Experts say hospital ICU stays, often faced alone, bring mental health woes to older patients in particular.

For 70-year-old Charlene Fugate, the trouble started in March with a persistent respiratory infection that required two courses of antibiotics plus an inhaler to help her breathe. After several days, she realized she “was having a harder and harder time” holding her breath for the 10 seconds it took for the steroids to reach her lungs.

By the time her husband took her to the Indiana University Health West Hospital, she was also experiencing headaches, fever and coughing. Within 21/2 to three hours of walking into the ER, Fugate was on a ventilator, with an IV, feeding tube and catheter, and was being transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) at IU Health Methodist Hospital with a diagnosis of COVID-19.

She spent three days in the ICU and another four days in a different unit in the hospital before going home. Yet three months later, her recovery is still a work in progress. In addition to feeling weak and short of breath at times, Fugate is struggling with getting over what she went through emotionally.

Soon after she left the hospital, Fugate started having flashbacks of her time in the ICU — fragments of memories that she describes as distressing and frightening. And she is haunted by the memory of having to text her family, waiting outside the hospital ER admissions area, to tell them that she was being ventilated, and of worrying she’d never see them again. Not remembering what happened from there also unnerves her.

“I lost track of basically three whole days,” she said. “I know that I was taken care of and I had nice nurses, but I really don’t know what all happened during those days.”

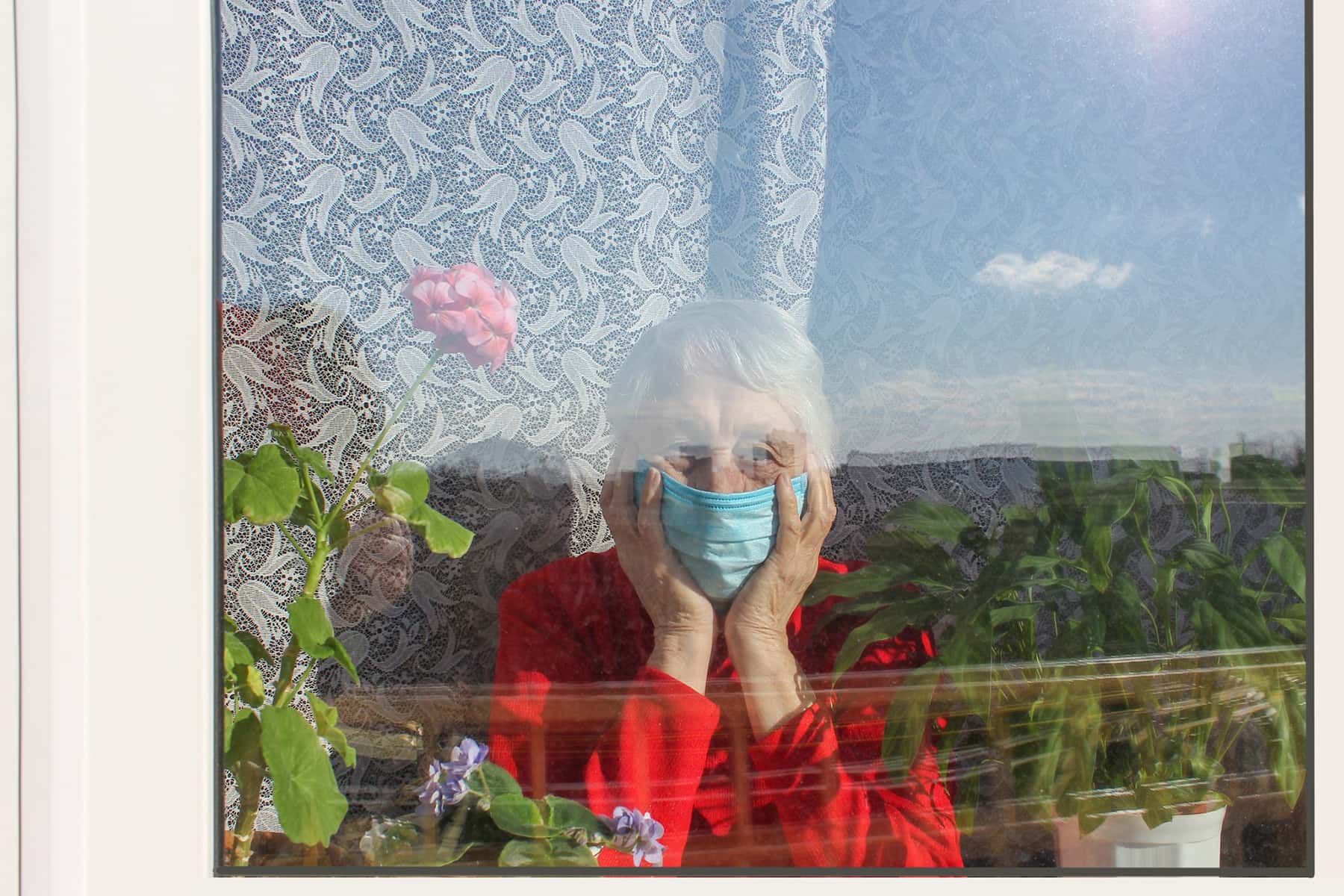

Although Fugate survived the worst ordeal of her life, she also lives with the overwhelming fear that she will get sick again — since no one yet knows whether having COVID confers immunity to the disease.

“Leaving the kids and my husband — I’m not ready to do that yet,” said Fugate, who has returned to her job as an accounting coordinator. “I work with a lot of kids, 20- and 30-year-olds, and they seem not to take it as seriously as us older people. Did they social distance? Do they wear their masks outside of here? Do they keep track of their vital signs?”

Fugate is on an antianxiety medication and has talked to a hospital chaplain about her near-death experience. “

She told me I’m suffering from a form of grief and a form of PTSD,” she sid.

Fugate’s story is becoming a familiar one among COVID patients, particularly those who spent time in intensive care. Anyone who has been in the ICU is prone to long-term emotional, cognitive and physical problems, collectively termed post-intensive care syndrome (PICS)

“It is a very common condition where patients and their caregivers experience quality-of-life impairment for up to two years after surviving critical illness,” said Sikandar H. Khan, an osteopathic doctor, pulmonologist and critical care physician who oversees the Critical Care Recovery Center at IU Health in Indianapolis, one of a growing number of clinics focused on the long-term health problems of ICU patients.

“While the priority of health providers in the hospital is rightly keeping patients alive, we know from other respiratory failure survivor populations, such as influenza, bad bacterial pneumonia and sepsis, that patients will have a lot of mood symptoms,” Kahn said. “And we are seeing similar things in COVID survivors.”

A ‘perfect storm’ for mental health woes

About 30 percent of ICU patients experience new or worsened anxiety symptoms, between 25 and 30 percent report symptoms of depression, and 20 percent have symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), says Megan Hosey, a rehabilitation psychologist and assistant professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

In addition, Hosey said, studies suggest up to a third of people [treated in an ICU] also experience symptoms similar to moderate traumatic brain injury, a rate similar to soldiers coming back from war zones. This may include memory lapses and weakened “executive function” skills like planning and problem-solving.

Such issues may be magnified among patients who experience delirium, a state of confusion and disorientation that is often accompanied by delusions and hallucinations.

“Patients will often have really vivid perceptual distortions,” said psychologist James Jackson, assistant director of the ICU Recovery Center at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. “Rather than not remembering anything, they often remember things that actually didn’t happen, or things that actually did happen but they have a distorted interpretation of them. That then becomes the basis of a pretty meaningful trauma for them.”

Delirium is especially common among people who are sedated, as COVID patients on ventilators in critical care units tend to be. In fact, all of the persistent problems associated with ICU stays may be compounded among COVID patients, according to experts.

“COVID tends to be marked by things like longer stays on mechanical ventilation and longer stays in the ICU,” Jackson said. “Even without COVID, those things are super-problematic.”

And because of the contagiousness of the virus, patients are largely alone when they’re fighting for their lives.

“The majority of ICU patients are greatly aided by the presence of their families, but with COVID there are no family members at the bedside,” Jackson said. “Patients report feeling forlorn and forgotten. It’s a perfect storm for an emotional crisis.”

The sudden onset of severe COVID symptoms doesn’t help matters. With many potentially deadly diagnoses, like cancer, there is a longer arc to the disease that allows patients to adjust and adapt.

The struggle after the illness

After discharge, patients must come to terms with a new reality, especially if they are dealing with physical limitations. “For some of our older patients who are nearing retirement, the future doesn’t look quite as bright as it might have pre-COVID,” Kahn says. Overshadowing many patients’ recovery is the fear of becoming infected again.

That is why ICU recovery clinics take a holistic approach to treating COVID and other patients, with physicians, nurses, pharmacists, psychologists, physical and occupational therapists and even chaplains playing a role.

For example, “patients often report anxiety in the context of breathlessness,” Hosey said. “A psychologist needs to partner with a physical therapist or physician to figure out how can we build your strength back carefully, because what’s going to reduce anxiety is having experiences of success while challenging yourself under guidance.”

At IU Health, mindfulness program director John Shepard might prescribe calming breathing techniques. “But you first teach the patient that feeling anxious is completely normal, especially when you’ve been through a traumatic experience,” he said.

The good news is that mental health problems of this type are fairly treatable with a variety of types of therapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), offering most patients relief from their feelings of sadness and anxiety. Anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medications can decrease mood symptoms, when prescribed correctly. Some centers also offer psychologist-led support groups that help patients understand that they’re not alone.

For Charlene Fugate, time has brought gradual improvement. She is getting stronger and is being weaned off the supplemental oxygen she needed when she first left the hospital. And slowly she is regaining her emotional equilibrium.

“My coworker told me I am a lot calmer now,” she said. “I’m slowly getting back to me.”

Beth Howard

Portions originally published on aarp.org as COVID Survivors Face PTSD, Anxiety