As an administrative law judge hearing worker’s compensation cases in Wisconsin for three decades, Joe Schaeve said he often knew how certain doctors hired by employers and insurance companies would rule even before opening their reports.

“It winds up with the doctor saying ‘Not work related’ or ‘It’s all in his mind,’ ” said Schaeve, who retired in May. “You can almost sense it coming when you spend 30 years reading these reports.”

Schaeve said a few of the experts’ opinions were so predictable that “it’s almost a waste of time to read the report because you know what it’s going to say.”

The opinions came from “independent medical examiners,” or IMEs. These doctors are hired by employers or insurance companies seeking to dispute claims for lost wages, extent of disability, loss of earning capacity and necessity for treatment.

Such claims can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars for severely injured workers and can increase the cost of worker’s compensation insurance for employers. Employers can use IME decisions to deny compensation to injured workers, forcing them to fight for their benefits.

In Wisconsin, IMEs do not need to be licensed by the state, so some of them travel from outside the state.

Worker’s compensation is often called the “grand bargain” because it bars employees from suing for workplace injuries with few exceptions. In exchange, employers must pay for lost wages, medical care and any resulting disabilities, regardless of who is at fault for the injury.

But in a few hundred cases each year in Wisconsin, the extent and cause of those injuries is disputed. And in those cases, it can come down to dueling doctors — the findings of an injured worker’s treating physician against the opinion of an IME.

IMEs review medical records and in some cases examine the injured worker. As a judge, when he saw a report from an out-of-state doctor, “my antennae immediately pop up,” Schaeve said. “At first glance, it tells me the insurance company knows — underline knows — they’re going to get a favorable report.”

Some IMEs “fly in on their charter jet from Kentucky or whatever and they see 20 people for 10 to 15 minutes at a time, they dictate their reports on the plane ride back, and they just made $20,000,” said Luke Kingree, an attorney who represents injured workers in Eau Claire and Madison.

Several worker’s compensation attorneys interviewed by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism mentioned brothers Timothy S. and Thomas J. O’Brien as out-of-state orthopedic doctors who routinely work for insurance companies. Timothy lives in Colorado and Thomas resides in Tennessee. Phone messages, as well as faxes sent to the IME broker for whom they work, were not returned.

Both doctors’ findings have at times been rejected by the state Labor and Industry Review Commission, which decides appeals of administrative law judge decisions. In one 2008 case, the commission found Thomas O’Brien’s denial of the cause of a worker’s low back injury “incredible.”

“Dr. O’Brien opined that the sudden and dramatic onset of low back symptoms coincident with the work incident was unrelated to that incident, and was merely a manifestation of the applicant’s pre-existing degenerative disc disease,” the commission wrote. “This opinion is incredible. The applicant was lifting a heavy piece of equipment when he felt and heard a ‘pop’ in his back, and thereafter his low back symptoms worsened and persisted.”

In a 2016 decision, the commission rejected a finding by Timothy O’Brien denying that a worker had suffered a rotator cuff tear when the semi-trailer he was driving jackknifed. O’Brien’s opinion — seconded by another insurance company-hired doctor — contradicted several treating physicians and magnetic resonance imaging. “The … tear, shown in the MRI, provides objective proof of injury,” the commission found, ordering the employer to pay for the recommended shoulder surgery.

Both O’Brien brothers are licensed in the state of Wisconsin. In 2015, Thomas O’Brien was issued a private administrative warning after a complaint was filed against him, according to a state Department of Safety and Professional Services record obtained by the Center. The Tennessee Department of Health lists one $75,000 or more malpractice settlement involving Thomas O’Brien in 2008.

Timothy O’Brien, testifying in 2017 in a Wisconsin case, acknowledged that a fellow member of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons had filed a confidential grievance against him alleging a violation of that group’s standards for performing IMEs. He said the complaint, filed in 2012 or 2013, was “apparently” resolved.

Judge skeptical of IMEs

Schaeve said while he found both injured workers’ doctors and IMEs to be worthy of close scrutiny, he generally found treating physicians to be more reliable reporters of an applicant’s medical condition. That is because most IME reports tend to either support denial of the claim or find “the injured worker is really not as disabled as he claims he is,” Schaeve said.

These IMEs examined patients for as little as three minutes — or not at all, he said. They often found that the injury was pre-existing, or in some cases, that the symptoms were exaggerated or unrelated to a verified work injury or that the worker had already healed.

In recent years, judges in two Nevada cases have barred an IME from testifying because of his alleged “extreme bias” against injured patients that included disagreeing with treating doctors about 95 percent of the time. The neurosurgeon made $1 million a year from insurance companies, the Las Vegas Review-Journal reported.

Schaeve said increasingly, he has seen some IMEs go outside their roles as medical reviewers to aggressively attack the credibility of injured workers.

But even lawyers who are critical of IMEs say employers and insurers should have the right to hire their own experts to evaluate claims.

“The concept of an IME is a good concept,” said Jeff Klemp, an Eau Claire attorney who represents injured workers. “The Legislature created this rule that insurance companies can send an injured employee to a doctor of their choosing. And on its face, you think that’s a good idea, let the insurance company get an objective evaluation here.”

For some physicians, conducting such examinations is their main line of work.

In a 2012 deposition, Milwaukee-area IME neurologist Dr. Marc Novom said he conducted three to six IME exams a week at $1,000 to $1,500 each, charging thousands more for depositions.

In a separate case, Novom confirmed that 80 to 90 percent of his income came from IME work; in 2012, he estimated that income at least $450,000 a year. As part of a lawsuit over a vehicle crash, a Dane County judge ordered two insurance companies to turn over records about Novom’s practice. According to those records, Novom performed 941 IME exams between 2011 and 2015.

A woman answering the phone at Novom’s office said he is on vacation until May but that she would pass along a message seeking comment.

Klemp said such a financial incentive can color a physician’s evaluation of an injured worker.

“Every business has to turn a profit, doesn’t it? Now if the business was turning out IME reports that consistently favored employees or agreed with the employee’s treating physicians, that business would not survive very long,” Klemp said.

Bias on both sides

Recently retired Milwaukee attorney Bill Sachse, who represented insurance companies and employers, said he looked for credible physicians to “provide the best record in favor of our client.” Some of them, including the O’Briens, are based out of state.

“I’m trying to win the case, so I’m trying to find a doctor who will do a thorough review of the case, which means talking to the employee when he or she goes in for the exam and looks at all the other information provided to the doctor — all medical records and any other information that I think might be relevant to the issue at hand,” Sachse said.

He said IMEs typically make $1,500 to $2,500 for examining a worker and evaluating a case. But Sachse said some treating physicians also may have a financial incentive.

Wisconsin is among just six states where there are no set fees for treating patients under worker’s compensation. Powerful business interests are pushing lawmakers to create limits for such cases.

Sachse said he had a recent case in which a surgeon would have earned $200,000 under worker’s compensation to repair a work-related injury. But if it were found not to be work related, the charge would be $50,000.

“So the doctor offering the opinion favorable to the employee had $150,000 on the line in that case,” Sachse said. “Don’t you think he might have been biased? I think so.”

Samuel D. Hodge Jr., a professor of law and anatomy at Temple University in Philadelphia, said he sees bias on both sides. Hodge has studied the rights and responsibilities of IMEs toward patients across the country.

Hodge noted some attorneys for injured workers hire the same physicians over and over to treat their clients. And because of their training, doctors tend to believe their patients, Hodge said.

However, Schaeve, the retired judge, said he saw little bias by treating physicians.

“It’s been my experience … the very vast majority of those office notes and opinions are generally reliable and honest whereby I don’t detect any true advocacy on behalf of the treating doctor,” he said.

There is at least one important difference between the doctors on each side of these cases.

Doctors who treat patients have an ethical obligation to give competent care. But Wisconsin is among the many states where an IME is not considered part of a doctor-patient relationship, which means applicants cannot sue IMEs for medical malpractice if they misdiagnose an injury or illness.

“There are a number of cases in a variety of states, where people have gone in and they have a cancerous lesion and the doctor doesn’t tell them anything about it because that’s not the purpose of their IME. They’re just to see if the person can go back to work,” Hodge said.

Despite — or perhaps because of — what he perceives as biases on both sides, Hodge believes the adversarial system of dueling experts largely works because “I don’t know how else you would do it.”

“I line up my expert for the plaintiff, you line up your experts for the defendant, and then it becomes a battle of the experts. Who is the jury is going to believe?” Hodge said. “It all becomes a credibility question. It’s no different from who ran the red light? Who do you believe?”

The president of the New Hampshire-based Workers’ Injury Law & Advocacy Group said use of the term independent medical examiners can fool workers into accepting “biased” diagnoses and dissuade them from pursuing benefits to which they are entitled.

“They don’t go hire an attorney who knows the system … and then these workers are stuck in a system where they think because of an artificial name that they’re getting an independent medical examination when really it’s a doctor chosen by the defense,” said Amie Peters, president of WILG, which advocates for injured workers. “The concern is a worker just won’t pursue their rights.”

Some states have moved away from the term “independent medical examination.” In Mississippi, for example, it is called an employer medical examination. Delaware has banned use of the term in worker’s compensation cases when the physician is hired by an insurance company or employer. Violators are subject to a $500 fine.

Attorney Kingree has worked on both sides — earlier in his career representing employers and insurance companies and now representing only injured workers.

“There’s nothing independent about those doctors,” Kingree said. “A more appropriate name is defense medical examination or adverse medical examination.”

Employer-paid doctors carry weight

When Richard Decker was injured in 2010, his employer, Kohler Co., where he had worked for 36 years, required him to be seen by two doctors it paid, including Novom. Decker was knocked unconscious by a toilet weighing at least 80 pounds. More than seven years later, he remains unemployed, relying on Social Security Disability Insurance — less than half of his former salary.

While four treating physicians said they believed Decker was fully and permanently disabled, both Kohler-paid doctors concluded that the shooting pains, memory loss, stuttering, frequent crying, headaches and severe cramps that Decker reported were mostly in his head.

Novom chalked up the Sheboygan County man’s symptoms to concern over the health of his wife, who had undergone a kidney transplant; depression; post-traumatic stress disorder and “poor academic performance and psychosocial deprivation growing up in a rural farm area.”

Novom used similar reasoning for a woman with a head injury from a work-related car crash. The woman reported “stabbing sensations in her head,” and problems with memory and mental slowness years after the 2006 injury.

Novom — contradicting three of the woman’s doctors and one physician hired by her employer — opined that the symptoms were not related to the crash but likely reflected an “undercurrent of psychosocial unrest” caused in part by the death of her husband in 2012. The LIRC rejected that opinion in its 2015 decision.

“The commission is not persuaded by (Novom’s) premise that the applicant is a ‘particularly fragile and emotionally wounded individual,’ ” the panel wrote. “That observation does not square with the applicant’s actual work history.”

Decker’s wife, Cathy, said she argued with Novom during one of the exams over what she believed was an inadequate assessment of Richard’s myriad symptoms.

“He basically said that (Richard’s) inability to remember how to write some things was because he was not very smart,” she said. “Pretty much called him stupid.”

Administrative Law Judge Sherman C. Mitchell sided with Decker and his doctors. But the LIRC overturned Mitchell, finding in its 2016 decision that Novom and another IME were more credible.

Sachse represented Kohler. He declined to discuss the case except to say that the outcome was “fair” and that during a couple of decades working with Novom, he found the neurologist to be “very professional, completely thorough.”

OSHA: Worker’s comp system ‘broken’

There are questions about whether the “grand bargain” of worker’s compensation continues to hold. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration concluded in a 2015 report that the worker’s compensation system is “broken,” with employers and insurers covering just 21 percent of the cost of the estimated 3 million serious workplace injuries and illnesses a year.

About half of the cost is borne by the injured workers, OSHA found — plus a 15 percent decrease in future earnings — while taxpayers, through programs such as Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security, paid at least 16 percent of the cost.

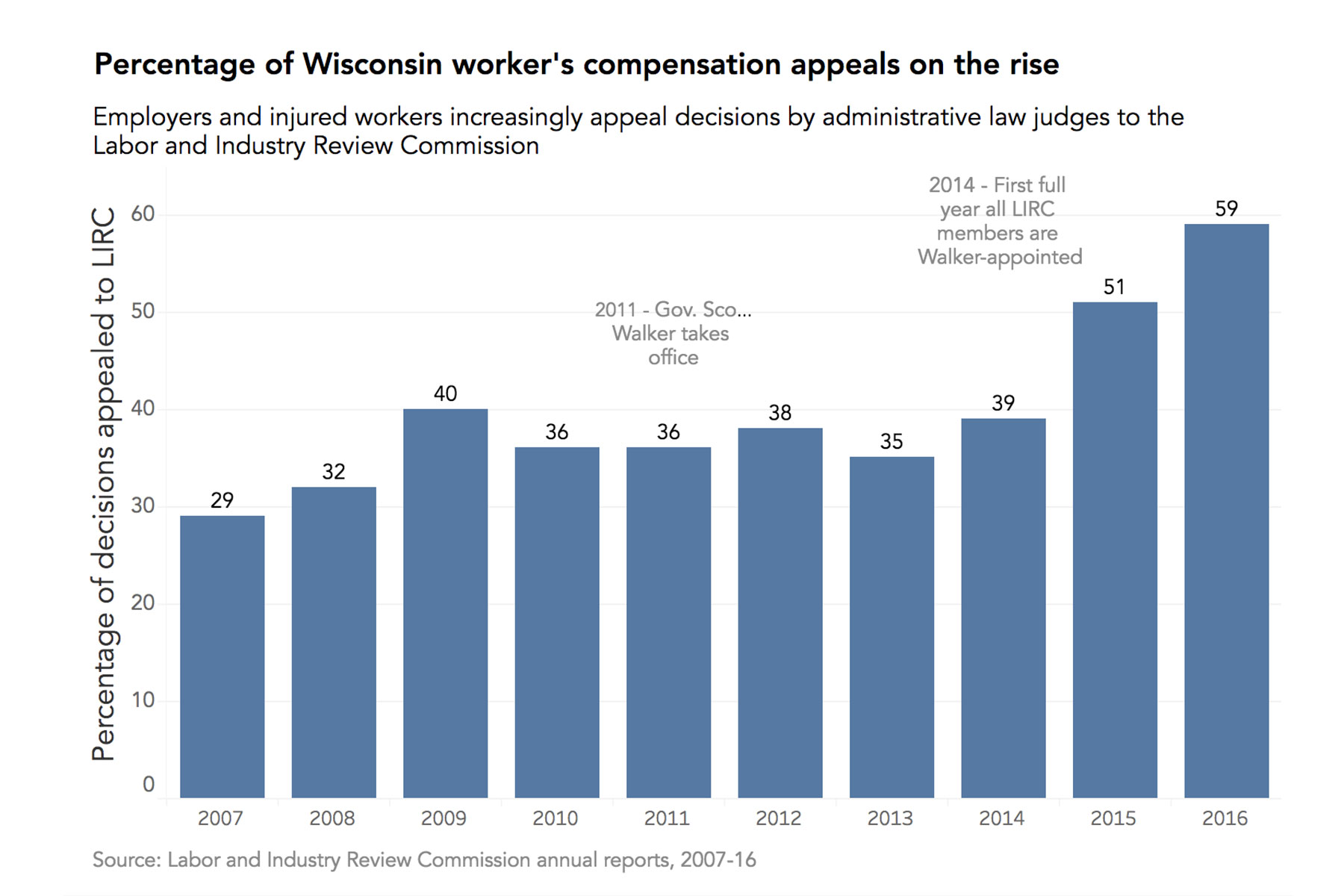

A recent story by the Center featuring the Deckers found other problems. Although Wisconsin’s system is one of the oldest and most respected, the Center found injured workers have faced a harder time qualifying for worker’s compensation in front of Gov. Scott Walker’s Labor and Industry Review Commission.

Schaeve said he and the political appointees on the LIRC sometimes reached opposite conclusions when it came to the extent and cause of a worker’s injury.

“There are times where I wondered, did we read the same set of medical evidence?” Schaeve said. “Or did we — LIRC and I — look at all the same facts and evidence in the case? Because it looks like all the evidence and the outcome they came out with is foreign to what I came out with.”

Alexandra Hall and Dee J. Hall

Alexandra Hall

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.