Refugees who make a new home in Wisconsin carry with them hopes and dreams as diverse as their backgrounds. But many find upon arrival that their education and career goals do not necessarily align with the government’s refugee resettlement program.

The paramount and singular goal of refugee resettlement in the United States is for refugees to secure rapid economic “self-sufficiency,” as measured by employment and transition off support services. The way the federal government defines this goal significantly limits how refugee resettlement providers are able to support higher education opportunities for refugees in Wisconsin.

College education for refugees, as one resettlement service provider in Wisconsin explained, “is really hard. There are a lot of challenges. So I would say that for adults the reality is, you need to work.”

Another resettlement service provider in Wisconsin explained that in terms of federal policy, “success” is characterized by the speed in which refugees transition off of social services.

“You are expected to get a job as soon as possible,” they said. “And that sometimes is very demoralizing for people, that they had a lot of hopes and dreams of opportunity here, and the first thing you have to tell them is, “‘Sorry, the goal of you being here is to get a job first thing. It’s not to go to school, it’s not to get a degree.'”

There is an assumption among both researchers and refugee resettlement providers that the socioeconomic barriers refugees face are so high, and the need for emergency food, health and housing along with basic employment services is so great, that college and professional post-graduation employment is an overly optimistic, even utopian goal.

It is true that the overwhelming majority of refugees coming to the U.S. typically require, and sometimes struggle to access, basic services. But it is also the case that many refugees come to the U.S. with some college background, and others come with a goal of going to college and manage to achieve that ambition despite the obstacles they face.

Some refugees arrive in Wisconsin with college credits, degrees or professional credentials acquired prior to displacement, or as a refugee in a nearby country. With the protracted nature of modern conflicts, where people may be displaced for many years — and in some cases, decades — some refugees use that time to attend college and obtain educational and professional credentials.

However, upon resettlement in Wisconsin, refugees face serious obstacles with the recognition of those credentials. Colleges and universities require “official” copies of transcripts and other educational documents in applications for admission. Often, refugees lack the needed documentation to support such applications.

Further, on occasion, colleges in the nation of origin may be destroyed or not recognized by higher education accrediting agencies in the United States. Refugee resettlement providers refer such cases to private credentialing specialists, who review the available documentation and produce a report that identifies credentials that enrollment officers may approve. In some cases, credentialing specialists work with refugees and their former educational institutions abroad to track down missing documentation. Often, though, this is impossible.

In such cases, refugees can employ a “narrative approach.” This process involves describing the educational background of the refugee as best as possible, to try to fill in the gaps left by uncertain documentation. Ultimately, the decision to recognize a refugee’s credentials is in the hands of enrollment officers of the particular institution. Often, they do not recognize the credentials as equivalent, or rule the application as “incomplete” because of the unofficial status of the transcripts.

Other barriers that refugees face to access higher education include poverty and a lack of affordable housing, struggles with learning academic English, challenges associated with cultural differences in educational settings and a lack of knowledge for how to prepare, access and finance higher education. The adjustment to such social, economic and cultural differences can be bewildering for new refugees.

As one service provider explained: “I think it depends on how educated the people are when they arrive. You know, how much adjustment they have … it’s such a huge adjustment just to be here and start life here, to think about going to college or going to the technical college or adding anything to your plate, I think it’s, you know, unrealistic.”

The University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Center for Research on College-Workforce Transition is investigating the barriers and pathways to college success for refugees within the state. This work has included interviewing resettlement providers and educators in Wisconsin about their work to support higher education for refugees. It has subsequently turned to interviewing refugees with college experiences and goals in communities around the state.

While resettlement service providers and educators work hard to support the college attainment of refugees in communities around Wisconsin, the Center is finding that the narrowly defined goal of refugee resettlement as “self-sufficiency” and the highly structured and time-limited nature of the resettlement process effectively thwart and complicate this goal.

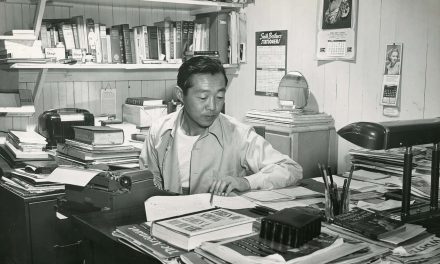

Yet, there is evidence that a more robust resettlement and social services support system can facilitate access to higher education. Exemplifying this potential is the story of a Hmong refugee who came to Wisconsin as a young woman, resettled into a rural community in the Fox Valley, and graduated high school and college. She eventually became a leader in the Hmong community and a social service provider for refugees in Wisconsin.

As both a former refugee, and now as a provider of services to refugees in Wisconsin, she was able to reflect on the impact of changing federal and local support for refugees to resettle and access education over the past decade, and increasingly today.

Like I always say, “I’m a product of, you know, the food stamp,” and I’m proud to say that because of that support I’m able to concentrate and do what I do, right? And get out of the system, and become on the other side, and contributing it back. But for refugees who come right now, that piece is kind of, like, being policed so heavily that you don’t have that sense of pride that you’re being supported, that you are being embraced. But you’re, you know, coming, and becoming, you know, a burden. So I think that feeling has changed, and I think if I’m now coming in as a refugee, I think it’d be hard to, you know, integrate with not having, you know, an environment for you to truly focus on developing yourself, because you have to work. … And so, I think that honeymoon stage for refugees is not there anymore, compared to during our time, where I feel like we have a honeymoon stage where our sponsor and the people around us who knew us gave us that shelter to develop ourselves. But now, I feel like there’s no honeymoon stage for refugees at all.

Resettlement service providers can support refugees’ higher education goals by connecting them with advisors, educators and community members, as well as to pre-college and college support services. Refugee advocacy and support groups such as Open Doors for Refugees and the Literacy Network generally supports efforts by refugees to advance their college and career goals.

One Somali refugee, for example, moved her family from another area of the state where they were resettled, in order to attend Madison College. There, she and other refugees have found supportive advisors and faculty, and ultimately, college and career success.

In spite of such valuable and effective resources in the community, more basic economic constraints remain a serious problem, such as a local lack of affordable housing. With Madison’s high and escalating rents and low vacancy rate, one of the city’s two refugee agencies halted resettlement at the beginning of 2019. This type of issue limits the opportunities of refugees to be resettled in close proximity to the very resources that can support their college and career success.

Editor’s note: Sources have not been identified in this story due to research ethics requirements.

Matthew Wolfgram and Isabella Vang

Madison College and UW-Whitewater

Originally published on WisContext.org, which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.