As an Israeli ground offensive in the Gaza Strip looms in its most devastating war yet with Hamas, one of the greatest threats to both its troops and the 2.3 million Palestinians trapped inside the seaside enclave is buried deep underground.

An extensive labyrinth of tunnels built by the Hamas militant group stretches across the densely populated strip, hiding fighters, their rocket arsenal, and over 200 hostages they now hold after an unprecedented October 7 attack on Israel.

Clearing and collapsing those tunnels will be crucial if Israel seeks to dismantle Hamas. But fighting in densely populated urban areas and moving underground could strip the Israeli military of some of its technological advantages while giving an edge to Hamas both above and below ground.

“I usually say it’s like walking down the street waiting to get punched in the face,” said John Spencer, a retired U.S. Army major and the chair of Urban Warfare Studies at the Modern War Institute at West Point.

Urban defenders, he added, “had time to think about where they are going to be and there’s millions of hidden locations they can be in. They get to choose the time of the engagement — you can’t see them but they can see you.”

The Israeli military said on October 28 that its warplanes struck 150 underground Hamas targets in northern Gaza, describing them as tunnels, combat spaces and other underground infrastructure. The strikes — what appeared to be Israel’s most significant bombardment of tunnels yet — came as it ramped up its ground operations in Gaza.

WHAT THE PAST HAS SHOWN

Tunnel warfare has been a feature of history, from the Roman siege of the ancient Greek city of Ambracia to Ukrainian fighters holding off Russian forces in 15 miles of Soviet-era tunnels beneath Mariupol’s Azovstal Iron and Steel Works for some 80 days in 2022.

The reason is simple: tunnel battles are considered some of the most difficult for armies to fight. A determined enemy in a tunnel or cave system can pick where the fight will start — and often determine how it will end — given the abundant opportunities for ambush.

That’s especially true in the Gaza Strip, home to Hamas’ tunnel system that Israel has named the “Metro.”

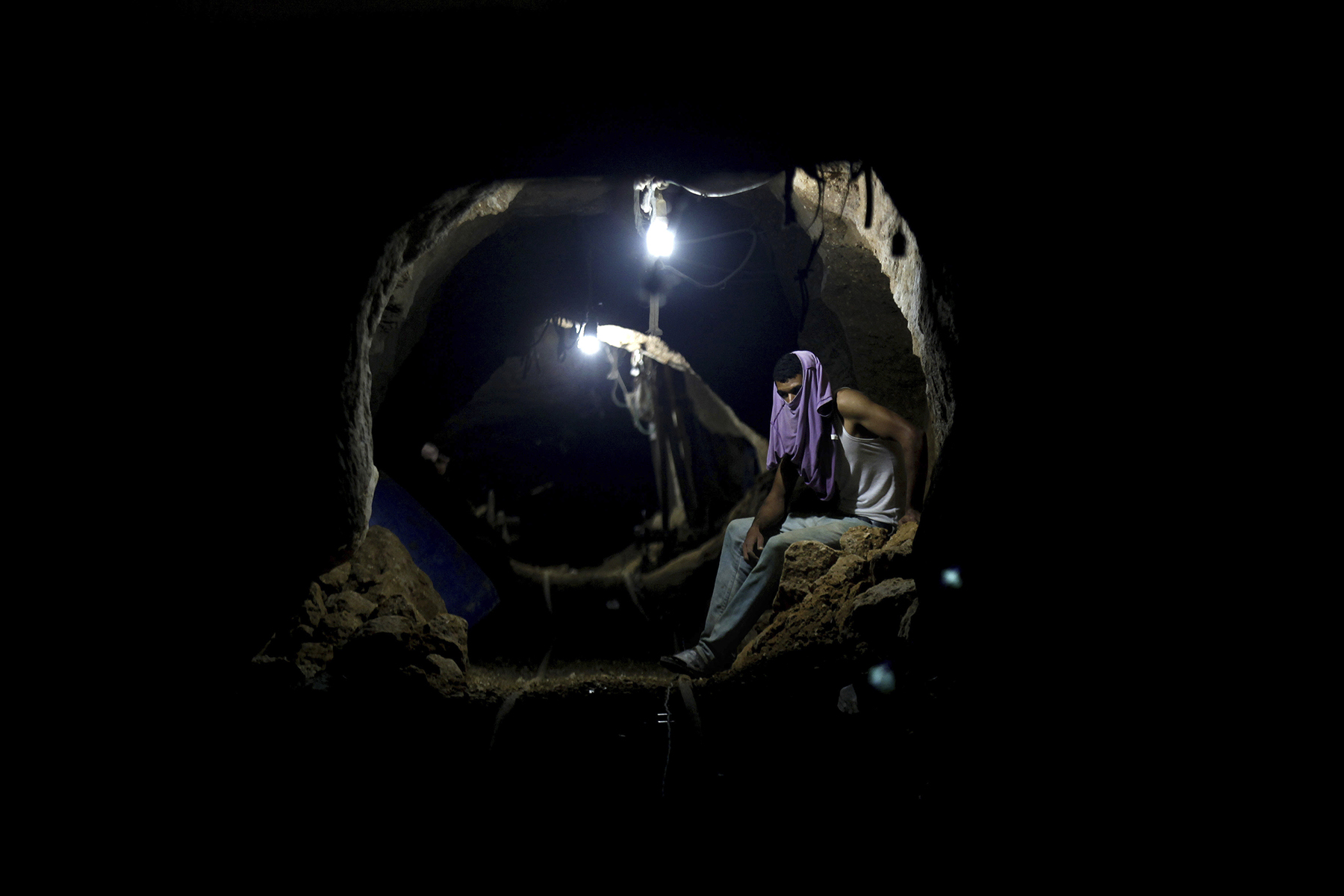

When Israel and Egypt imposed a punishing blockade on Gaza after Hamas seized control of the territory in 2007, the militant group expanded construction of its tunnel network to smuggle in weapons and other contraband from Egypt. While Egypt later shut down most of those cross-border tunnels, Hamas is now believed to have a massive underground network stretching throughout Gaza, allowing it to transport weapons, supplies and fighters out of the sight of Israeli drones.

Yehiyeh Sinwar, Hamas’ political leader, claimed in 2021 that the militant group had 500 kilometers (310 miles) of tunnels. The Gaza Strip itself is only some 360 square kilometers (140 square miles), roughly twice the size of Washington, D.C.

“They started saying that they destroyed 62 miles of Hamas tunnels. I am telling you that the tunnels we have in the Gaza Strip exceed 300 miles,” Sinwar said following a bloody 11-day war with Israel. “Even if their narrative is true, they only destroyed 20% of the tunnels.”

The Israeli military has known of the threat since at least 2001, when Hamas used a tunnel to detonate explosives under an Israeli border post. Since 2004, the Israeli military’s Samur, or “Weasels,” detachment has focused on locating and destroying tunnels, sometimes with remote-controlled robots. Those going inside carry oxygen, masks and other gear.

Israel has bombed from the air and used explosives on the ground to destroy tunnels in the past. But fully dislodging Hamas will require clearing those tunnels, where militants can pop up behind advancing Israeli troops.

During a 2014 war, Hamas militants killed at least 11 Israeli soldiers after infiltrating into Israel through tunnels. In another incident, an Israeli officer, Lt. Hadar Goldin, was dragged into a tunnel inside Gaza and killed. Hamas has been holding Goldin’s remains since then.

Ariel Bernstein, a former Israeli soldier who fought in that war, described urban combat in northern Gaza as a mix of “ambushes, traps, hideouts, snipers.”

He recalled the tunnels as having a disorienting, surreal effect, creating blind spots as Hamas fighters popped up out of nowhere to attack.

“It was like I was fighting ghosts,” he said. “You don’t see them.”

Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant on October 27 said he expected a difficult ground offensive, warning it “will take a long time” to dismantle Hamas’ vast network of tunnels. As part of the strategy, Israel has blocked all fuel shipments into Gaza since the war erupted. Gallant said that Hamas would confiscate fuel for generators that pump air into the tunnel network. “For air, they need oil. For oil, they need us,” he said.

The Israeli military also said on October 26 it had carried out “very meaningful” airstrikes on underground targets.

Typically, modern militaries have relied on punishing airstrikes to collapse tunnels. Israeli strikes in Gaza so far in this war have killed over 7,300 people, according Gaza’s Health Ministry. But those strikes can inflict only limited damage on the subterranean network.

U.S. forces fighting the Vietnam War struggled to clear the 120-kilometer (75-mile) network known as the Củ Chi tunnels, in which American soldiers faced tight corners, booby traps and sometimes pitch-dark conditions in the outskirts of what was then Saigon, South Vietnam. Even relentless B-52 bombing never destroyed the tunnels. Nor did Russian strikes on the Ukrainian steel mill in 2022.

Underlining how tough tunnels can be to destroy, America used a massive explosive against an Islamic State group tunnel system in Afghanistan in 2017 called “the mother of all bombs,” the largest non-nuclear weapon ever used in combat by the U.S. military.

AN ADDITIONAL LAYER OF COMPLEXITY

Yet in all those cases, advancing militaries did not face the challenge that Israel does now with Hamas’ tunnel system. The militant group holds some 200 hostages that it captured in the October 7 assault, which also killed more than 1,400 people.

Hamas’ release on October 23 of 85-year-old Yocheved Lifshitz confirmed suspicions that the militants had put hostages in the tunnels. Lifshitz described Hamas militants spiriting her into a tunnel system that she said “looked like a spider web.”

Clearing the tunnels with hostages trapped inside likely will be a “slow, methodical process,” with the Israelis relying on robots and other intelligence to map tunnels and their potential traps, according to the Soufan Center, a New York security think tank.

“Given the methodical planning involved in the attack, it seems likely that Hamas will have devoted significant time planning for the next phase, conducting extensive preparation of the battlefield in Gaza,” the Soufan Center wrote in a briefing. “The use of hostages as human shields will add an additional layer of complexity to the fight.”

The potential fighting facing Israeli soldiers also will be claustrophobic and terrifying. Many of the Israeli military’s technological advantages will collapse, giving militants the edge, warned Daphné Richemond-Barak, a professor at Israel’s Reichman University who wrote a book on underground warfare.

“When you enter a tunnel, it’s very narrow, and it’s dark and it’s moist, and you very quickly lose a sense of space and time,” Richemond-Barak told The Associated Press. “You have this fear of the unknown, who’s coming around the corner? … Is this going to be an ambush? Nobody can come and rescue you. You can barely communicate with the outside world, with your unit.”

The battlefield could force the Israeli military into firefights in which hostages may be accidentally killed. Explosive traps also could detonate, burying alive both soldiers and the hostages, Richemond-Barak said.

Even with those risks, she said the tunnels must be destroyed for Israel to achieve its military objectives.

“There’s a job that needs to get done and it will be done now,” she said.