The contentious 2016 presidential election raised religious and racial tensions, but experts say the fears fueling hate and bias incidents began years earlier.

The reports came in at an alarming pace. A student at a middle school near Milwaukee drew a stick figure with a swastika on its face. The image held a gun pointed at another stick figure, which had the name of the student’s Jewish teacher on it.

A voicemail left on the phone of a leader of a local Jewish organization said, “Pack up your bags with all of your other kikes and get the f*** out of our country.”

These are just two of dozens of similar incidents compiled since the beginning of 2017 by Elana Kahn, director of the Jewish Community Relations Council of the Milwaukee Jewish Federation. She has been collecting information about anti-Semitic incidents in Wisconsin for the past seven years.

The barrage of anti-Semitism in Wisconsin has stunned Kahn.

“I have never had so many reports (about anti-Semitism) as I have had in the last couple months,” she said. “There’s more fear in our community now than there was even a year ago.”

Experts who study hate and bias-related acts say the incidents are part of a nationwide trend that has created tension in communities, schools and workplaces.

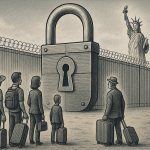

“The Trump presidency has emboldened a lot of these groups,” said Arno Michaelis, a former white supremacist from Milwaukee who now works to heal racial divisions through his group, Serve 2 Unite. “Having an administration that is blatantly anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim is basically enacting policies that are in line with white supremacy ideology. The narrative of white supremacy is that there are too many immigrants in our country. Trump’s policies reflect that attitude.”

Experts say while white supremacist individuals or groups may have divergent interests, many of them share a common agenda: They see the increasing diversity in the United States as a threat to their race. And the roots of their fear stretch years before the election of Donald Trump.

“(Former President Barack) Obama in a way was a physical representation of our changing demographics,” said Heidi Beirich, director of the Intelligence Project at Southern Poverty Law Center. “The rise in hate groups started in 2000, and that’s the year when the census said white people will become a minority in 2040s.”

And Trump supporters, such as National Review Online contributing editor Deroy Murdock, contend that tying Trump to white supremacy is no more than a cynical political ploy.

“The ‘Donald Trump = David Duke’ narrative is a bright, shining, left-wing lie,” Murdock wrote in a September column, referring to the former Ku Klux Klan leader. “It’s designed to make Trump radioactive, sandbag his agenda, and terrify black voters so they’ll stampede the polls and save the Democrats’ bacon in November 2018. The Left deserves universal scorn for deploying such political plutonium.”

In recent months, the nation has been roiled by racially charged protests and speeches, prompting former president George W. Bush to call on the public to reject white supremacy and racism.

“Bigotry or white supremacy in any form is blasphemy against the American creed,” Bush said during an Oct. 19 speech at Bush Institute’s Spirit of Liberty event in New York City. “Bullying and prejudice in our public life sets a national tone, provides permission for cruelty and bigotry, and compromises the moral education of children.”

The Southern Poverty Law Center, an Alabama-based nonprofit which tracks hate crimes and hate groups nationwide, said it has seen a rise in the number of hate groups operating in the country for the second consecutive year, up from 892 in 2015 to 917 in 2016. Nine of them operate in Wisconsin.

The center also attributes this spurt of hate group growth to the rise of Trump and his inflammatory rhetoric during the presidential campaign.

“He played into racist instincts,” Beirich said. “They (white supremacist groups) view Trump as a good political force for their beliefs.”

Alix Olson, a retired Madison Police Department detective who founded the organization Seeking Tolerance and Justice Over Hate, said that Trump’s election has emboldened hate groups “who felt before that they didn’t have a voice.”

“This administration has given carte blanche to white supremacy,” Olson said. “Everything is starting to become undone to the detriment of people who have way less power than white people do.”

State home to neo-Nazis, anti-gay groups

Among the nine identified hate groups in Wisconsin are the White Boy Society, a “biker brotherhood” that aims to protect the heritage of white people; Pilgrims Covenant Church, which preaches against gays, lesbians and transgender people; Nation of Islam, a black separatist organization whose inclusion in the list is, the center acknowledges, controversial; and White Devil Social Club, which the SPLC says fits the definition of neo-Nazi groups, which hate Jews, love Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany.

Like other groups reached for this report, the Nation of Islam rejected the “hate” label. It pointed to a column published by a New York-based African-American news website that described Nation of Islam as a “religious group with an impeccable track record of good works and service, particularly to the black community and other oppressed and marginalized communities throughout the country.”

Another organization, the National Socialist Movement, seeks to “defend our future from the genocide being pushed to wipe out the white race with race mixing,” according to Will Docks, the leader of the movement’s Wisconsin branch, which unsuccessfully sought to organize a rally in Eau Claire in September.

The Southern Poverty Law Center says the National Socialist Movement is “one of the largest and most prominent neo-Nazi groups in the United States.”

Docks described the group this way: “We believe in the success and empowerment of the white race, as other races do for their own. We don’t get motivated by attacking other races, we simply stand up for our race and to see that we survive and stand strong … now and in the future.”

Some groups not listed by the SPLC are controversial, but hard to categorize. For example, the Proud Boys, a group of “Western chauvinists” was founded by Gavin McInnes, who is anti-Islam. Leaders of the group threaten to sue anyone who calls them white supremacists or neo-Nazis.

The overall number of hate groups in Wisconsin and their members and activities are hard to track because some of these organizations operate without centralized leadership, fall apart quickly and function entirely online.

Wisconsin has not seen any high-level protests like the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August, in which one protester was run down and killed by a white supremacist. But the state is not immune to hate and bias events, ranging from merely disturbing to deadly.

A recent example: A white elderly patient in Ozaukee County, who was suffering from a life-threatening infection, asked a female doctor whom he had not previously met, “What’s that thing on your head?” After she informed him it’s called a hijab and she wore it because she is a Muslim, he ordered her out of the examining room.

The doctor, who asked that her name not be used, was astounded. She has been practicing in hospitals in the Milwaukee area for the past eight years. She said the incident in February was the first time a patient had refused treatment because of her religion.

“Will I say that I have never had the looks, the angry and dislike looks? Of course I did,” the doctor said. “But none that went as far as, ‘Get out of the room. I don’t want you to care for me.’ One more”

In March, a crime that police believe was racially motivated occurred in Junction City, a small community in central Wisconsin’s Portage County. Henry Kaminski, 80, fired a gun in the direction of a Hmong neighbor who was working in her garden because he thought the Hmong were taking over Junction City, according to news reports.

And then there is the case of Daniel Dropik who was convicted in 2005 of setting fires at two black churches — one in Milwaukee, the other in Lansing, Michigan. About 12 years later, when he was a student at University of Wisconsin-Madison, Dropik tried unsuccessfully to form a local student chapter of the American Freedom Party. That group seeks to “deport immigrants and return the United States to white rule,” according to the SPLC.

One of Wisconsin’s most infamous hate crimes occurred in 2012. On a quiet Sunday morning, a white supremacist walked into the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin in Oak Creek, shot six people dead and wounded four others. He thought he was killing Muslims, according to police.

No reliable data

There are no reliable data on the number or rate of hate crimes in the United States, according to the investigative news nonprofit ProPublica. The organization has collected several dozen self-reports of alleged incidents of hate and bias in Wisconsin — most of them unconfirmed — since November 2016 when it began soliciting tips as part of its Documenting Hate project. The Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism is among more than 100 news outlets and other groups participating in the project.

Official statistics of hate crimes in Wisconsin appear to show a number that has stayed relatively the same. The Wisconsin Department of Justice reported 48 hate crime-related incidents in 2012. That number slightly increased to 53 in 2013, and then began to decrease to 51 in 2014, 45 in 2015 and 41 in 2016, according to FBI data reported by the DOJ.

These figures are based on what is reported to law enforcement agencies, not on what is prosecuted. Prosecutors face a high burden: They have to prove the suspect’s actions were intentional and were directly motivated by animus towards the victim’s religion, national origin, race or other characteristic.

Scholars and experts who study hate crimes say the FBI hate crime data are unreliable due to the discretion local law enforcement agencies have in reporting such crimes. The victims’ hesitance to call the police to report about what happened to them may also contribute to the discrepancy. And some of the incidents may be frightening or disturbing but do not rise to the level of a crime.

“One of the reasons that they don’t want to talk to law enforcement about hate crimes is because they don’t trust the police,” said Olson, the retired detective. “Or they have had a bad experience previously with the police. Or they have seen the police react negatively or brutalize people in their community and they don’t want to have anything to do with them.”

Some people instead turn to citizen groups or organizations like the Milwaukee Jewish Federation, whose anti-Semitism data vary widely from that of the Wisconsin Department of Justice.

FBI figures show just eight anti-Jewish hate crimes in 2016 in Wisconsin, while the same year the federation collected 50 anti-Semitism reports, some of which do not rise to the level of criminal behavior. These reports include harassment or threats, written and verbal expressions or vandalism, such as the swastikas that were spray-painted on a memorial near the Gates of Heaven synagogue in Madison’s James Madison Park in September.

The vandalism came hours before the celebration of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year.

“It was obviously a targeted attack meant to intimidate a community,” Olson said, “and knowing that swastikas do to the Jewish community what Confederate flags do to the African-American community.”

At UW-Madison, 11 percent of 8,652 students surveyed in 2016 in the first campus-wide climate survey said they have been subjected to hostility, harassment or intimidating behavior. Students of color, women, transgender people, those with disabilities, gays and lesbians were more likely to experience such incidents, according to the climate survey.

The campus also has seen an increase in reported incidents of harassment and bias.

From August to December 2015, there were 18 hate and bias incidents reported to the university’s Bias Response Team. But in the first half of 2016, that number more than tripled to 66, according to data from the university. And in the last half of 2016, that number jumped to 87. The university said the increase could be due to more awareness and the electronic bias reporting system the university launched three years ago that makes it easier to report incidents.

Most reports were about racial insults, so-called microaggressions, derogatory language, signs on bulletin boards or graffiti found on campus buildings.

They also included exam questions that some students had found troubling, such as when a statistics instructor asked students during the spring 2016 semester to solve a problem involving kangaroos jumping over the U.S.-Mexico border. The teacher wanted to know how high the border wall should be so that kangaroos won’t be able to cross the border. Three Mexican-American students who were offended by the question filed a hate and bias report.

“Given the political rhetoric at the time, it came to our attention and it was like, ‘Yeah, that’s a bit insensitive,’ ” said Kevin Helmkamp, UW-Madison’s assistant vice provost and associate dean of students. “The teacher acknowledged that it was not a good question.”

When members of the university community file a report, the Bias Response Team meets with impacted individuals to try to come up with a resolution, Helmkamp said. The team also holds support meetings and bias training workshops.

“There’s a lot pain out there right now, and it’s a challenging time for our society as a whole,” Helmkamp said.

One of the communities feeling that pain is Native American students. In March 2016, a group of students mocked tribal leaders at the Dejope Residence Hall during a healing ceremony held for sexual assault victims. And this year, on Oct. 9, Indigenous Peoples’ Day, graffiti that read “Columbus Rules 1492” was written in red paint on a sacred fire circle at the same hall.

Native American students say the desecration reminds them of centuries of discrimination in a place that is supposed to welcome them.

“Every time we go there now, it’s going to be in the back of our minds that that happened there,” said Collin Ludwig, co-president of Wunk Sheek, an indigenous student group. “It’s just disappointing and it upsets us a lot that we are still being treated this way after 500 years.”

The students say if the vandalism had happened on another day, it would have been less hurtful.

“You can tell it comes from a place of hate when it’s done on a day so significant to us,” said Mariah Skenandore, co-president of Wunk Sheek. “There’s so much hate behind it when you are intentionally putting a damper basically on the day that was meant to celebrate us.”

The celebration Wunk Sheek had planned that day proceeded, with students holding a “celebratory” potluck. But, said Skenandore, “My heart isn’t safe on this campus.”

“It’s terrifying for me to walk down the street and not know who even committed a crime like that or who is capable of doing that or who agrees with the person that did that or doesn’t see anything wrong with that,” she said. “I could be walking side by side with these people.”

The students wonder where the hate comes from. They say they have been hurt for so long; one more insult will not stop them from celebrating their culture.

In a way, Skenandore said, she feels sorry for the people who defaced the sacred space.

“We are resilient people,” she said. “We are going to persevere. But at the end of the day, they are hurting more than us.”

Mukhtar Ibrahim

Jeff Glaze, Michael Sears, Jacob Byk, and Alexandra Hall

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.