Since the murder of Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida during Black History Month in 2012, America has been on edge. The senseless killing and subsequent acquittal of his murderer, outraged the Black community.

“You know, when Trayvon Martin was first shot I said that this could have been my son. Another way of saying that is Trayvon Martin could have been me 35 years ago. And when you think about why, in the African American community at least, there’s a lot of pain around what happened here, I think it’s important to recognize that the African American community is looking at this issue through a set of experiences and a history that doesn’t go away…The African American community is also knowledgeable that there is a history of racial disparities in the application of our criminal laws — everything from the death penalty to enforcement of our drug laws. And that ends up having an impact in terms of how people interpret the case.” – President Barack Obama, July 19, 2013

On the day that George Zimmerman was acquitted for the murder of Trayvon Martin, Alicia Garza went on Facebook and posted this: “I continue to be surprised at how little Black lives matter… Our lives matter.” Her friend Patrice Cullors, who was also outraged by the verdict, added a hashtag in her response to Garza’s post and #BlackLivesMatter became a thing. Along with their friend Opal Tometi they created what became the Black Lives Matter Movement.

In August 2014, an unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown, was shot to death by a White police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. This led to days of unrest around the country and the slogan Black Lives Matter became a part of the American lexicon. Similar deaths before and after Martin and Brown became part of the narrative describing the fact that Black lives are just as valuable as any others. Many Whites responded, naively and insensitively that “all lives matter.” If all lives really mattered, that would include Black lives.

We know from experience that this is not true. That is not to say that Black lives don’t matter, instead it means that it does not appear from the way Black people have been treated for the last four hundred and three years that their lives have mattered. Their bodies and labor have certainly mattered. But their lives have been lived in a place that evidently provided a different standard of value than that given to people referred to as White Americans.

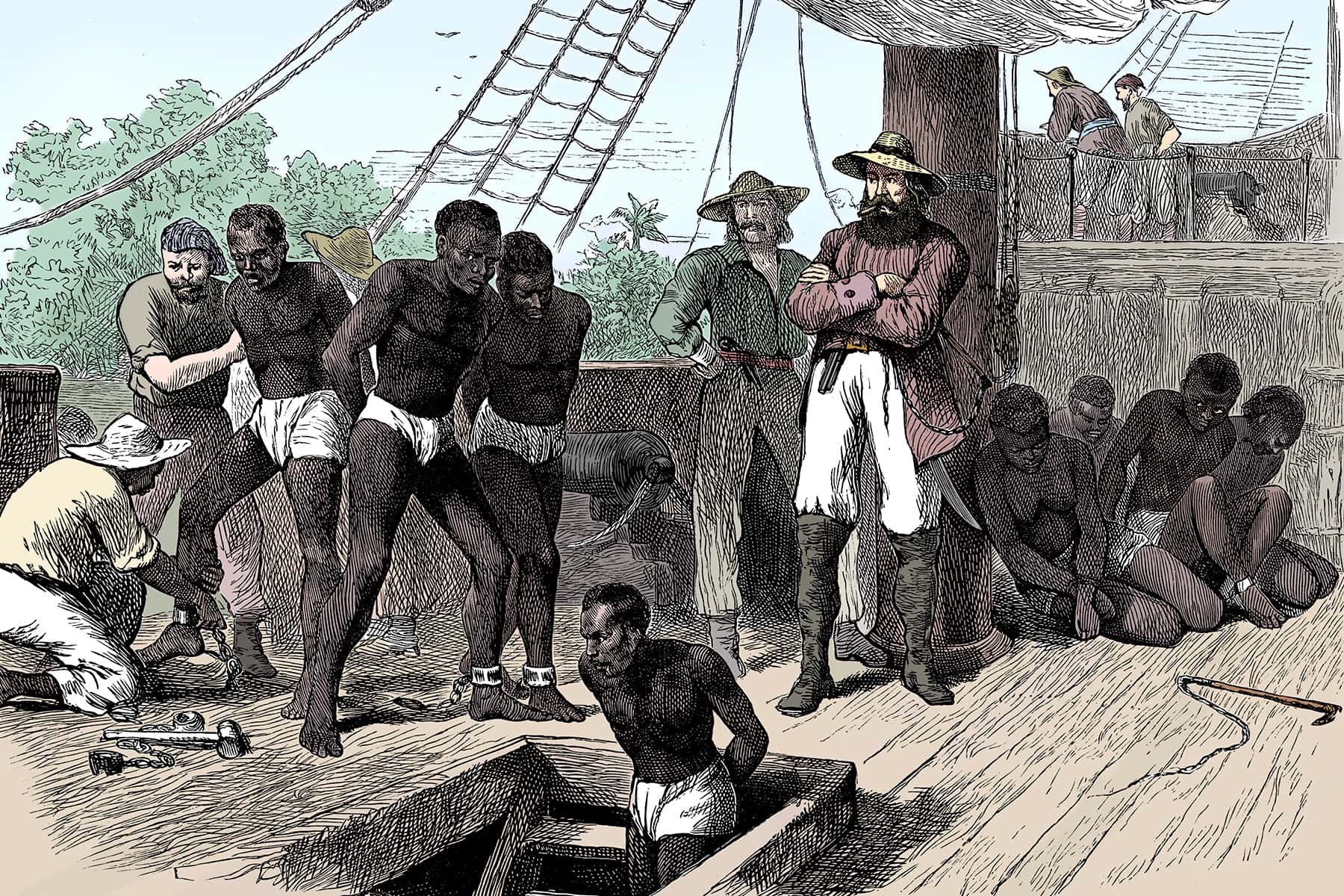

I wanted to contribute historical context to the idea of Black Lives Matter. There is extensive evidence showing that Black people’s lives have not mattered in America. This has been the case since the first kidnapped Africans arrived in 1619.

Knowing that for two hundred forty-six years Blacks were enslaved cannot explain and quantify the lived experience of kidnapped Africans and their generations of kinfolk. That horrible experience has never been told in its entirety, particularly how it helped to build the wealth of the United States. This wealth would be mostly out of reach for those considered black for generations. Historian Edward E. Baptist in his book, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism, said it best.

“The idea that the commodification and suffering and forced labor of African Americans is what made the United States powerful and rich is not an idea that people necessarily are happy to hear. Yet it is the truth.”

The offspring of the enslaved Africans have continued to be treated differently than any other group. The condition of the Black community in 2022 is connected directly to our beginnings in this country. Although people like to say, “that was a long time ago” it really was not. America is a young nation. The last of the enslaved Africans had children who just died in the last few decades.

Through generations, Americans passed down their own very specific ways of talking about and treating Black people. Those views are still alive and well today. The mindset of those who wrote the first formal slave law in Massachusetts included seeing Black people as an inferior group, not deserving of equal treatment. Over the course of many years, laws were passed in all of the original thirteen colonies which formalized the legal enslavement of Black people. Even before the slave laws made it explicitly clear that Blacks were going to be enslaved, we must remember that practically every African coming to this country came across the Atlantic on slaving ships whether their condition after arriving was as a lifelong slave or not.

Slavery was not the end of the devaluation of Blacks. The value White society placed on Black bodies did not match the value Black people have seen in themselves. On her 2017 book, The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, From Womb to Grave, In the Building of a Nation, Diana Ramey Berry clearly asserts this point.

“Historically, black bodies in the United States have represented two competing values: one ascribed to the internal self and the other the external body. White valuation of the black body under slavery is one of the most dramatic examples of the latter. An enslaved person had individual qualities that enslavers evaluated, appraised, and ultimately commodified through sale. Yet enslaved people had a different conception of their value…”

Years after their legal enslavement by the millions ended, Whites across the country debated the future and value of Black people in America. There were plans by both Lincoln and Jefferson to colonize freed Blacks outside the country.

George Washington Williams wrote in, History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880 (Vol. 2) in 1883 that the earliest members of the American Colonization Society proposed colonization of free Blacks because, “this was the only hope of the free Negro; that the proscription everywhere directed against his social and intellectual endeavors cramped and lamed him in the race of life…”

Lincoln later asserted a similar point when speaking to a group of Black leaders he invited to the White House in 1862.

“You and we are different races. We have between us a broader difference than exists between almost any other two races. Whether it is right or wrong I need not discuss, but this physical difference is a great disadvantage to us both, as I think your race suffer very greatly, many of them by living among us, while ours suffer from your presence. In a word we suffer on each side. If this is admitted, it affords a reason at least why we should be separated.”

Contrary to what most of us learned in history class about the period known as Reconstruction, it was one of the bloodiest periods in American history. The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as the Freedmen’s Bureau kept detailed records of the beatings, rapes, and murders Blacks suffered after they gained their “freedom.” The new governments set up during Reconstruction passed the amendments which ended slavery, gave Blacks citizenship and Black men the right to vote.

This did not protect them from the incredible violence of the people who had formerly kept them in shackles.

“I have classified these outrages as follows: Twenty-three cases of severs and inhuman beating and whipping of men; four of beating and shooting; two of robbing and shooting; three of robbing; five men shot and killed; two shot and wounded; four beaten to death one beaten and roasted; three women assaulted and ravished; four women beaten; two women tied up and and whipped until insensible; two men and their families beaten and driven from their homes, and their property destroyed; two instances of burning of dwellings, and of one inmate shot.” – Report by Freedmen’s Bureau official in Kentucky

Historian Leon Litwack in his book, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery, wrote about the change in the value of Black bodies after the Civil War ended.

“Before the war, a Tennessee farmer explained, the slave ‘was so much property. It was as if you should kill or maim my horse. But now the nigger has no protection.’”

This lack of protection would play out over several decades with Blacks being lynched across the country and dozens of anti-black race riots being carried out by Whites across the country. I will discuss the details of those in a later piece in this series.

Physical violence would only be a small part of the devaluation of Black lives moving into the twentieth century. Legalized segregation, known as Jim Crow laws would help to marginalize the lives of Black people even one hundred years after Lincoln’s famous Emancipation Proclamation supposedly gave them freedom.

The years after the Civil Rights Movement was supposed to be a “post-racial” America. It was not. Racism was and is alive and well.

It is hard to understand the psychological trauma suffered by Black people over dozens of generations. Imagine being kidnapped from the place of your birth, placed in shackles and transported across the Atlantic Ocean in the most horrific conditions imaginable. Upon your arrival in a strange new land, you soon discover that you will be enslaved along with your family until the day that you die. You will be forcibly separated from your friends and family at the whim of any given White person. You will watch your wife, sister and mother be raped right in front of you, knowing that you can do nothing about it because White people appear to have all the guns in the world.

Dr. Joy DeGruy wrote about this generational trauma in, Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing. The book is described as:

“Dr. DeGruy first exposes the reader to the conditions that led to the Atlantic slave trade and allowed the pursuant racism and efforts at repression to continue through present day. She then looks at the seemingly insurmountable obstacles that African Americans faced as the result of the slave trade. Next she discusses the adaptive behaviors they developed — both positive and negative — that allowed them to survive and often even thrive. Dr. DeGruy concludes by reevaluating those adaptive behaviors that have been passed down through generations and where appropriate. She explores replacing behaviors which are today maladaptive with ones that will promote, and sustain the healing and ensure the advancement of African American culture.”

If you closely study the way Black people interact with one another today it is clear to see that for some, Black lives don’t matter. We see nearly daily across the country the impact of the devaluation of Black lives manifest itself in self-destructive behavior that is a way to cope with the low self-esteem which some have internalized. I will discuss this in more detail in the article which looks at devaluation in Science and Medicine.

This is just small part of the story of how Black lives have been devalued in America. I will explore this devaluation in laws and politics, our so-called justice system, education and culture. I’m constantly learning more, and re-educating myself. The journey is never ending. It is my hope that this series will enlighten those who have been in the dark about how the lives of Black people have been devalued in this country.

This is the first step for many in trying to understand the current state of the Black community. It should not be the last. You will clearly see the tremendous strength and resiliency that has been on display and passed down by generations of Africans in America as we have survived in a land and among a people who have continued to devalue us.

Our stories matter. Our lives matter. When will America and Americans acknowledge this?

- Do Black Lives Matter? Part 1: An introduction to the historical devaluation of Black people

- Do Black Lives Matter? Part 2: The devaluation of Black people in politics and law

- Do Black Lives Matter? Part 3: The devaluation of Black people in the criminal justice system

- Do Black Lives Matter? Part 4: The devaluation of Black people in science and medicine