In 1860, on the brink of civil war, caped young men with lanterns sought to safeguard democracy. Now, in a nation divided once more, the group has returned to the light.

On 21 September, a tweeted image of an eyeball, with the words “WIDE AWAKE,” accompanied an urgent appeal to demonstrators in Washington, eager to protest against Republican plans to nominate a supreme court replacement for Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

The tweet was part of a rapidly growing interest in the Wide Awakes, a shadowy youth movement that rose up in 1860, as the nation teetered toward civil war, then vanished. Now, in another bitterly divided moment, historians, journalists and even fashionistas are converging on the movement, which helped elect Abraham Lincoln.

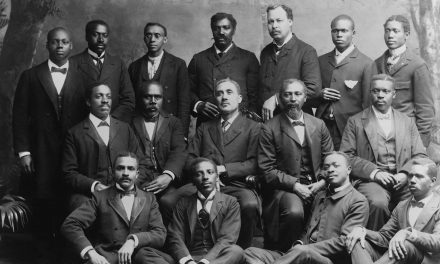

Who were the Wide Awakes? At any point in history, it can be hard to pinpoint a sprawling youth movement with no central organization. But thanks to surviving photographs, we have a strong sense of what the Wide Awakes looked like. They live on in old ambrotypes and daguerrotypes, staring out resolutely from the faded chemicals, serious young men returning the gaze of the camera.

There is no single collection – like the original movement, the surviving Wide Awakes are spread out, in libraries and old auction catalogues, on eBay and through the half-life of Pinterest, where so many images refuse to die.

We know, from the historical record, that the Wide Awakes began to assemble in Hartford, Connecticut, on the night of 25 February 1860. An anti-slavery politician from Kentucky, Cassius Clay, came to speak. Escorting him, a group of young men formed a parade by torchlight. Someone improvised a cape, made out of oilcloth, to protect his clothes from the dripping oil of the torches. He was quickly imitated – a dashing new look was born.

A week later, the first Wide Awake Club was formed in Hartford. Thirty-six young men agreed to buy their own capes, just in time for the next political visitor. On 5 March, he arrived, an unusual speaker from Illinois, gaunt and angular. Lincoln had just given his great speech at the Cooper Union in New York, and as one observer put it, the “presidential bee” had begun to buzz around him. That night in Hartford, the Wide Awakes lit their torches, donned their capes and escorted Lincoln to his hotel.

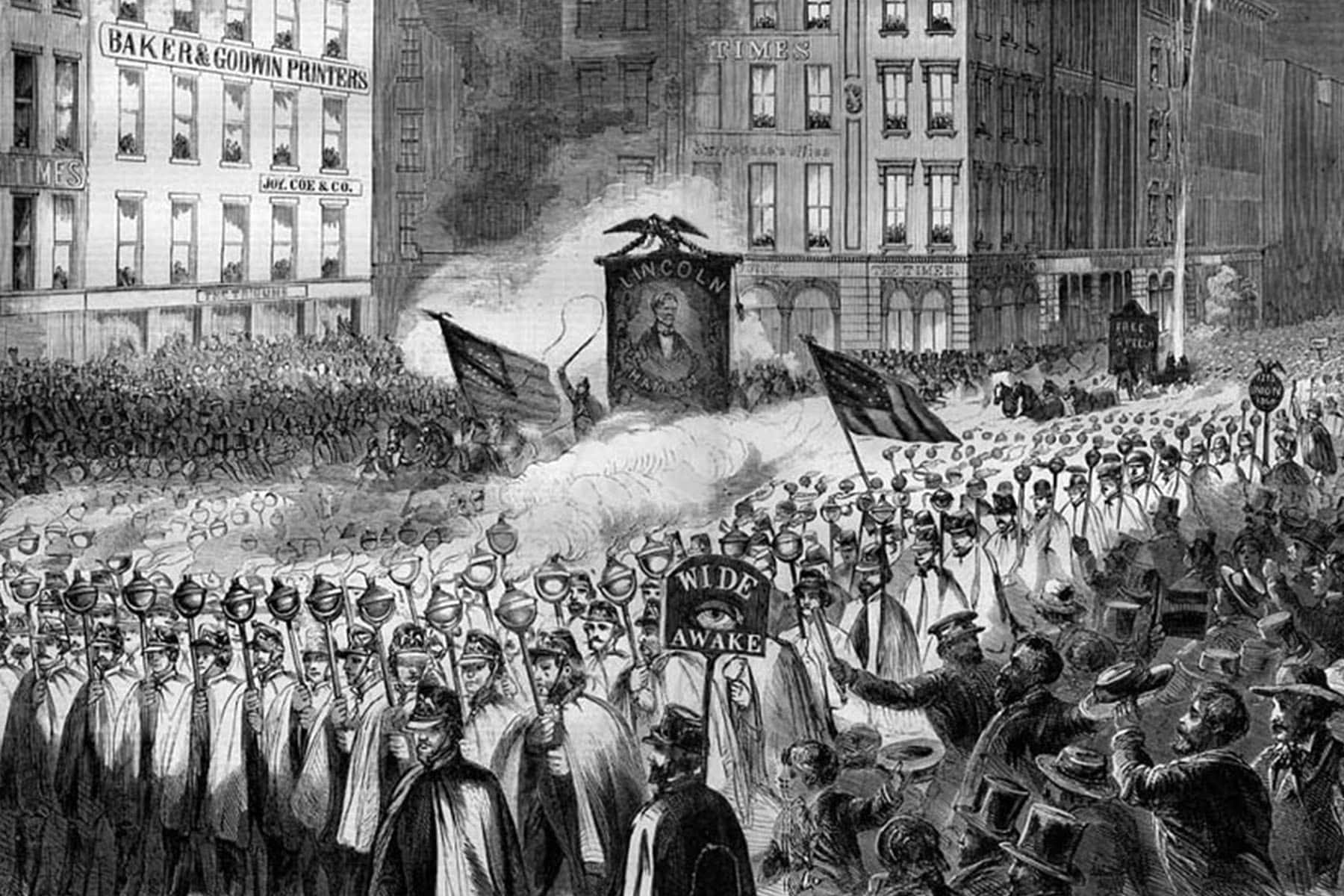

The new look spread like … wildfire. The capes were splendid, especially when augmented by military caps, the flickering light of the torches and all those painted eyeballs, staring out from large banners.

But it was not just a look. It was a genuine feeling, as if young people were waking from a long slumber, and seeing for the first time how much corruption and rot had set in. The country was very young: 51% were 19 or younger. But for as long as anyone could remember, the government had been controlled by Washington’s largest lobby, the Slave Power, which selected mediocre presidents, eager to do its bidding, and placed compliant lackeys on the supreme court.

Three years earlier, in the Dred Scott decision, the court had ruled that black lives emphatically did not matter – that African Americans could never become citizens or hold any rights at all. The day before Lincoln came to Hartford, a large slave ship, the Clotilda, left Alabama for Africa, flouting all laws against the slave trade. Under President James Buchanan, slaveholders were free to do as they liked; as Frederick Douglass complained, slave traders actually flew the Stars and Stripes as they carried their human cargoes back from Africa.

But Lincoln and others had risen in protest against these injustices, which so clearly violated America’s founding ideals. Now the young were joining them, in huge numbers. They wanted their country back. An editor at the Atlantic Monthly wrote that the time had come to decide, once and for all, “whether the American idea is to govern this continent”. In defense of that idea, first hundreds, then thousands of Wide Awakes would pour into the streets in 1860.

The movement grew quickly in the spring and summer, with clubs forming across the north and midwest. Chicago had 48 clubs alone. Shrewdly, they used new networks of communication: one young writer improvised a kind of early comic book, Pipps Among the Wide Awakes, to celebrate the dashing caped crusaders.

It was a badge of honor to wear “the Cape of Good Hope,” as one called it, and they thrilled onlookers with huge nighttime parades, fireworks added to the torchlight, and “moving transparencies,” like slide shows, a distant ancestor of what would become cinema. Wide Awake sheet music was printed and quickly sent around the country, thrilling a nation of young people, waking up. Even the dour abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison wrote: “It was hard not to tap one’s feet to the jaunty rhythms.”

The clubs visited each other, and thousands watched the rallies, including large numbers of women, who formed groups of “Lady Wide Awakes”, sewed uniforms and linked the cause to their own fight for empowerment. A Wide Awake rally in Seneca Falls, New York, was addressed by Susan B Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, campaigners for women’s suffrage.

African Americans were occasionally invited to join the clubs, especially in Boston – deepening the south’s horror. Southern politicians ridiculed the young marchers as “infants whose mammas didn’t know they were out”, and threatened violence against them. But they were intimidated by the sight of thousands of young men, disciplined, standing up for their non-violent ideals.

The Wide Awakes were not, technically, a part of the Republican party. But they loved Lincoln, whose authenticity mirrored their own. Party leaders shrewdly adapted their message to the movement, which peaked in the fall, as the election approached. William Seward, soon to be secretary of state, gave a speech in Detroit promising that “the young men throughout the land are Wide Awake”. In Boston, Lincoln’s running mate, Hannibal Hamlin, marched through the street with “the boys”. On 3 October, a huge torchlight procession and pyrotechnic display dazzled New York City. Tens of thousands came out.

To be sure, these events were a kind of entertainment. But true to their banners, the Wide Awakes kept their eyes open as the great day of the election approached. Many served as “patrol-men” at voting stations, on guard against dirty tricks, determined to use “all honorable means” to ensure a fair count.

It worked, and Lincoln’s victory owed something to tremendous support from the young. Estimates vary, but as many as half a million young men may have joined the movement, and the number rises quickly when spectators are added.

After Lincoln’s election, the Wide Awakes faded away, as mysteriously as they assembled, but they had accomplished something important. When Lincoln was inaugurated on 4 March – a year to the day after the Clotilda sailed from Alabama – America had come a long way toward reclaiming its ideals. A last contingent of Wide Awakes attended his inauguration, determined to shield him from harm.

Nowadays, the Wide Awakes occasionally resurface in the history books, including a study by Jon Grinspan and a book by Adam Goodheart. Sometimes, they are awakened accidentally – as when the Florida representative Matt Gaetz, a Trump ally, denounced young people as “woketopians” during an angry speech at the Republican convention. But they will always live on in haunting photographs, lingering evidence of a generation that stood up to reclaim its democracy.

Tеd Wіdmеr

Library of Congress

Portions originally published on The Guardian as Wide Awakes: the Lincoln-era youth movement inspiring anti-Trump protests

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.