By Sierra Carter, Assistant Professor of Psychology, Georgia State University

I am part of a research team that has been following more than 800 Black American families for almost 25 years. We found that people who had reported experiencing high levels of racial discrimination when they were young teenagers had significantly higher levels of depression in their 20s than those who hadn’t. This elevated depression, in turn, showed up in their blood samples, which revealed accelerated aging on a cellular level.

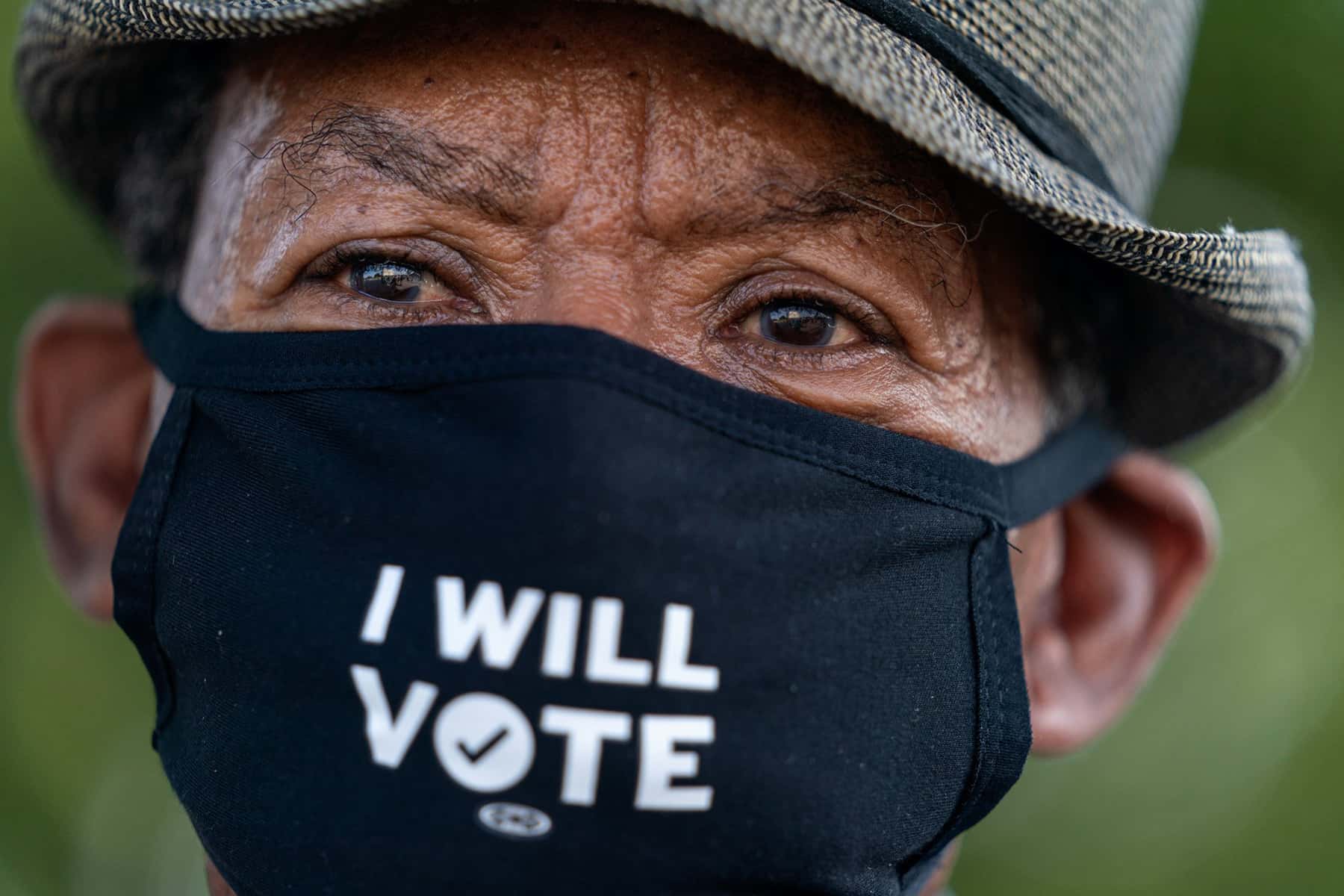

Our research is not the first to show Black Americans live sicker lives and die younger than other racial or ethnic groups. The experience of constant and accumulating stress due to racism throughout an individual’s lifetime can wear and tear down the body – literally “getting under the skin” to affect health. These findings highlight how stress from racism, particularly experienced early in life, can affect the mental and physical health disparities seen among Black Americans.

Why it matters

As news stories of Black American women, men and children being killed due to racial injustice persist, our research on the effects of racism continue to have significant implications. COVID-19 has been labeled a “stress pandemic” for Black populations that are disproportionately affected due to factors like poverty, unemployment and lack of access to health care.

In 2019, the American Academy of Pediatrics identified racism as having a profound impact on the health of children, adolescents, emerging adults and their families. Our findings support this conclusion – and show the need for society to truly reflect on the lifelong impact racism can have on a Black child’s ability to prosper in the U.S.

How we do the work

The Family and Community Health Study, established in 1996 at Iowa State University and the University of Georgia, is looking at how stress, neighborhood characteristics and other factors affect Black American parents and their children over a lifetime. Participants were recruited from rural, suburban and metropolitan communities. Funded by the National Institutes of Health, this research is the largest study of African American families in the U.S., with 800 families participating.

Researchers collected data – including self-reported questionnaires on experiences of racial discrimination and depressive symptoms – every two to three years. In 2015, the team started taking blood samples, too, to assess participants’ risks for heart disease and diabetes, as well as test for biomarkers that predict the early onset of these diseases.

We utilized a technique that examines how old a person is at a cellular level compared with their chronological age. We found that some young people were older at a cellular level than would have been expected based on their chronological age. Racial discrimination accounted for much of this variation, suggesting that such experiences were accelerating aging. Our study shows how vital it is to think about how mental and physical health difficulties are interconnected.

What’s next

Some of the next steps for our work include focusing more closely on the accelerated aging process. We also will look at resiliency and early life interventions that could possibly offset and prevent health decline among Black Americans. Due to COVID-19, the next scheduled blood sample collection has been delayed until at least spring 2021. The original children from this study will be in their mid- to late 30s and might possibly be experiencing chronic illnesses at this age due, in part, to accelerated aging.

With continued research, my colleagues and I hope to identify ways to interrupt the harmful effects of racism so that Black lives matter and are able to thrive.

Fаbrіcе Cоffrіnі and Jаcquеlyn Mаrtіn

Originally published on The Conversation as Racial discrimination ages Black Americans faster, according to a 25-year-long study of families

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.