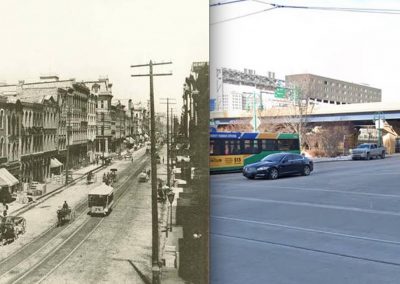

Before the freeways came in, Bronzeville, on Milwaukee’s North Side, was a vibrant neighborhood known for its restaurants, bars and jazz scene. The area had been home to successive waves of immigrants and most recently had become the heart of the city’s Black community.

But it suffered a major blow in the 1960s when large swaths of the neighborhood were razed to make way for elevated freeways, part of a nationwide highway construction boom.

The new highways spurred a mass exodus of white residents to the suburbs — at the expense of Black communities like Bronzeville. “It became more important to move [commuters] smoothly from their [suburban] homes to downtown,” said Clayborn Benson, the founder and executive director of the Wisconsin Black Historical Society/ Museum. “That was the ultimate goal.”

Families and businesses in areas like Bronzeville were displaced, and the ripple effects are still being felt today, Benson said.

“Eventually, those neighborhoods became economically deprived,” he said. “You can still see that today, just like you can see economic development in certain areas of the city and not others.” Today, Milwaukee is one of the most segregated cities in the United States.

For the residents whose homes were spared but now bordered highways, their reward was an increased exposure to pollutants, higher asthma rates and other health problems such as cardiovascular disease.

But today, cities across the country are reconsidering the highways stretching through their communities, and some are pushing for them to be torn down altogether.

In downtown Milwaukee, about five miles south of Bronzeville, Rethink I-794 is advocating for replacing Interstate 794’s overpass with a pedestrian-friendly boulevard linking the city center with the trendy Third Ward district and the waterfront.

“There’d be more room for walking and biking, and it would strengthen the tax base in Milwaukee,” said Gregg May, who leads the Rethink I-794 initiative.

Activists have been pushing for I-794’s removal for decades. Now billions of dollars from President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act and Infrastructure Bill may transform major projects from pie-in-the-sky aspirations to shovel-ready realities.

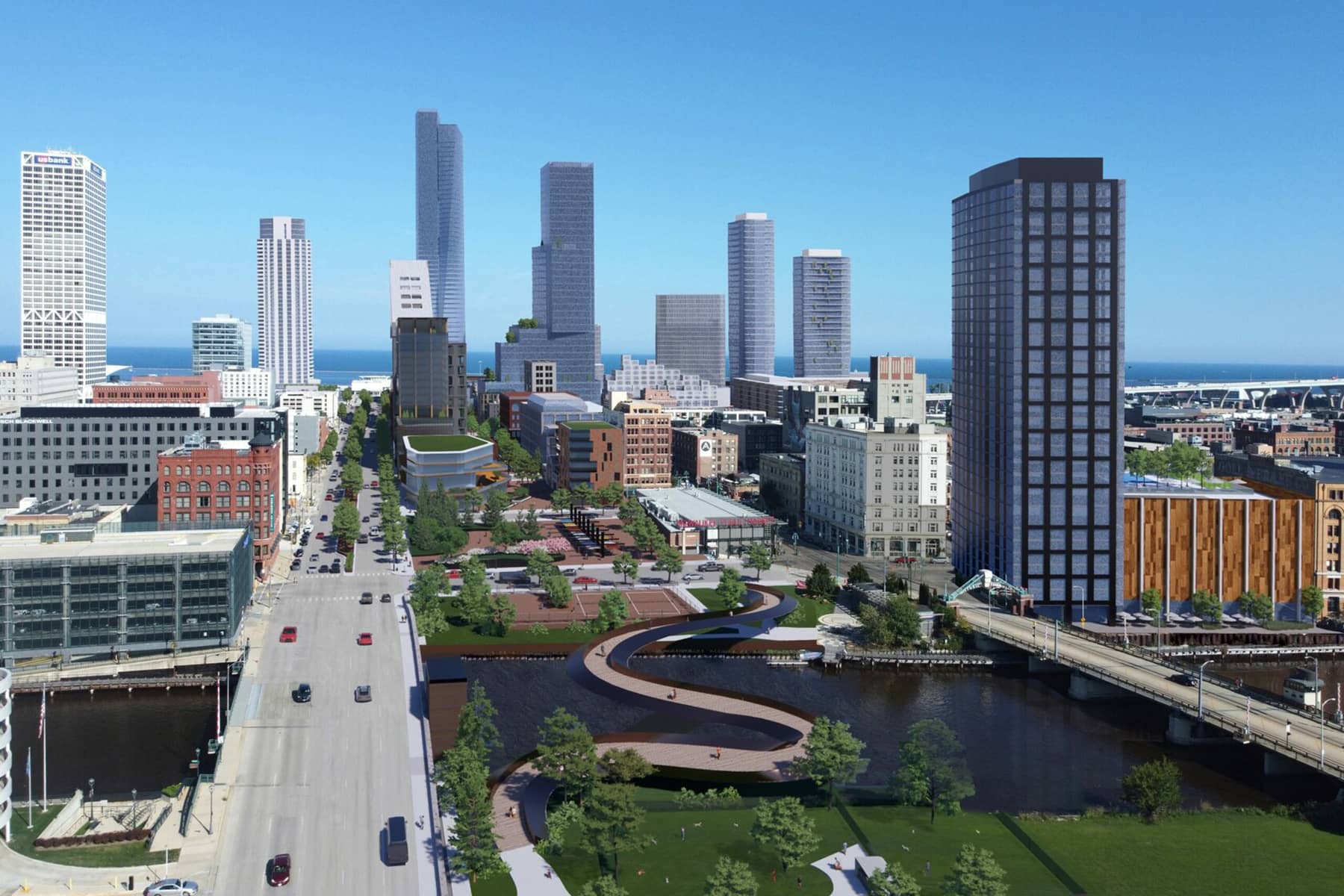

Advocates like May often reference the Park East teardown nearby, which started over 20 years ago, as an example of what is possible when pedestrian-centered design replaces highways.

The Park East removal, less than two miles north of the proposed I-794 project, opened up 24 acres of land in downtown Milwaukee and helped propel an era of urban highway removal nationwide.

The project created an opportunity for cities to think more strategically about how highways serve a given area and whether it still aligns with current needs, explained Ruth Steiner, director of the Center for Built Environment at the University of Florida.

“Rebuilding or repairing what’s there may not be the optimal solution,” she said, adding that many historic freeway projects have become obsolete or are in need of major overhauls.

The area near Park East has seen increased property values and created more space for pedestrians and recreation. Moreover, its rebirth as a lower-capacity boulevard has decreased emissions from the thousands of vehicles that once passed overhead daily.

The removal allowed developers to build the Fiserv Forum, the home court of the Milwaukee Bucks, and the adjoining Deer District, a mix of indoor and outdoor entertainment and community spaces. It also spurred revitalization in the nearby Brewery District, which for more than a century churned out cans of Pabst Blue Ribbon, bringing in new mixed-use developments, parks and co-working spaces.

“One hundred percent we looked at Park East and what happened there as an example of what could happen again,” said May. “They said it would ruin traffic flow, but none of that really happened and people now see the benefits of having it removed.”

Steve Morales, a partner at Rinka Architects who helped to develop the Deer District, said the Park East teardown opened up opportunities for development that are still coming to fruition.

“There’s really still more to do, but we have already made some really great possibilities come true,” he says. The development centers around a public plaza that hosts fitness classes, a marketplace and small fairs and festivals. “We all envisioned the Deer District as a way to give people from all walks of life and from different communities a place to call their own,” Morales says.

While the teardown of the Park East freeway was supported by local and state funds, its main investment came through an influx of federal money. Over the last several decades, a series of legislative acts and initiatives have provided local entities more power to design, and in some cases remove, highways and other roadways.

But all of these funding sources are dwarfed by the federal government’s latest initiative to address inequities and meet President Biden’s climate goals, the Inflation Reduction Act, which earmarks $3 billion for improving roads and “removing, replacing, or retrofitting highways and freeways to improve connectivity in communities” through Neighborhood Access and Equity Grants. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, passed in 2021, also set aside $1 billion for the US Department of Transportation’s Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program.

Steiner, a Wisconsin native who said the Park East freeway helped spur her interest in urban planning, said that the infrastructure funding has given cities more opportunities to align transportation with the needs of residents and neighborhoods.

“Are [the freeways] dividing people or can it be redesigned to slow down traffic to allow people to have access to places where they want to go?” she said. “Transportation facilities are necessary, but how do you fit the great roadways into the other activities they are engaging in the city.”

The fate of I-794 is far from settled and many states continue to invest in highways over public transportation. The Wisconsin Department of Transportation has proposed to rebuild I-794 at a cost of $300 million. Meanwhile, officials have announced plans to widen a 3.5-mile section of freeway nearby in an attempt to ease congestion (studies have shown that increasing road capacity does not improve traffic congestion in the long term). That plan has also netted criticism, including the social justice coalition Milwaukee Inner-City Congregations Allied for Hope.

Peter Park, Milwaukee’s former planning director and a longtime proponent of tearing down I-794, said the Inflation Reduction Act, and other available federal funds, present an opportunity for cities, including Milwaukee, to move further away from a polluting and costly highway system that burdens local, state, and federal systems, towards a healthier and more economically sustainable approach.

“It’s the difference between spending public money on things that cost more to maintain in the future and realizing that those things are not necessary anymore,” said Park. “We need to think about the long-term benefits rather than the short-term inconvenience of traffic congestion.”

Park, now an adjunct professor at the University of Colorado Denver, describes highways as a failed public experiment. While it’s hard for most to envision life without them, he said cities are better off without them.

“There’s not a neighborhood that got improved or better when a freeway went through it,” he said. “Every single time that we take a freeway out of the city, whether in Seoul, Korea, or the West Side Highway in New York or Park East in Milwaukee, things get better and the world didn’t end.”

This article is co-published with Reasons to Be Cheerful as part of the New Climate Economy series. Nexus Media News is an editorially independent, nonprofit news service covering climate change. Follow us @NexusMediaNews.

Edgar Mendez

Rethink I-794

Originally released on Nexus Media News as Freeways Blighted Milwaukee’s North Side. Can Tearing Them Down Bring New Life to the City?, and republished under the terms of a Creative Commons’ Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license CC BY-ND 3.0.