This special series by Reggie Jackson explores his journey across four cities in Alabama, to visit historical sites that many are trying to erase from public memory so the disturbing truth about racism, segregation, and White Supremacy can be forgotten. mkeind.com/alabamajourney

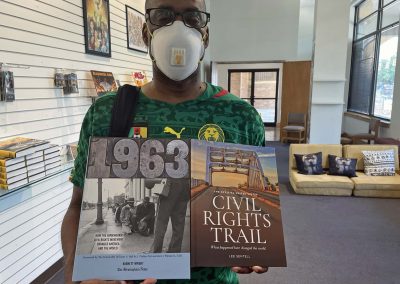

This is most unusual way that I have produced a column. I will write part of it before I begin my journey “down South” and the remainder as I explore, Birmingham, Selma, and Montgomery, Alabama. As I get ready to embark on a journey along part of the National Civil Rights Trail certain things stand out in my mind. The articles will be written as a series covering the places my wife and I visited on the trip.

I will traverse the hundreds of miles between Milwaukee and the Deep South on a trip to honor the memory of those who preceded me in battle. This fight to be treated like human beings in a nation that has often proclaimed it treats us all that way, but offers an abundance of evidence that it has not done so for those from Africa, is part of how I honor my ancestors.

I’ve chosen to go to the places in America where Black people challenged this country to live up to the ideals of the Founding Fathers. America has still not lived up to those lofty standards. These cities offer evidence of just how difficult this struggle has been. They also give us insight into the resilience and constant fight for human rights Africans in America have displayed for over four hundred years.

What’s so ironic about this journey, is that many people are fighting hard to convince me that the events which put these cities on the world map in the 1950s and 60s, did not happen. These people, who are telling us out loud that our truth is a lie, are the descendants of the people they want us to forget. They are ashamed of their ancestors. They want to pretend that systems of racial dominance built by their ancestors don’t exist. Unfortunately for them, their ancestors left evidence behind because they had no shame.

Those who have turned the word truth into a word with little real meaning today, are winning the hearts and minds of many of uncomfortable Americans. Far too many people in this country believe things that are called lies today that were absolutely acknowledged as truths when they happened. America as a nation has a very ugly history that has been hidden from most of us by an education system that is embedded with racism.

When history class feels like “his-story” class we all lose. “His-story” is the story of Whites in America. It does not value the billions of people of color that have lived on this stolen land we call America. “His-story” leaves the ugly memories out. “His-story” paints a picture that is a distortion of epic proportions. “His-story” tells us to pretend the words of Thomas Jefferson were not written without hypocrisy. Jefferson knew clearly that when he said “all men are created equal” he did not really mean all of us. The historical record is clear on this. How else can you explain his purchasing of and so-called ownership of hundreds of Africans?

This bitter truth is a hard pill to swallow when you’ve been told the exact opposite your entire life. We’ve been taught in such a way that we are not allowed to question the past. Why is it that few of us in history class ever raised our hands and questioned the fact that dozens of the White men called Founding Fathers were slaveholders, when it was pretty obvious? Why did our teachers refuse to engage us in conversations about the obvious contradiction in what the founders said versus what they did?

Why were we never taught to critically think about what we learned in social studies class? Why were we treated as empty vessels that teachers poured information into? Why did we receive better grades for regurgitating the information we received rather than if we somehow challenged it? Why did I learn as a child that people like me never contributed anything positive to this nation until Dr. King, Rosa Parks and others fought for “civil rights?”

I embark on a trip that will surely encompass a roller coaster of emotions. I’ve visited Birmingham before, back in 2008. I took a trip that year, the fortieth anniversary of Dr. King’s assassination. I visited Birmingham and Memphis on that trip. I was in Memphis at the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel where Dr. King was murdered, exactly forty years earlier. I saw many friends and compatriots of Dr. King that day. I met Jesse Jackson for the first time ever. I spoke briefly with the late Joseph Lowery and John McCain on that day. It was an amazing day.

Birmingham’s 16th St. Baptist Church, the scene of the murder of four Black girls just weeks after the March on Washington was one of the main things I planned to visit on that trip. The memorial for those precious children was closed the day I arrived in Birmingham. On this upcoming trip I will have the honor of paying my respects to them properly.

In Selma I will walk across the infamous Edmund Pettus bridge and visit the National Voting Rights Museum.

The place I most anticipate visiting is Montgomery. I will spend time at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum created by Bryan Stephenson. I met Mr. Stephenson years ago when he spoke in Wisconsin. I chatted with him and told him how much I admired his work. His book, Just Mercy, is one of the most impactful books I’ve ever read. I wrote him a thank you letter after reading it. I mentioned my connection to Dr. James Cameron, founder of America’s Black Holocaust Museum. He told me that he had met Mr. Cameron on several occasions. I realized later that Mr. Cameron’s survival of one of the most infamous lynchings in the country’s history influenced Stephenson’s creation of the The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a memorial to thousands of lynching victims.

I know that the current battles to discuss American history in a more honest way will color my emotions on this upcoming trip. It will be difficult to forget that the historical places I see and the events in those places years ago feel like a threat to a segment of our society. There is a group that is pushing to erase this history in the few places it is taught. Our schools still do a poor job of teaching this history in detail. Despite this, dishonorable people want us to ignore this history. I will never give up in my efforts to do the exact opposite.

I will chronicle the trip in the next section of this article.

My wife and I embarked on a journey that took about 2,000 miles to complete. We left Milwaukee two days after our daughter was married. This trip was a journey that I had planned months ago. I knew where I wanted to go and what I wanted to see but I saw and experienced much more than I anticipated.

As we arrived in Birmingham our first visit would be the 16th St. Baptist Church. The church was first organized in 1873 and is the oldest Black church in Birmingham. The beautiful, majestic brick building the leaders of the church built in 1884 was more grand than any White church in town. Because the leaders the church appeared to not be in alignment with the social order of the day, the city leaders forced them to tear the building down. They were not deterred. They came back in the early 1900s and built the current sanctuary on a budget of $26,000 raised by the parishioners.

Wallace Rayfield, the state’s only Black architect and T.C. Windham, a black contractor from Birmingham completed the church in 1911. The website tells us this about the church:

“The present church was completed in 1911. Of modified Romanesque and Byzantine design, it features twin towers with pointed domes, a cupola over the sanctuary accessible by a wide stairway, and large basement auditorium with several rooms along the east and west sides. Because of segregation, the church, and other black churches in Birmingham, served many purposes. It functioned as a meeting place, social center and lecture hall for a variety of activities important to the lives of the city’s black citizens. W.E.B. DuBois, Mary McLeod Bethune, Paul Robeson, and Ralph Bunche were among many noted black Americans who spoke at the church during its early years. African Americans from across the city and neighboring towns came to Sixteenth Street, then called “everybody’s church,” to take part in the special programs it hosted. Due to Sixteenth Street’s prominence in the black community, and its central location to downtown Birmingham, the church served as headquarters for the civil rights mass meetings and rallies in the early 1960’s. During this time of trial, turmoil and confrontation, the church provided strength and safety for black men, women and children dedicated to breaking the bonds of segregation in Birmingham, a city that black citizens believed to be the most racist in America.”

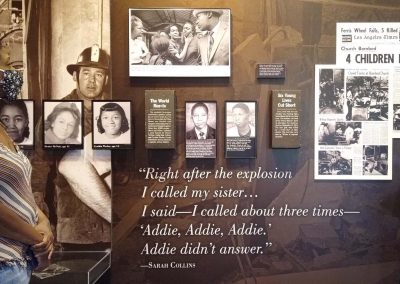

Of course the church is most known for the cowardly and despicable bombing that killed 14-year-olds Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and 11-year-old Cynthia Wesley on September 15, 1962 at 10:22 a.m. Susan Collins, Addie Mae’s sister was badly injured and temporarily blinded by the bombing. She lost her right eye as a result of the blast that she survived. Susan is now 93-years-old and an overlooked victim of the bombing. Unbeknownst to us, she spoke to visitors at the church one day before we arrived. It would have been great to meet her and hear her speak about that day in person.

Twenty-six children were in the church preparing for Sunday services when the bomb exploded. A box of dynamite had been planted near the basement and was set to go off that morning. Sixteen people walking past the church at that moment were also injured.

Dr. King eulogized the four girls by saying “This afternoon, we gather in the quiet of this sanctuary to pay our last tribute of respect to these beautiful children of God. Now the curtain falls. They move through the exit. The drama of their earthly life comes to a close. These children, unoffending, innocent, and beautiful.”

As is so often the case, a place of strategic importance during the Civil Rights Movement had been targeted by White bigots. The church was the staging ground for the campaign by Birminghams Black community to challenge segregation. The city was the site of so many bombings over the years that it was known by the Black community as “Bombingham.” The Ku Klux Klan used that tactic to intimidate the Black community for years.

The four suspects, Robert E. Chambliss, Bobby Frank Cherry, Herman Frank Cash, and Thomas E. Blanton, Jr., all KKK members faced no state or federal charges in the aftermath of the bombing and murder of the four children. It would not be until 1977 before Alabama Attorney General Robert Baxley reopened the case.

Chambliss was known in Birmingham as ”Dynamite Bob” for his links to many of the more than 40 blasts that terrorized the city’s Black citizens over many years. According to the Daily Beast, Chambliss, was convicted, “in part on the testimony of his own niece who had heard him boast on the eve of the bombing that after the next day the blacks would end their campaign to integrate the city’s schools. When Chambliss’ wife Flora (who had also provided information about her husband’s activities to the authorities) learned of the verdict, she was heard to yell, ‘Hallelujah!’” Chambliss received a sentence of life for the murders. He died in prison in 1985.

Seventeen years after the bombing, Blanton and Cherry were indicted in May 2000. Both terrorists were convicted at trial and sentenced to life in prison. During Blanton’s trial a secretly recorded audiotape produced by the FBI showed him telling his wife that he had gone down to a meeting under the Cahaba River bridge to in his words “plan the bomb.”

A little known element of this case is that back in 1965 according to the NY Times, “An FBI agent who found witnesses placing the suspects at the bombing scene sought permission to brief the local U.S. attorney and state prosecutor.” FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover killed the investigation claiming the chances for success were “very remote.” He also claimed the secretly recorded tape was “illegal” and would not be admissible in court. As a result decades passed before these men saw justice.

Herman Frank Cash, had died in 1994 and was never formally charged.

Another important part missing from the narrative of the horrific events of that day in Birmingham, was the murders of two Black teenage boys killed by Whites on the same day as the bomb went off.

“Later that same day, unknown to many people, two African-American boys were killed in separate incidents.”

– Andrea Taylor, President and CEO of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, interview with WBRC News in Birmingham in 2019.

13-year-old Virgil Ware was shot and killed by a 16-year-old White kid named Larry Sims, while he rode on the handlebars of his brother’s bike. He was shot and killed in cold blood just hours after the bombing at 16th St. Baptist Church. Sims served only six months in a juvenile detention center for the murder.

Later the same day, 16-year-old Johnnie Robinson was shot in the back with a shotgun and killed by Birmingham police officer Jack Parker who fired at a crowd of Black boys. The boys had thrown rocks at a group of White teenagers who rode by in cars chanting “two, four, six, eight, we don’t want to integrate” shortly after the bombing. It would not be until 2009 before Robinson’s family was contacted by the FBI and given the details of his murder.

As my wife and I spent time in the church, we saw and heard the tragic story that put to shame the myth of the March on Washington changing America. Despite the historic nature of that day, these girls were killed just over two weeks later.

It’s difficult to put into words how I felt emotionally while seeing the memorial to those four precious children. I knew I wanted to be in that space but nothing prepared me for the emotions of seeing the images of the damage caused by the dynamite or hearing the horrific aftermath as people pulled the girls bodies out of the rubble. Cynthia Wesley was decapitated by the bomb blast. The type of hatred that makes people want to plant a bomb in a church and kill children is a part of the heritage of the South. Defenders of the Confederacy and Jim Crow South still claim today that hate was not part of their legacy. They should be embarrassed to speak of their so-called heritage in a positive way.

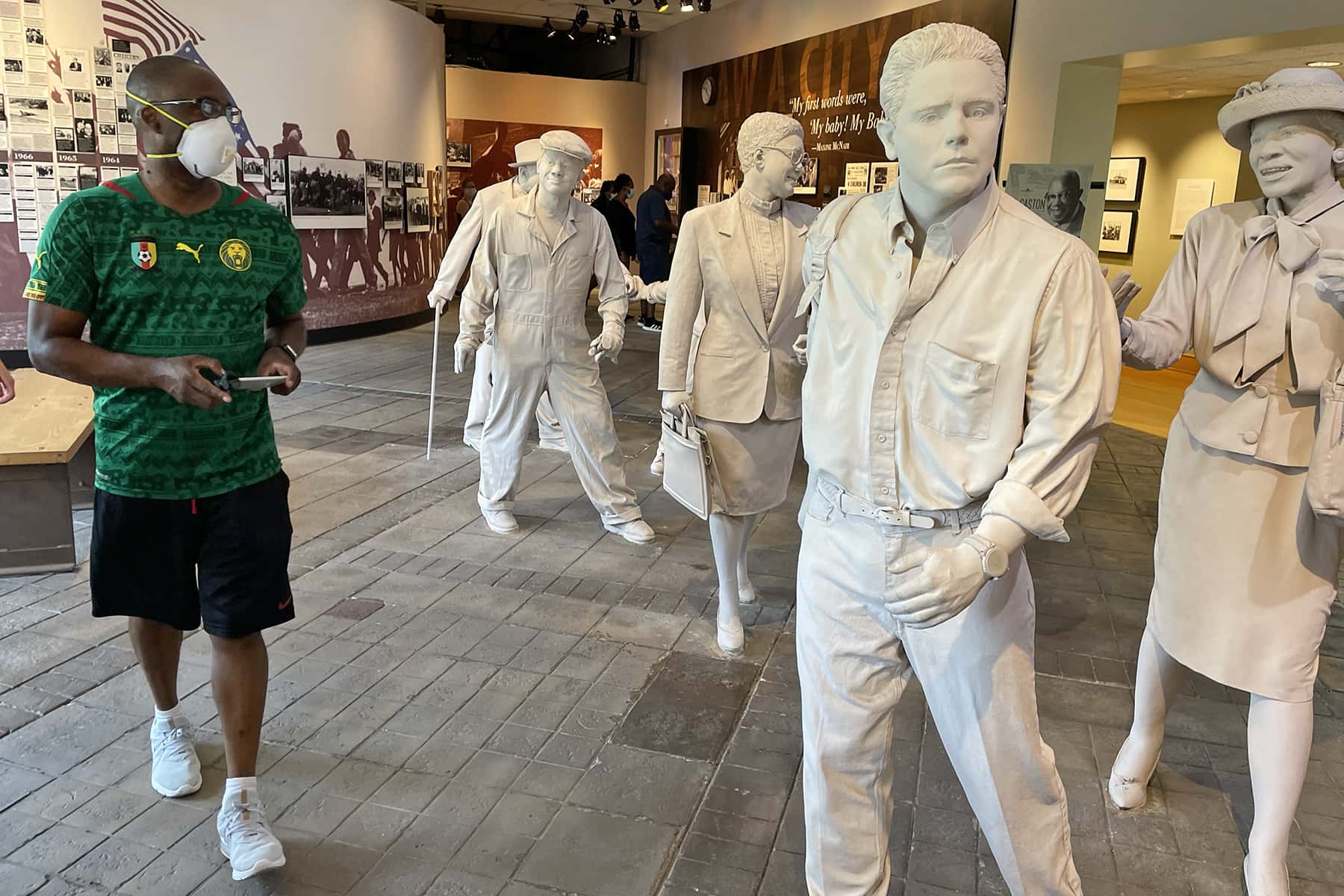

The church sits kitty corner from Kelly Ingram Park, the scene of police dogs and firehoses being sprayed on the children of Birmingham in the summer of 1963. Sculptures in the park depict the scenes from that campaign led by Dr. King to end segregation in what he called “America’s most segregated city.”

I have seen videos of the scenes that summer multiple times. Those do no justice to the fact that the firehoses were strong enough to tear bark off of trees. The sculptures in the park represent the strength of those Black children who came out in force when their parents mostly refused to do so out of fear of losing their jobs. When we teach the Civil Rights Movement history in schools we need to honor the role of young Black girls and boys who risked their lives to fight for their human rights.

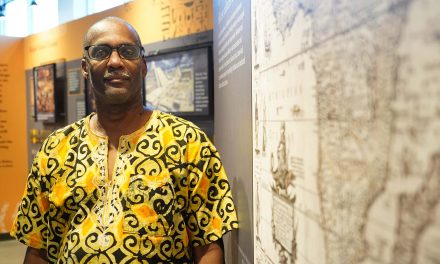

The last place we visited was the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, directly across the street from Kelly Ingram Park and the 16th St. Baptist Church. I had visited this museum in 2008. It was significantly different this time. Back during my first visit a large part of the museum was dedicated to the history of Birmingham.

The museum now focuses on the important role Birmingham played in the Civil Rights Movement before and after the campaign Dr. King led. We were able to see what’s called the Confrontation Gallery, which took us through a journey of the fight Blacks led under a great deal of resistance, much of it violent. We saw a fully dressed Ku Klux Klan member standing in front of a cross, a symbol of their racial terror campaigns.

We saw a “white” and “colored” water fountain, as well as multiple Jim Crow signs in the Barriers Gallery. A replica of one of the Freedom Riders buses as well as a replica of Dr. King’s cell in the Birmingham jail where he wrote his important Letter From a Birmingham Jail, that summer. While leaving the museum my wife and I met a young man who was at the museum with his daughter. The two of them were from Huntsville, Alabama. This was his oldest daughter and he was traveling with her along a similar sojourn through this history as we were. Little did we know at the time that we would run into them later in Montgomery at the exact spot where Rosa Parks was arrested.

Birmingham’s history is fraught with tragedies and triumphs, punches and counterpunches in the fight for dignity and human rights. The sacrifices made by members of that community when bombs were going off almost weekly, is a testament to the strength and resilience of Black people. They showed us the power of never giving up. They also showed us how to defeat bullies in police uniforms including the infamous Birmingham Police Commissioner Bull Connor.

Birmingham’s lasting memory to me will be the fact that despite the campaign that summer and the March on Washington, hatred had a home in America. Hatred against Black people was on full display. Decades passed before justice for those four girls happened. It showed me clearly that those two Black boys were martyrs but their families never had justice. Birmingham in many ways is a microcosm of America’s ugly racial history.

Our next stop would be Selma and the infamous Edmund Pettus bridge. I’ll discuss that in tomorrow’s column.

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Birmingham, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Selma, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Montgomery, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Tuskegee, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: Final thoughts on my journey to visit Alabama and the history some want us all to forget