Milwaukee-native Dontre Hamilton was 31 years-old at the time of his death, which came on April 30, 2014 when he was shot by police officer Christopher Manney at Red Arrow Park downtown.

The social justice protests that erupted after Dontre’s death brought renewed awareness to the Milwaukee public about the issue of police brutality directed at Blacks in the community. The daily marches, nightly vigils at Red Arrow Park, and calls for Police reform foreshadowed what would follow in 2016 with the death of Sylville Smith in the Sherman Park neighborhood, and the explosive national reaction to George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis.

No charges were ever brought against Manney, but he was fired from the Milwaukee Police Department. Law enforcement officers were then equipped with body cameras after the incident.

But since that fateful night, Red Arrow Park’s identity has been irreversibly interwoven and identified with Dontre Hamilton. Alderman Khalif Rainey, who was a Milwaukee County Board Supervisor in 2015, pushed to rename the park in his memory.

The effort to rename the park was halted after complaints from veterans, and pressure from veterans groups. As far as the general public was concerned the idea had faded away by 2016. But after every incident of police violence or racial injustice, “Dontre Hamilton Park” was the epicenter for nearly every rally or protest march through downtown Milwaukee. It also hosted “Dontre Day” each year to remember his death.

With a rekindled public interest due to the social unrest over the summer, it is worth re-examining the situation for why renaming the park makes sense in 2020, and what adjustments could help make it a reality.

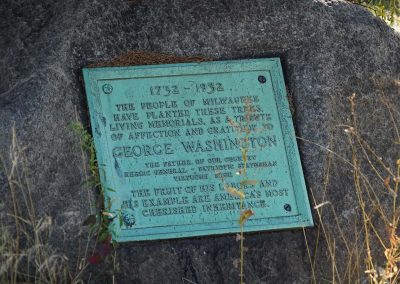

“Milwaukee has always considered park names open to change. The strip of greenery in the median in front of Central Library, for instance, was once Washington Park. The present-day Washington Park was originally West Park. Pere Marquette Park is along the downtown riverfront, formerly it was several blocks south and in front of the Milwaukee Road station. The station is gone, but there is still a park – now called Zeidler Union Square.” – Carl Swanson, “Lost Milwaukee“

According to Swanson, Red Arrow Park has had a very strange history. It was originally located between 10th and 11th streets on Wisconsin Avenue, across the street and to the west of the Central Library. The land was once James Kneeland’s estate, before being bulldozed in mid-1960s to make way for the Marquette Interchange.

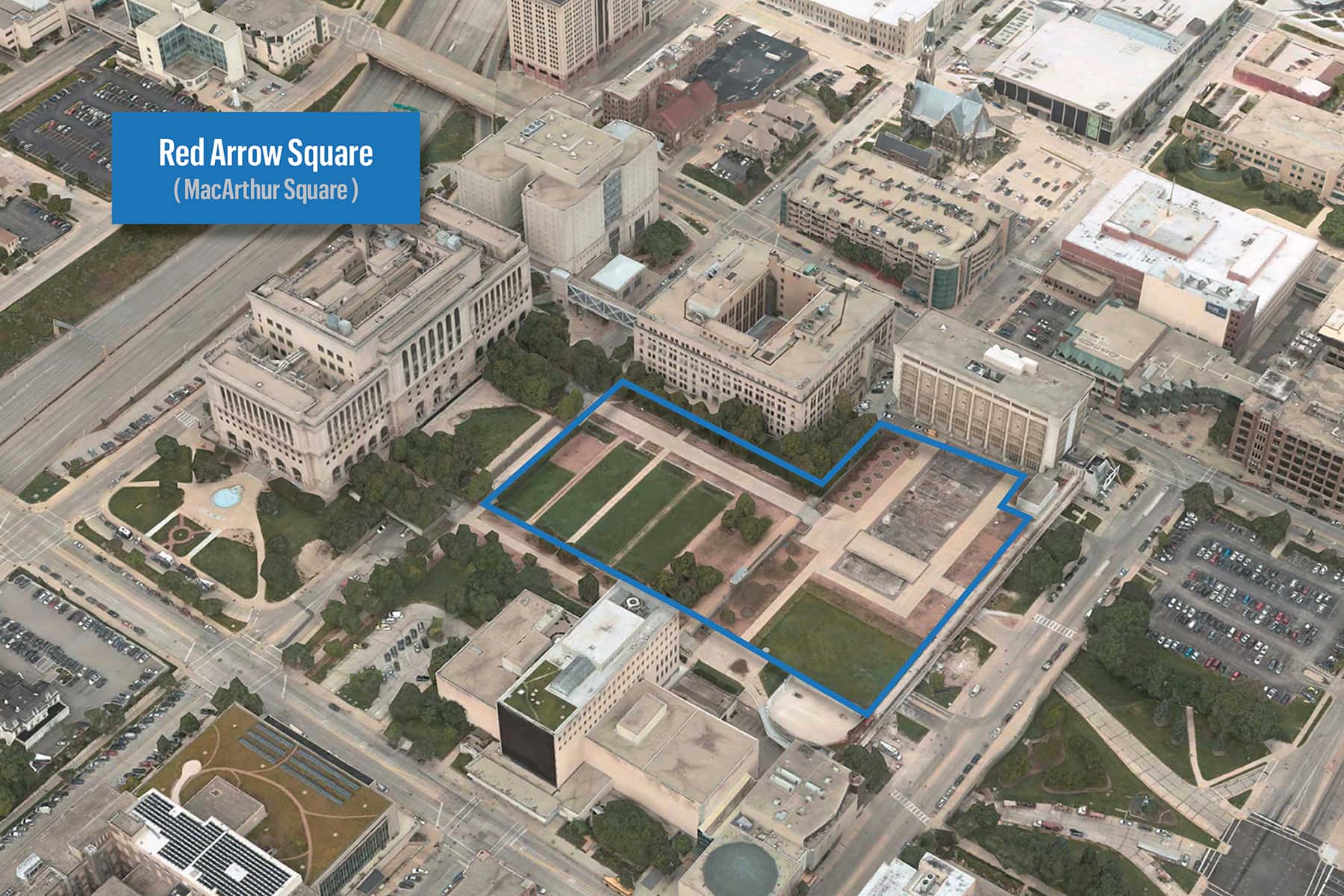

Present day Red Arrow Park, north of City Hall on Water Street, is located on land that was once part of the site of Kitty William’s brothel, and later a much needed parking lot for city employees.

The park was given a name that was on the minds of Milwaukee residents in the years immediately following the First World War. Army National Guard soldiers from Milwaukee were mobilized to form the U.S. Army’s 32nd Division and sent to France. Fighting for six months with only 10 rest days, the division suffered more than 14,000 casualties. On October 4, 1918, after nearly a week of fighting north of the Argonne forest, the division’s soldiers became the first to break through the heavily fortified Hindenberg Line.

Soldiers of the 32nd Division wear a shoulder patch honoring the tenacious fight in the Argonne. The insignia is a line shot through with a red arrow signifying the piercing of every battle line the enemy placed before it. Local veteran organizations raised funds to place a granite monument there in the shape of that emblem.

The second location for Red Arrow Park was completed in 1970. It was instantly despised as being poorly designed and a waste of the public’s money. The 1999 addition of $2.4 million outdoor skating rink was also highly controversial with veterans. The plan was opposed by retired Colonel Thomas J. Makal Sr., formerly of the 32nd Division, who said that “this hallowed memorial park dedicated to the men who served in the famous division is no place to have a skating rink. Such a use will degrade its memorial purpose.”

In addition to the established precedent of renaming parks and moving them, Milwaukee has also previously relocated statues memorializing veterans and other honored individuals. Several of the statues on Wisconsin Avenue, across from the Central Library, were erected elsewhere originally. The “Court of Honor” saw major additions and relocations between 1898 and 1932. Another well known military monument was moved even more recently.

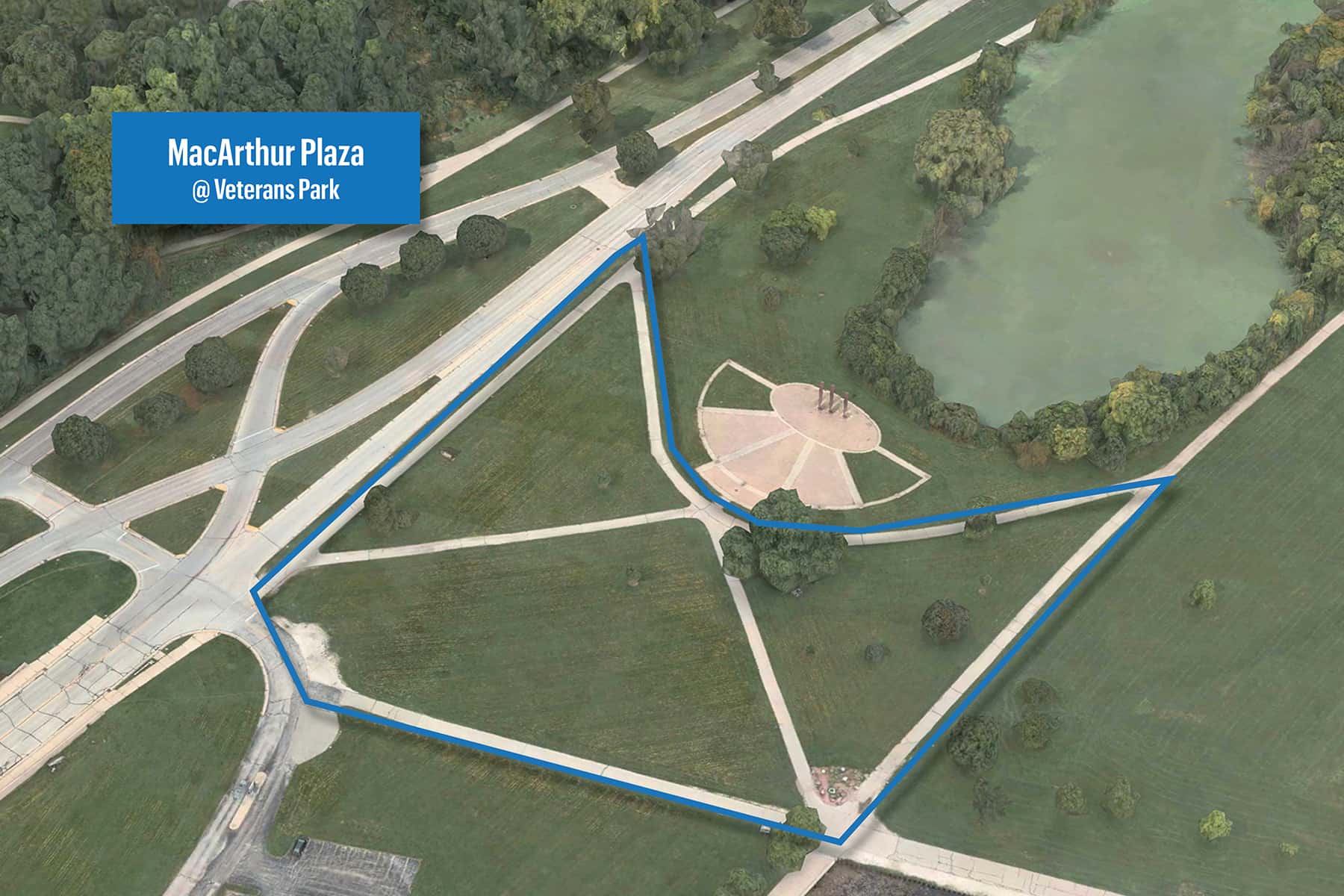

Nearly 35 years after its original dedication on June 8, 1979, the statue of General Douglas MacArthur was taken from its location by the County Courthouse and installed at Veterans Park. In 2014, veterans felt that the 9-foot bronze statue of the famous general and Milwaukee-native was not getting the attention it deserved and petitioned to have it moved. It was rededicated on June 7, 2014, facing the War Memorial Center and Lake Michigan, in a prominent spot that is now an iconic part of the lakefront’s landscape.

MacArthur Square retains its namesake, but little else. In light of that condition, it has been suggested that the Red Arrow monument should be moved to the location. Under the unofficial proposal being floated for consideration, several of the issues pertaining to the mentioned locations could be resolved.

It would begin by annexing the immediate area around the statue of General Douglas MacArthur and designating the space as “MacArthur Plaza” at Veterans Park. Then the Red Arrow monument would be moved to MacArthur Square, with that location being renamed “Red Arrow Square.” And finally, Red Arrow Park would accept the official name of “Dontre Hamilton Park.”

The new “Red Arrow Square” would be an upgrade in size and location, and carrying on the tradition of its previous military honors. It would also offer a connection to the memorial for fallen Milwaukee police officers that was installed on the grounds.

It is understandable that the new relocation idea would meet with the same resistance as the previous effort. But it should be remembered that symbols change and are often appropriated, against the wishes of their creators. Daniel Decatur Emmett wrote “Dixie” as a song for minstrel shows that were performed in the North, for example, but it later became the de facto national anthem of the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Relocating Red Arrow Park would restore the intention of memorializing those war veterans. It would also free their memory from the cloud of controversy surrounding Dontre’s death, and offer distance from an epicenter for responding to civil unrest issues.

The Red Arrow monument would also not need to compete with another memorial. Even though the park’s renaming was not approved, a physical memorial to Dontre was. Its design and installation has been delayed, but at some point soon there will be a monument erected to his young life. And for anyone interested in preserving the park’s name and its red granite symbol, a fixed memorial to the racially-triggered death of a young black man in the nation’s most segregated city a few feet away would cast a wide shadow. Eventually it should be expected that Dontre’s memorial would become the dominant feature of the public space.

The issue remains in the hands of public officials at city and county levels, veterans groups, and stakeholders – like Maria Hamilton and her social justice advocacy organization, to come to an agreement and push the initiative forward.

© Photo

Lee Matz