In April, “Milwaukee Independent” published a series of in-depth interviews, photo essays, and investigative reports that examined the enduring aftermath of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami, and subsequent nuclear disaster at Fukushima Daiichi.

From the revitalization of fisheries to museum exhibits that commemorate the tragic 3.11 event, and the painstaking decommissioning process to the spirited communities that persist against all odds, the Fukushima of 2024 offered a measured but hopeful vision for the future.

In the photojournalistic diary, “Journey to Japan: A photojournalist’s diary from the ruins of Tōhoku 13 years later,” the stark images of once thriving neighborhoods in the Tohoku region, torn apart by the monstrous tsunami waves, stood as a reminder of the disaster’s scale. After thirteen years, many houses remained abandoned, their rooms left exactly as they were that harrowing afternoon when the waves swept inland.

Although some cleaning and demolition had taken place before the series was documented, the eerie silence still carried a heavy weight. The passage of time did not obscure the aftermath from the raw and destructive power of natural disasters, and why the path to recovery that followed was slow.

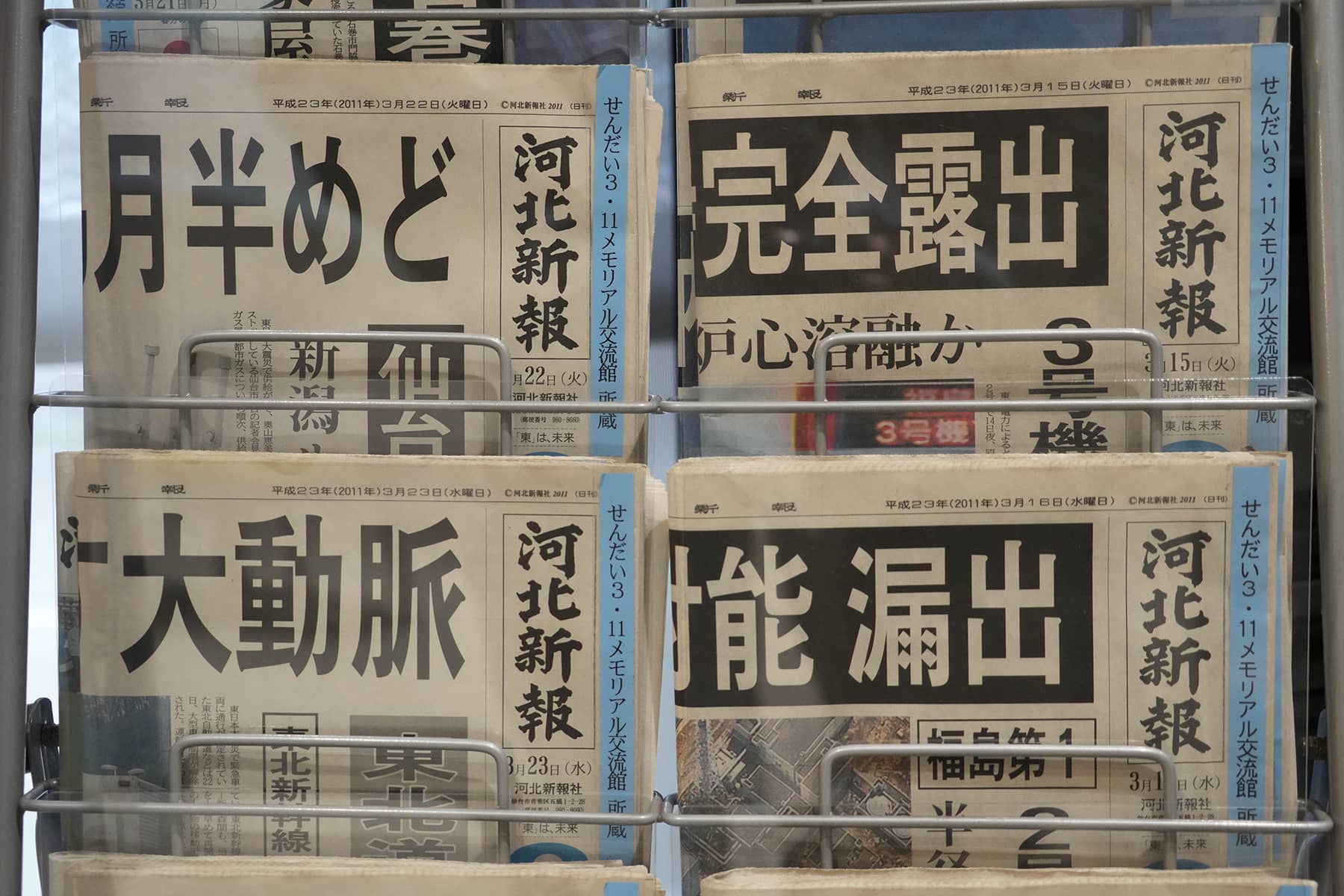

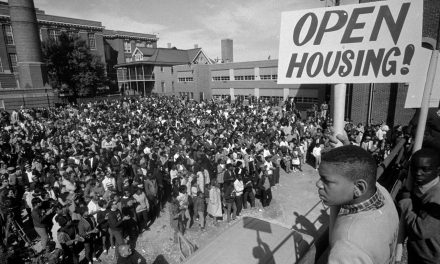

The article “Timeline of Tragedy: A look back at the long struggle since Fukushima’s 2011 triple disaster” expanded on that sense of collective trauma by placing the chaotic events in a historical timeline. Through a montage of archival images and new field photographs, readers were reminded of the immediate aftermath: families huddling in emergency shelters, rescue workers clearing the wreckage of entire seaside communities, and healthcare professionals confronting a crisis of unprecedented magnitude.

Despite widespread recovery projects, the piece emphasized the complicated reality that, while certain areas had been restored, others remained frozen in time. That was especially true for those in the radiation zone or along the remote coastline where post-disaster rebuilding had proven most challenging.

“New Year’s Aftershock: Memories of Fukushima fuels concern for recovery in Noto Peninsula” explored the deadly January 1, 2024 earthquake in the Noto Peninsula, and how initial reactions brought with it renewed anxieties about nuclear safety. Even in regions geographically distant from the reactor site, the resonance of the disaster stirred questions about long-term contamination, resource viability, and future preparedness.

That sentiment emerged again in “Fukushima’s Legacy: Condition of melted nuclear reactors still unclear 13 years after disaster,” which outlined the complex reality of monitoring irradiated cores and tackling the meltdown’s physical remains. Engineers and government officials had made strides in locating and analyzing nuclear debris, but the overall assessment remained hampered by technological and logistical hurdles.

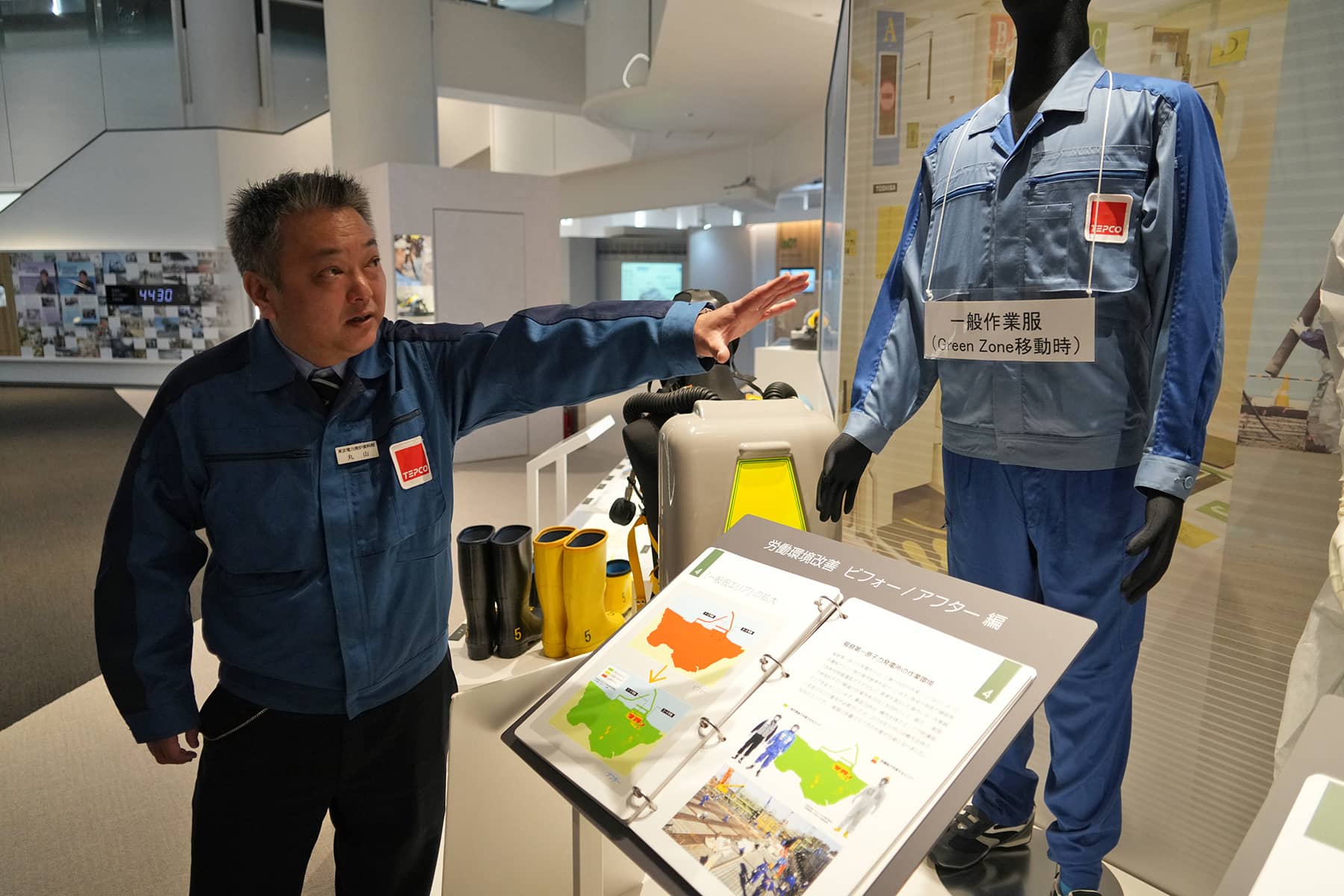

Contributing further to the discussion, “Technical Hurdles for TEPCO: Critics question 2051 deadline for decommissioning Fukushima,” highlighted the tension between public optimism and engineering realities.

Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) repeatedly reaffirmed its intention to complete the decommissioning of the crippled reactors by 2051. Yet experts voiced skepticism over the feasibility of meeting that benchmark.

Strained resources, the difficulties of handling nuclear waste, and the unpredictability of reaching radioactive areas deep within the plant have all cast a shadow on the timeline. In interviews with local residents, some expressed a willingness to be patient, acknowledging that thoroughness might be more important than haste, while others found the lack of concrete milestones exasperating.

For many outside Japan, Fukushima’s radioactive water release was the most scrutinized aspect of the plant’s decommissioning. In “Radioactive Waste: IAEA confirms water discharge from ruined nuclear plant meets safety standards,” the International Atomic Energy Agency’s official endorsement of the water discharge process sparked mixed reactions.

Fishermen in Fukushima, who have long battled international skepticism about the safety of their catch, viewed the news with cautious relief. Government officials also seized upon the IAEA’s endorsement to show that Japan was taking every precaution. Still, skepticism lingered among local grassroots activists and neighboring countries in Asia, reminding the world that “acceptable risk” remains a matter of perspective.

Parallel to these developments, local fisheries carved a path toward economic revitalization, as covered in “Seafood Safety: Profits surge as Japanese consumers rally behind Fukushima’s fishing industry.” Domestic consumers, emboldened by improved safety protocols, responded with a show of solidarity at fish markets and restaurants.

Fishermen cautiously welcomed the upward trend, attributing success partly to robust testing measures, partly to national pride in Japan’s maritime traditions. Images of bustling harbors, smiling vendors, and tables laden with fresh catch suggested that, in 2024, a crucial psychological shift had taken place. The sense of stigma once shadowing the label “Fukushima” in the fish market was slowly eroding.

Nonetheless, large swathes of Fukushima and Tohoku remain deserted. “In the shadow of silence: Exploring Fukushima’s abandoned lands that remain frozen in time,” the Milwaukee Independent photojournalist recounted trips through shuttered towns like Futaba, with empty homes lined up along roads that once teemed with daily life.

Weeds sprouted through cracks in concrete parking lots. Occasional bulletins, pinned to local notice boards, displayed relics of an era before March 11, 2011 – including calendars remaining frozen on that fateful day. The visuals evoked a ghostly stillness and documented how swiftly nature could reclaim territory when human presence recedes.

Part of the region’s emotional recovery has involved translating personal memories into institutional frameworks. “Spiral Staircase of Life: Tōhoku museums preserve echoes of March 11 for future generations,” chronicled the efforts of educators, historians, and survivors who joined forces to curate immersive exhibits.

Visitors could trace the timeline from the quake’s initial tremors to the chaotic aftermath. Objects recovered from debris, such as children’s toys, sodden photo albums, and clocks stopped at the time of the tsunami’s arrival, brought the scale of human loss into focus.

In “Lessons for future generations: Memorial Museum in Futaba marks 13 years since 3.11 Disaster,” the involvement of community volunteers served as a living link to the past. They guided visitors through artifacts and shared personal stories, ensuring that the tragedy’s narrative would endure.

While some walked away from Fukushima, others came back. “Retracing Our Steps: A review of the project that documented nuclear refugees returning home,” described the heartbreak and hope of those families who chose to return to the region after evacuation orders were lifted. The complexities they faced included property disputes, the limited availability of hospitals, and the constant worry about residual radiation. And yet, many cited an emotional tug, a longing for home that ultimately overpowered lingering fears.

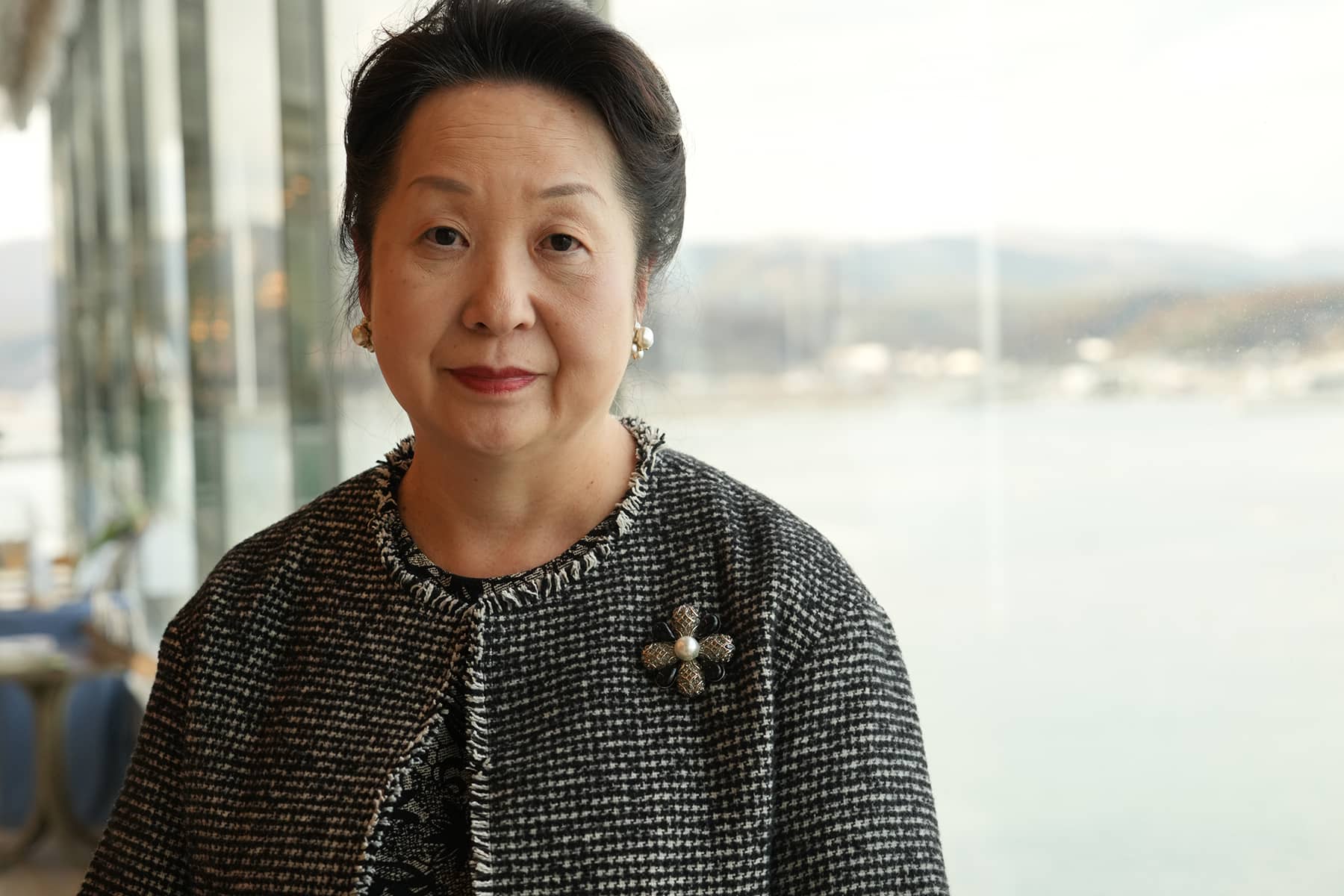

Such personal connections also emerged in profiles like “Noriko Abe: Continuing a family legacy of hospitality to guide Minamisanriku’s recovery.” Abe’s story became emblematic of an entire generation of local entrepreneurs determined to rejuvenate tourism and preserve cultural traditions. By reimagining family inns as community spaces, she not only kept an ancestral business alive but also put Minamisanriku on the map as a hub for volunteer tourism and sustainable recovery efforts.

Another glimpse of these grassroots efforts appeared in “Moai of Minamisanriku: How a bond with Chile forged a learning hub for disaster preparedness.” Here, the famous Easter Island Moai statue, gifted to the town by the Chilean government, grew into a symbol of international solidarity.

Cultural exchange programs taught disaster readiness, blending narratives of earthquakes in Chile with Japan’s experiences. By fusing local knowledge with global lessons, Minamisanriku presented itself as a prime example of how communities can unite across borders, building resilience that spans continents.

In “Focus on the Future: Futaba Project aims to rebuild dreams and repopulate its community.” local officials and residents expressed a cautious optimism. Some areas of Futaba were reclassified from “Difficult-to-Return Zones,” allowing families and businesses to reclaim properties. Rebuilding efforts demonstrated that these once-lost towns could evolve into models for sustainable, eco-friendly design.

A similar thread of renewal ran through the story of “Junko Yagi: Pioneering a grassroots revival of local businesses in rural Onagawa.” Yagi’s collaboration with artisans, fishermen, and farmers sparked a wave of small-scale entrepreneurship. These success stories underscored the meaningful synergy between tradition and innovation — something that Tohoku region communities have championed for over a decade.

At times, recovery has come hand in hand with profound personal quests. “Diving into darkness: The story of Yasuo Takamatsu’s search for his missing wife” offered one of the most stirring accounts in the series. Takamatsu’s devotion to locating his wife, who vanished on March 11, 2011, transformed into a mission that symbolized universal themes of love, closure, and resilience.

Year after year, he plunged into dark waters off the coast, refusing to abandon hope. His story illustrated how collective tragedy often coexists with intensely individual grief, reminding the world that the line between personal and communal narratives can be blurred.

Elsewhere, cultural heritage played a role in healing. “Solace and Sake: Chūson-ji Temple and Sekinoichi Shuzo share centuries of tradition in Iwate” depicted how religious practice and traditional brewing provided comfort, continuity, and a sense of identity. The region’s sake producers harnessed local ingredients to create products that blended centuries-old artistry with modern engineering. They also partnered with temple priests, offering rituals meant to honor ancestors and celebrate the present’s fragile joy.

In many of these dispatches, the scope extended beyond strictly nuclear issues. Pieces such as “Running into history: The day Milwaukee Independent stumbled upon a marathon in Tokyo” and “Roman Kashpur: Ukrainian war hero conquers Tokyo Marathon 2024 with prosthetic leg” reminded readers that Tohoku’s recovery was not insulated from global events or everyday human resilience. Marathon runners spanning multiple nationalities converged in the capital, championing personal triumphs that resonated with Japan’s quest for renewal.

The complexities of life across Tohoku were apparent in other stories as well. “From Rails to Roads: BRT offers flexible transit solutions for disaster-struck communities” showcased how a shift to bus rapid transit revitalized remote regions where traditional rail lines had been destroyed.

Meanwhile, “From Snow to Sakura: Japan’s cherry blossom season feels economic impact of climate change” noted that changing weather patterns had direct consequences for local tourism—a crucial pillar of Tohoku’s recovery. And in “Potholes on the Manga Road: Ishinomaki and Kamakura navigate the challenges of anime tourism,” creative campaigns to draw fans of Japanese pop culture stood side by side with infrastructure woes, illustrating the balancing act between welcoming visitors and maintaining local roads.

Even as Tohoku looked forward, many parts of Japan remained rooted in a deep respect for tradition. “The Ako Incident: Honoring the 47 Ronin’s legendary samurai loyalty at Sengakuji Temple” seemed, at first glance, distant from Fukushima’s hardships.

Yet, the shared sense of reverence across centuries, whether for samurai loyalty or for disaster survivors, underscored Japan’s collective capacity to remember, to pay tribute, and to learn. Though the circumstances differ, the 47 Ronin’s reverberating sacrifice has become an echo of cultural perseverance. It also serves as a valuable example of the Tohoku’s modern-day survival story.

As officials, scientists, and residents work to transition from short-term recovery to long-term sustainability, a new generation of voices is stepping forward. Local youth are forging grassroots initiatives, entrepreneurs are redefining agriculture and marine industries, museum curators are expanding the scope of memorials, and disaster-preparedness experts are sharing their knowledge abroad.

3.11 Exploring Fukushima

- Journey to Japan: A photojournalist’s diary from the ruins of Tōhoku 13 years later

- Timeline of Tragedy: A look back at the long struggle since Fukushima's 2011 triple disaster

- New Year's Aftershock: Memories of Fukushima fuels concern for recovery in Noto Peninsula

- Lessons for future generations: Memorial Museum in Futaba marks 13 years since 3.11 Disaster

- In Silence and Solidarity: Japan Remembers the thousands lost to earthquake and tsunami in 2011

- Fukushima's Legacy: Condition of melted nuclear reactors still unclear 13 years after disaster

- Seafood Safety: Profits surge as Japanese consumers rally behind Fukushima's fishing industry

- Radioactive Waste: IAEA confirms water discharge from ruined nuclear plant meets safety standards

- Technical Hurdles for TEPCO: Critics question 2051 deadline for decommissioning Fukushima

- In the shadow of silence: Exploring Fukushima's abandoned lands that remain frozen in time

- Spiral Staircase of Life: Tōhoku museums preserve echoes of March 11 for future generations

- Retracing Our Steps: A review of the project that documented nuclear refugees returning home

- Noriko Abe: Continuing a family legacy of hospitality to guide Minamisanriku's recovery

- Voices of Kataribe: Storytellers share personal accounts of earthquake and tsunami in Tōhoku

- Moai of Minamisanriku: How a bond with Chile forged a learning hub for disaster preparedness

- Focus on the Future: Futaba Project aims to rebuild dreams and repopulate its community

- Junko Yagi: Pioneering a grassroots revival of local businesses in rural Onagawa

- Diving into darkness: The story of Yasuo Takamatsu's search for his missing wife

- Solace and Sake: Chūson-ji Temple and Sekinoichi Shuzo share centuries of tradition in Iwate

- Heartbeat of Miyagi: Community center offers space to engage with Sendai's unyielding spirit

- Unseen Scars: Survivors in Tōhoku reflect on more than a decade of trauma, recovery, and hope

- Running into history: The day Milwaukee Independent stumbled upon a marathon in Tokyo

- Roman Kashpur: Ukrainian war hero conquers Tokyo Marathon 2024 with prosthetic leg

- From Rails to Roads: BRT offers flexible transit solutions for disaster-struck communities

- From Snow to Sakura: Japan’s cherry blossom season feels economic impact of climate change

- Potholes on the Manga Road: Ishinomaki and Kamakura navigate the challenges of anime tourism

- The Ako Incident: Honoring the 47 Ronin’s legendary samurai loyalty at Sengakuji Temple

- "Shōgun" Reimagined: Ambitious TV series updates epic historical drama about feudal Japan

- Enchanting Hollywood: Japanese cinema celebrates Oscar wins by Hayao Miyazaki and Godzilla

- Toxic Tourists: Geisha District in Kyoto cracks down on over-zealous visitors with new rules

- Medieval Healing: "The Tale of Genji" offers insight into mysteries of Japanese medicine

- Aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi: Finding beauty and harmony in the unfinished and imperfect

- Riken Yamamoto: Japanese architect wins Pritzker Prize for community-centric designs