The ongoing commemoration of the 1967 open housing marches reminds us of the more recent challenges African-Americans have faced in Milwaukee, but they have encountered difficulties from Milwaukee’s earliest days. One of the lowest points occurred while the nation was engaged in a struggle that ultimately freed African-Americans from bondage.

Milwaukee’s pre-Civil War black population was never large. By 1850, 101 called Milwaukee home. Some settled there because of the city’s reputation (though not necessarily deserved) as a center of abolitionist sentiment and as an active station on the “Underground Railroad,” helping refugee slaves escape to the North. [1] Additionally, blacks moved to Milwaukee because work was readily available. A flood of Irish and German immigrants in the 1840s and 1850s transformed the fledgling community into a booming frontier city. The relatively fluid conditions enabled blacks to secure jobs as carpenters, joiners and masons, and some worked as barbers. But for the most part, economic discrimination and exploitation relegated blacks to domestic jobs or the most menial tasks. Still, several in Milwaukee owned modest amounts of property—especially west of the Milwaukee River and in the lower reaches of the Third Ward on the east side—and their children attended school with white children. [2]

Conditions, however, deteriorated in the 1850s. Racial and economic tensions between blacks and Irish increased as the latter, mostly poor, unskilled laborers, inundated the Third Ward and competed with blacks for jobs. Tension and copious amounts of liquor—the area had Milwaukee’s highest concentration of saloons—fueled physical confrontations, helping the district become known as the “Bloody Third.” [3] Antipathy overflowed into the political realm. The Irish were staunch Democrats, and during state constitutional debates in the 1840s, the party of immigrants pushed for liberal suffrage that allowed immigrants to vote but limited the privilege to white males. Attempts in the 1850s to extend the vote to blacks likewise failed, even with the rise of the Republican party. The Republicans were a conglomerate of political affiliations coalesced around opposition to the spread of slavery. However, the attitudes of most Republicans toward blacks differed little from Democrats. The state legislature even considered, but did not pass, a bill in 1858 to restrict further immigration of free blacks into Wisconsin. [4]

The federal government also undermined African-Americans’ peace and security when Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. This law placed stringent fines upon officials who failed to arrest runaway slaves and citizens who helped fugitive slaves escape. In addition, suspected slaves could not request a trial by jury or even testify on their own behalf. Milwaukee’s black community was alarmed. At a hastily called gathering, former slave Joseph Barquet urged others to “point our brethren to the north star. The eagle no longer protects him under the shadow of her wings. Let him go and throw himself under the tender clutches of the British lion [in Canada].” [5] The March 1854 capture of fugitive slave Joshua Glover in nearby Racine made the threat of slave catchers uncomfortably real. To avoid trouble from outraged Racine residents, the U.S. Marshal brought Glover to Milwaukee, hoping he could be transported out of the city quietly. But word quickly spread, and a mob attacked the county jail and freed Glover. He was spirited away to Waukesha and eventually to Canada. Milwaukee’s black community viewed the episode as a warning that any of them could be snatched away by slave catchers at any time. Some panicked and fled to safety in Canada. But the community endured. [6]

James P. Shelton and George Marshall Clark were among the few African-Americans to make Milwaukee their new home in the 1850s. Born in Virginia in 1832, Shelton settled in Milwaukee around 1857 and worked as a carpenter and waiter in Francis Anderson’s confectionary shop. Clark was born in Pennsylvania in 1838, the son of George H. Clark. The elder Clark relocated to Milwaukee in 1847 and established himself as a successful barber and respected leader of the black community. George followed his father to Milwaukee around 1858 and likewise tried to make a go of it as a barber, but according to an antagonistic newspaper, he was “an ugly, dissipated and worthless fellow.” At the very least, Shelton and Clark were acquaintances, and more than likely, they became friends. According to the 1860 census, both lived at the same residence at Third Street and Cedar (now Kilbourn Avenue). [7]

On Friday evening, September 6, 1861, Shelton and Clark were walking along Milwaukee Street just south of the corner at Michigan Street when they came upon Darby Carney and his friend John Brady, a farmer from Muskego. Carney operated the Emmett House, a saloon popular with the Third Ward’s Irish. He also was a noted troublemaker and fighter with a hair-trigger temper. Between 1853 and 1859 he had been arrested and/or fined five times for disorderly conduct, once for assault, once for trying to free prisoners from police custody, and once for shooting another man. [8] Words were exchanged, and in response to a comment by Carney, Shelton replied, “I know you. God damn you Carney. I can whip you or any Irishman or any white man in Milwaukee.” A fight ensued during which Shelton pulled a knife and slashed Carney across his abdomen and stabbed Brady in the shoulder. Accounts of the cause of the altercation vary. One indicates Shelton and Clark were escorting two white women, and when they passed Carney, he made a derogatory remark about white women with “d— niggers.”

Another alleges Shelton and Clark came upon two white women and made some insulting remarks to which Darby and Brady took offense; however, subsequent descriptions—including those by Brady and Carney themselves—do not mention any women involved. But it was clear both men had been drinking. As Shelton and Clark made their escape, they attacked a third individual who was lighting street lamps. The two tried to lose themselves in the crowd at Dan Rice’s circus, but police eventually found and arrested both in the early morning hours of September 7 and brought them to the county jail (located on what is now the north side of Cathedral Square). [9]

After suffering his wound, Carney staggered home. His wife called for a priest and Dr. Thomas Hatchard. When Hatchard arrived around 9:00 p.m., he found intestines protruding from Carney’s wound. Hatchard put the intestines back and sewed the wound shut, but it was clear the injury was fatal. Carney lingered all through Saturday, dying at 10:30 that evening. Before his death, he named Shelton as his attacker. As Carney lay in bed, a crowd gathered outside his house and made plans that if Carney died, they would march to the jail and remove Shelton and Clark. A fire alarm would be the signal. Policeman John McCarty was there and overheard the plan. He warned some of them not to go through with it. Nevertheless, word of Carney’s demise spread rapidly, and soon the ringing bell at Engine House No. 6 on Detroit Street (now E. St. Paul) alerted angry onlookers to act on the plan. Others reinforced the procession as it moved toward the courthouse until the crowd numbered as many as 300.

Police Chief William Beck saw the group approach the jail at 12:30 a.m.; he ordered William Kendrick, the jailor, to lock Clark and Shelton in a large room in the back and then lock the door leading to the cells. Beck went outside to confront the mob. One of the leaders, John McCormick, told the chief they had come for the two prisoners, but Beck refused to turn them over. McCormick replied, “Well, we’ll see.” Some in the crowd threatened to “go right over” Beck, and others demanded he step aside or get hurt. Beck told the gathering that the “men who hurt your friend Carney we have them arrested and propose to keep them” and that they should let the law take its course. The crowd erupted, and someone grabbed Beck, pushing him aside. A flying object struck Beck in the head and knocked him senseless. The crowd poured into the jail, and one of the mob pointed a pistol at Kendrick through the inner door, demanding he open it. He refused. Not wanting to harm a policeman, the crowd found a piece of timber and hammered in the door.

They forcibly seized keys to the cells and back door of the jail from the assistant jailers, opening it so cohorts could enter. Hearing the mob in the corridor, Shelton quickly moved into an empty cell that adjoined the back room and closed the door, leaving Clark alone. The crowd seized Clark, beat him severely, grabbed his arms and legs, and carried him into the hall. Kendrick would later testify that he saw blood spattered on the wall as well as a pool of blood where the crowd was standing. With the mob focused on Clark, Shelton escaped out the back door.

The crowd moved in fits and spurts as it dragged the unfortunate Clark down Jackson Street, debating all the while whether they had the right man. Some threatened to hang him regardless; others argued that they should take Clark to Engine House No. 6 and keep him until the next day. At least three Milwaukee residents urged the mob to be sure they had the right man before they took his life. Dr. Hatchard warned the group to be careful, pointing out that another lawless mob had crucified “our Savior.” Someone came up to Hatchard and said, “shut up you d—d preacher, or we’ll call the boys and tar and feather you.” Members of the mob made their way to a street light at Huron (now E. Clybourn) and Water streets to see if they could positively identify the captive, but his face was so bloodied and swollen, they could not. They questioned Clark, who denied he was the guilty party. He said his name was George Marshall and that he was in jail for stealing. Still unsure what to do with him, the crowd eventually took Clark to the engine house.

Once there, several men trundled Clark to an upstairs room and put him through a “trial.” Clark again claimed he was in jail for picking a man’s pocket. After about an hour, James O’Brien allegedly burst into the engine house and exclaimed Clark was indeed the right person. He was brought down from upstairs and dragged outside with a rope around his neck and through his mouth. As the crowd moved along Huron, some of Clark’s captors repeatedly kicked and punched him. One hit him on the head with a club. They took him to a pile driver at the foot of Buffalo Street between Main (now Broadway) and Water streets. The rope was tossed over a cross piece, and four men pulled Clark into the air. He raised his arms either as a plea for his life or as a last desperate attempt to remove the rope, but someone yanked his arms down. He struggled for about 20 minutes before he perished. As the crowd thinned, some suggested they let Clark hang until morning, but an onlooker said it was not “Christian like to let a man hang so long.” [10] Around 2:30 a.m., two policemen cut Clark down and took his body to the police station.

The Milwaukee News reported that “intense excitement prevails throughout the city. Thousands have already visited the gallows and deadhouse, carrying away pieces of the rope, &c.” [11] The Milwaukee Sentinel condemned the fiendish mob for torturing and murdering Clark, adding “A pleasant picture to present to the world this morning, truly!” The Sentinel—a supporter of the Republican party—added political fuel to the flames by declaring there was a “dreadful truth” underlying this “foul blot” upon the city and that was that “city authorities are impotent to protect us from a mob.” It laid blame squarely upon the weakness of Democrats Mayor James Brown and Sheriff Charles Larkin as well as the police department for giving strength to the “ruffians and lawbreakers.” Plans for the lynching were not so secret that the police knew nothing about it but “not a straw was laid in their way, except by one individual [Chief Beck], whose zeal in the preservation of order brings him always a harvest of blows or abuse.” [12]

The city’s Democratic newspaper, the Milwaukee News, vigorously defended the mayor and sheriff. It printed a letter from a reader that crystallized the editors’ stance. The letter charged that Clark’s hanging was the fruits of the treachery of “abolition fanatics” who appealed to a “higher law” when it freed Joshua Glover from the county jail in 1854. The mob that killed Clark, the writer stated, did the same. This was the result of an “irrepressible conflict” between the black and white races, making it impossible for them to live together “except in the relation of master and slave.” [13]

This prevailing attitude and Clark’s death had a chilling effect on Milwaukee’s black community, and out of fear of the mob, many decided to leave. They had reason to worry. On Sunday night, about a dozen blacks were on board the steamer Michigan waiting to depart when a crowd of 200-300 Irishmen came down to the wharf in search of Shelton. The captain had the passengers come up on deck to be inspected by the crowd. At this point, someone shouted, “Be Jasus, let us kill all the d—d nagers, and then we’ll be sure to get the right one.” Fortunately, no trouble occurred as Shelton was not among the passengers. Instead, he had fled to the farm of African-American Richard Moore, about four miles south of Waukesha. Shelton was re-captured there on September 9 and brought back to the county jail.

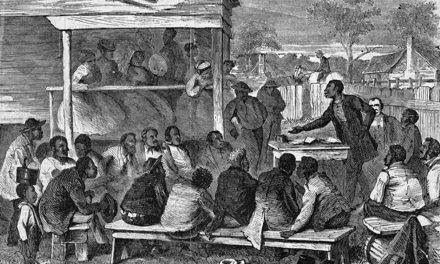

To prevent a repeat of the previous night’s riot, Sheriff Larkin requested and received militia units to guard the jail. The News reported that the soldiers’ cordoned off several blocks around the jail, and the cannons and campfires gave the appearance of a “grand camp ground.” [14]

On September 30, Shelton’s trial on 2nd-degree murder charges commenced. That same day, Milwaukee’s Board of Aldermen—no doubt wanting to whitewash the scene of the horrible crime—instructed police to remove the pile driver on Buffalo. The trial proceedings took nearly a week. Defense Attorney J.V.V. Platto called several witnesses who vouched for Shelton’s good character. Furthermore, the Sentinel commented that Platto’s shrewd cross-examinations “very materially” weakened the prospect of a conviction. On October 7, the jury found Shelton not guilty, claiming he acted in self-defense. The verdict was not well received by Carney’s friends, and Sheriff Larkin and Platto quickly smuggled Shelton out of the city to Watertown, where he boarded a train for Chicago. [15]

The episode was not over. A few days later, the coroner’s inquest issued warrants for several people involved in the riot. Police arrested six men, causing a good deal of excitement in the Third Ward. On October 29, a grand jury indicted Thomas Nichols and Dennis Delvry for murdering Clark and indicted John McCormick, James O’Brien, John Divine and Patrick McLaughlin because they “did incite, move, procure, aid, counsel, hire and command” Nichols and Delaney to commit the crime. Judge Arthur MacArthur opened the trial on November 14. District Attorney Joshua Starks tried to convince the jury that the defendants had conspired to incite a riot and commit murder. A parade of witnesses, including many Irishmen and public officials, provided conflicting accounts of the riot and the defendants’ roles. As a result, the jury notified the court on November 23 that it had failed to reach a verdict and was dismissed by the judge. The defendants demanded a new trial. Eventually, a new trial was held in late January 1862. This time, they were found not guilty. [16]

Fortunately, George Clark’s lynching was the only such occurrence in Milwaukee’s history, but the entire tragic episode was more than a mob outburst. It reflected the political, economic and social divisions tearing the nation apart on Civil War battlefields. Indeed, it was a microcosm of the violent undercurrents within America, as well as racial and ethnic tensions and the ambivalent attitudes about blacks and their place within American society. Though this “foul blot” has faded from our collective memory, many of the issues behind it have not been resolved.

Kevin Abing, PhD

1. See Jaclyn N. Schultz, “In Search of Northern Freedom: Black History in Milwaukee and Southern Ontario, 1834-1864,” Wisconsin Magazine of History (Autumn 2017), 43-47.

2. William J. Vollmar, “The Negro in a Midwest Frontier City, Milwaukee, 1835-1870,” (M.A. Thesis, Marquette University, 1968), 2-17, 22-33; William T. Green, “Negroes in Milwaukee,” in The Negro in Milwaukee: A Historical Survey (Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1968), 6-7; Leon F. Litwack, North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States, 1790-1860 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961), 153-158; R.O. Washington and John Oliver, An Historical Account of Blacks in Milwaukee (Submitted to The Milwaukee Urban Observatory, 1976), 2-3, 5-6.

3. David G. Holmes, Irish in Wisconsin (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2004), 32, 41-42; John Gurda, Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods (Milwaukee: Historic Milwaukee, Inc., 2015), 20; Kathleen Neils Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836-1860: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1976), 67, 142-143; Litwack, North of Slavery, 158-166; Shelby Callaway, “Free Blacks in Antebellum America,” African Americans in the Nineteenth Century, Dixie Ray Haggard, ed. (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2010), 19.

4. Holmes, Irish in Wisconsin, 41-42; V. Jacque Voegeli, Free but Not Equal: The Midwest and the Negro During the Civil War (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967), 2-9; Richard N. Current, The History of Wisconsin. Vol. II: The Civil War Era, 1848-1873 (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1976), 145-146, 260-268; Schultz, “In Search of Northern Freedom,” 47; Vollmar, “The Negro in a Midwest Frontier City,” 46-51.

5. Cited in Ruby West Jackson and Walter T. McDonald, Finding Freedom: The Untold Story of Joshua Glover, Runaway Slave (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2007), 24.

6. For in depth accounts of the Glover rescue and its aftermath, see Jackson and McDonald, Finding Freedom and H. Robert Baker, The Rescue of Joshua Glover: A Fugitive Slave, the Constitution, and the Coming of the Civil War (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2006). See also, Chester V. Salomon, “Negro Recognition in Early Milwaukee,” in Historical Messenger of the Milwaukee County Historical Society (September 1965), 79-81; Washington and Oliver, An Historical Account of Blacks in Milwaukee, 6-7.

7. 1860 Federal Census, City of Milwaukee, 2nd Ward, p. 6; Milwaukee city directories, 1857-1861; Vollmar, “The Negro in a Midwest Frontier City,” 17, 56-57; Milwaukee News, September 10, 1861.

8. State of Wisconsin vs. Darby Carney, Criminal Court Case #48, September 1856, Mss-2124, MCHS; Vollmar, “The Negro in a Midwest Frontier City,” 65; see also “Carney, Darby” entries, Milwaukee Sentinel index, Milwaukee Public Library.

9. Milwaukee News, September 8 and November 15, 1861; Milwaukee Sentinel, September 7, September 9-10, 1861.

10. The description of the lynching is derived from Vollmar, “The Negro in a Midwest Frontier City,” 65-69; Frank Flower, ed., The History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Chicago: The Western Historical Company, 1881), 299-305; Milwaukee Sentinel and Milwaukee News, and records from the James P. Shelton Collection, Mss-2695, MCHS.

11. Milwaukee News, September 10, 1861.

12. Milwaukee Sentinel, September 10, 1861.

13. Milwaukee News, September 13, 1861.

14. Milwaukee News, September 8, September 10 and September 11, 1861; William T. Green, “Negroes in Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 16, 1895; Richard N. Current, The History of Wisconsin. Vol. II: The Civil War Era, 1848-1873 (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1976), 389-390

15. “The Sheldon Murder Trial,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 9, 1861; Criminal Court Docket, Vol. C, p. 505-506, MCHS; Milwaukee. Board of Alderman. Minutes, Mss-0737, MCHS; State of Wisconsin vs James P. Shelton: Minutes of the Judge, James P. Shelton Collection, Mss-2695, MCHS; Vollmar, “The Negro in a Midwest Frontier City,” 69-70; Frank Flower, ed., History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Chicago: The Western Historical Company, 1881), 304.

16. Criminal Court Docket, Vol. C, p. 510-511, 516-518, MCHS; Milwaukee Sentinel, November 16, 18-22 and 25, 1861; Milwaukee News, October 12 and November 15-16, 18-19 and 25, 1861; State of Wisconsin against John McCormick, Dennis Delury, James O’Brien, Patrick McLaughlin and John Devine, in James P. Shelton Collection, Mss-2695, MCHS; Vollmar, “The Negro in a Midwest Frontier City,” 70-72.