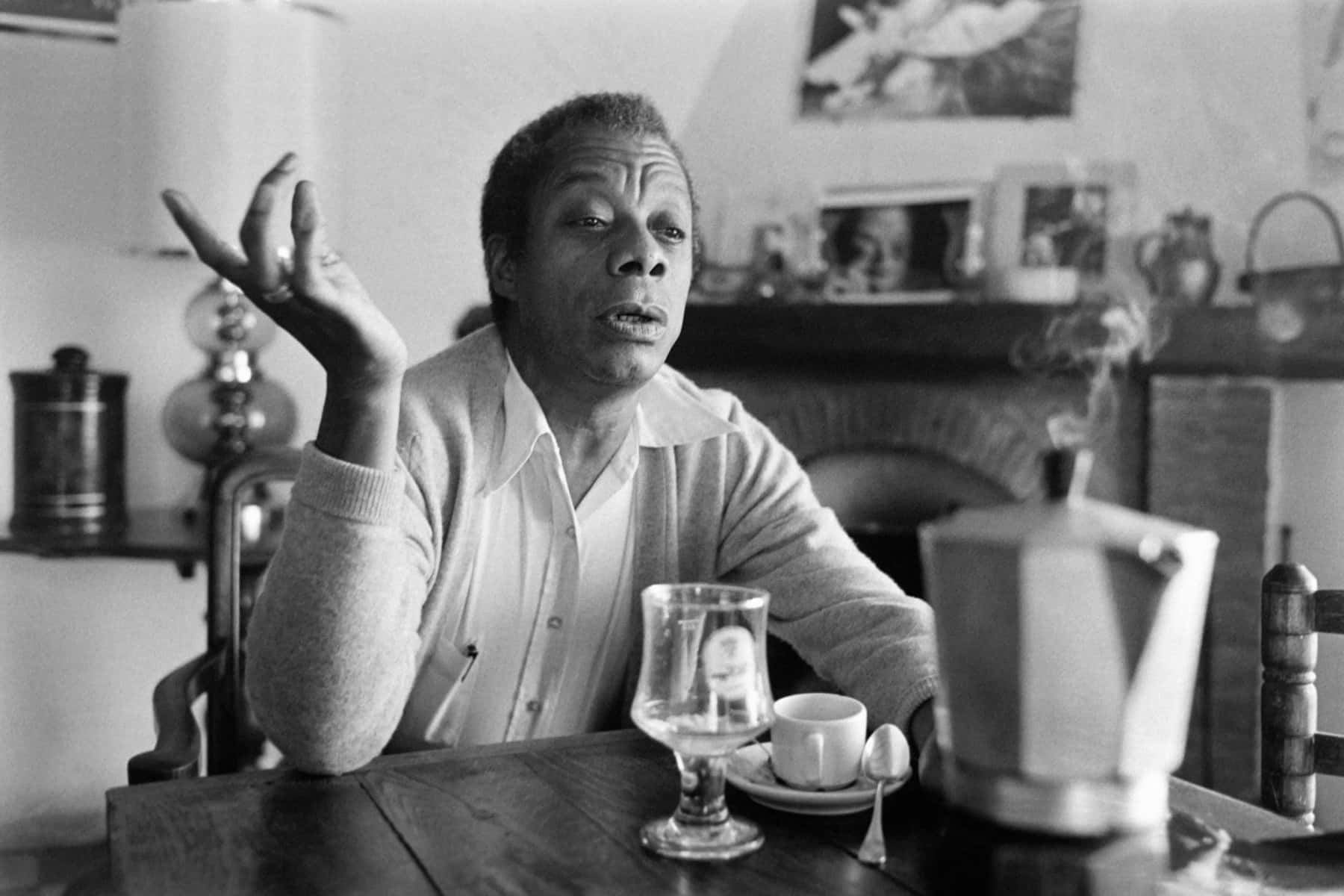

Honoring the loss and the inestimable gifts left behind, we mark what would have been the 97th birthday of James Baldwin.

An incandescent writer, masterful orator, out gay Black man, and fierce advocate for justice who long and incisively spoke “the naked truth” about the racist history of a country “caught in the lie of their pretended humanism… cruelly trapped between what we would like to be and what we actually are.”

For Baldwin, despite efforts in his lifetime to heal the divide, the fault lines of always-inextricable race and power remained brutally clear, often outlined in the righteous, lyrical cadences of the pulpit he grew up in but left behind, deeply disillusioned.

“What White people have to do is try and find out in their own hearts why it was necessary to have a nigger in the first place,” he wrote. “Because I’m not a nigger, I’m a man. But if you think I’m a nigger, it means you need it.”

On his side, for Black brothers and sisters “forced each day to snatch (our) identity out of the fire of human cruelty,” “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost all of the time.” Having long been deemed less than fully human by White people who “never had to look at me” while “I had to look at you,” he adds, “I know more about you than you know about me.”

Baldwin was born in Harlem on August 2, 1924 into “the raging inferno” of segregated America. His father, a preacher and powerful figure in his life, worked at a bottling plant; his mother was a domestic worker who raised nine children, with James the eldest. He found political and literary mentors in some progressive Jewish teachers, but there was no money for college, “on every street corner I was called a faggot.”

He wrote dazzlingly, “The wages of sin were visible everywhere, in every wine-stained and urine-splashed hallway, in every clanging ambulance bell, in every scar on the faces of the pimps and their whores, in every helpless newborn baby being brought into this danger, in every knife and pistol fight on the avenue and in every disastrous bulletin” – a cousin suddenly gone mad with her six kids parceled out, an aunt’s “slow agonizing death in a terrible small room, someone’s bright son blown into eternity by his own hand, another turned robber and carried off to jail.”

He got into “the church racket” but still recognized “the fear that I heard in my father’s voice when he realized I really believed I could do anything a White boy could do, and had every intention of proving it” because, “a child cannot, thank heaven, know how vast and how merciless is the nature of power.”

He did, of course, get out. From a child who believed “you belong where White people have put you” to one who realized, “Whatever they were looking at, it wasn’t me” to an ex-pat in Paris to an electrifying novelist, essayist, social critic, playwright, poet, public intellectual, FBI-hounded activist and revolutionary touchstone for the ongoing struggle for racial justice.

Baldwin is always the most potent narrator of his own “tale of how we suffer, and how we sometimes triumph.” His truth-telling was unsparing but elegant: “I imagine one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, they will be forced to deal with pain… Whatever White people do not know about Negroes reveals, precisely and inexorably, what they do not know about themselves… Love each other, unless your disagreement is rooted in my oppression and denial of my humanity… It is certain, in any case, that ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have… I can’t believe what you say because I see what you do.”

As an artist and activist among many “in our uneasy rage and splendor,” he said, “It was our privilege, to say nothing of our hope, to make the world a human dwelling place for us all.”

Baldwin’s eloquence and rage – “what is unspoken by the subjugated, what is never said to the master” – lived side by side, both keenly aware of history. In his epic 1965 debate with William Buckley at Cambridge, he decreed the American Dream is in fact at the expense of the American Negro: “I picked the cotton, and I carried it to the market, and I built the railroads under someone else’s whip,” he said, adding, his majestic voice rising, “For nothing.”

In the extraordinary 2016 film I Am Not Your Negro, director Raoul Peck used Baldwin’s own posthumous words to explore race in America through the lives and murders of his three friends Medgar Evers, Malcom X and MLK. “The story of the Negro in America is the story of America,” it declares, “and it is not a pretty story.” It is also, he noted, the story of any White-ruled, so-called democracy: “That great Western house I come from is one house… Simply, I am the most despised child of that house.”

“It comes as a great shock, around the age of five or six or seven, to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, when you were rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians were you,” he said. “It comes as a great shock to discover the country which is your birthplace and to which you owe your life and your identity has not in its whole system of reality evolved any place for you.”

For decades, Baldwin interrogated, excoriated and mourned that forced dispossession, recognizing that, “when you try to stand up and look the world in the face like you had a right to be here,” you enjoin White Americans to look at their life “and be responsible for it.” In 1962, Baldwin wrote what the New Yorker calls “the essay of his life,” a searing portrait of race, class, history and lack of accountability that became The Fire Next Time.

He described the Black child born into “a threatening world” where ” White people hold the power;” the Black World War II soldier “wearing the uniform of his country, a candidate for death in its defense, (who) is called a nigger by his comrades-in-arms” (and) comes home to “see the signs saying White and Colored” and is “told to ‘wait;'” the Blacks who don’t want to be “accepted” or “loved” by White people but “simply don’t wish to be beaten over the head by the Whites every instance of our brief passage on this planet.”

“The future of the Negro in this country (is) precisely as bright or dark as the future of the country,” he argued, dependent on the dubious ability of White Americans “to face the fact that I am flesh of their flesh, bone of their bone, created by them.” 60 years ago, he acknowledged, that acceptance “will not be tomorrow, and may very well be never.” We are still waiting.

Abby Zimet

Rаlph Gаttі