Why is it so hard for white people to talk about racism? It is a question posed by the white academic Robin DiAngelo, whose book “White Fragility” has spent seven months hovering at the top end of the New York Times bestseller list.

“The problem with white people,” she says, “is that they just don’t listen. In my experience, day in and day out, most white people are absolutely not receptive to finding out their impact on other people. There is a refusal to know or see, or to listen or hear, or to validate.”

As a sociologist, she has worked as a diversity trainer across the US for more than 20 years and has a PhD in multicultural education. More recently, however, she has received abuse and criticism for starting a conversation that she felt “my people were not having”. “I got a death threat recently that called me a bully, and I thought, ‘Wow, do you not see the irony here? You just threatened to kill me over some words that I say.’”

But, of course, DiAngelo’s words provoke. They cause discomfort and defensiveness. She picks at the disbelief and sensitivity white people exhibit when they are told they are complicit in society’s institutional racism. She challenges rather than gives solutions. Her book is a harsh wake-up call for white liberals, who she thinks could be much more progressive if they first listened.

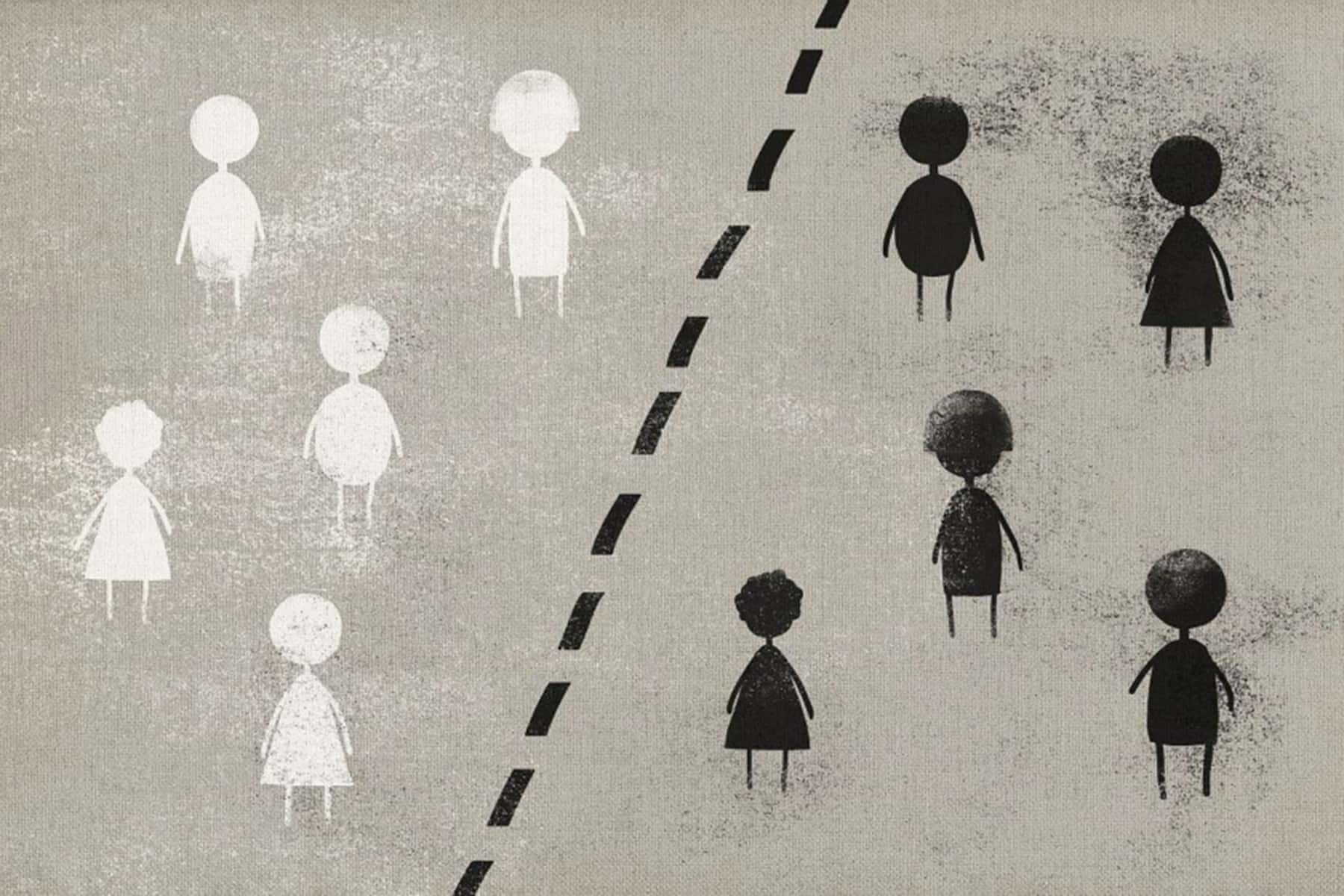

DiAngelo says she encounters a lot of “certitude from white people – they insist ‘Well, it’s not me’, or say ‘I’m doing my best, what do you want from me?’” She defines this as white fragility – the inability of white people to tolerate racial stress. This, she says, leads to white people “weaponizing their hurt feelings” and being indignant and defensive when confronted with racial inequality and injustice. This creates a climate where the suggestion or accusation of racism causes more outrage among white people than the racism itself. “And if nobody is racist,” she asks, “why is racism still America’s biggest problem? What are white people afraid they will lose by listening? What is so threatening about humility on this topic?”

DiAngelo’s book is a radical statement at a time when the debate is so polarized. It seems we are forever talking about race. Or talking about why we can’t talk about race. So the problem isn’t a lack of conversation about racism but the different levels of understanding about what it is.

“We have to stop thinking about racism simply as someone who says the N-word,” she says. “This book is centered in the white western colonial context, and in that context white people hold institutional power.” This means understanding that racism is a system rather than just a slur; it is prejudice plus power. And in Britain and the US at least, it is designed to benefit and privilege whiteness by every economic and social measure. Everyone has racial bias but, as DiAngelo is determined to establish, “when you back a group’s collective bias with lingering authority and institutional control, it is transformed.”

That is why she is scathing of those who claim “reverse racism” exists; after all, people of color can show prejudice against white people. It is equally condemnable, but this form of discrimination does not come with systemic privilege and so is not racism as per the modern definition.

“Reverse is an interesting term,” she says. “Why not just say racism is racism? Reverse suggests it is going in the wrong direction. People who complain about reverse racism never seem to complain about racism otherwise. These are not racial justice advocates.”

The youngest of three daughters, DiAngelo grew up in poverty. Her mother died while she was young, an experience that she says profoundly shaped her work and world view. “In the 1960s it was shameful to have cancer, and after my mother died we didn’t talk about it. It was traumatic, even more so for the silence. I think part of that drives me to break the silence now.”

The idea that whiteness isn’t discussed is, to her, the first stumbling block. “We have a pattern of whiteness never being named or acknowledged, at the same time as we name the race of people who are not white. So we grant white people the individuality that we don’t afford people of color.” Whiteness is considered the norm for humanity, its default setting. Culture becomes something discussed only in reference to people of color. “If that is to be interrupted,” she says, “then white people must grapple with what it means to be a member of this social group.”

DiAngelo doesn’t give white people an easy ride, nor does she offer easy answers; she finds the desire to come up with quick solutions “disingenuous.”

As she puts it: “I like to push back on that urgency that white people have and the arrogance that there could be some simple, concise answer that could be handed to white people who have never thought about this before. As soon as they start asking what they’re supposed to do, there’s some sarcasm there. That’s not a genuine question, and, in my experience, they won’t do what I offer anyway.”

The idea that she could be colluding – be it unknowingly – “in someone else’s oppression” is “unbearable” to DiAngelo. It is partly why she hammers the notion that being nice to people of color is not enough. “Most people feel good intentions exempt them and so carry on not doing very much, not doing anything very different in action and practice.”

DiAngelo’s energy and focus is righteous, but it must come at a cost. Doesn’t she find it exhausting to be constantly so alert to the subject? “It’s incredibly important, so no,” she says. “It’s not draining, it’s invigorating. I get heartened, I get energy.” Isn’t this itself a marker of white privilege? I can’t think of a single non-white person who enjoys talking about race or feels energized by it. More often than not, it is awkward, uncomfortable and frustrating.

“Of course it’s uncomfortable,” she says. “And white people avoid it.” DiAngelo says her book isn’t designed to berate white people but to propel awareness and tangible action. “I want to build the stamina to handle the discomfort so we don’t retreat in the face of it, because retreating holds the status quo in place and the status quo is the reproduction of racism – and I can imagine that in the UK, as in the US, racial inequality exists.”

Very few white people, she says, will think they need to read this book. “I know my people really well, and we will do whatever we can to mark ourselves as ‘not racist.’” In her opinion, schools and the media are “the belly of the beast.”

“Schools are fantastically efficient sorting mechanisms,” she says. “They sort children into unequal places in life. We all know it, otherwise we would not care which schools our children went to.” The media, meanwhile, “continually pumps out images of white supremacy and superiority”.

In white-majority countries, isn’t that to be expected? “It’s not about majority v minority – women are the majority of the world, the poor are the majority of the world. This is about power and the concentration of that power. How does being in the majority justify inequality?”

“Racism is a white problem. It was constructed and created by white people and the ultimate responsibility lies with white people. For too long we’ve looked at it as if it were someone else’s problem, as if it was created in a vacuum. I want to push against that narrative.”

Nosheen Iqbal

Originally published on The Guardian as Academic Robin DiAngelo: ‘We have to stop thinking about racism as someone who says the N-word’

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.