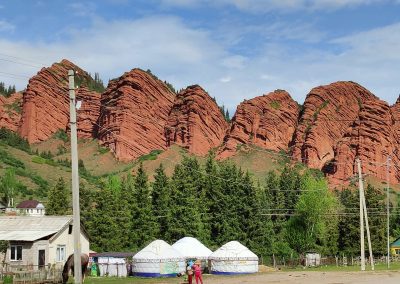

JUNE 14

I am sitting in Almaty’s airport, feeling gratitude, the melancholy of goodbyes and thinking of all the posts I didn’t write. I wanted to write about Kyrgyz cuisine and the traditional wedding I attended. I wanted to write about Central Asia’s youthful population and the impending water crisis. The list goes on and on but it’s time to stop.

A friend recently asked me, “What was the best part of being in Kyrgyzstan?” I said, “The people, of course.” But then I talked about the fascination of Kyrgyz culture and identity and the complex ties to current world events. And then I talked about the beauty of the mountains and Lake Issyk-Kul. I only scratched the surface of it all, but I hope to go back someday. For now, gratitude.