By Mark Canada, Executive Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs, Indiana University

and Christina Downey, Professor of Psychology, Indiana University

Each new year, people vow to put an end to self-destructive habits like smoking, overeating or overspending.

And how many times have we learned of someone – a celebrity, a friend or a loved one – who committed some self-destructive act that seemed to defy explanation? Think of the criminal who leaves a trail of evidence, perhaps with the hope of getting caught, or the politician who wins an election, only to start sexting someone likely to expose him.

Why do they do it?

Edgar Allan Poe, one of America’s greatest – and most self-destructive – writers, had some thoughts on the subject. He even had a name for the phenomenon: “perverseness.” Psychologists would later take the baton from Poe and attempt to decipher this enigma of the human psyche.

Irresistible depravity

In one of his lesser-known works, “The Imp of the Perverse,” Poe argues that knowing something is wrong can be “the one unconquerable force” that makes us do it.

It seems that the source of this psychological insight was Poe’s own life experience. Orphaned before he was three years old, he had few advantages. But despite his considerable literary talents, he consistently managed to make his lot even worse.

He frequently alienated editors and other writers, even accusing poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow of plagiarism in what has come to be known as the “Longfellow war.” During important moments, he seemed to implode: On a trip to Washington, D.C. to secure support for a proposed magazine and perhaps a government job, he apparently drank too much and made a fool of himself.

After nearly two decades of scraping out a living as an editor and earning little income from his poetry and fiction, Poe finally achieved a breakthrough with “The Raven,” which became an international sensation after its publication in 1845.

But when given the opportunity to give a reading in Boston and capitalize on this newfound fame, Poe did not read a new poem, as requested. Instead, he reprised a poem from his youth: the long-winded, esoteric and dreadfully boring “Al Aaraaf,” renamed “The Messenger Star.”

As one newspaper reported, “it was not appreciated by the audience,” evidenced by “their uneasiness and continual exits in numbers at a time.” Poe’s literary career stalled for the remaining four years of his short life.

Freud’s ‘death drive’

While “perverseness” wrecked Poe’s life and career, it nonetheless inspired his literature. It figures prominently in “The Black Cat,” in which the narrator executes his beloved cat, explaining, “I… hung it with the tears streaming from my eyes, and with the bitterest remorse at my heart… hung it because I knew that in so doing I was committing a sin – a deadly sin that would so jeopardize my immortal soul as to place it – if such a thing were possible – even beyond the reach of the infinite mercy of the Most Merciful and Most Terrible God.”

Why would a character knowingly commit “a deadly sin”? Why would someone destroy something that he loved? Was Poe onto something? Did he possess a penetrating insight into the counterintuitive nature of human psychology?

A half-century after Poe’s death, Sigmund Freud wrote of a universal and innate “death drive” in humans, which he called “Thanatos” and first introduced in his landmark 1919 essay “Beyond the Pleasure Principle.”

Many believe Thanatos refers to unconscious psychological urges toward self-destruction, manifested in the kinds of inexplicable behavior shown by Poe and – in extreme cases – in suicidal thinking.

In the early 1930s, physicist Albert Einstein wrote to Freud to ask his thoughts on how further war might be prevented. In his response, Freud wrote that Thanatos “is at work in every living creature and is striving to bring it to ruin and to reduce life to its original condition of inanimate matter” and referred to it as a “death instinct.”

To Freud, Thanatos was an innate biological process with significant mental and emotional consequences – a response to, and a way to relieve, unconscious psychological pressure.

Toward a modern understanding

In the 1950s, the psychology field underwent the “cognitive revolution,” in which researchers started exploring, in experimental settings, how the mind operates, from decision-making to conceptualization to deductive reasoning.

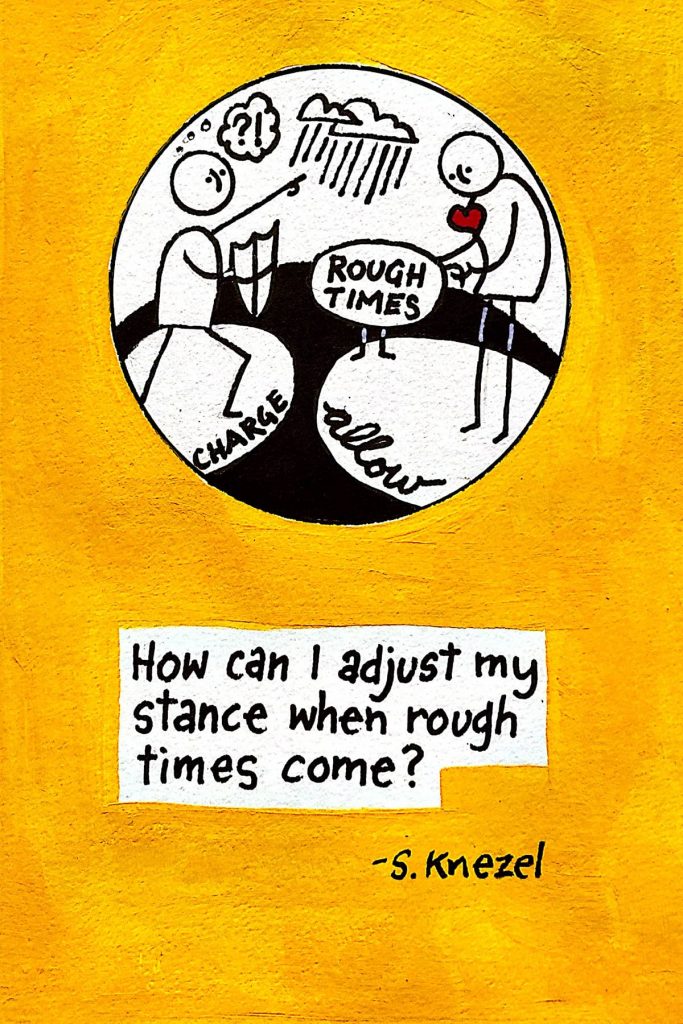

Self-defeating behavior came to be considered less a cathartic response to unconscious drives and more the unintended result of deliberate calculus.

In 1988, psychologists Roy Baumeister and Steven Scher identified three main types of self-defeating behavior: primary self-destruction, or behavior designed to harm the self; counterproductive behavior, which has good intentions but ends up being accidentally ineffective and self-destructive; and trade-off behavior, which is known to carry risk to the self but is judged to carry potential benefits that outweigh those risks.

Think of drunk driving. If people knowingly consume too much alcohol and get behind the wheel with the intent to get arrested, that is primary self-destruction. If people drive drunk because they believe they are less intoxicated than a friend, and – to their surprise – get arrested, that is counterproductive. And if people know they are too drunk to drive, but they drive anyway because the alternatives seem too burdensome, that is a trade-off.

Baumeister and Scher’s review concluded that primary self-destruction has actually rarely been demonstrated in scientific studies.

Rather, the self-defeating behavior observed in such research is better categorized, in most cases, as trade-off behavior or counterproductive behavior. Freud’s “death drive” would actually correspond most closely to counterproductive behavior: The “urge” toward destruction isn’t consciously experienced.

Finally, as psychologist Todd Heatherton has shown, the modern neuroscientific literature on self-destructive behavior most frequently focuses on the functioning of the prefrontal cortex, which is associated with planning, problem solving, self-regulation and judgment.

When this part of the brain is underdeveloped or damaged, it can result in behavior that appears irrational and self-defeating. There are more subtle differences in the development of this part of the brain: Some people simply find it easier than others to engage consistently in positive goal-directed behavior.

Poe certainly didn’t understand self-destructive behavior the way we do today.

But he seems to have recognized something perverse in his own nature. Before his untimely death in 1849, he reportedly chose an enemy, the editor Rufus Griswold, as his literary executor.

True to form, Griswold wrote a damning obituary and “Memoir,” in which he alludes to madness, blackmail and more, helping to formulate an image of Poe that has tainted his reputation to this day.

Then again, maybe that’s exactly what Poe – driven by his own personal imp – wanted.

Originally published on The Conversation as What’s behind our appetite for self-destruction?

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.