Growing up in the Pacific Northwest, I hiked with my family every late summer and early fall to scan the forest floors of places like Port Townsend and North Bend for matsutake and warabi, “monkey chairs” and chanterelles, our feet sometimes cushioned by blankets of drying pine needles, other times by pungent quilts of rain-soaked mosses.

We would lightly cane the ground with our forked walking sticks, pushing up a little mound of dirt that we anticipated would reveal a cache of Japanese pine mushrooms or brushing back a berry bush that just might reveal a patch of bracken fern, bracket fungus jutting from a tree or golden chanterelles stretching toward the limited sunlight. We learned which ones were edible, and which ones were so poisonous that they were fatal if ingested. At home, my Japanese grandmother would marinate the matsutake mushrooms in soy sauce, boil the ferns, make a digestive of the bracket fungus and mix the chanterelles with sushi rice, transforming the earthy ingredients with tradition and care.

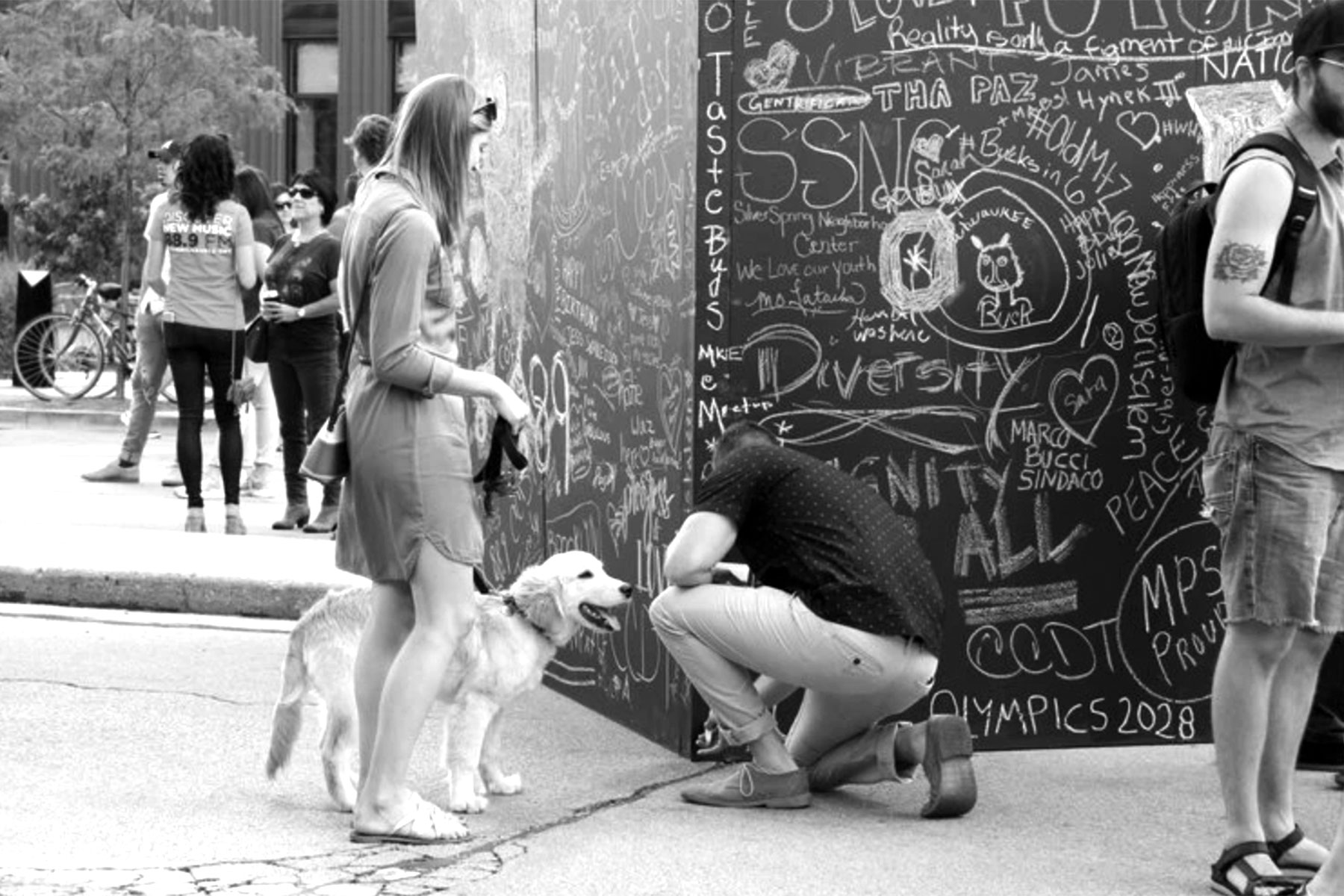

In Milwaukee, during the month of May, hundreds of people will be enacting their own version of mushroom hunting as they explore the city on foot, bike and kayak, foraging for signs of life and development, void and transformation, our history and our future.

Milwaukeeans will be joined by citizens from at least three dozen countries, in over 200 cities, as they celebrate with Jane’s Walk, a worldwide movement started in 2007 to celebrate the legacy of urbanist and activist Jane Jacobs by observing, reflecting, questioning and collectively reimagining the places in which we live, work and play. The local organization aptly named Jane’s Walk MKE believes in building a “walkable, talkable city,” planned for and by citizens, envisioning a Milwaukee that has, to borrow from Jacobs’ 1961 Death & Life of Great American Cities, “the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, [it is] created by everybody.”

WALKING WITH JANE JACOBS

To do so, while cities typically celebrate Jane’s Walks during the first weekend of May to coincide with Jacobs’ May 4th birthday, Jane’s Walk MKE has an entire month of exploration planned. From their perspective, a “walk” is any organized activity of “self-propelled human bodies” (an equitable term for which I thank Emily Talen, Professor of Urbanism at the University of Chicago, at her recent UWM lecture called Walkable + Diverse Cities: What Could Go Wrong?).

This means that Jane’s Walk MKE can encompass and encourage not only ambulatory explorations but running, bicycling, paddling, mass transit and wheelchair-accessible ones.

For the third year in a row, Jane’s Walk MKE is offering free, citizen-led neighborhood explorations, with already twice the number of walks as were offered in 2017. As of this writing, planned walks will celebrate economic and ecological development along Wisconsin Avenue and in Lindsay Heights; others will assess the walkability and safety of Kinnickinnic Avenue, South Water Street and the Locust Street Bridge. Some will explore beautiful parks like Three Bridges and Hawthorne Glen; others will paddle Lincoln Creek and the Milwaukee River and investigate Milwaukee’s clean water infrastructure (by bike). Walks will explore the past of Walker’s Point, Jones Island and the Beer Line, as well as look forward to developments like the riverwalk extension in the Menomonee Valley.

Walks will happen in over twelve ZIP Codes, but even more are in the works, including a leisurely downtown streets and parks stroll, resident-led tours of Sherman Park’s Center Peace neighborhood and Williamsburg Heights, an architectural tour of Martin Drive, a celebration of business development along Dr. Martin Luther King Drive and even a dog-walking stroll in Lake Park, a Jane’s Jog and a walk integrating creative writing and fashion. Cesar Chavez Drive and Westlawn Gardens are also on the docket. Finally, Jamin Creed Rowan, author of The Sociable City: An American Intellectual Tradition, will lead a walk through the East Side, culminating in a discussion at Boswell Books about his book on the intersections between the physical and social urban landscapes of our country. This year’s walk series will surely accomplish more of Jane’s Walk MKE’s goal to expand the walk map beyond routes close to downtown and the lake, where most walks in the past have been concentrated.

But wait, you say: didn’t this column start with mushrooms? It did, indeed. Soon, it will become clear that both my family and Jane Jacobs were searching for the same things: a nourishing but often hidden or ignored vitality that can be harvested to transform a body, a city. But don’t worry: like most Jane’s Walks, I will come full circle. But first, listen to how Jacobs used another metaphor, what she called “the sidewalk ballet,” to describe the vitality in her New York City neighborhood. Surely, “sidewalk ballet” is more elegant than saying “sidewalk mushrooms”:

…Wherever the old city is working successfully is a marvelous order for maintaining the safety of the streets and the freedom of the city. It is a complex order. Its essence is intricacy of sidewalk use, bringing with it a constant succession of eyes. This order is all composed of movement and change, and although it is life, not art, we may fancifully call it the art form of the city and liken it to dance – not to a simple-minded precision dance with everyone kicking up at the same time, twirling in unison and bowing off en masse, but to an intricate ballet in which the individual dancers and ensembles all have distinctive parts which miraculously reinforce each other and compose an orderly whole. The ballet of the good city sidewalk never repeats itself from place to place, and in any one place is always replete with improvisations.

Here, she champions the locksmith and the cigar seller, the tailor and the launder, the pizzeria and the delicatessen – and the myriad interactions that occur in the ecosystem of a well-planned street between sunup to sundown. She laments those who don’t know such “animated city streets,” those who, she fears, “will always have it a little wrong in their heads – like the old prints of rhinoceroses [drawn based on] travelers’ descriptions of rhinoceroses.” One needs to experience the sidewalk ballet to truly understand its worth and necessity. And one can only do that at the street level, on a human scale, not peering down from a high rise or whizzing by in a car, not confined to poverty or a poor transportation infrastructure. Too many, we know, don’t have these opportunities; others still, don’t know how to.

WALKERS AS CITIZEN EXPERTS

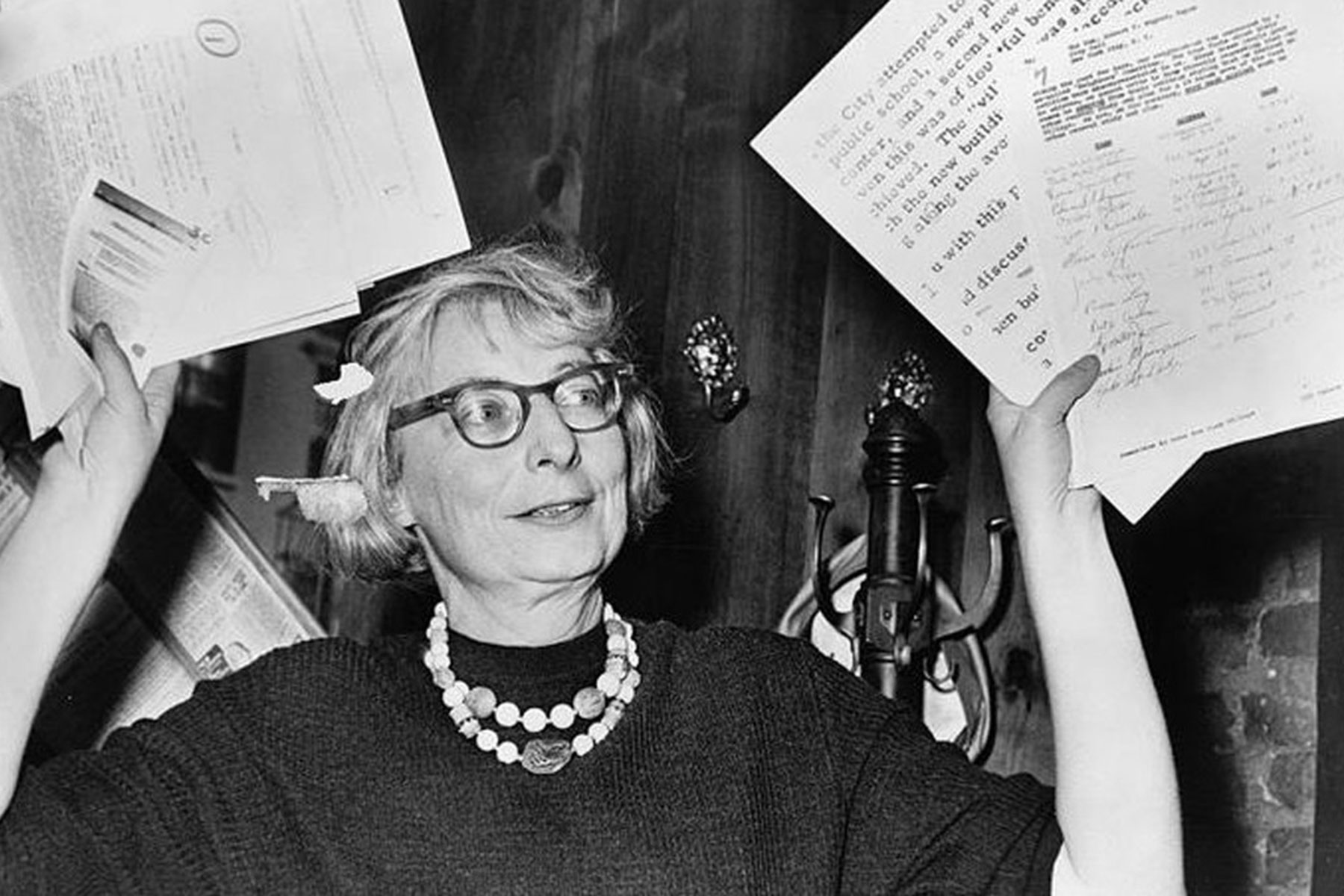

The eponymous Jane Jacobs was American-Canadian, born in 1916 in the coal mining town of Scranton, Pennsylvania, settled with her husband in New York City and died in Toronto, where she and her family moved in 1968 in response to the Vietnam War, in 2006. One thing that made Jacobs a hero in some eyes and anathema in others is that when she burst onto the scene in the 1950s, she was one, a woman, and two, a woman with no college degree and no urban planning training. Her speeches and writings relied on her personal observations about what makes a city work – or not work. With the release of Death & Life, terms like “eyes on the street,” “social capital” and “sidewalk ballet” entered urban planning parlance whether people liked it or not. She argued that any citizen, like herself, could observe and study their own city, inquire about it, critique it and act to change those elements that needed changing. Because citizens are at the heart of cities – what she believed to be integrated, synergistic ecosystems – she believed that citizens “can be the ultimate expert[s]… what is needed is an observant eye, curiosity about people, and a willingness to walk.”

Jacobs’ own observant eyes focused on what worked and what didn’t work in the New York City of the 1950s and 1960s. Two things that didn’t work, she argued, were high-rise public housing projects, which required “slum clearances” that often displaced hundreds of residents, and freeway expansions that threatened to tear through neighborhoods like SoHo, Little Italy, and her own Greenwich Village. Milwaukee knows too well the aftermath of the freeway system, resident displacement and, arguably, gentrification. She took on grassroots campaigns against the New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses–one of the biggest proponents of freeway construction over public transit and himself untrained in urban planning, architecture or engineering – by advocating for low-rise, mixed-income housing and dense and diverse neighborhoods (like Greenwich Village) that integrated different building types and uses, residences and businesses and a diversity of populations. For Jacobs, a lively city had shorter blocks, juxtaposed the old and new and accommodated both vehicles and pedestrians safely, with the emphasis on pedestrians, Most of all, she modeled and supported bottom-up community planning.

WALKABLE STREETS FOR ALL?

Of course, Jacobs’ ideas and the results of them are not without critique. Her urban planning concepts, some argue, are not universal. Some will argue they ignore modern transportation needs or overpopulation. Others point out how the “animated streets” of high density and diversity, like those she knew in Greenwich Village, have, through a long process of gentrification (which she probably could not have expected) that has resulted in some of the highest property values in the world. According to a recent Realtor.com study, the median residential sales in Greenwich Village have actually dropped 40% to a whopping $1,975,000. And residences in Little Italy, another neighborhood Jacobs helped saved from the freeway, has seen a 147.1% increase in value, with a median sale price of over $3.2 million.

Social and health inequities, too, have long diminished or destroyed any sidewalk ballet that existed in certain neighborhoods (like Milwaukee’s Bronzeville), particularly those in disinvested ones. Dr. Robert A. Bullard, founder of the Environmental Justice movement, once argued: “Tell me your ZIP Code and I can tell you how healthy you are. That should not be… All communities should have a right to a safe, sustainable, healthy, just, walkable community.” Addressing the sad reality, Jay Walljasper, in “Walking is a Fundamental Human Right,” writes, “Yet many people across the country now think twice before traveling on foot due to dangerous traffic, street crime, racial profiling, or a lack of stores and public places within walking distance. Forty percent of all Americans say their neighborhood is not very walkable, according to a survey commissioned by Kaiser Permanente, one of America’s largest healthcare providers. A full quarter of Americans report they are deterred from walking by speeding traffic or lack of sidewalks, and 13 percent say crime keeps them indoors.”

Milwaukee, of course, has its own systemic issues with neighborhood health and housing inequity. Freeways, redlining and economic depression helped segregate the city along racial and class lines, cementing pockets of wealth and even bigger sinkholes of poverty. All the more reason, then, to address the lack of visible and viable sidewalk ballet throughout the city. Jacobs hope was that “vital cities have marvelous innate abilities for understanding, communicating, contriving, and inventing what is required to combat their difficulties… Lively, diverse, intense cities contain the seeds of their own regeneration, with energy enough to carry over for problems and needs outside themselves.”

Demonstrating that Milwaukee is indeed a “vital city,” recent efforts worth highlighting include the designation of the revitalized Dr. Martin Luther King Drive as the first official “Main Street” in Milwaukee, the HomeWorks initiative in Bronzeville that will create mixed-use residences and artist studios out of old buildings, the award-winning Westlawn Gardens public housing community and the creation of neighborhood-improvement organizations like the Clarke Square Neighborhood Initiative and Harbor District Milwaukee. Jane’s Walk MKE will only help bring to light more of the successes and challenges that face the city’s almost 200 neighborhoods.

Much work still needs to be done to expand the reach of Jane Jacobs’ message to all corners of the city, to empower ordinary citizens to design and demand the kind of walkable city they want. This is going to need some serious psychological and political paradigm shifts, ones in which we as citizens realize our individual and collective power to imagine and create, destroy and rebuild. No matter what ZIP Code we live in, no matter our history and despite those in elected office, the streets belong to us. Our feet (and any other self-propelled human action) belong to us. And so, this brings me back, finally, to mushroom hunting.

WALKING INTENTLY TOGETHER

One accomplished mushroom hunter was experimental composer John Cage, who also co-founded the New York Mycological Society. Foraging’s combination of walking and paying attention to one’s environment fascinates me, especially now in the context of Jane’s Walks. In his “Mushroom “Book,” Cage likens “hunting [to] starting from zero, not looking for.” While many of the walks planned for May will necessarily have an explicit focus and participants will know what they are looking for – buildings, historical references, ecological decline or success, new people in a new part of town – I want to leave room for “starting from zero,” for the psychological wanderings of the Surrealists that I wrote about in my previous column, the ones that were open to finding the marvelous in the banal. Like the Situationists, I want to leave room for subverting the established and utilitarian way we move (and are moved) through the city.

Neither of these walks I’m planning will actually be “planned,” per se. They will have a starting point, of course, but may not have a clear ending point. Instead, they will draw upon, as needed, a repertoire of possible walking habits and peculiar exercises influenced by the Surrealists and Situationists. They will question why we walk and how we walk, how we are forced to walk and how we choose to walk, who gets to walk and who doesn’t, what it means to be a self-propelled human body with a human right to travel freely.

Finally, Cage, the composer and mycologist, was one of the main influences behind what was called the Fluxus movement, which insisted on real experience as a way to learn about the world, real experience as art, using the entire active body to interpret the everyday. For a Fluxus artist, the very childhood act of poking in the moss for mushrooms might be considered “art.” The boiling of a bracket fungus. A walk down Brady Street or in a crosswalk on Capitol Drive. A detour into an alley to contemplate a mural or the picking up of litter in a park.

Therefore, I will leave room in one walk for Fluxus “compositions,” which were written instructions to participants, who would then interpret them for an audience. These compositions will have us focus on the dignity of our Milwaukee bodies as we move through Milwaukee space, taking our ordinary actions, making them extraordinary and helping us to see ourselves and our place in the city anew. Without giving anything away, I will leave here with one such composition by Takehisa Kosugi called “Theater Music” (1964), which read, simply,

Keep walking intently.

Imagine the 600,000 ways Milwaukee citizens would interpret these three words. And imagine them all walking intently together, this May and beyond.

© Photo

Dominic Inouye, Kristine Hinrichs, Janeen M. Kagel, and Caitlyn Taylor