There are an estimated 4 million military-connected children in the United States. With the longest war in American history finally over, these kids have been affected by war like no previous generation, especially in families where the veteran has PTSD.

The Veterans Administration reported that 21 percent of post-9/11 troops who sought help at the VA from 2004 to 2009 had PTSD, 2 percent had traumatic brain injury and 5 percent had both. Now that these veterans are home, their lives – and the lives of their families – are forever changed as young children face the stress of living with someone who, in many ways, is a new and sometimes unpredictable parent. Some call this secondary PTSD.

A ‘contagious disease’

“The children have this expectation, this vision of ‘Oh, daddy’s coming home. This is going to be great,’ and they have these memories, perhaps if they’re older, of the fun they used to have with daddy,” said psychologist Bob Motta. “But the person coming back is a somber, negative, machine-like being. That shock of your expectation compared to what comes back is really tough to take.”

Motta was drafted into the Army during the Vietnam War, serving in the 1st Calvary Division, often working in helicopters as a door gunner or helping deliver medical supplies. When he came home, he decided to study how PTSD affected the families of Vietnam vets.

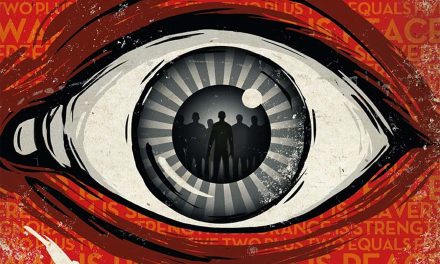

“The original medical conceptualization of PTSD is that it is a disorder of an individual but what research has consistently shown is that’s not true,” he said. “It’s a disorder that spreads to others particularly those who have close and extended contact to the person just like the flu would. It’s a contagious disease.”

That disease can spread not only to a caring spouse, but to children as well. Motta calls this secondary trauma. People who have PTSD often “re-experience” traumatic events through memories or dreams. This can happen quickly and can seem to come out of nowhere. These symptoms often come with strong feelings of grief, guilt, fear, or anger.

Sometimes the experience can be so strong that it feels like the trauma is happening again. These symptoms can be scary not only for individuals but also for their children. Children may not understand what is happening or why it is happening. They may worry about their parent or worry that the parent cannot take care of them.

Multiple studies in different countries have shown that kids are affected by having a parent who is a combat veteran with PTSD. For example, a 2008 Bosnia and Herzegovina study on kids of veterans with PTSD found that the father’s PTSD may have “long-term and long-lasting consequences on the child’s personality.”

Many children may develop symptoms that mirror those of their injured parent. An example might be a young child having nightmares because of their parent’s nightmares or because they are worrying about their parent’s behavior. A child may have trouble paying attention at school or exhibit new behavioral problems because he or she is thinking about her parent’s problems. This impact on a child due to their worry and identification with their injured parent is sometimes referred to as “secondary traumatization.”

A child’s symptoms can get worse if there is not a parent who can acknowledge the effects of the parental injury and communicate with their children to help them feel better. Usually, children are spontaneously happy and enjoy playing and having a good time, but traumatized children show radically different behavior.

“They’re somber. They’re moody. They’re withdrawn. They’re irritable. If they were functioning OK in school, their grades have now fallen off,” Motta said. “They can’t focus. Their memory is very poor. And it’s because they’re so absorbed with the problems of their parent that they can’t really focus well in school.”

David Martin and Sheila MacVicar

The original unedited version of this article was published as PTSD’s ‘secondary’ victims: the children of veterans