Most Americans know some version of “The Thanksgiving Story.” It is a tale that is invariably set in New England and involves pilgrims, Native Indians, and a harvest feast.

As schoolchildren, we are taught about the colonists on the Mayflower and their hard first winter. We learn about the selfless assistance the Pilgrims received from their new Indian neighbors who taught them how to plant native crops so they would not starve to death. When those crops bore fruit, the magnanimous Pilgrims invited local Indians to join them in a meal of thanks.

As we get older, we learn a slightly darker version of this story, one that acknowledges tragedy more than togetherness. We recognize that this national origins story glosses over the reality of genocide, disease and war.

Whatever the interpretation, the story of Thanksgiving has always been set in the seventeenth century, in colonial New England, in the earliest days of the English presence in North America. Few ever stop to think why we celebrate this moment. When you think about it, it does not make a lot of sense. We have a national holiday to celebrate an obscure dinner party that took place almost four hundred years ago. Why? How did this come to be?

The answer to these questions has less to do with colonial history than it does with the nineteenth century and the decades leading to the Civil War. In the decades that preceded the Civil War, Americans found themselves in an intense cultural battle over the nation’s history. As sectional tensions evolved in the 1830s, 1840s and metastasized in the 1850s, North and South developed increasingly divergent “origins stories” over America’s genesis. Sectional politics shaped sectional interpretations of history just as debates over free labor and slavery polarized national discourse. Beginning roughly in the 1830s, Americans launched themselves into an historical turf war, one that reflected the contemporary political tensions emerging between North and South.

Northern scholars, for example, celebrated the New England Puritans as the forefathers of American democracy. Scholars from prestigious northern universities like Harvard and Yale studied the founding fathers of the New England colonies in great detail. They argued that it was the Puritans who first set down the basic principles of government and organized the social contract. It was from the North, they claimed, that the origins of our great American democracy sprung forth.

Southerners, of course, argued a very different story. Southern scholars explained that America was founded in the South. They claimed that America began with the Jamestown colony in Virginia where, after all, the English established their first, successful North American colony in 1607 — nearly a decade before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock.

While northerners invented a story about Puritans in which the Pilgrims represented the seedbed of American democracy, southerners championed their own origins story: a kind of romance myth about a young Indian girl named Pocahontas who they claimed to have “saved” John Smith and embraced all things English. It was at Jamestown that the English first laid claim to their American destiny. It was not the Puritans up in Yankee New England who founded this nation, but rather Pocahontas of Virginia who was the mother of us all.

The roiling political anxieties of the 1840s and 1850s breathed fire into these competing historical narratives. Northerners and southerners dug their heels into deeply mythologized stories about the national past. The stakes were extremely high: who could lay claim to America’s destiny, the North or the South? Could we trace America’s roots to the landing at Plymouth Rock? Or did the saving of John Smith in Jamestown represent the “true” story of America’s founding? Southerners were not about to concede that the nation began in Yankee New England, a place they increasingly associated with the grind of factory labor and the heartless greed of industry.

Northerners would never agree to an American past forged in the slave South, where they saw the cruel exploitation of African Americans as antithetical to American liberty. As sectional politics grew increasingly fierce, ideas about the past shaped the present. Northern states began to adopt “days of thanks” to celebrate the contributions of their Puritan forbearers. After the outbreak of Civil War, a Virginia cavalry troop dubbed themselves the “Guard of the Daughters of Powhatan.” Their flag depicted an image of Pocahontas, linking the cause of the Confederacy to a defense of southern colonial history.

For all of the contentiousness and division, however, both northern and southern interpretations of American history shared an important common theme — one that makes these debates particularly relevant for us to understand today. Both versions of these historical “origins stories” contained a shared, assumed and intense commitment to the fiction of an Anglo-American past.

For all their public assertions of difference, both North and South articulated visions of America’s founding that celebrated English origins and implied that the nation began as — and would become — a white, Anglo-Saxon empire. Whether it was the Puritans who invited the Indians to dinner, or Pocahontas who rejected her “savage” ways to marry an Englishman, sectional debates over history allowed both northerners and southerners alike to engage in a narrative celebration of America’s manifest whiteness.

Much like the historical debates themselves, the impulse to white-wash the American past emerged out of contemporary circumstances. Part of the reason that northerners began to cling to the Puritan story was because it allowed them to celebrate a white, racial past during a time when the North felt itself under siege by foreign immigrants. From the colonial period onward, the North had always been ethnically pluralistic, but during the nineteenth century, people from all over the world — and particularly from Germany and Ireland — descended upon northern cities to work in burgeoning factories and industry. This flood of immigrants caused a nativist panic among those who treasured their sense of Anglo-American superiority.

A story of Puritan origins institutionalized a sense of white racial destiny for northerners who felt their significance increasingly marginalized by foreign immigration. In the South, the historical fetish for the “Indian princess” Pocahontas helped mask an ongoing genocidal Indian removal policy. As national leaders rounded up southeastern Indians and marched them out of the South in a Trail of Tears, southerners found historic justification of their ethnic cleansing policies in the conversion of a young Indian girl to English culture.

The historical stories that Americans told about themselves in the early nineteenth century reflected our nation’s long and tragic efforts to supress the reality of diversity. Today, we are stuck with a Thanksgiving tale about the New England Pilgrims because the North won the war and claimed the right to tell the story.

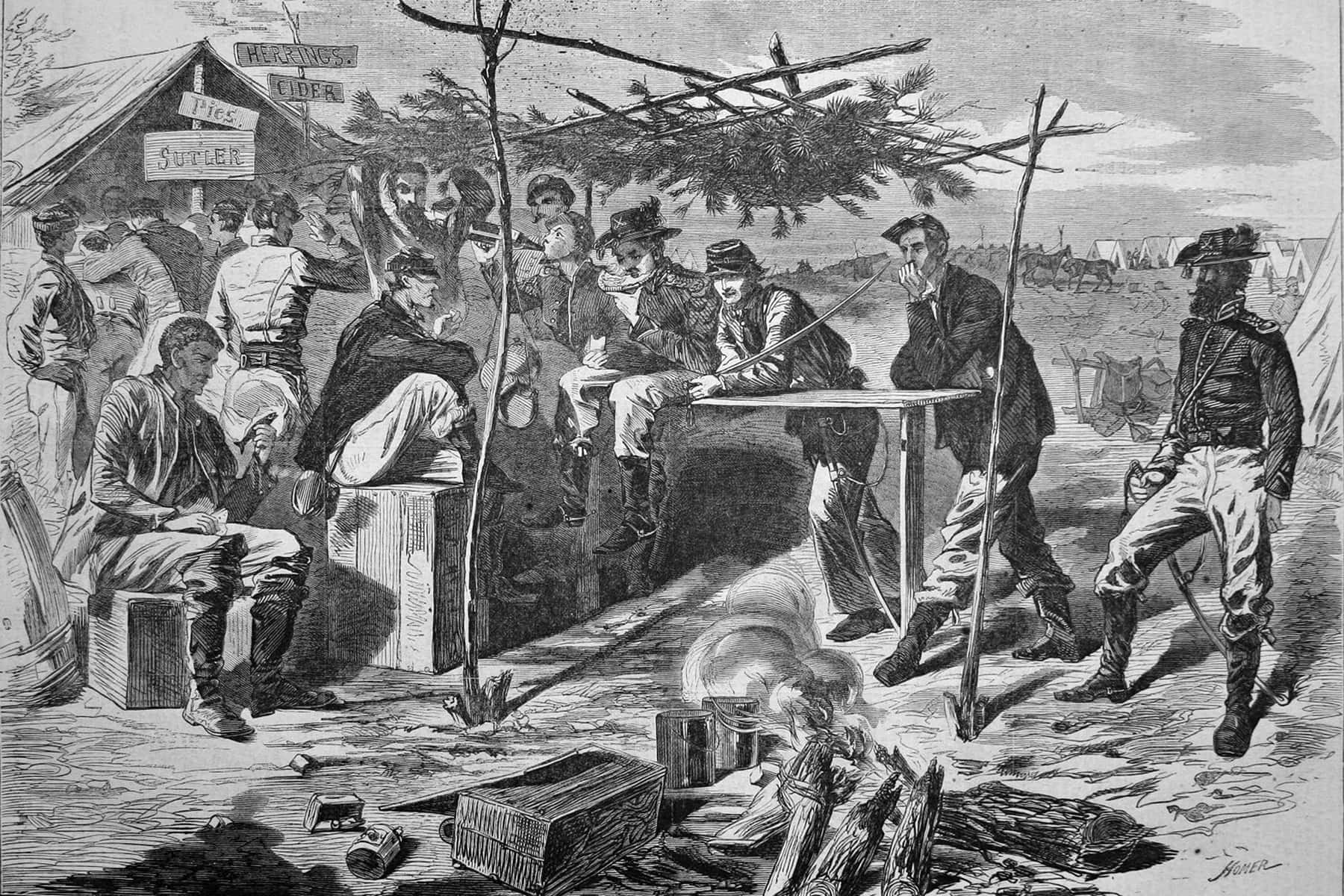

But there is an alternative version of the Thanksgiving story, one that might provide better perspective on our currently divided nation. In 1863, in the bowels of Civil War, Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation to establish the first national day of Thanksgiving. He called on his “fellow-citizens in every part of the United States” to “set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a Day of Thanksgiving.” Lincoln’s proclamation made no mention of Pilgrims or Indians.

He did not mention North or South nor did he speak of founding fathers or national origins. Rather, Lincoln called attention to our desperate need for collective healing. Lincoln proclaimed a national Thanksgiving Day to “commend to his tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife” that the nation faced. He called for a day in which we might sit down and work to “heal the wounds of the nation.”

Today, perhaps as poignantly as in 1863, such a spirit of Thanksgiving is desperately needed.