In the modern media landscape, it is no secret that fans can develop an intense level of emotional attachment to public figures, fictional characters, and digital idols.

These attachments, often referred to as parasocial relationships, are essentially one-sided bonds where fans invest significant emotional energy into personalities who do not reciprocate that relationship in any concrete way.

Yet, it is precisely this unbalanced dynamic that has proven not only lucrative but is also systematically cultivated within the entertainment industry. The phenomenon is perhaps most strikingly seen among Japanese Anime enthusiasts known as “Otaku,” K-pop’s most fervent admirers that also includes the extreme subset known as “Sasaengs,” and video game players involved in “Gacha” game mechanics.

Through personalized content strategies, exclusive perks, fan events, and a constant stream of merchandise, companies have discovered that nurturing unhealthy parasocial ties is a highly effective way of driving revenue.

THE GENESIS OF PARASOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS

Social scientists first began examining parasocial relationships in the mid-20th century, noticing how television viewers and radio listeners spoke about media personalities as if they were close friends or acquaintances.

Today, parasocial relationships have migrated into every corner of the internet-driven era, and the entertainment industry has refined techniques to stoke those emotional connections. While traditional celebrity culture might rely on a veneer of inaccessibility, modern mediums turn that model on its head.

Instead, creators and companies foster an illusion of direct engagement through Twitter updates, livestream Q&A sessions, and meticulously crafted brand voices on platforms like TikTok and Instagram.

Such a sense of intimacy is more than an accident. It is central to how entertainment companies generate revenue. Fans who believe they share a “special” bond with their favorite idol or character are more likely to buy merchandise, stream music, attend live events, and spread brand awareness through social media.

That loyalty also translates into a willingness to forgive missteps by the creator or company, as fans cling to the idea of a deeper connection. Once that trust is established, the possibilities for monetization are virtually endless.

OTAKU CULTURE AND THE ANIME INDUSTRY’S CAREFULLY CRAFTED APPROACH

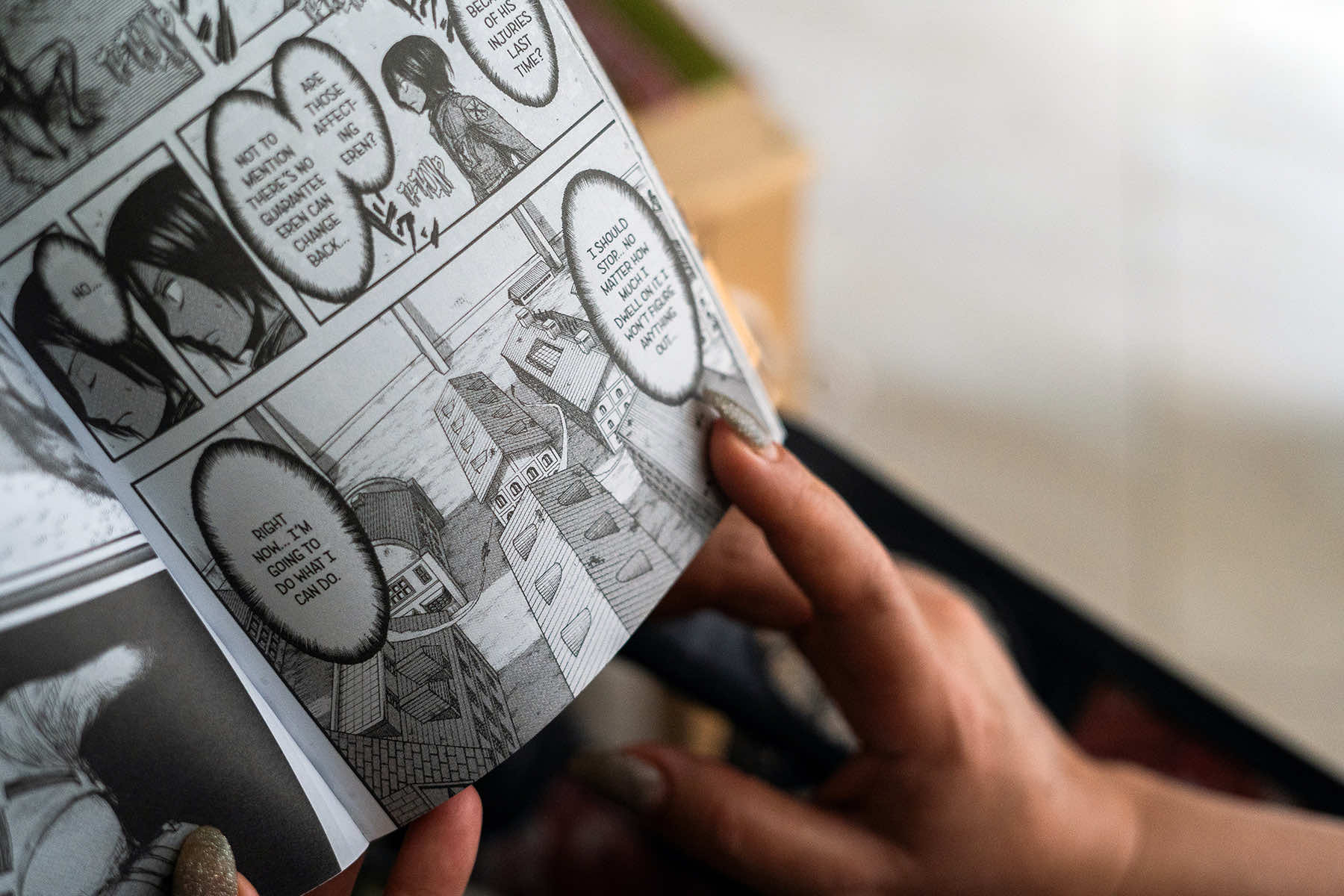

Japanese Anime culture, also known as Otaku culture, is a compelling case study of how companies cultivate and profit from parasocial relationships. On one level, Anime fans might feel a strong emotional connection to fictional characters from shows like the “Love Live! School Idol Project” or “K-On!” series that revolve around the lifestyles, struggles, and victories of endearing characters.

Through carefully planned story arcs, voice acting performances, and targeted marketing, fans begin to see these characters as more than fictional creations. Official social media accounts often post in the “voice” of these characters, blending the real world with the imaginary one, and blurring lines between creators, voice actors, and the fictional personalities themselves.

In addition, many Anime production houses and publishers organize fan events, such as meet-and-greets with voice actors, live concerts featuring the music from the show, and “character cafes” where fans can order drinks themed around specific characters.

Merchandising strategies range from collectible figures and artbooks to exclusive limited-edition products timed around birthdays or anniversaries of beloved characters, complete with countdowns and exclusive illustrations.

These events are not mere fan services. They are deliberate tactics that leverage the emotional investment fans develop. By nurturing the idea that a favorite Anime “idol” has a personal birthday a fan can celebrate, the industry ensures they associate the character’s milestones with real-life devotion. That dynamic inevitably leads to more purchases and public displays of loyalty on social media.

In the most dedicated corners of Anime fandom, fans may develop intense relationships with “virtual idols” like the cast of “Vocaloid” or Virtual YouTubers (VTubers). Livestreams featuring these virtual personalities often include real-time interactions. The heightened emotional stakes translate directly into larger expenditures and unwavering brand advocacy, creating a potent commercial cycle.

Fans who donate money or subscribe to membership programs might see their username flashed on-screen, sometimes followed by direct acknowledgments from the virtual host. This fosters the illusion of personal closeness with a two-dimensional character who greets fans by name and thanks them for their support.

K-POP’S SASAENG PHENOMENON AND INDUSTRY CUES

In South Korea, the K-pop industry has honed the practice of cultivating parasocial relationships to a near science. Idols are presented as both aspirational figures and quasi-friends who share selfies, post day-to-day updates, and speak directly to fans through livestreams.

The dynamic is central to K-pop fandom, where fans collectively call themselves a “family,” such as BTS’s “ARMY” or BLACKPINK’s “BLINK.” The personal dimension is so emphasized that a single tweet or Weverse post from an idol can spark days of frenzied discussion and fan-driven content creation.

While the vast majority of fans behave respectfully, Sasaengs represent an extreme subset who demonstrate obsessive, boundary-crossing behavior. These fans might camp outside idols’ homes, invade their privacy, and leverage technology to track flight information or personal schedules.

Many K-pop groups and their managing agencies publicly condemn such behavior, underscoring the importance of respecting idols’ personal spaces. However, the critical question is how certain industry practices may contribute to creating the conditions for these obsessive tendencies.

Companies often manage idol images down to minute details, ensuring that idols appear approachable, humble, and affectionate toward fans. Events like fan signs, “hi-touch” sessions where fans briefly meet and touch hands with idols, and VIP passes for exclusive meet-and-greets are standard and highly lucrative revenue streams.

These interactions reinforce the illusion that fans have intimate access to their idols, if only they pay enough or line up early. Consequently, it is not just albums and concert tickets that drive revenue. It is the promise of an emotionally fulfilling “closeness” that can be bought and sold.

While the fan-idol bond might look like unconditional love, it is also a carefully calibrated profit center. The result is an industry that frequently walks a precarious line between feeding parasocial cravings and maintaining idols’ personal safety.

GACHA GAMES AND THE DIGITAL ECONOMY OF AFFECTION

Video gaming is another arena in which parasocial relationships thrive, particularly in the realm of Gacha games. Gacha is a game mechanic, often found in free-to-play mobile titles, that uses random draws to acquire characters, gear, or other in-game advantages.

“Genshin Impact” is a prime example of a game that excels at leveraging character-driven appeal. Players do not merely see a collection of digital heroes on a screen. Instead, they build narratives around them, follow storyline events featuring the characters, and even invest real money to “pull” for that ultra-rare character they have come to adore.

Game developers and publishers often bolster these emotional ties by releasing character trailers, hosting “birthday celebrations” within the game, and incorporating limited-time events that flesh out the characters’ backstories.

Similar to Anime strategies, the characters might thank the player for supporting them, mention the player by name, or appear in special storyline episodes that reinforce the sense of personal companionship. The deeper a player’s emotional investment, the more willing they are to spend money on microtransactions or in-game premium currency to unlock special skins, voice lines, or story events.

By design Gatach games foster fierce brand loyalty and an unhealthy type of emotional dependency. Gacha systems place a probability barrier behind the items or characters fans crave the most, encouraging repeated expenditures in pursuit of elusive “SSR” (Super Super Rare) additions that come with more promises that intensify feelings of attachment.

THE MARKETING MACHINERY BEHIND THE SCENES

It would be misleading to suggest that these industries stumbled upon the concept of parasocial monetization by accident. The success of media franchises today often relies on multi-level marketing ecosystems orchestrated by both creative and commercial teams. Consumer data analytics, social media listening tools, and influencer collaborations all work in unison to cultivate fan devotion.

When a new Anime is slated for release, for instance, publishers tease key visuals and schedule variety show appearances by the voice cast. Simultaneously, they drop exclusive merchandise pre-orders or reveal in-game collaborations if the franchise is also tied to a Gacha game.

K-pop agencies employ a similarly robust marketing apparatus. They use algorithm-friendly social media strategies that push idols to trend on platforms like YouTube and Twitter. The idols themselves might host weekly livestream segments to discuss everyday life, effectively blending the boundary between a private individual and a public persona.

Pre-orders for albums often bundle collectible photo cards, limited-edition postcards, or random inserts that encourage fans to buy multiple copies to collect them all. Each step in the promotional cycle is designed to deepen the perceived connection between the idol and their fans, turning an intangible emotional attachment into a tangible revenue stream.

Meanwhile, gaming companies proactively analyze player behavior, discovering which characters spark the most “engagement,” or which story arcs evoke the largest emotional investment. They refine Gacha rates, determine the frequency of special events, and introduce new characters specifically designed to appeal to popular archetypes, like cute, stoic, or edgy.

ETHICAL IMPLICATIONS AND FAN WELL-BEING

In an era where data analytics can pinpoint user preferences down to the subtlest detail, the cultivation of parasocial relationships becomes a calculated science. The commercial success of these parasocial marketing strategies prompts an ethical conversation.

While many fans take genuine joy in participating in the fandoms and feel a sense of community, there is a question of whether such relationships can become exploitative. For example, the Gacha mechanic preys on the gambler’s fallacy, encouraging repeated spending through the illusion of “winning” one’s favorite character.

Young fans of K-pop may go to extraordinary lengths to purchase merchandise or gifts meant for idols, sometimes taking on personal debt or neglecting other areas of their lives. On the entertainment side, idols and voice actors often face intense pressure to maintain a friendly, accessible persona 24/7, leading to burnout or mental health struggles.

A vicious cycle ensues where fans demand ever more intimate insights, and agencies encourage that demand for profit. Such an environment can breed unhealthy behaviors, as demonstrated by the extreme actions of Sasaeng fans or the persistent pay-to-win mechanics in certain Gacha titles. Companies may enforce boundaries, but their business models still rely heavily on fostering the very attachments that can escalate into problematic territory.

POTENTIAL PATHWAYS TO A HEALTHIER ECOSYSTEM

Despite the ethical pitfalls, parasocial relationships are not inherently negative. Many fans find valuable community, emotional support, and even creative inspiration through their devotion. The key lies in mitigating exploitative extremes.

For instance, regulatory bodies could enact clearer guidelines on microtransactions, especially in Gacha games, to ensure transparency about odds and spending limits. Some gaming companies have begun implementing “pity systems,” which guarantee that after a certain number of pulls, the player will receive a rare character, thereby reducing the financial risk.

In the realm of K-pop, agencies have been making strides to protect idols by limiting or refining certain fan events. Fan sign sessions are more closely monitored, personal data is not publicly disclosed, and schedules are guarded more securely.

Additional educational programs for fans, such as warnings about stalking laws and personal privacy boundaries, can gradually shift the culture away from obsession and toward healthier forms of support.

Similarly, Anime production committees can prioritize content disclaimers or disclaimers around commercial tie-ins, clarifying that while they cherish the fans, their fictional characters are constructs, not living companions.

Ultimately, parasocial relationships underscore the power of modern media to evoke profound devotion. They tap into a deeply human desire for connection and meaning, repurposing it for corporate gain.

In the worlds of Japanese Anime, K-pop, and Gacha-driven gaming, these one-sided bonds are not merely quirks of fandom culture, they are the engine driving significant profit. Fans become not just consumers but deeply invested stakeholders who pour time, emotion, and capital into an idealized relationship.

As consumers grow more savvy about how these relationships are fostered for profit, perhaps their economic power could be used to encourage more ethical business models, proving that genuine connection, even if largely imaginary, need not come at a steep psychological or financial cost.

© Photo

Chris Pizzello (AP), and Infantry David, Ned Snowman, Bud Haryad, Lilgrapher, Chomp Learn, Sam TL, Vector-X (via Shutterstock)