Alphonso James went to prison at age 17 for a crime he did not commit.

After 32 years, he was cleared by a DNA test and returned home to Milwaukee in February 2017. Last week, he stood before about 50 people crowded into a room at the Welford Sanders Historic Lofts & Enterprise Center, 2821 N. Vel R. Phillips Avenue, and discussed his experience.

“I knew truth was on my side, but the things that we were enduring in prison were enough to suffocate a human being into nothing,” he said.

James, in a navy blue cardigan and steel-framed glasses, choked up as he described the depression he experienced in prison and how he was placed in solitary confinement for refusing medication. Early on in his sentence, James said he spent five years straight in solitary confinement. According to the United Nations, solitary confinement in excess of 15 days is considered torture.

While incarcerated, James taught himself how to read, earned a culinary degree and started programs to support his peers inside. He is now a cook at a local hotel.

James spoke at a listening session hosted by Ex-Incarcerated People Organizing (EXPO) and prompted by Angela Lang, executive director of Black Leaders Organizing for Community (BLOC), who was recently appointed to Governor Tony Evers’ Public Safety and Criminal Justice Reform Policy Advisory Council. According to a statement from Evers, the council is tasked with assisting the governor’s administration in exploring reforms of the state’s criminal justice system. The purpose of the session was to provide an opportunity for people with direct experience in the criminal justice system to tell their stories.

Of the 30 representatives selected to serve on the council, only one person had been incarcerated, according to Peggy West, lead legislative organizer for EXPO.

“When you’re talking about reform and correcting things that are wrong, it’s important to have attorneys and people like that, but it’s more important to have people who actually have lived experiences,” West said.

Lang invited West to organize the listening session. “I just want to make sure that people’s individual stories don’t get lost,” Lang said.

In addition to James, about 15 other formerly incarcerated people shared stories, concerns and suggestions with Lang and Edgar Lin, a former public defender who is also on the governor’s advisory council.

Brian Jackson reported that prison staff did not follow up on complaints, which were often considered invalid due to rigid time constraints. He said he had a brain aneurysm while incarcerated that was neglected, and he saw a man being tased until his shirt caught on fire. However, he never saw a complaint successfully filed against a staff member.

Responding to a question from Lang, Jackson said he estimates that 85 percent of people in prison experience some level of abuse, including verbal abuse.

Aaron Hicks is required to wear a GPS monitoring device for the rest of his life. He said that the GPS ankle bracelet interferes with his daily life and instills a chronic sense of fear. Hicks noted that the device was not a part of his original sentence, but was mandated by his parole officer in light of a 2006 state statute. He reported he has to pay $240 a month for the device, indefinitely. West said that as of January 2018, Wisconsin was monitoring 1,258 people on GPS devices.

Carl Fields criticized crimeless revocation, which occurs when a formerly incarcerated person is brought back to detention for violating a rule of probation or parole — or simply being suspected of a violation. Fields said that when this happens, any stability the person has acquired after leaving prison, such as housing or employment, can be lost.

Alan Schultz said he struggled with substance abuse while incarcerated and that more supports are needed for people with drug dependencies and other mental health issues.

“We are locking up people because they suffer from a drug problem,” echoed Ouida Lock. She would like to see formerly incarcerated people hired to support individuals as they transition from prison back into the community. This concept of “peer support” was raised by several people throughout the evening. Multiple attendees also requested that the governor reinvigorate the pardons board. Gov. Scott Walker did not grant any pardons during his administration.

Lang asked people to raise their hand if they experienced difficulty finding housing or employment after leaving prison. Every hand in the room went up.

“I knew things were bad, but being able to put faces to the stories was even worse,” Lang said.

Evers and Lt. Governor Mandela Barnes were sworn into office on Jan. 7. Throughout their campaign, they touted their desire for criminal justice reform and called attention to the racial disparities in Wisconsin’s system. According to data from the United States Department of Justice analyzed by the Sentencing Project, Wisconsin incarcerates African-American people at a rate of 10 times higher than their white counterparts.

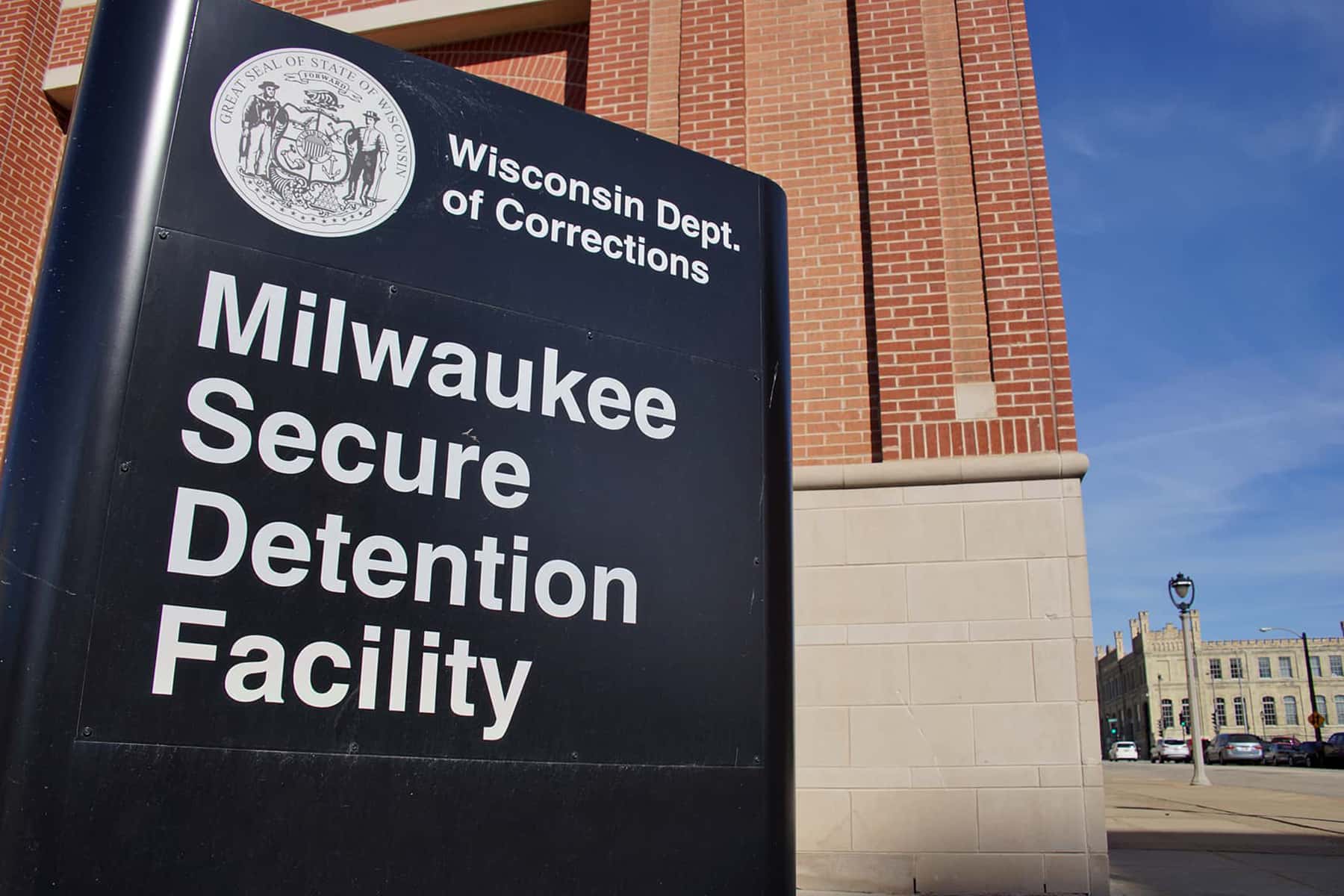

Despite a national trend to decrease prison populations, at the end of 2017, Wisconsin was still incarcerating nearly as many people as it was in 2007, when the state prison population reached an all-time high, according to counts from the state Department of Corrections.

“It is so, so important that you be attentive to the voices of these men and these women that are in here, because these are the voices that are echoing the pain that the brothers and sisters who are behind bars are experiencing every day,” James said.

Allison Dikanovic

Lee Matz and Allison Dikanovic

Originally published on the Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service as Formerly incarcerated organizers hope new state leadership brings criminal justice reform