Take a mental trip back in time with me. A historical look back at some key dates in African American history.

1619: Africans were kidnapped and transported across the Atlantic Ocean and forced into slavery. The first known group brought to America were taken to Fort Comfort in Virginia this year. The forced enslavement of Africans in America continued for 244 years.

January 1, 1863: President Abraham Lincoln’s executive order on this date declared “that all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” This marked the official ending of the enslavement of Blacks in the United States. This was only done as a result of a long and brutal civil war between the North and South. At that time, there were approximately 3.5 million enslaved African Americans. To understand how many people that was, the estimated population of Chicago in 2020 was 2,677,643.

June 19, 1865: The last group of African Africans, in Galveston, Texas, were notified by Union soldiers about the ending of slavery. This was two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Juneteenth is celebrated annually as Freedom (Liberation) Day.

This historical timeline was necessary for me to set the context about the significance of my recent trip to Tulsa, Oklahoma. The Emancipation Proclamation changed the legal status of Blacks in America, but in many ways freedom, full citizenship continued to be denied. This included Jim Crow laws, lynchings, segregation, and systemic racism at every level. Despite the barriers, in approximately 1908, Blacks in Tulsa, Oklahoma formed a business community. The Tulsa community did so well that it garnered the attention and a visit from Booker T. Washington.

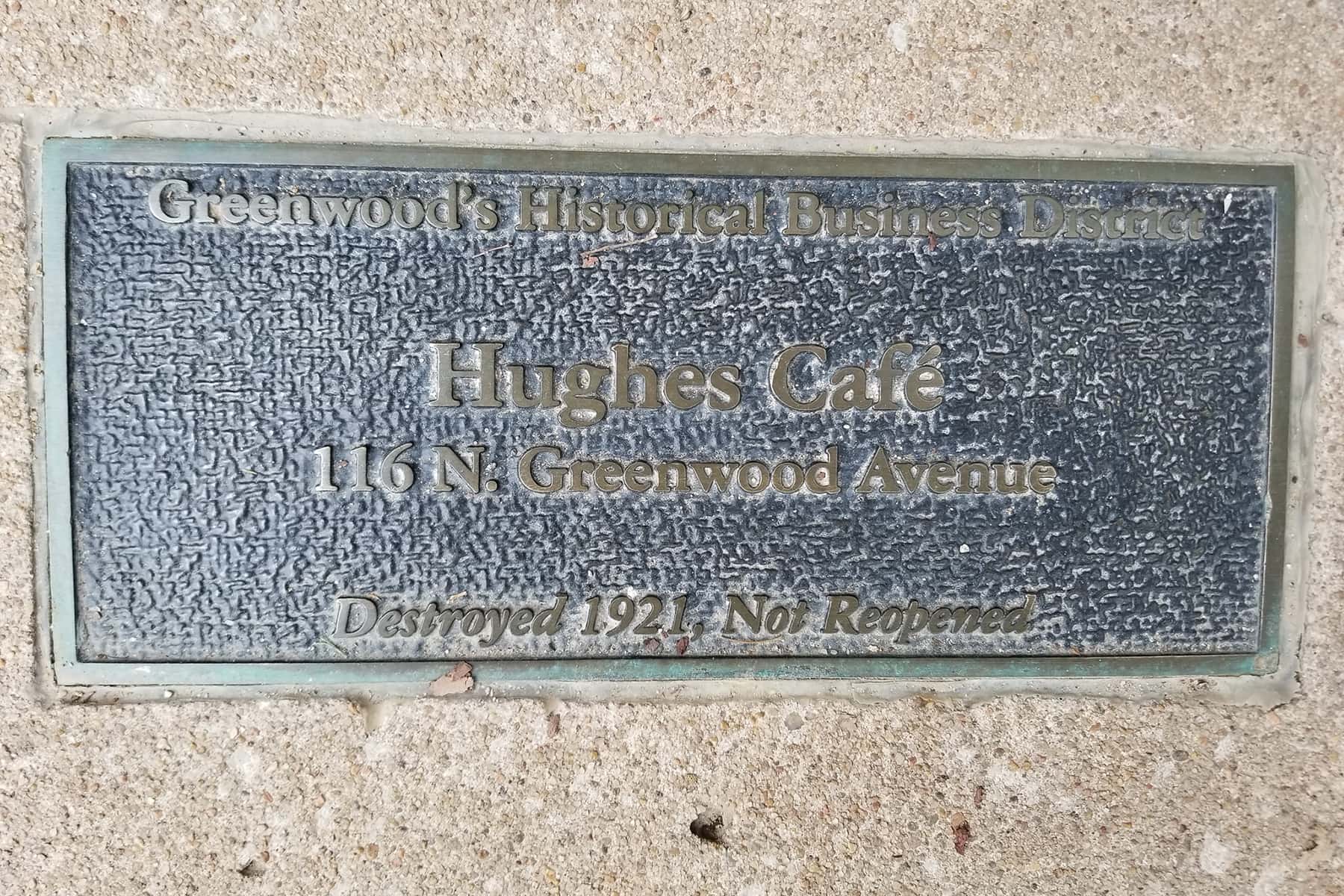

It was named the Greenwood District to model Washington’s vision for the self-sustaining Black community he formed at the edge of Tuskegee, Alabama. The District became known as Black Wall Street because of how successful the businesses were. By 1921, there were approximately 2000 businesses, homes, schools and churches within a nearly 40 blocks radius.

Imagine, in just a span of fifty-six years, from the time of the Emancipation Proclamation until 1921, Blacks built a thriving community filled with successful business, churches and homes. The money was circulating within Greenwood, and it continued to grow as a result. Keep in mind, although Blacks were “free” at the time, life was not easy.

The freedom did not come with any form of reparations. They endured daily hardships just to survive. The legal status of Blacks in the United States changed, yet the inhuman treatment didn’t. At this time, the Ku Klux Klan was formed, committing atrocities against Blacks on a daily basis, including lynchings.

In a short span of two days, the success of Greenwood was destroyed.

May 31 to June 1, 1921: The White community of Tulsa viewed the success of Greenwood as a threat. The success of the self-contained community meant that the White businesses were not getting money they felt they had rights to. Under the pretense (lie) of a Black teen boy being accused of assaulting a White teen girl. A White mob attacked and destroyed Greenwood. They looted the businesses and then set them on fire. The devastation was massive. Hundreds of Blacks were killed and buried in unmarked graves. To this date, the Tulsa Race Massacre is the most extreme incident of racial violence in United States history.

Fast-track to 2021: I traveled to Tennessee and then Texas at the end of May to visit family. My return route home had me driving through Oklahoma. With this year being the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre, I felt compelled to not just drive through Oklahoma, but to also visit Tulsa. I often seek out Black historical sites when I travel, but visiting Tulsa was much more than just a cultural sightseeing adventure for me.

As a Black entrepreneur, it was more like a pilgrimage for me. I had a lot of miles to travel from northern Texas back to Milwaukee, so my plan on the morning of June 3rd was to drive to Tulsa, spend a few hours there and then get back on the road. From the moment I drove into the area that once was a thriving Black community of entrepreneurs, I felt like my ancestors were welcoming me to sacred grounds. My supposed few hours of sightseeing turned into two days of walking the streets attempting to explore all that I could. I’m glad my visit was after the major centennial activity. The streets were not as crowded and I could freely walk and reflect on what once was.

“A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin, and culture is like a tree without roots.” – Marcus Garvey

As a Black entrepreneur, I was inspired by the success of the Black businesses during the pre-civil rights era. In 1921, Blacks were still being lynched and faced extreme disparities in economics, politics, education, housing, etc. The Ku Klux Klan wreaked havoc against Blacks with their campaigns of violence and terror. Yet, Blacks were able to have thriving businesses of all kinds in an approximately 40 square block neighborhood, with Greenwood and Archer Streets at its center. As a Black entrepreneur in 2021, their success had great significance to me.

The area I toured is very different from that of 1921. The only building that still contains some of its original structure is that of Vernon AME Church. Many Blacks hid in the basement of the church during the race massacre. The church was rebuilt and now stands as a testament to what once was. There have been repeated efforts to rebuild Black Wall Street, but the creation of a highway through the middle of the neighborhood and the Civil Rights Movement opening the way for integration, has prevented it from ever regaining its prominence.

When I think back to my visit to Greenwood, I can’t help but compare it to what was once a thriving Black community in Milwaukee. In the early 1900’s, Milwaukee’s Bronzeville was our version of Black Wall Street. Blacks were segregated into a small geographical area and made the best of it. The heart of the approximately 12-block community was Walnut Street. The main hub for businesses was on 3rd Street, what we now know to be Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive. I have a book by Paul H. Greenen on Milwaukee’s Bronzeville. As I flip through the pages and look at the many photos, there are striking similarities between photos I see from Black Wall Street. The community included beauty and barbershops, restaurants, hotels, social and recreational centers, banks, night clubs, offices for realtors, lawyers, accountants, and such.

We even had a newspaper, the Wisconsin Enterprise Blade. Anthony Josey started publishing it in 1925. He was a staunch advocate of shining a light on issues affecting the African American community. Bronzeville was where Duke Ellington and other major Black entertainers frequently performed and stayed in the hotels or with families because they couldn’t stay in the ‘Whites only’ hotels. Bronzeville wasn’t destroyed by a race riot, but by the development of public housing and the major blow was from the bulldozing of a significant part of the community to make way for Interstate 43 in 1948. Just as was the case with Greenwood, Milwaukee families displaced by the government for the public developments were not given any form of restitution.

Ironically, Milwaukee has had one of the longest running Juneteenth celebrations in the nation. This year marks the 50th anniversary. The parade and festival occur on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, along the same street that once was full of thriving Black businesses. I’m originally from Ohio and spent much of my childhood in Milwaukee. One of the fond childhood memories I have is of living on Lloyd Street just off of then 3rd Street. At that time, the Juneteenth festivities were pretty much at my doorstep. The only photo I have of me with my mother is from us taking a picture at the festival. Sadly, like Greenwood, Bronzeville is a fraction of what it was in its heyday. It is good to see the continual efforts to revive it.

The Tulsa Race Massacre was tragic. Survivors have spoken of how they saw nothing but black smoke from fires that continued throughout the night. Planes dropped bombs and Blacks were shot as they tried to flee. The National Guard wasn’t there to protect Blacks, but to treat them as if they were the perpetrators of the hideous crimes and put them in internment camps. Their businesses were looted and burned to the ground. More than 10,000 were left homeless and forced to live in tents throughout the winter as they tried to rebuild their lives. The process of rebuilding was filled with barriers. They were blocked from getting lumber, permits, financing, etc. All this occurred without anyone being held responsible or the victims receiving restitution. The unpaid financial claims were at least $2,719,745.61.

As I toured the former Black Wall Street area, it was great to see Black businesses continuing the great legacy of what was once a bustling business district. I talked with one business owner whose hair salon is now on the grounds where the last business was burned in 1921. Her last name is the name that was on the building, a sign that confirmed she was opening her salon at the right location. I purchased an item from a store owner who beamed with pride as we talked about her new convenience store in the historic district. She shared with me how her 80+ year old mother tells her stories of what it was like growing up in the area. Now she is a part of a new resurgence with her business in the Greenwood District.

Although what happened in 1921 weighs heavy on my heart, I am still inspired by the entrepreneurial spirit of the original Black Wall Street business owners and those who rebuilt businesses immediately after the destruction. At times, the process of maintaining a successful business seems overwhelming to me. But I have examples of those who faced far greater challenges and still achieved success.

Here are some key lessons that I will lean on as necessary: continue to tap into my expertise; prove others wrong when they say I can’t do something; when resources are limited, do a lot with a little; join forces with like-minded entrepreneurs for inspiration and support; learn lessons from setbacks and keep pushing forward; and when things seem like they are at their worst, out of ashes greatness can rise.

Relatively speaking, 100 years ago was not that long ago. There are many things that are different now, but there are many things that continue to persist. Blacks and Black entrepreneurs in 2021 face inequities. As I continue to focus on growing my business as a Black entrepreneur, I will forever remember and be inspired by the historic Black Wall Street.

As I sit at my desk working my business, all I have to do is glance up to be reminded of the entrepreneurial spirit of the Black business trailblazers. A top priority of mine when I returned home was to purchase a frame for my Black Wall Street poster. It now hangs on my wall in a gold double matted frame.

© Photo

Clarene Mitchell and Lee Matz