Feeling on edge since January, “Sarah” knew it was only a matter of time before COVID-19 arrived in the United States, and because of the vitriolic political climate it would be Chinese-Americans like her who would get blamed for it.

Fast forward to mid-March, NPR coronavirus news played over the office speakers when Sarah’s boss said to her, “If your people hadn’t eaten bats, then this wouldn’t have happened.”

“It was like a joking anger,” said Sarah, who works in Milwaukee. “I just walked away. I was nervous. He said it pretty loudly, kind of aggressively.”

Targeted because of their race, Chinese-Americans and other Asians of different ethnicities have been physically and verbally attacked across the nation for the misperception that they brought COVID-19 to the United States.

Between March 19 and April 2, there have been more than 1100 reports of coronavirus discrimination against Asian-Americans living throughout the United States, according to the STOP AAPI HATE reporting center. Individuals reported anti-Asian incidents to the website a3pcon.org/stopaapihate, an effort started by the Asian Pacific Planning and Policy Council, Chinese for Affirmative Action, and the San Francisco State University Asian American Studies Department.

“It really bothers me,” Sarah said about the remark from her boss. “I try not to think about it, and just focus on what I can do.”

Sarah did not want to use her real name because she was afraid of losing her job in retaliation for making a public statement.

As local media coverage of COVID-19 ramped up in March, Sue, who is Hmong-American, prepared herself to get dirty looks. Sue never thought someone would say to her in a grocery store, “I don’t want you to spit the virus on my stuff.”

Sue, who also chose to withhold her real name for fear of reprisals, stood in a grocery check-out line in mid-March at a Milwaukee store when a woman came from the back of the line and yelled, “Excuse me. Excuse me. Excuse me.” Sue looked up from her phone. The woman budged in front of her and said, “Yeah I’m talking to you. I need you to move six feet away from me. You know what I’m talking about. I don’t want you anywhere near me.”

Then it hit Sue. This was a racial attack. In an even tone, Sue told the woman, “You’re being very ignorant right now.”

As Sue began putting her items on the conveyor belt, the woman became angrier and told Sue to take her items off. The woman did not want Sue’s items to touch her food. She told Sue she did not want Sue to spit the virus on her stuff.

The woman’s daughter attempted to defuse the situation, and apologized to Sue for the outburst. But the woman continued taunting Sue. Finally an employee removed the woman from the line after Sue asked for the store to deal with the situation.

With her purchase complete, Sue noticed an older Hmong couple making a purchase. She waited nearby to make sure that they proceed safely through the checkout. When Sue finally did leave the store, she was shaking.

“I just get really heated every time I think about it,” Sue said in a phone interview.

She views herself as a strong person, but after the incident, Sue said, “I get palpitations. I’m anxious. Everywhere I go, I’m just constantly on guard to see who’s looking at me differently.”

The outspoken woman had no idea Sue was a nurse. Sue treats patients regardless of race, belief, and background. For those who target Asian-Americans, they may attack someone who could take care of them later, Sue pointed out.

Within the same timeframe of Sarah and Sue’s encounters, President Trump called the coronavirus the “Chinese Virus” despite criticism that assigning the virus to a specific ethnicity was racist.

Five days later on March 23, Trump tweeted, “It is very important that we totally protect our Asian American community in the United States, and all around the world.”

The City of Milwaukee Equal Rights Commission issued a statement on March 19, saying:

“The ERC is aware of disturbing incidents of discrimination – based on unfounded xenophobic fears – directed at Asian communities, particularly in Chinese communities in other cities. Anxiety and fear surrounding any outbreak or incident should never be a reason to discriminate against any group or individual. We stand for equal rights for all people and warn the public to not stigmatize people based on race, national origin, age, health condition, or disability.”

At 12:20 am on March 21, Lucky Liu’s restaurant, which serves Chinese and Japanese cuisine in Milwaukee, announced on Facebook it was closing because of xenophobic attacks.

“Since the COVID-19 crisis is spreading intensively around Milwaukee along with the racial tensions we are experiencing ever since then, we have encountered more xenophobic and verbal attacks toward our committed staff members,” a post said. “For the safety and well-being of our staffs, our team has come to a difficult decision in closing the business temporarily until further notice. Thank you for understanding and we hope that everyone will rise out of the pandemic strong. Stay safe and healthy.”

By 5:40 pm that day, Lucky’s Liu’s owners said in another post:

“We are EXTREMELY overwhelmed by everyone’s warm thoughts, loving support, and prayers. Many have even offered various forms of donations and financial aid and we are deeply grateful for everyone’s kind gestures. To convey our gratitude, our family would like to instead, pass on this act of kindness.”

Lucky Liu’s later donated produce to the public. The owners did not respond for comment.

May yer Thao, who is Hmong-American, has not experienced coronavirus-related racism yet. But she is on guard, wondering what she would do if another person were to be aggressive with her.

“It’s such an emotional thing,” Thao said. “It’s in the heat of the moment. All of a sudden you can become paralyzed. That’s something I’m preparing for: mustering up the courage to say what I need to say in response.”

Thao and three other co-founders of ElevAsian, an informal young professional organization for Milwaukee-based Asian Americans, had a virtual meeting with Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett on March 26 to talk about the growing backlash against local Asian communities. ElevAsian members work to raise the visibility of the Asian-American community in Milwaukee and advocate for related issues, Thao explained.

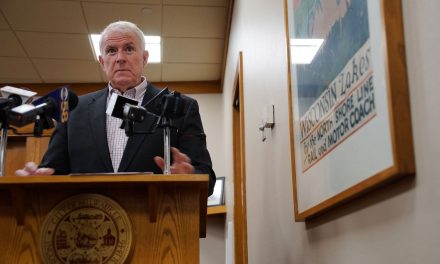

Barrett said in a statement issued that day:

“The World Health Organization has urged people to be careful with language used to describe COVID-19, insisting that it not be referred to as the ‘Chinese’ or ‘Wuhan’ virus. In this time of heightening tensions, there are serious concerns in the Asian American community about scapegoating and becoming the targets of misplaced fear and anger. I oppose any expressions of racism and xenophobia at all levels. No one should live in fear because of who they are, what they look like, or where they come from. This virus knows no borders. It’s wisest to use official names for this pandemic, especially if there is potential to do harm.”

The group’s co-founders were thankful for Barrett’s message of support.

“We need others to stand up for us as allies,” said ElevAsian co-founder Shary Tran, who is Vietnamese-American.

“Pointing fingers, trying to blame anyone for what’s happening to our country is not going to help us overcome the crisis we’re in,” Tran said. “It’s about behaviors. It’s about being safe. It’s about being mindful about social distancing. That’s what we should be concerned about.”

Language is important.

“I think we need to be intentional with the language and the messaging and not stigmatize the virus to Asian American Pacific Islanders,” said ElevAsian co-founder Erik Kennedy, a Korean adoptee. “We need to really use the correct term of COVID-19.”

On March 24, chalk messages saying, “IT’S FROM CHINA #CHINESEVIRUS” and (expletive) THE CHINESE GOVERNMENT” were found on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus.

Pointing out that a pandemic has no nationality or race, the UW-Madison Asian American Studies program posted photos of the chalk messages on its Facebook page. The university also condemned the messages in a statement:

“We want to be clear that racist behaviors or stereotyping of any kind are not tolerated at UW–Madison—no matter if we are online, passing others in public, or quarantined at home.”

The Marathon County Sheriff’s Office have reported verbal and physical attacks, as well as vandalism and stolen property against Hmong-Americans. Marathon County Sheriff Scott Parks said he found the reports disturbing.

“For those persons who have elected to behave in this fashion, rest assured that Marathon County law enforcement is diligently working on these investigations and will seek prosecution for the criminal acts,” Parks said in a statement. “For those persons who have been victimized, I want to apologize to you, because this is not how a majority of Marathon County residents act.”

Wisconsin Attorney General Josh Kaul added his voice in condemning actions that targeted state residents of Asian descent on April 2. He outlined Wisconsin’s Hate Crime provisions under Statute § 939.645, that can apply as a penalty enhancer when certain crimes are committed based on a “belief or perception regarding the race, religion, color, disability, sexual orientation, national origin or ancestry of” the victim.

“I had the opportunity to talk to community leaders who are working to raise awareness about recent acts of discrimination against members of the Asian-American/Pacific Islander community and who are taking action to fight discrimination,” said AG Kaul. “We must stand together and speak out against racism and xenophobia.”

Milwaukee residents of Asian ethnicity are encouraged to contact the City of Milwaukee Equal Rights Commission at at erc@milwaukee.gov if they have encountered discrimination, or know someone who has, related to COVID-19. Asian Americans can also report anti-Asian incidents related to COVID-19 to the STOP AAPI HATE reporting center. The reporting center is trying compile a national database during the pandemic.