While history books call the sIаughtеr that occurred from 1861 to 1865 the “American Civil War,” it is often referred to as the “War to Preserve the Union,” the “War of the Southern Rebellion,” the “War to Make Men Free,” the “War Between the States,” or the “War of Northern Aggression,” depending on the region of the country. What it is not called, but goes to the truth of the conflict, is the “Confederate War for the Preservation of Slavery.”

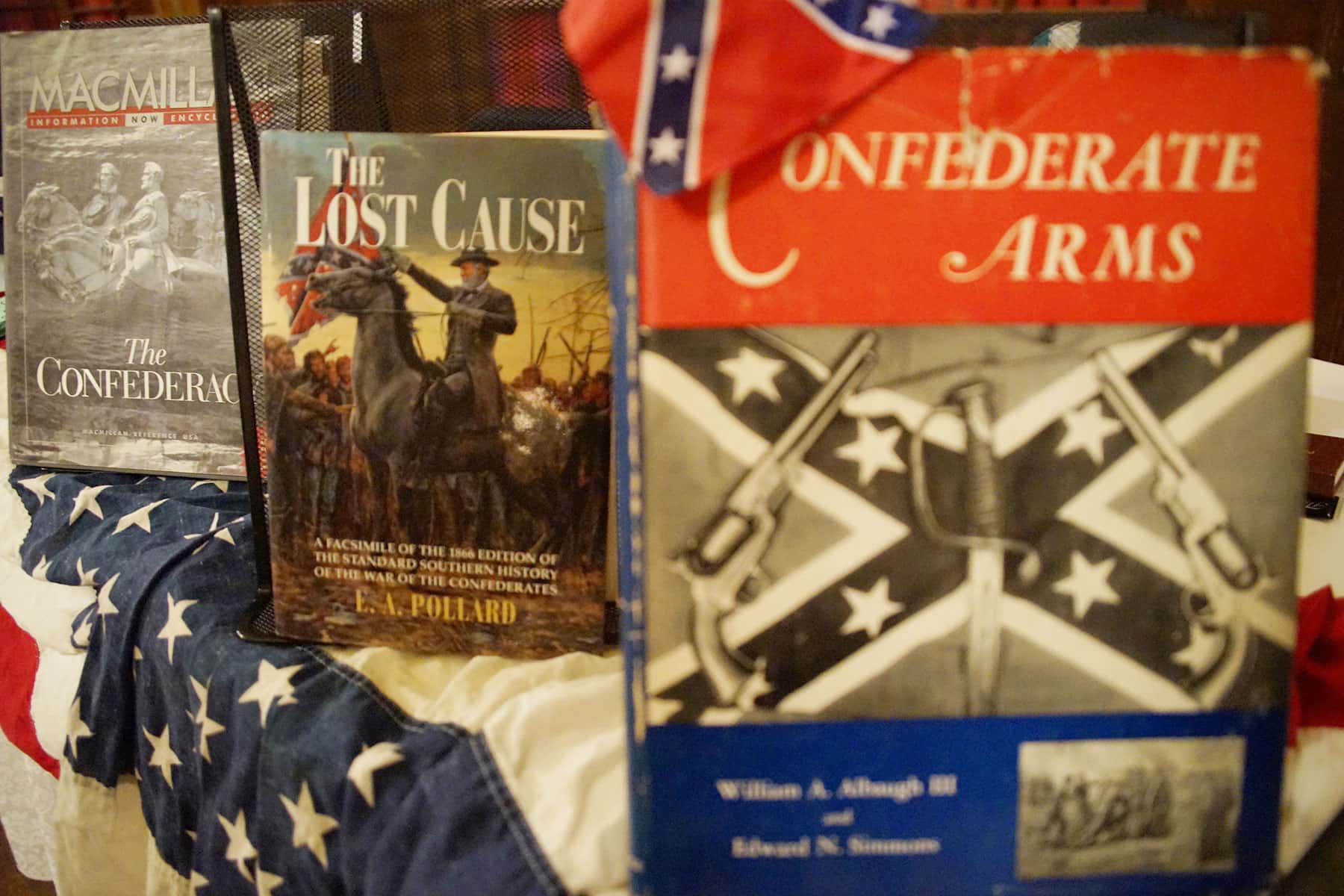

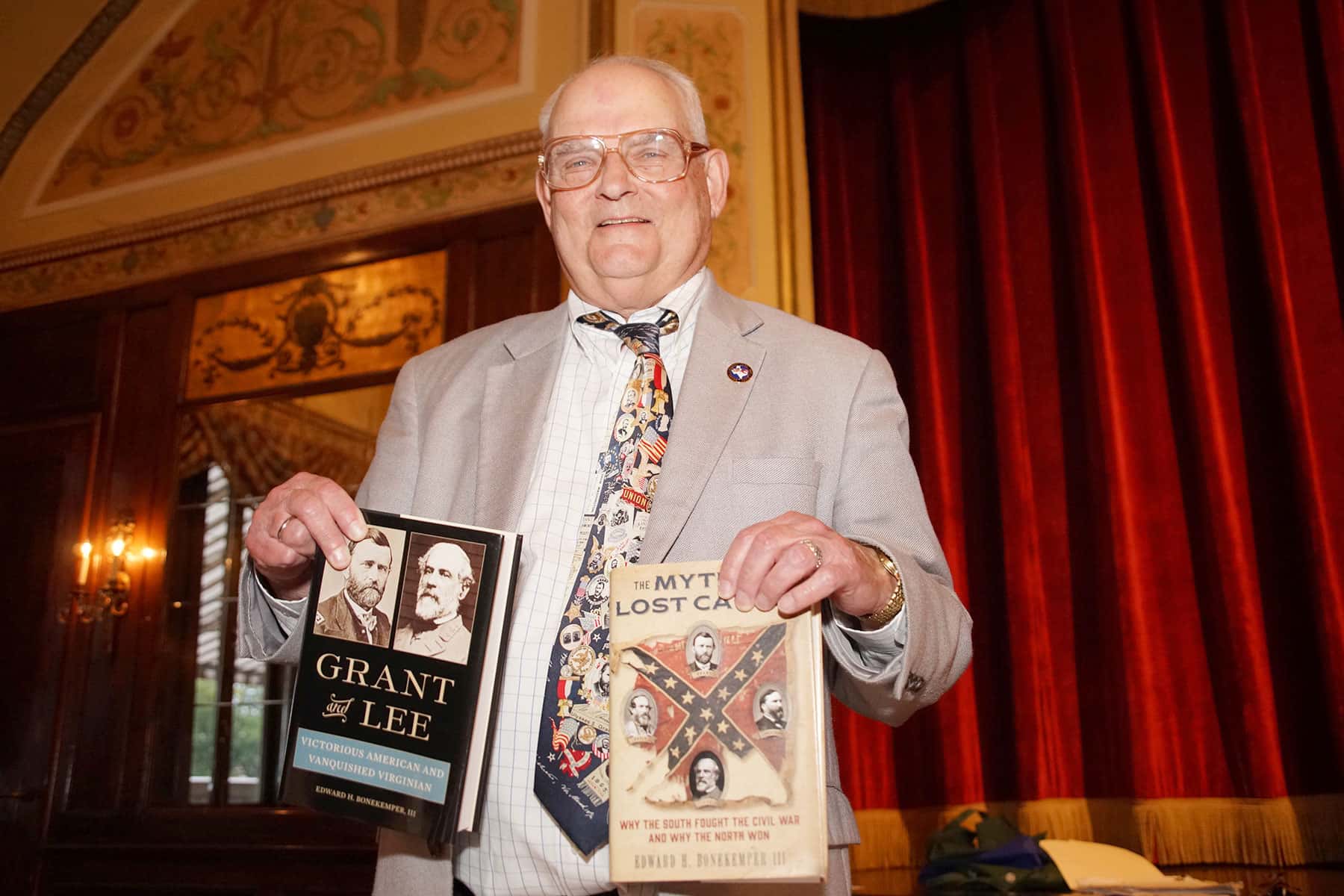

The greatest accomplishment of the Civil War for the Southern soldier was rewriting the account of their loss, a false remembrance known as the Myth of the Lost Cause. As historian Edward H. Bonekemper III describes it, “the narrative is the most successful propaganda campaign in American history.”

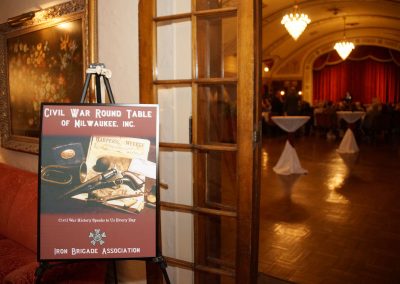

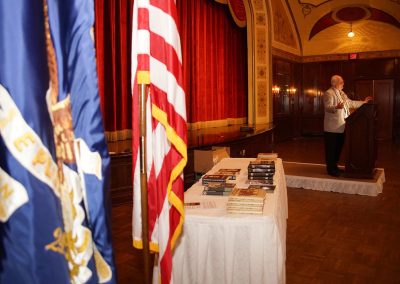

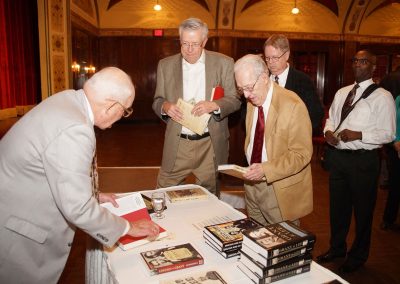

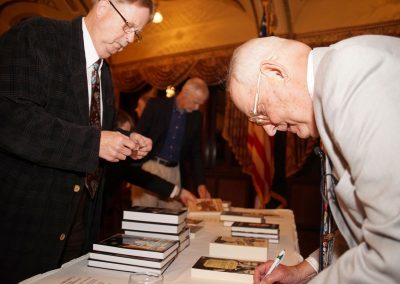

Bonekemper was the keynote speaker at the monthly meeting of the Civil War Round Table of Milwaukee on September 7. The event attracted a record crowd of over one hundred, close to double the usual attendance. Established in 1947, the organization is the second oldest in the world, sharing a common interest in the study, promotion, and recognition of the American Civil War.

“The reason I felt compelled to write the book, The Myth of the Lost Cause: Why the South Fought the Civil War and Why the North Won, was because as I went around the country talking to members of the Civil War Roundtables, I found that a lot of people who should have known better were greatly affected by the false narrative,” said Bonekemper. “That is why I think it is important for all of us to consider what the myth is, and how much we want to buy into that myth.”

The heart of his analysis was whether slavery was the primary cause of secession and the Confederacy’s creation. He examined the Federal protection of slavery, slavery demographics, conventions and declarations of seceding states, their outreach to other slave states, statements by Confederate leaders, the Confederacy’s foreign policy, POW policy, and rejection of black soldiers.

“The strongest evidence of seceders’ motivations is the language they used in their own secession documents. Their reasons included the election of Abraham Lincoln, who opposed extension of slavery into territories; the runaway slave issue; the threat to slavery’s existence – the largest component of Southern wealth; the perceived end of white supremacy and the resultant political and social equality of blacks and whites. Not only did their own secession resolutions reveal slavery and white supremacy as their causation, but the seven states who seceded before Lincoln’s inauguration immediately began an outreach campaign to other slave states. Their correspondence and speeches relied only on slavery-related issues to encourage other slave states to adopt secession.”

After the war, Southerners had a lot to justify. Almost the entire war was fought in the South, and the region was an economic destroyed. Bonekemper examined the accuracy of the Myth and how it has affected the country’s perception of slavery, the rights of states, the nature of the Civil War, and the nature of slavery in 1860, including whether it was a benign and dying institution.

“In terms of slavery disappearing, the estimate of the southerners themselves – in their secession resolutions – was that they were defending an institution which had assets in slaves of $4 to $6 billion. If you categorized assets in the united states, that was the most valuable single category of assets in the united states, the value of slaves. I personally see no indication that slavery was about to go away.”

Drawing on decades of research, Bonekemper also discussed other controversial Myth issues, such as whether the South could have won the Civil War, whether Robert E. Lee was a great general, and whether Ulysses S. Grant was a mere “butcher” who won by brute force.

While there have been rebuttals to Bonekemper’s research, those criticisms either focus on the trivial academic details of historical minutia, or attack his conclusions directly as an example of the need to preserve the Myth itself.

The term “white privilege” that currently occupies the national discussion is often presented as a modern development. However, the condition is as old as slavery, and Bonekemper offered a 150 year old perspective to the current debate.

“Even if you did not personally own or someone in your family did not personally own slaves, you were still the social beneficiary of the existence of slavery. No matter how poor you may be, you always knew that in your society, there were 4 million people who were inferior to you as a matter of law and of social practice.”

The Confederacy’s defeat ended slavery and kept America from being an international pariah. It also resulted in passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th constitutional amendments; these provided the legal basis for ending legal segregation and providing blacks with voting and other civil rights – after a hundred years of Jim Crow laws and nationwide segregation.

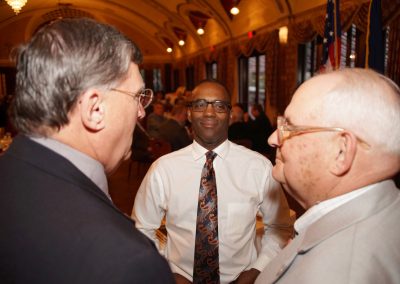

“Bonekemper confirmed what I’ve argued for years about the myth of the Civil War being about state’s rights,” said community leader and historian Reggie Jackson. “He provided clear, irrefutable evidence to argue that it was all about slavery. I really enjoyed the lecture and can’t wait to read his book.”

Edward H. Bonekemper III is a military historian, teacher, and celebrated author. He writes frequently about slavery, the American Civil War, and Union and Confederate generals. Bonekemper speaks to Civil War Roundtables across the nation and lectures at the Smithsonian Institution.