A seasoned theatre director, educator, and playwright, Edward Morgan has spent many years living and working in Milwaukee, a city he fondly regards as his creative home. Known for his engaging storytelling and deep connections to the performing arts, Morgan frequently returns to Milwaukee for various theater projects when he is not teaching in post-Soviet states.

I spent this past August in Azerbaijan, a place I might not have found on a map ten years ago. It sits in the Southern Caucasus, with Russia to the north and Iran to the south, as a predominately Muslim nation with more than 10 million inhabitants.

Azerbaijan is rich with oil and natural gas, and allied with nations and corporations in the East and West. Having spent much of 2023 in Kyrgyzstan, my initial impressions were colored by similarities between the two countries, since both are Turkic, post-Soviet states with secular, authoritarian governments.

These notions soon gave way to a fascination with Azerbaijan’s unique story and geopolitics.

I went to Azerbaijan thanks to a State Department grant called the Citizen Diplomacy Action Fund. CDAF grants are awarded to projects that address U.S. public diplomacy goals such as Human Rights issues, environmental education, community building, strengthening Democratic institutions, and such.

Each grant funds a team of U.S. initiators in collaboration with local partners. I was fortunate to pair up with a young man from Chicago who had studied in Baku and had ties with an eco-tourism company there. Together we designed and ran a summer camp in a northern village. But before and after the camp, I spent some time exploring Baku.

Baku is the capital of Azerbaijan and the largest city in the Caucasus, with a metropolitan population of nearly 3 million. Perched on the Absheron Peninsula on the western shore of the Caspian Sea, the city is both old and new.

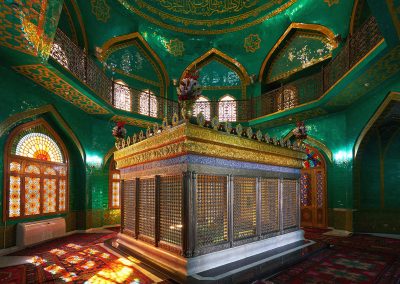

It was settled in the Bronze Age and has been a center of trade ever since. Arriving in the heat of summer, I was immediately struck by the juxtaposition of history and modernity, with medieval sandstone walls and mosques in the shadow of modern skyscrapers and futuristic-looking buildings like the Aliyev Centre, whose curved structure evokes the symbol of infinity.

At night, the iconic Flame Towers light up the sky, three flame-shaped glass buildings that rise above the city that are lit with LED displays. Outside the bustling tourist areas, Baku’s architecture and rhythm sometimes reminded me of Bishkek and Almaty, but by and large it felt more cosmopolitan and optimistic.

Along the bustling streets of Baku, I found myself reflecting on my own experiences in Milwaukee, a much younger city but one with its own rich history intertwined with the currents of industry and culture. Just as Milwaukee has transformed from a manufacturing hub into a vibrant cultural center, Baku is undergoing its own metamorphosis, driven by its oil wealth and strategic geopolitical positioning.

THE REGION & EARLY HISTORY

The Southern Caucasus region has a population of 20 million. It includes Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan and is about the size of Wisconsin plus a third of Iowa. It is named for the Caucasus Mountains, which extend 800 miles from Russia’s Black Sea coast to the Caspian Sea. The region also has deserts, fertile plains, and coastlines, but until modern times the Caucasus was largely defined by its rugged mountains and diverse ethnic groups.

British journalist Thomas de Waal described the Southern Caucasus as the “lands in-between” because they lie between the Black Sea and the Caspian, between Europe and Asia, between Russia and the Middle East, and between Christianity and Islam. For centuries, the region was a passageway between these realms.

East-West trade routes passed through Baku and Tiflis (Tbilisi). Waves of invaders passed through, including Turkic tribes, Persian empires, Alexander the Great, Mongols of the Golden Horde, the Ottoman Empire, the Russian Empire, and the Bolsheviks. I imagine few regions of comparable size have seen as much traffic of people, goods, and armies. It is also a region with a long history of violence – and most recently, between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

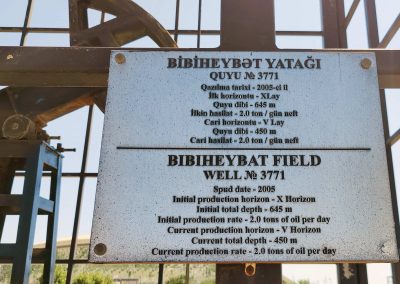

But as the Flame Towers of Baku clearly attest, the defining aspect of Azerbaijan is not mountains but blazing oil. It has long been called the “Land of Fire” for the pockets of burning oil and gas that seep throughout the Absheron peninsula. From ancient times, Baku residents used chunks of oil-soaked earth for heating.

Armies of the first Persian Empire used Azerbaijani oil as an incendiary weapon. Troops of Alexander the Great carried it in wineskins and earthenware crockery and used it for lighting. Centuries later, Marco Polo went to Baku and wrote about seeing geysers igniting and lighting up the night sky.

BEGINNING OF THE MODERN ERA

The country’s modern era began in 1846 when the first Baku oil well was drilled. Before a dozen years had passed the first oil refinery was in construction and enterprising Westerners had begun to invest. The Nobel brothers from Sweden financed a refinery and began shipping barrels of oil across the Caspian Sea to Russia in the world’s first oil tanker. The Rothschilds financed a cross-Caucasian railway from Baku to Batumi on the Black Sea.

In one generation, Baku turned from a “sleepy Persian town” into an international, industrial city with her northern suburbs shrouded in black smoke from several hundred oil refineries. By 1899, Azerbaijan was the world leader in the production and processing of oil. Although at the time it was not Azerbaijan, it was the Baku Governorate of the Caucasus Viceroyalty of the Russian Empire.

For decades, Baku remained Russia’s most important source of oil. During World War II, after the Germans occupied the western side of the North Caucasus, Hitler diverted divisions away from the assault on Stalingrad toward the South Caucasus, reportedly saying, “Unless we get the Baku oil, the war is lost.”

Thomas de Waal related that Hitler’s staff had a cake made for him decorated on top with an outline of the Caspian Sea. “Film footage shows a delighted Hitler taking a slice of the cake, which had the letters B-A-K-U written on it in white icing and chocolate made to look like oil spooned over it.”

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Azerbaijan became an independent nation for the second time. It had been briefly independent after the Russian Empire fell. By then, Baku’s oil production had significantly diminished and the peninsula’s reserves were only expected to last a few decades. But in 1994, a new oil field was found.

By 1999, BP engineers unexpectedly discovered an immense field of natural gas, the largest gas field BP had found in a century. It was estimated to have the potential to keep producing for 40 years. Just like that, Azerbaijan became an exporter of natural gas. Once again, Baku’s economy was booming.

THE 21ST CENTURY

Azerbaijan began the 21st century as a prosperous player on the world stage. From 1994 to 2014, the GDP had grown as if on steroids, from $1.3 billion to $75.2 billion. For several years the economy had the world’s fastest growth rate. Eventually, of course, it began to contract with financial ups and downs since then. An over-reliance on the export of just two products, oil and gas, made the economy vulnerable to instability.

In the meantime, the country developed new pipelines and shipping routes, opened dozens of new embassies, invested abroad, became a non-permanent member of the U.N. Security Council (2012-13), improved its infrastructure, glamorized Baku, and hosted a number of high-profile international events.

While I was in Baku, barriers and fencing were being erected for the Azerbaijan Grand Prix, a Formula 1 race that has become an annual September event. Over the course of four days, 94,000 fans attended the racing action and nightly concerts.

Another byproduct of Baku’s prosperity has been a waning of Russia’s influence. In decades past, Russian was Baku’s lingua franca, as it still is in Bishkek – and to some extent in all of the Central Asian republics. But I met people on the street in Baku every day who spoke little or no Russian.

I later read about a poll that found that 64 percent of Azerbaijan’s population had no basic knowledge of Russian or were beginners. That degree of cultural decolonization would never have been possible without economic independence. Yet ironically, and despite the mutually beneficial relationships with the U.S. and the E.U., Azerbaijan is in the process of rapprochement with Russia.

TRADE PARTNERSHIPS

In August, Vladimir Putin came to Baku. It was his first visit since Azerbaijan’s 2023 lightning-strike-capture of Nagorno-Karabagh (or Karabagh), the ethnic Armenian enclave inside Azerbaijan, which for the last 30 years had been ruled by Armenian separatists. Russia’s “peace-keeping troops” stood down through it all, including the subsequent exodus of virtually all of the ethnic Armenians.

The main talking point for Putin’s visit was his offer to mediate a lasting peace between the two nations. Given Armenia’s sense of betrayal by Russia and Yerevan’s diplomatic shift toward the West, it would have been surprising to see Putin as a peace broker.

But neither Azerbaijan nor Armenia seems interested in having Russia maintain a role in their conflict. Whether or not they can come to peaceful terms remains to be seen, but at least both countries are negotiating without Russia at the table.

Putin’s main agenda almost certainly was not peace-keeping. It was trade routes and investments, because Russia needs Azerbaijan as a transit country for access to world markets. Along with Iran and ports on the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean, Russia also as an indirect route to Western Europe.

It works like this, Baku and Moscow have a “partnership agreement” that predates the Ukraine War. When Western sanctions cut Russia off from European markets, Russian exports of oil and gas to Azerbaijan increased. When winter came, Azerbaijan exported more of its own oil and gas to Europe and met internal needs with Russian imports. The total volume of those exports in both directions has not been large but it has benefited Russia. Sanction evasions like that are happening with other commodities throughout Central Asia as well.

That was why Putin likely headed home to Moscow satisfied. He and President Aliyev announced a number of joint economic ventures. Then Azerbaijan promptly applied to join the BRICS bloc of developing economies. For more than ten years, the only members of the self-selected “outsider’s club” were Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. But in January, Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the United Arab Emirates signed on. Then Azerbaijan applied to join in late August and Türkiye followed suit in September.

AZERBAIJANI ROYALTY

In recent years Azerbaijan has also grown steadily more authoritarian. In 2009, Aliyev held a constitutional referendum to change presidential term limits, enabling him to run for a third term, and then a fourth. In 2016, another referendum created the institution of the vice presidency and Aliyev’s wife, Mehriban Aliyeva, became the first vice president. In February of this year, President Aliyev won yet another term, but this time the main opposition parties did not field candidates and urged their supporters not to vote in a sham election.

In the wake of last year’s victory over Armenia and the run-up to this year’s election, the intimidation and jailing of opposition leaders and journalists intensified. Then on February 1, the European Council of Human Rights voted to suspend the Azerbaijani delegation to its Parliamentary Assembly (PACE), citing the country’s 20-year failure to fulfill “major commitments” and pointing out that “at least 18 journalists and media actors are currently in detention.”

In the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, Thomas de Waal was quoted as saying that Azerbaijan “could easily have fought to stay in the PACE and made a few concessions, but they didn’t. They let that happen to them. And that’s indicative.” In other words, Aliyev was less concerned now with Western pressures about human rights or whether or not Azerbaijan is perceived as a civil society. He is turning toward Russia, Türkiye, and the BRICS alliance.

Of course, when there is an authoritarian government, a wealth of resources and very few checks and balances, corruption and patronage inevitably follow. PASHA Holding is a vast conglomerate spanning banks, hotels, resorts, construction and travel companies, insurance firms, and such. It is presently owned by Aliyev’s two adult daughters.

PASHA Holding’s former CEO and current deputy board chairman is a cousin of the First Lady. Their family is the Pashayevs, the wealthiest family in Azerbaijan. In essence, the Aliyevs and Pashayevs are the country’s royalty, the pinnacle of a steep pyramid of wealth and political power. It is no surprise that Azerbaijan currently ranks 157th out of 180 on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. It shares that rank with Iraq and Myanmar.

On a related note, while riding in a taxi a few miles from Baku’s main business district, I noticed a strange-looking building that looked to me like a slice of grapefruit made of giant bricks. When I asked the driver about it, he smiled and said simply, “Trump.” I then recalled that the Trump Organization had licensed Trump’s name for an “ultra-luxury” Trump Tower in Baku. But the construction was managed by the Mammadovs, a family known for corruption, bribery. and money-laundering.

One Mammadov brother is a member of parliament. Another, who had been the Minister of Transportation, had extensive dealings with an Iranian family involved with the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and was ultimately dismissed by Aliyev for extortion and corruption. In 2015, after Trump announced his first presidential candidacy, U.S. news organizations reported on the Baku tower project, raising questions about the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

The project promptly stalled and was removed from the Trump Organization’s website. Then there was a fire in the building. After Trump was elected in 2016, the Trump Organization cut all ties with the deal. The building stands empty to this day.

FRIENDS ON ALL SIDES

Baku’s failed Trump Tower and Aliyev’s Russian pivot notwithstanding, Azerbaijan does business with various multinational corporations. For example, the AIOC (Azerbaijan International Operating Company) is a consortium of 10 petroleum companies with extraction contracts. Of these, four are from the U.S., two from Japan, and one each from the U.K., Norway, Türkiye, and Azerbaijan.

Current estimates are that Azerbaijan’s oil resources are now just 5 percent of the world’s reserves, but that is not an insignificant amount. On BP’s recent list of countries with oil reserves, Azerbaijan is ranked number 20. On BP’s list of the world’s natural gas reserves, Azerbaijan is number 23, though it has the advantage of a Western-run pipeline connected to Western markets.

Russia, Türkiye, China, and Italy are Azerbaijan’s chief trading partners. But Britain, Belarus, and Georgia are important and, surprisingly, so is Israel. Azerbaijan supplies Israel with some 60 percent of its oil and in return has gotten much of the modern weaponry it used to defeat Armenia. It is little wonder that Azerbaijan maintains a cautious neutrality on the violence in Gaza and on Israel’s conflicts with Hezbollah and Iran.

But Aliyev has friends on all sides. The Azerbaijan-Iran relationship, which for years was somewhat tense, has gotten friendly. In addition to their upcoming BRICS connection, in January the two countries finalized an accord pertaining to the construction of a railway that will fill a gap in the International North-South Transport Corridor (INTSC), a plan to combine road, rail, and maritime routes over 7,000 kilometers to connect St. Petersburg with Mumbai. The INTSC will pass through Azerbaijan and Iran and significantly enhance their trade.

COP29

Baku’s big upcoming event is COP29, the 29th United Nations Climate Change Conference, from November 11 to 22. Every year a different nation hosts the conference, welcoming tens of thousands of participants, along with heads of state and NGOs representing business, the environmental movement, and other sectors. An estimated 50,000 people will come to Baku for this year’s summit, whose primary focus will be how to effectively deliver more climate finance to countries and communities that urgently need it.

There has been criticism over the choice of Baku as the host. Not only because 90% of the country’s export revenues come from fossil fuels, but also because a number of Azerbaijani journalists are still in jail for reporting on in-country climate corruption and environmental crimes.

Also, according to a report released recently by Transparency International and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective, nearly every Baku company named as one of COP29’s “official partners” is owned by the Aliyev family, PASHA Holdings, or one of their associates.

“Official partners” will benefit from exposure to an international audience, access to a special exhibition zone, and sponsorship opportunities. So naturally, it appears to some that President Aliyev simply wants to “greenwash” his country’s global image while his friends and family profit from the occasion.

Aside from what appears to be a scandal regarding the “official partners,” perhaps the COP29 planning committee selected Baku precisely because of the contradictions. Perhaps the choice was meant to send a message to countries that have been less receptive to climate initiatives. Iran, for instance, holds some of the world’s largest deposits of oil and natural gas reserves and still has not signed the Paris Agreement.

Azerbaijan is also the first COP host that was formerly a Soviet republic and, for various reasons, most former Soviet republics have higher levels of air pollution than much of the world.

Aliyev is pragmatic and Baku’s petrocracy has an impending expiration date. Perhaps he is sincere in his stated desire for the country to play a meaningful role in the transition to green energy. It might be wishful thinking, but Azerbaijan could lead by example.

One thing is clear, Baku is an ancient city in the thick of current events.

Aqua Tarkus, Borisb17, Borzywoj, Eti Barname, Hasanov Mikayil, Igor Zuikov, Kadagan, Liseykina/Elena Petrova, Magdalena Paluchowska, Mehdi Kasumov, Mikhail Tereshchenko, Milosz Maslanka, Nurlan Mammadzada, Only Fabrizio, Ruslan K., Rustamli Photos, S. Korodum, Saiko3P, Sergei Mugashev, Studio Loco, Vladimir Zhoga, Vyacheslav Prokofyev, Zulfugar Graphics (via Shutterstock)