The end of 2019 inauspiciously brought the seventy-fifth anniversary of Korematsu v. United States, the United States Supreme Court decision affirming the wartime, race-based internment of more than 120,000 persons of Japanese descent, two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens.

While the notorious 1944 Korematsu v. United States[i] decision is decades old, its core concerns haunted 2019, the executive orders allowing mass internment, national interest decision-making based on race, government reparations, and citizenship stats and the counting of persons. Recent court decisions have turned back executive orders requiring the ban of certain foreign-born persons and the registration of others; have curbed some restrictions included in executive orders regarding refugee and immigrant border camps, “zero-tolerance” entry, and family separation; and have excluded an executive branch department from adding a question about citizenship on the 2020 census form.

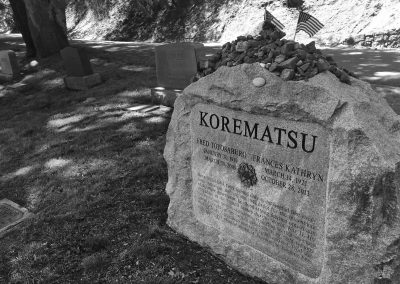

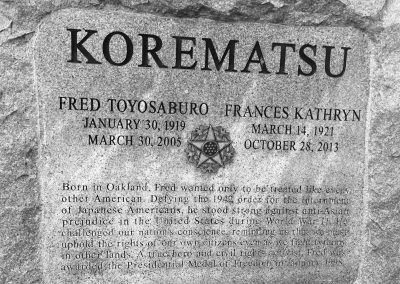

The landmark case’s defendant, Fred Korematsu, was a United States citizen whose parents were Japanese immigrants; he fought and lost his two-year legal battle to maintain his Constitutionally-guaranteed liberty, property, and civil rights— all denied him based solely on his race. Considered among the most important cases on war powers, Korematsu is also considered by scholars and practitioners alike as one of the most misguided of constitutional decisions ever constructed. For 74 years it stood as controlling authority until 2018, when U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts concluded that “[t]he forcible relocation of U.S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race, is objectively unlawful and outside the scope of Presidential authority.”[ii]

Besides race-based internment, Korematsu’s specter also arose throughout the 2019 debate about legislation urging a Congressionally-created “Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act.”[iii] The discussions frequently referenced the 1988 law awarding government reparations to surviving WWII internees of Japanese descent. In 1988, Congress, in an extraordinary act, appropriated $20,000 to each of the then 60,000 surviving internees. However, an even more extraordinary act, was the apology included in the reparation law, delivered by President Ronald Reagan on behalf of the nation. Upon signing the reparations bill he declared “Here we admit a wrong. Here we reaffirm our commitment as a nation to equal justice under law.”[iv]

The renewed effort for African-American Reparations came during the observance of the 2019 quadricentennial anniversary of the first arrival in 1619 of enslaved Africans in America. About 170 later African- Americans would be counted officially though not entirely in a United States Census. African-Americans, labeled as property, were not recognized as persons until the Constitutional Congress agreed to the Constitutional clause that three out of five slaves would be counted in the decennial census — for representation and taxation purposes. [v] The 1870 census is the first time that the U.S. Census included African-Americans as “counting the whole number of persons in each State.”[vi]

As the 2020 census looms, it does so in the shadow of Korematsu. Yet, despite the indignities and hardships suffered by the more than 120,000 occupants of the Japanese Internment Camps, each of them – as citizens or as foreign-born persons— were included in the U.S. Census counts of 1940 and of 1950 as persons. The U.S. Constitution calls again in 2020 for each person to be counted – regardless of legal status, homelessness, age, or voting status.

As Mayor Tom Barrett declared at the October 2019 Kick-Off of the Greater Milwaukee Complete Count Committee, “Census data is critical to our families’ futures and the next generation. The more people we count means more federal money [allocated to Milwaukee] and fairer elections.”

Korematsu v. United States: The backstory and the aftermath

In February 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued an executive order authorizing the armed forces under the Secretary of War to designate military areas and, in turn, to seize and remove without any distinction of wrong doing or any other basis persons of Japanese ancestry. The newly declared war fueled fears of espionage and treason after the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The unmitigated removal resulted in unplanned mass relocation. Eighteen “temporary civilian camps” were contrived to house thousands of seized persons and families while “permanent” internment camps were constructed as self-contained “cities,” remotely situated in seven western states. With displacement came the resultant domino effects of the seizure of internees’ property, the surrender to a barbed-wire-fenced existence including forced labor, and the stripping of all civil and voting rights.

Korematsu refused to leave his home in the exclusion zones, in violation of Roosevelt’s executive order. To underscore his Korematsu’s defiance, he underwent plastic surgery to alter Japanese facial features, changed his name, and claimed different racial identities. Upon arrest for violating the executive order, he underwent trial, suffered conviction, and the pursued an appeal of that conviction.

Six U.S. Supreme Court justices in Korematsu v. United States decided that the internment was not race-based but rather was a “military necessity.” The executive branch ordered removal; the legislative branch funded the mass relocation; and the judicial branch upheld both the removal and relocation “because the properly constituted military authorities… decided that the military urgency of the situation demanded that all citizens of Japanese ancestry be segregated from the West Coast.” Three justices wrote vehement dissents. They opined that Korematsu was convicted of the act “merely of being present in the state whereof he is a citizen, near the place where he was born, and where all his life he has lived” and that wartime concerns were not sufficient to deprive the internees of constitutionally protected civil rights. They called the executive order “the legalization of racism” resulting in the internees’ rights “fall[ing] into the ugly abyss of racism.” They asserted that the executive order mimicked the “abhorrent and despicable treatment of minority groups by the dictatorial tyrannies which this nation is now pledged to destroy.”

After affirming Korematsu’s conviction, the defendant was sent to a Utah camp with his family, consigned to forced labor for just over another year. In 1983, a California federal court overturned Korematsu’s conviction. The court reviewed newly found evidence of prosecutorial misconduct in 1942 and vacated the decades-old conviction. But the underlying legal precedent established by the 1944 case remained in force—until the 2018 Trump v. Hawaii decision.

In response to another executive order requiring “Muslim registration,” Chief Justice Roberts wrote in the majority opinion dictum that Korematsu was wrongly decided. The Trump v. Hawaii opinion essentially indicates that a majority of the court no longer finds Korematsu persuasive. Chief Justice Roberts quoted Justice Robert H. Jackson’s dissent from Korematsu:

“The dissent’s reference to Korematsu, however, affords this Court the opportunity to make express what is already obvious: Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—’has no place in law under the Constitution.’”

Chief Justice Roberts concluded that “[t]he forcible relocation of U.S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race, is objectively unlawful and outside the scope of Presidential authority.”

- [i] 323 U.S. 214 (1944). Issued December 18, 1944.

- [ii] Trump v. Hawaii, 138 S. Ct. 2392 (2018). (quoting 323 U.S., at 248 (Jackson, J., dissenting).

- [iii] H.R.40 116th Congress (2019-2020)

- [iv] Civil Liberties Act of 1988 (Pub.L. 100–383, title I, August 10, 1988, 102 Stat. 904, 50a U.S.C. § 1989b et seq.)

- [v] United States Constitution, Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3.

- [vi] Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) which explicitly repealed the 3/5th Compromise of the United States Constitution Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3.

Library of Congress