Members of C.K. Pier Badger Camp #1 and descendants of John Afton gathered on May 22 to honor him on the 150th anniversary of his death. Pvt. Afton was the first veteran buried at Wood National Cemetery.

Penny Afton-Sage drove from Grand Rapids, Michigan to Milwaukee last fall to try to find the grave of her great-great-great-grandfather, Pvt. John Afton. She arrived at Wood’s administrative address of 5000 W. National Avenue, but saw no cemetery nearby. When Afton-Sage did find a cemetery in the area, she walked around for two hours looking for her ancestor’s headstone. However, she was actually in Calvary Cemetery, with Wood being located on the other side of the power transmission lines.

She eventually left empty-handed and exasperated.

Unknown to her at the time was that the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War – C.K. Pier Badger Camp #1 had plans to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Pvt. Afton’s burial. Organized in 1881 and chartered by Congress in 1954, the organization is the legal heir and successor to the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR).

Tom Mueller, a past commander of the Camp who had a great-great uncle in a Wisconsin cavalry regiment during the Civil War, e-Mailed Afton-Sage in the spring, because she had put a brief biography of Pvt. Afton on the “Find a Grave” website a year ago. Pvt. Afton’s status as the first veteran buried at Wood was well-known in the local history and patriotic communities, and the Camp wanted to hold a Sesquicentennial event to honor him.

“You have ‘no idea’ how excited I am to hear from you. We spent a night in Milwaukee and, of course, my main interest in the beautiful city was to check out John’s grave. I was so disappointed!” responded Afton-Sage to Mueller’s e-Mail. She went on to characterize her visit, unaware that she had been at the wrong cemetery. “We were very impressed with the old building at the old entrance of the cemetery. There was no one in the building nor was there anyone else wandering around the cemetery. We were alone to find and visit John’s grave. We attempted to use the map at the gate kiosk to find our way around but were unsuccessful. The cemetery has very few section markers and it is not easy for newbies to navigate.”

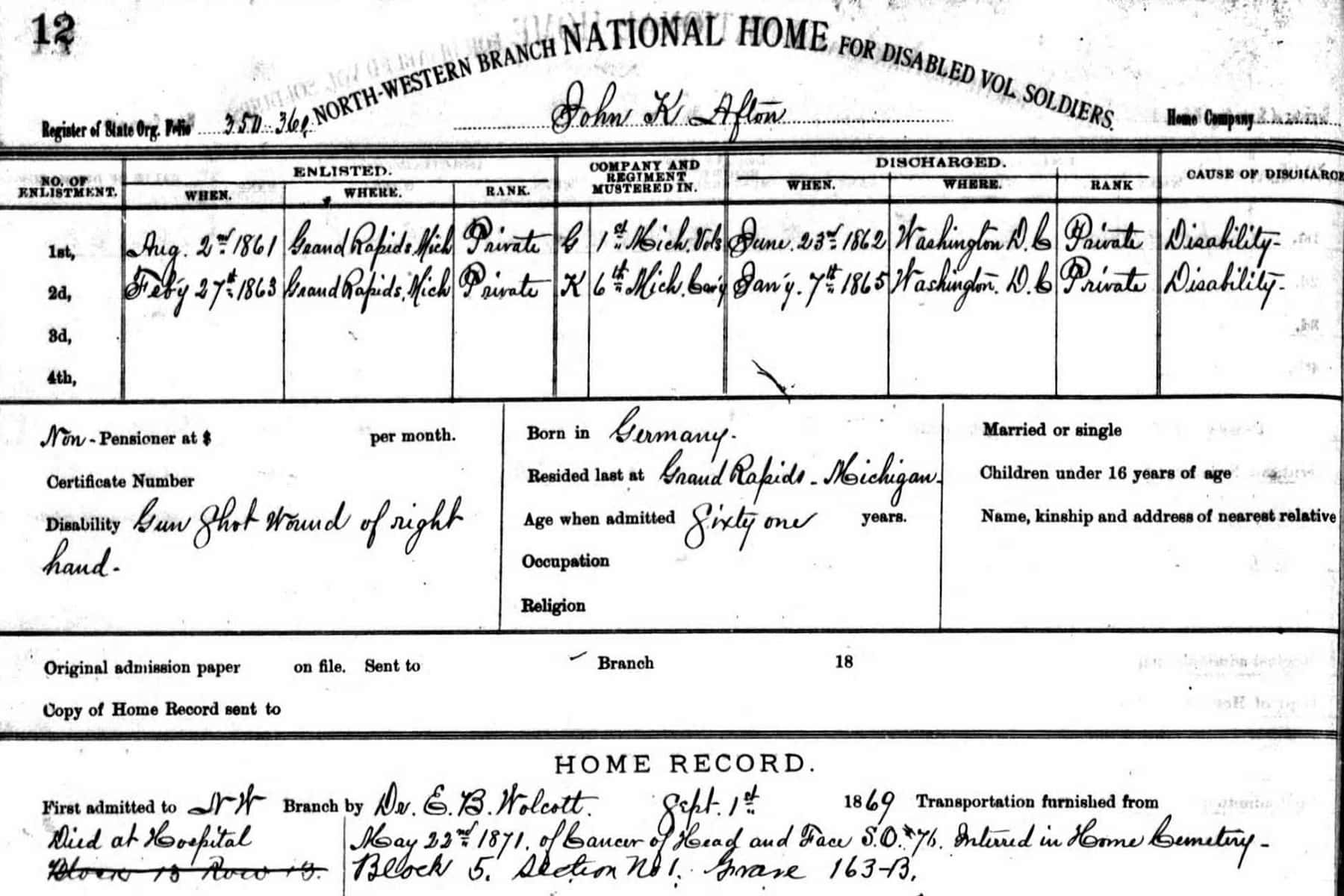

A native of Grand Rapids, Pvt. Afton came to Milwaukee on September 1, 1869, to stay at what was then the Northwestern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers – which had just opened in 1867.

He died of cancer less than two years later on May 22, 1871, and was buried the same day at what is now Wood National Cemetery. Pvt. Afton was the first person to be interred at the site that would become Wisconsin’s only national military cemetery.

For the May 22 COVID-safe commemoration, members of the Camp guided Afton-Sage to her ancestor’s grave. She was joined by a handful of Michigan relatives, with the youngest being a fifth-generation descendant of Pvt. Afton.

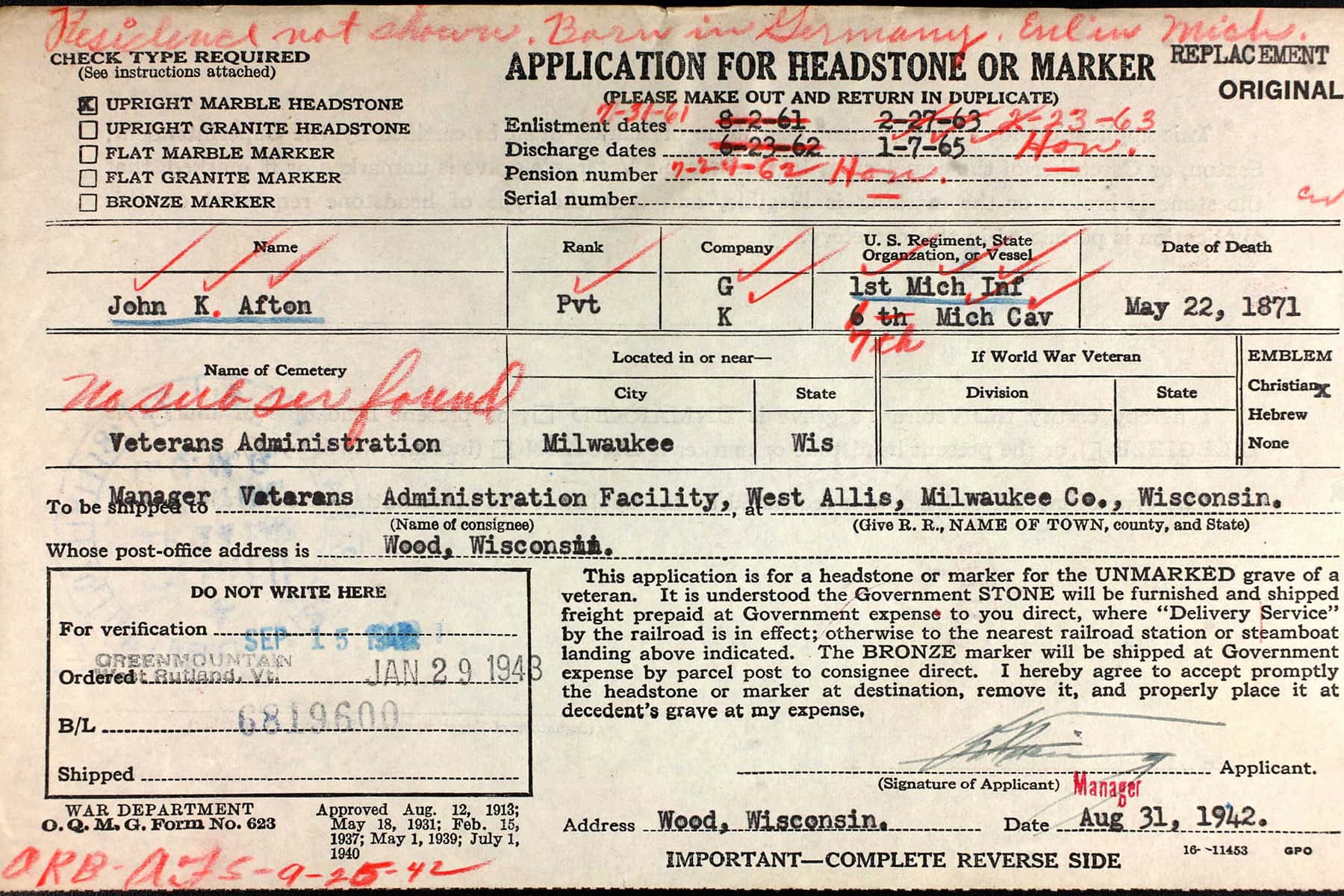

Afton-Sage has worked on her family’s genealogy for more than three decades. She researched Pvt. Afton’s life and journey, from his birth in Germany in 1808, to his immigration to America in 1836, and his two enlistments during the Civil War – including being wounded and taken prisoner at Gettysburg. He went on to become a farmer in an area near Ann Arbor, Michigan, after the war and had eight children with is wife.

His headstone is located in the isolated area on the north side of I-94, just south of the power lines and west of the overpass bridge, in Section 5- II, Grave 163B. Calvary Cemetery is on the other side of the power lines, as is Section 1 of Wood National Cemetery.

While his headstone says 1st Michigan Infantry, Pvt. Afton’s record at the Soldiers Home revealed a fascinating twist of his story: He also served in the 7th Michigan Cavalry and was captured at Gettysburg. He was around age 53 at the time. The 7th Cavalry made a dramatic saber charge four miles east of Gettysburg, at the farm of John and Sarah Rummel on July 3, led by 23-year-old Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer.

“The 7th Cavalry leader, Colonel William D. Mann, waved them forward. Suddenly, George Custer appeared at the head of the regiment. He was a warrior with a cause, following a road to glory. … Fearless, he would not ask men to go where he would not lead them. Turning in his saddle, he shouted, ‘Come on, you Wolverines.’ Custer had removed his hat, and his long blond hair was flying above his shoulders. The 7th raised a cheer and kept shouting as it broke into an open field and barreled down like a locomotive, full steam, on the Rebel line. Although they held the edge in numbers, the Johnnies were all on foot, and the sight of those tearing hooves, rushing horses, and wicked, waving sabers sent them running for their reserves. Custer and his Wolverines kept after them, riding down many and taking them prisoner. The charge seemed irresistible, but then the 7th Michigan topped a small rise – and ran smack into a low, stone wall with a high post-and-rail fence fixed on top of it. The lead squadrons were going too fast to stop, and those behind could not see the barrier ahead. ‘We crashed against the stone wall, which withstood us,’ remembered one of the 7th’s captains. ‘It broke our columns into jelly and mixing us up like a mass of pulp.’ Virginians and Michiganders were face-to-face at point-blank range. … The fury swirled along the fence as nearly 700 men used sabers, revolvers and carbines. Custer’s horse was struck, and he borrowed a bugler’s mount. Numbers of Michiganders dismounted and knocked down sections of the fence. Through the gaps the Yankees went, pell-mell. The breakthrough scattered the Virginians, who bolted up the hillside. The Michiganders pursued. Coming toward them, however, were more mounted rebels from multiple regiments. The 7th stuck manfully to its ground, fighting back with carbines and revolvers. Col. Mann called it a ‘desperate, but unequal, hand-to-hand conflict.’ It grew uglier by the minute. The assailants were so close that they burned each other when they fired their weapons. All the while, the Wolverines were helplessly trapped in a galling stream of musketry from a Confederate line being continuously reinforced. The 7th Michigan had shattered an enemy attack only to be repulsed by an overwhelming counter-thrust. Now it fell back, and soon two more Michigan cavalry regiments galloped into the fray.” – “Gettysburg: Day Three,” by Jeffry D. Wert and “Custer victorious” by Gregory J.W. Urwin

Somewhere during the battle, Pvt. Afton was wounded in the right hand and later taken prisoner by Confederate troops. Thirteen men in the 7th Cavalry were killed on July 3, and 52 wounded. Pvt. Afton and 38 others were captured or missing. He did not return to his unit until October 1. It is not known whether he was a horseman or support staff.

From his pension application filed April 28, 1865, Pvt. Afton “was wounded in his right hand on the third day of July 1863 either by a piece of shell or by buckshot at the Battle of Gettysburg.”

“In May 1864, whilst in camp with his regiment in Virginia, near City Point, about the last of May or first of June he was attacked with chronic diarrhea with which he has suffered ever since. At the same time he was also attacked with bronchitis from which he still suffers.”

Pvt. Afton received a disability discharge from the 7th Cavalry on December 1, 1864, and from the 1st Infantry on June 24, 1862, where he served in Company G for 11 months. When Pvt. Afton died in 1871, the Grand Army of the Republic was only 5 years old. A few years ago, the Camp did a comprehensive census of the Civil War vets at Wood Cemetery.

“The cemetery had never done a count of the Civil War vets. The project took nearly a year and a half and our total is 5,980. The VA had said John Afton was No. 1, and our project drew the same conclusion,” said Steve Michaels, past national Commander-in-Chief at C.K. Pier Badger Camp #1, SUVCW.

Tom Mueller

Lee Matz