“It was this conjunction of three Rivers at the lakefront that put Milwaukee on the map. We are here, Milwaukee exists, because of water. It is just that simple.” – John Gurda

Historian John Gurda honored the United Nation’s World Water Day on March 22 by hosting a tour through Milwaukee, celebrating the city’s history and foundation around water. The 22 mile route covered more than two hundred years of history, following the waterways that the communities and industries of Milwaukee grew around. From the shore of Lake Michigan, to the Milwaukee River, Menomonee River, and Kinnickinnic River, water was a necessity for every aspect of Milwaukee life.

“Milwaukee Water Bus Tour with John Gurda” was one of the Water Week events presented by the City of Milwaukee and its partners, to recognize all the public, private, and non-profit efforts underway to make Milwaukee a Water Centric City. John Gurda has been “doing” history for 44 years. He joked that if he were to write a memoir today, it would be called “44 years of 1099s” because he has been freelancing for a really long time. He is currently working on a book for the Wisconsin Historical Society called “Milwaukee: A City Built on Water.” In backwards fashion, it is based on a documentary that PBS aired two years ago.

This feature includes a map with photos from the event, and images taken separately of the tour areas, along with quotes of interest from Gurda from this first of its kind tour.

“The Global Water Center in the Menominee Valley is the epicenter of Milwaukee’s vision for being a hub of global water technology. Since it opened for years ago last September, there has been an amazing transformation. And that energy is spreading out to Read Street Yards, which is a city developed business park with an emphasis on water related businesses. The area was just a freight yard and tracks, and not a whole lot of work going. But now it is part of a greater resurgence of interest and investment.”

“It is hard to imagine what used to be Menominee River back in the early years of native settlements. It was a half mile wide and four miles long, with reeds, brushes, cattails, and beds of wild rice. In the Chippewa language, Menomonee literally means ‘rice eaters,’ so this was a garden, grocery store, transportation route, church, and supply supply center for native people. In those early years there were at least seven villages within two miles of downtown. Every one of them had access to water, so being built on water began really early in the history of the area.”

“In my new book, I am just finishing a chapter called “Singing the Dirty Song.” It is the job of MMSD (Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District) to make that song a lot cleaner. It works to protect Lake Michigan and all its tributaries. Since the deep tunnel opened back in 1993, they have treated a long-term average of 98.5% of Milwaukee’s waste water. The national standard is 85% so MMSD is way ahead of the game.”

“Looking at a map of the Great Lakes, in virtually all the major settlements were based at a river mouth. Back in the day when they were established, people arrived by schooners. There is this all-water route from the East Coast at Albany on the Hudson River, to Buffalo at Lake Erie. So people could sail to the Great Lakes, and all the way down to Chicago. That journey might have taken two months, but it was faster than trying to drag your goods across the world and into to the American heartland. We have a 1,000 mile route all-water route to the interior. So water is absolutely a Milwaukee lifeline, going way back to the very earliest years. Much of the lakefront area was wetland, from downtown to the Third Ward and Walker’s Point. Some of the biggest civil engineering programs in the early years of the area were the landfills or ‘made land’ as it was called.”

“Even twenty years ago in Milwaukee, the 6th Street Viaduct was the most forlorn bridge in city. It still had the streetcar tracks on it, because no one thought enough to take those out. It went right over the Menomonee Valley and the intent was to get over the valley and get out of the area. Under John Norquist’s administration, who was mayor from 1988 to 2004, he had to burn some political capital to create a kind of Calatrava inspired design for a new 6th Street bridge. Then the intention was to bring people down to the Menomonee Valley, so it opened the door. No one could have imagined that Harley-Davidson would spend millions of dollars in 2006, at the site of an old DPW yard, to build a museum to tell their story.”

“Canal street was aptly named because it was a network of canals. It is also the baseline for Milwaukee’s address numbering, zero hundred. Facing West, to the left everything is a South address, and to right are North addresses. It is the very center of Milwaukee. The other impact that the Menomonee Valley had was it divided the Southside from everything else. While the North territory was subdivided by east and west and smaller enclaves, the Southside has always just remained the Southside. So it is much more monolithic than other sections of town.”

“Because of the canal system, the Menominee Valley became the industrial center of Milwaukee, on a par with the Ruhr valley in Germany. It was home not to thousands but tens of thousands of jobs. Almost like a bucket brigade, a stream of workers would pour in at the start of every day and then pour out in the afternoon. The Menominee Valley would breathe in workers and then breathe them out again. They would walk from as far south as Lincoln Avenue and as far north as North Avenue, or take the streetcar. The area had a huge concentration of employment.”

“After the 1950s, as people start moving out to the edges and highways replaced trains, the area became what is called a derelict industrial zone. But it was always known as a kingdom of shrieks and smells due to the slaughter houses.”

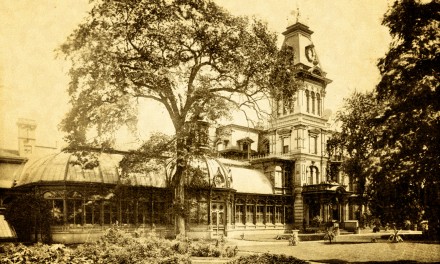

“By the Mitchell Park Domes, there is a second hill that the kids call “suicide hill.” That is where Jacques Vieau put his trading post way back in 1795. It is considered by some to be the first white settlement in Milwaukee.”

“Milwaukee’s smallest neighborhood is Pigsville. It has about 250 households with 11 Streets, and 7 and them are dead ends. So people do not get there unless they live there or they are lost. I did a book back in the 1980 for UWM about three neighborhoods called “The West End, Merrill Park, Pigsville, Concordia.” I tried really hard to find out where that name came from. There were lots of inventive explanations. One was that the river has a really sharp bend and the theory went that when the rain came down really hard it would wash pigs off farms up in Wauwatosa. They came down river and then when the current slowed because it had to make the turn, the pigs just kind of wonder up into the neighborhood. Another theory was that sometimes trains taking pigs to market would derail at the same curve, so they would wander up. And another was that a man named George Pigg had stagecoach stop there, but I found nothing to prove he existed.”

“The Milwaukee River used to be an open sewer, and that is not a metaphor. Back in 1888, Milwaukee dug a tunnel under the Eastside and built a flushing station. It is now the Colectivo Coffee Lakefront Cafe. It had the world’s largest water pump, which was built by a company that would later be known as Allis-Chalmers. The system used fresh lake water to flush the putrid river, and that made it really clean for a while. But there was still a problem with where the water was going. The city had these outbreaks of what they called intestinal flu, which was Typhoid fever. So there were these Third World health problems happening in Milwaukee. They begin chlorination of the water back in 1910. Chlorine has a habit of not breaking down as well in frigid water. So in the wintertime the water is 33° and people are ingesting straight chlorine from the water. There was a breakdown in 1916, with the chlorine system being shut off for about 10 hours. As a result, there were 60,000 cases of diarrhea and 50 dеаths from Typhoid fever. It was horrendous, which is why the sewage treatment plant was greeted with such celebration when it opened in 1925.”

“The area around Brady Street has rather distinctive housing, because that portion of land had an open stretch from the neighborhood into downtown. It was there was because people could walk to work at jobs along the riverfront industries. It was very important economically, but a disaster ecologically to have those factories on the Milwaukee River. Untreated sewage from Milwaukeeans, along with manure dropped on the streets every day from horses, made it nasty. At one point there was a newspaper headline ‘River to be made sewer.’ They had no way of treating the water and people were dying of intestinal diseases. The houses had their drinking wells for water and out-house toilets in the same backyard. At the time, there were no options to correct the problem.”

“Milwaukee engineers experimented for 50 years before they built the sewage treatment in 1925. Almost overnight it was treating, with an activated sludge method, 90% of the bacteria and 95% of the solids. The process was so profitable that it returned hundreds of thousands of dollars every year to the city of Milwaukee. That fertilizer is called Milorganite.”

“Commerce Street was a canal from the 1880s, so they filled it in and the road now is literally where the canal flowed. Originally, it was not a place you would have wanted to have a house near.”

- Milwaukee Water Week highlights Water Centric City initiative

- Research Vessel Neeskay: A vital tool for Great Lakes study

- Photo Essay: Cheers to being a water centric city

- Beers with the Mayor wraps up a successful Water Week

- Map: A City Built Around Water

- John Gurda hosts tour celebrating Milwaukee as a city built on water