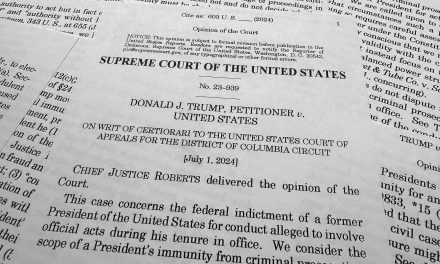

The Senate acquitted former president Donald Trump on February 13 of the charge of inciting an insurrection. Fifty-seven senators said he was guilty; 43 said he was not guilty. An impeachment conviction requires a two-thirds majority of the Senate, so he was acquitted, but not before seven members of his own party voted to convict him.

The only real surprise was when five Republicans joined 50 Democrats to vote in favor of calling witnesses. That vote came after Representative Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-WA) last night released a statement recounting an angry conversation between House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) and Trump during the violence, in which Trump refused to call off the rioters and appeared to taunt McCarthy by telling him that the rioters were “more upset about the election than you are.”

Herrera Beutler’s statement suggested that Trump had deliberately abandoned Vice President Mike Pence and the lawmakers to the insurrectionists, although Trump’s lawyer had definitively declared during the trial that Trump had not been told that Vice President Mike Pence was in danger.

The vote to hear witnesses threw the Senate into confusion as senators were so convinced the trial would end that many had already booked flights home. The House impeachment managers said they wanted to call Herrera Beutler to testify; Republican supporters of Trump warned they would call more than 300 witnesses, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Vice President Kamala Harris.

After the two sides conferred, the House managers gave up demands for witnesses in exchange for reading Herrera Beutler’s statement into the record as evidence. While there was a widespread outcry at what seemed to be a Democratic capitulation, there were reasons the Democrats cut this deal. Witnesses to Trump’s behavior, like McCarthy, did not want to testify and would have been difficult. The Republicans as a group would have dragged the process on well into the spring, muddying the very clear story the impeachment managers told. They allegedly said that if the Democrats called witnesses, they would use the filibuster to block all Democratic nominees and legislation.

So much pundits have noted. But the day was not just about Trump; it was part of a longer struggle for the future of the country.

Trump’s lawyers proceeded in the impeachment trial with the same rhetorical technique Trump and his supporters use: they flat-out lied. Clearly, they were not trying to get at the truth but were instead trying to create sound bites for right-wing media, the same way Trump and the rest of his cabal convinced supporters of the big lie that he had won, rather than lost, the 2020 election. In that case, they lied consistently in front of the media, but could not make anything stick in a courtroom, where there are penalties for not telling the truth.

In the first impeachment hearings, Trump supporters did the same thing, shouting and lying to create sound bites, and while the sworn testimony was crystal clear, their antics left many Americans convinced not of the facts but that then-President Trump was being persecuted by Democrats who were trying to protect Hunter Biden.

So, while it is reasonable to imagine that witnesses would illustrate Trump’s depravity, it seems entirely likely that, as Trump’s lawyers continued simply to lie and their lies got spread through right-wing media as truth, Americans would have learned the opposite of what they should have.

Instead, the issue of Trump’s guilt on January 6 will play out in a courtroom, where there are actual rules about telling the truth. Trump’s own lawyers suggested he should answer for his actions in a court of law, and in a fiery speech after the vote, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell set up the same idea. But even if that does not happen, the Capitol rioters will be in court, keeping in front of Americans both the horrific events of January 6 and their contention that they showed up to fight because their president asked them to.

The constant refrain of the January 6 insurrection mirrors the Republicans’ use of sham investigations to convince people that Democrats are criminals—think, for example, of former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s emails—except, this time, the cases are real. This should address the problem of manufactured sound bites, and should benefit the Democrats with voters, especially as Republicans are now openly the Party of Trump.

McConnell tried to address the party’s capitulation immediately after the vote with a speech blaming Trump for the insurrection and saying that his own vote to acquit was because he does not think the Senate can try a former president. This is posturing, of course; McConnell made sure the Senate did not take up the House’s article of impeachment while Trump was still in office, and now says that, because it did not do so, it does not have jurisdiction.

McConnell is trying to have it both ways. He has made it clear he wants to free the Republican Party from its thralldom to Trump, and he needs to do so in order to regain both voters and the major donors who have distanced themselves from party members who support the big lie. But he needs to keep Trump voters in the party.

He has bowed to the Trump wing in the short term, apparently hoping to retain its goodwill, and then, immediately after the vote, gave a speech condemning Trump to reassure donors that he and the party are still sane. He likely hopes that, as the months go by and the Republicans block President Biden’s plans, alienated voters and donors will come back around to the party. From this perspective, the seven Republican votes to convict Trump provide excellent cover.

It is a cynical strategy and probably the best he can do, but it is a long shot that it alone will enable the Republicans to regain control of the House and the Senate in 2022. For that, the Republicans need to get rid of Democratic votes.

That need was part of what was behind the party’s support for Trump’s big lie. The essence of that lie was that Trump won the 2020 election because the votes of Democrats, especially people of color, were illegitimate. Republican lawmakers were happy to sign on to that big lie: it is a grander version of their position since 1986. Even now, those Republicans who backed the big lie have not admitted it was false. Instead, they are using the myth of fraudulent Democratic votes to push a massive attack on voting rights before the 2022 election.

But they are no longer setting the terms of the country’s politics. By refusing to engage with the impeachment trial, President Biden and his team escaped the trap of letting Trump continue to drive the national narrative. Instead, they are making it a priority to protect voting rights. At the same time, they are pushing back against the Republican justification for voter suppression: that widespread voting leads to Black and Brown voter fraud that elects “socialists” who redistribute money from “makers” to “takers.”

President Biden’s team is using the government in ways that are popular with voters across the board: right now, for example, 79% of Americans either like President Biden’s coronavirus relief package or think it is too small.

It was disheartening to see that even trying to destroy the American government was not enough to get more than seven Republican senators to convict the former president. But it is not at all clear that tying their party to Trump is a winning strategy.

Wіn McNаmее

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics