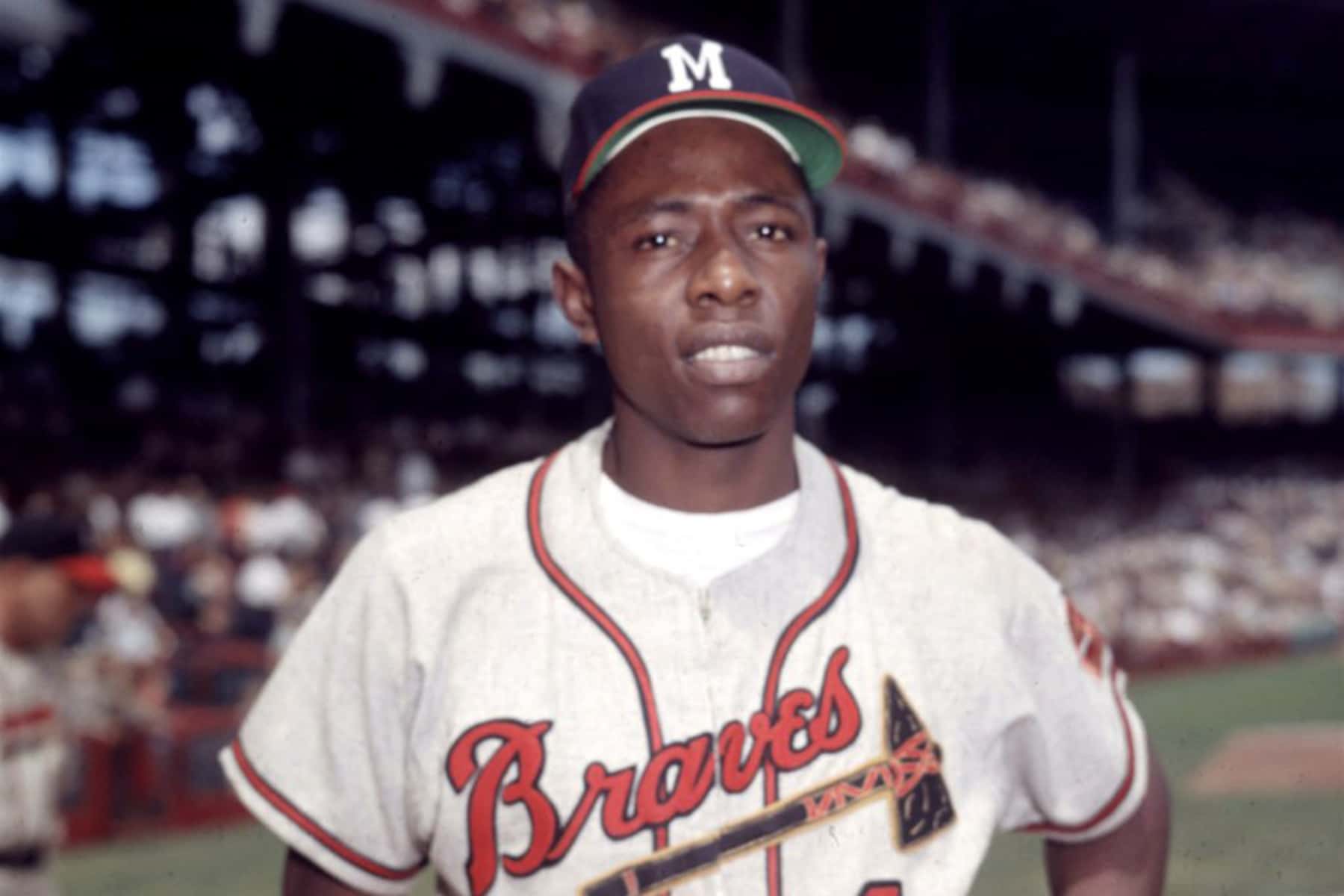

Hank Aaron, who endured racist threats with stoic dignity during his pursuit of Babe Ruth’s home run record and gracefully left his mark as one of baseball’s greatest all-around players, died on January 22. He was 86.

The Atlanta Braves, Aaron’s longtime team, said that he died peacefully in his sleep. No cause was given. Aaron made his last public appearance just in early January, when he received the COVID-19 vaccine. He said he wanted to help spread the to Black Americans that the vaccine was safe.

“Aaron was beloved by his teammates and by his fans,” said former baseball Commissioner Bud Selig, a longtime friend. “He was a true Hall of Famer in every way. He will be missed throughout the game, and his contributions to the game and his standing in the game will never be forgotten.”

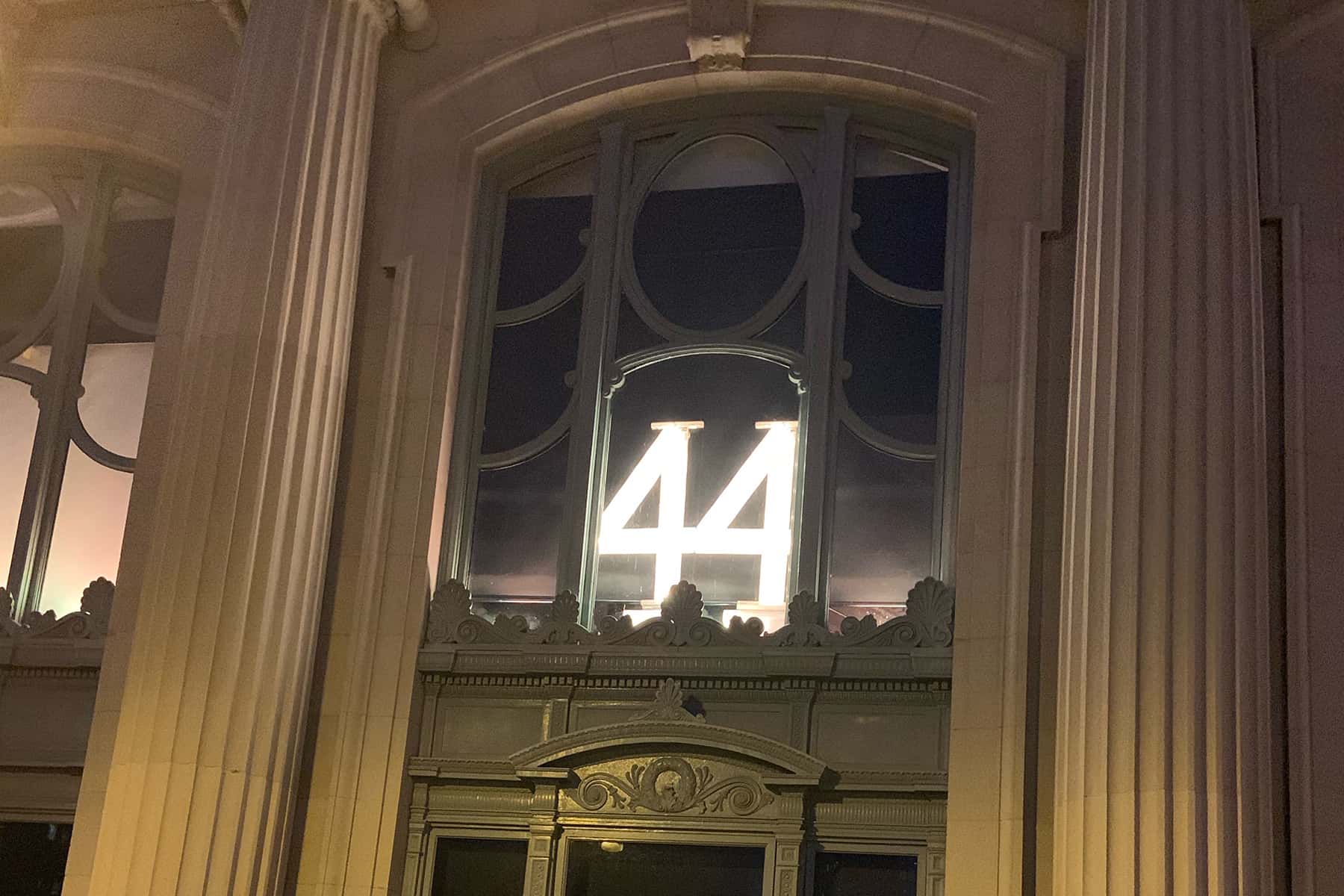

Nicknamed “Hammerin’ Hank,” the Hall-of-Famer broke Babe Ruth’s career home run record in 1974. Before a sellout crowd at Atlanta Stadium and a national television audience, Aaron hit No. 715 off Al Downing of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Aaron finished his career with 755 home runs, a record that would hold for more than 33 years, a period in which the Hammer slowly but surely claimed his rightful place as one of America’s most iconic sporting figures, a true national treasure.

Aaron’s journey to that memorable homer was hardly pleasant. He was the target of extensive hate mail as he closed in on Ruth’s cherished record of 714, much of it sparked by the fact Ruth was white and Aaron was Black.

“If I was white, all America would be proud of me,” Aaron said almost a year before he passed Ruth. “But I am Black.”

Aaron was shadowed constantly by bodyguards and forced to distance himself from teammates. He kept all those hateful letters, a bitter reminder of the abuse he endured and never forgot.

“It’s very offensive,” he once said. “They call me ‘nigger’ and every other bad word you can come up with. You can’t ignore them. They are here. But this is just the way things are for black people in America. It’s something you battle all of your life.”

After retiring in 1976, Aaron became a revered, almost mythical figure, even though he never pursued the spotlight. He was thrilled when the U.S. elected its first African-American president, Barack Obama, in 2008.

“Hank Aaron was one of the best baseball players we’ve ever seen and one of the strongest people I’ve ever met,” Obama said. “A child of the Jim Crow South, Hank quit high school to join the Negro League, playing shortstop for $200 a month before earning a spot in Major League Baseball. Humble and hardworking, Hank was often overlooked until he started chasing Babe Ruth’s home run record, at which point he began receiving death threats and racists letters-letters he would reread decades later to remind himself ‘not to be surprised or hurt.'”

Aaron spent 21 of his 23 seasons with the Braves, first in Milwaukee, then in Atlanta after the franchise moved to the Deep South in 1966. He finished his career back in Milwaukee, traded to the Brewers after the 1974 season when he refused to take a front-office job that would have required a big pay cut.

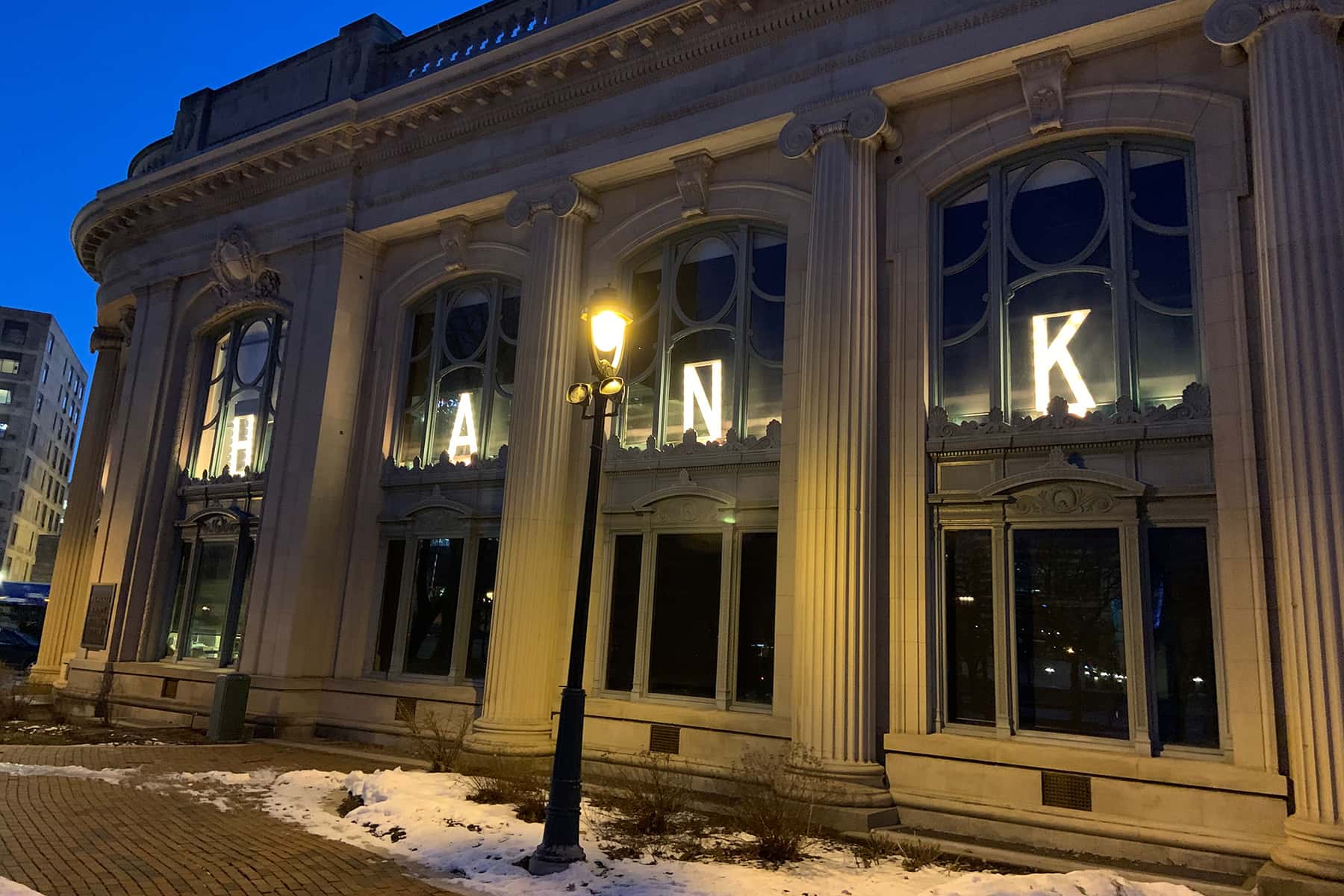

“We lost a legend. Hank Aaron was my childhood hero of heroes. He was an amazing person and a fantastic baseball player. He was such a big part of Milwaukee,” said Mayor Tom Barrett.

Aaron grew up in Mobile, Alabama. As a child, he dreamed of joining the Major Leagues, which then were segregated to exclude Black players. He started his professional baseball career in the Negro Leagues. Within two years, he joined MLB’s Milwaukee Braves.

Aaron continued to make appearances in Milwaukee. In 2012, he visited the Brew City to help publicize the expansion of the Hank Aaron State Trail, which stretches from downtown Milwaukee to Waukesha.

“I’m saddened to hear about the passing of a great athlete, a great man, and one of my own personal heroes,” said Governor Tony Evers. “When I was a kid, Hank Aaron actually came to Plymouth to meet and visit with my Cub Scouts group—something I cherished then and even still today. Hammerin’ Hank was a role model to so many both on and off the field, and he’ll be remembered as a legend to the sport and to our state. What a loss.”

Aaron never received the attention he deserved until late in his career. He played in only two World Series. He was stuck far from the media spotlight in Milwaukee and Atlanta.

“In my day, sportswriters didn’t respect a baseball player unless you played in New York or Chicago,” Aaron said during a 1999 interview. “If you didn’t come from a big city, it was hard to get noticed.”

Pаul Nеwbеrry

Major League Baseball and Steve Schaffer