Milwaukee activist Annia Leonard wants a safe community without police, and she draws from her own experience when thinking about what that could be: like the time a conflict at her grandmother’s house ended peacefully in a garden — without anyone in handcuffs.

When an argument escalated earlier this summer, one person in the house called Milwaukee police, Leonard said, and someone else called 414LIFE — a team of community “violence interrupters” who are trained to intervene. With her adrenaline pumping, Leonard said she was already in “fight mode” when the officers arrived, and their response only antagonized those involved in the dispute, adding to the stress.

“We didn’t need someone to come say that we could all be arrested,” she said. “They talked to everyone individually. They were just making sure that everyone in the space was good.”

The violence interrupters quickly dissolved that tension once they arrived, Leonard said, and it helped that some people in the house knew one team member.

“It was just a completely different approach to domestic violence that a lot of people aren’t usually privileged to see,” said Leonard, who aims to uplift Milwaukee’s Black residents in her own organizing work — holding healing events and calling for the abolition of police. “It just made it clear, this is why we don’t need police officers in our communities.”

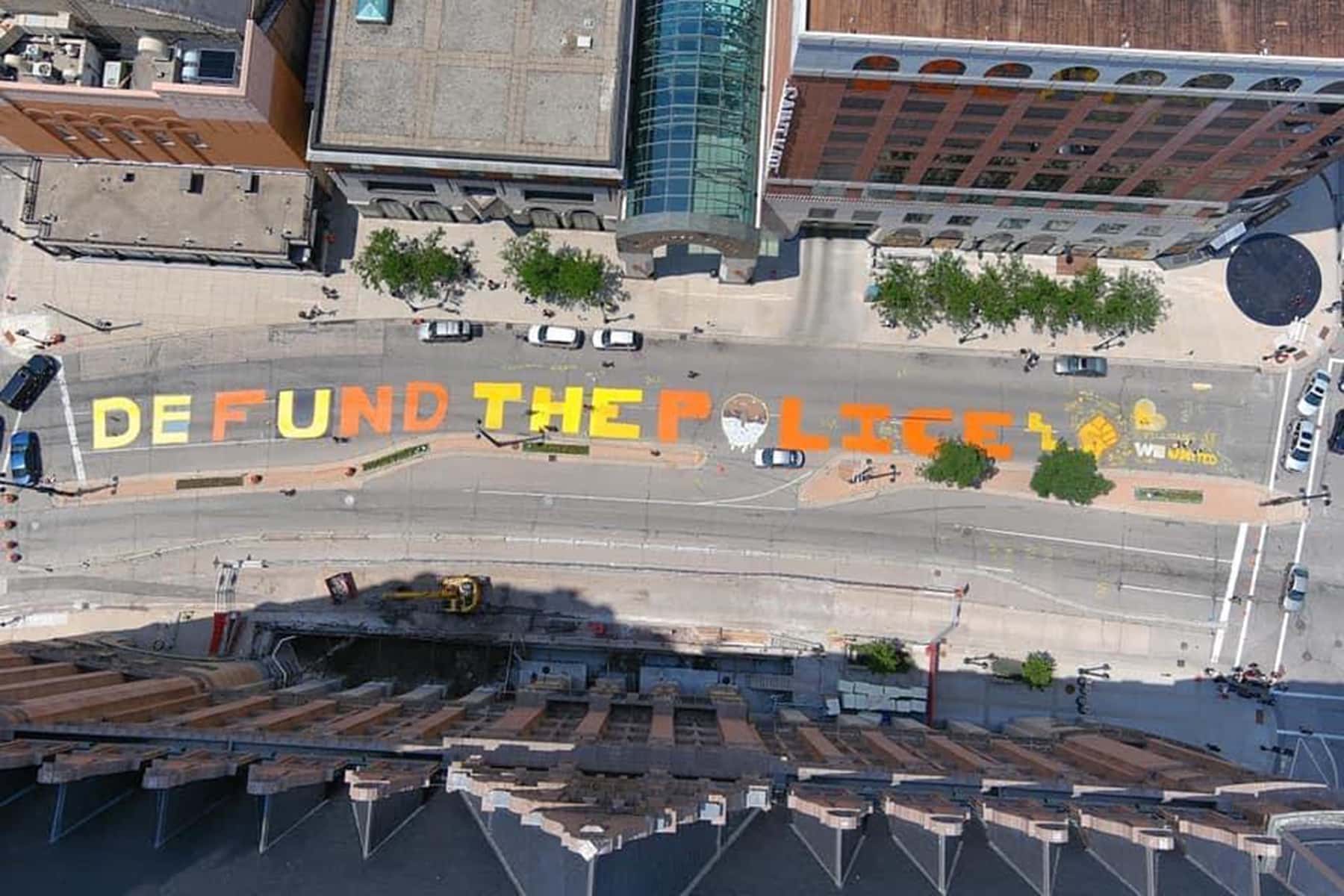

Calls to “defund the police” have grown louder in Milwaukee and other cities after the May 25 police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis fueled nationwide protests against police brutality and systemic racism.

Floyd’s death came as Milwaukee grieved the loss of Joel Acevedo, who died days after Michael Mattioli, an off-duty Milwaukee police officer, acknowledged putting him in a 10-minute chokehold during an April fight, according to media reports. Mattioli was charged with first-degree reckless homicide, and the department suspended him with pay.

Some say the goal of “defunding the police” is to shift funds away from police and towards public health, housing and other programs to alleviate conditions that lead to crime. But many local and national advocates eye a more ambitious goal: to abolish police over time. Abolitionists see reallocation as the first step toward dismantling policing and prison institutions, replacing them with neighborhood-based public safety models.

Milwaukee’s defunding movement comes as city officials set next year’s budget, and the police department wants to grow its slice of the pie. Meanwhile, a coronavirus pandemic is wreaking havoc on the economy, promising to slash city revenue and leave less money for a host of government services.

“Even if the tragic death of George Floyd and nationwide protests had not occurred, there was very good reason for citizens and policymakers to take a look at the Milwaukee Police Department budget, and that has nothing to do with any kind of opinion or bias with putting municipal budgets into police departments,” said Rob Henken, president of the Wisconsin Policy Forum, who noted that Milwaukee faced “tremendous economic stress” even before the pandemic.

The conditions and debate transcend Milwaukee. During calls to divest from police, the Madison School Board in June voted to terminate its Madison Police Department contract for resource officers at high schools. Critics of the officers’ presence highlighted disproportionate arrest rates for Black students and said the school should handle discipline outside of the criminal justice system.

‘We didn’t get here overnight’

Law enforcement in 2018 accounted for nearly 22% of Milwaukee’s $1.4 billion in total expenditures — the largest category in the budget, according to Wisconsin Department of Revenue data. That hovers above law enforcement’s 20% share of municipal spending statewide, according to a Wisconsin Policy Forum analysis of state data.

The Milwaukee Police Department consumes an even bigger share of the city’s general purpose budget — the portion controlled by the mayor and Common Council. MPD accounted for about 47% of that spending in 2020, up from 40% in 2012, according to the Wisconsin Policy Forum. The police budget in each of the last five years has eclipsed the city’s entire property tax levy, one of three main revenue sources. Nearly 95% of the police budget funds salaries, wages and benefits.

MPD is requesting nearly $316 million for next year as Milwaukee wades into the country’s worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. That proposed $18.5 million increase from last year is 20 times the Milwaukee Health Department’s $15.7 million request.

The health department houses the $2.1 million Office of Violence Prevention, which encompasses the 414LIFE team, a small-scale example of policing alternatives.

The team is trusted in the neighborhoods it engages, said Derrick Rogers, program director for 414LIFE. It is among groups globally that practice an evidence-based “Cure Violence” model that sees violence as a treatable epidemic. The 414LIFE team aims to stabilize people deemed at high risk of committing violence, helping them secure housing, jobs, therapy and relationship support. The interrupters check in with people involved in disputes — even months after they defuse them.

When Rogers responded to the dispute at Leonard’s grandmother’s house, he helped one person pull weeds in a garden while talking through the frustrations that fueled the conflict. They constructed a plan to avoid future conflict and discussed how to file a restraining order. Rogers later called the person’s friends and offered connections to mental health providers.

But Milwaukee is spending roughly $504 per resident on policing compared to less than $4 per resident on such direct violence prevention.

“We didn’t get here overnight,” Reggie Moore, director of the Office of Violence Prevention, said this month during an online Wisconsin Police Forum event. “These were generations of decisions and policymaking and investment where unfortunately a lot of cities and counties responded to situations of community crisis with greater investment in law enforcement, versus looking at public health and taking more innovative approaches.”

Grassroots organizers have spent years helping Milwaukee residents envision such an approach in a city that last year declared racism a public health crisis and saw annual eviction rates of up to 15% of households in some neighborhoods — even before the pandemic left thousands jobless and waiting on rent assistance.

“How do we address the root causes of the trauma and pain that we’re seeing as opposed to trying to manage it with punishment and the criminal justice industry?” added Moore added.

Calls to shift funding grow

Common Council members last month reported a flood of constituent requests to “defund the police.” The council on June 16 approved a resolution to study a 10% cut to the MPD budget — about $30 million. The Milwaukee School Board two days later unanimously resolved to remove police officers from public school grounds.

That’s not enough for advocates such as Markasa Tucker, director of the African-American Roundtable, a coalition serving Milwaukee’s Black residents. The coalition and other groups are calling for a $75 million cut to MPD’s budget that would shift $50 million to public health and $25 million to housing cooperatives in a campaign called LiberateMKE.

“These are our tax dollars. This is our money, and we get to say where we want it to go,” Tucker said at a June Facebook event.

The campaign is one step toward a longer-term goal of upending the city’s approach to public safety, said Devin Anderson, lead organizer for the LiberateMKE campaign.

“We believe a world without police is possible,” he said. “Defund is the goal, and divestment is the process.”

Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett will begin holding budget hearings in August and plans to present his budget to the Common Council in September.

“The funding of our police department is one aspect of the review, but a funding cut, alone, does not address a multitude of other issues we must consider,” Barrett said in a June statement. “Our upcoming budget process is an opportunity to take a comprehensive look at how city government views public safety.”

Crime surges following decline

The conversation unfolds as homicides in Milwaukee are surging to levels not seen since the 1990s following a four-year decline — a trend playing out nationwide during the pandemic. Violent crime does not necessarily correlate with a need for police officers, the Wisconsin Policy Forum noted in a 2019 report showing how Milwaukee and some other Wisconsin cities are boosting police spending even as they lose officers.

“Defund” advocates say many factors outside of law enforcement affect crime rates and create safety, and Milwaukee has never invested to scale in community-based strategies to keep people safe without police.

Monique Liston, chief strategist at Ubuntu Research and Evaluation, a Black women-led consulting firm for education, policy and advocacy, underscored that societies haven’t always relied on police, and that many of America’s police systems were created to control Black people and protect the interests of the wealthy.

“Policing was built around protecting stolen property and protecting stolen people,” she said. “One of the big disservices we’ve done in history is to act like police are a natural part of organizations. It’s so ingrained in people that police have to be there.”

Distrust of Milwaukee police not new

Distrust of police runs deep in some of Milwaukee’s Black and brown-majority neighborhoods, and some residents are tired of waiting on piecemeal reforms to change policing tactics that have disproportionately harmed people of color.

“Reforms like banning chokeholds, adding body cameras and that we need more trainings — in many ways those are not enough,” said Anderson of LiberateMKE. “By investing so much in a system that was never meant to keep us safe, that’s leaving no space and no room for the other investments, and it’s hurting us. In some cases, it’s literally killing us.”

Milwaukee police officers have for years been the subject of reform debates and criminal and civil proceedings, including after the police killings of Dontre Hamilton in 2014, Sylville Smith in 2016 and Acevedo.

Recommendations have followed — from the U.S. Department of Justice in 2017 and the city-convened Collaborative Community Committee in 2019. But the city has yet to implement many such proposals. Barrett in June announced yet another reform commission, which some activists viewed as déjà vu.

Milwaukee’s Fire and Police Commission, a civilian oversight board with the power to change policy and investigate complaints, this week issued a set of directives to Morales demanding changes. The commission itself faces allegations that it acts slowly and lacks transparency.

“We’re constantly being put where we’re in the position for these tough conversations needing to hold cops accountable,” Leonard said. “I’m not trying to demand reform from them anymore. The whole system needs to be abolished.”

Stop-and-frisk persists

In 2018, Milwaukee’s Common Council approved a $3.4 million settlement of a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union. The group alleged Milwaukee’s stop-and-frisk program led to unjustified stops, racial profiling and harassment of residents without cause for suspicion.

In a June report monitoring the department’s progress on the settlement, the Boston-based Crime and Justice Institute found that officers undercounted frisks and failed to properly justify 81% of documented frisks during the second half of 2019, showing no improvement on those measures from earlier in the year.

The report also showed that officers stopped and searched Black people at disproportionately high rates. Black residents make up roughly 39% of Milwaukee’s population but faced nearly 60% of police encounters and 80% of frisks.

“They’re not really living up to their end of the bargain,” said Molly Collins, associate director of the ACLU of Wisconsin. “It can be the police firing tear gas or rubber bullets at protesters, but also it just looks like continued patterns of police interactions with Black and brown folks that continue to break the relationship between the police department and the community.”

Said Grant, the MPD spokeswoman: “Our members continue to receive training, and MPD continues to make progress in our compliance efforts.”

‘The community knows what keeps them safe’

Fueled by frustration with Milwaukee’s status quo, neighborhood leaders have long brainstormed ways to reinvest funds flowing to police. One tiny example: When Anderson would wrap up LiberateMKE’s meetings last year at city public libraries, he noticed the buildings would stay full until closing time, with staff asking people to leave.

“What if we took money from the police for that?” he said, suggesting staffing the libraries for longer hours.

LiberateMKE encourages residents to envision new uses for their tax dollars. The coalition surveyed more than 1,100 residents in that process. Last year’s participants recommended rerouting $25 million from MPD to community-based violence prevention programs such as 414LIFE. They also called for bigger investments in employment opportunities for young people and affordable, quality housing.

Many of those recommendations referenced the Office of Violence Prevention’s 2017 Blueprint for Peace, a set of community-driven goals and recommendations.

That involved hundreds of community members who sought to identify the root causes of Milwaukee’s violence. Among those flagged: lack of quality, affordable housing, neighborhood disinvestment, limited economic opportunities and persistent trauma. Participants determined what Milwaukee should leverage to make neighborhoods more resilient, including already strong community-building groups, schools, arts and cultural expression and welcoming public spaces.

The blueprint spurred the creation of 414LIFE and other investments in youth programming, mental health and domestic violence prevention.

“We understand that when we look at the production of public safety in our city, it really takes beyond policing and the criminal justice industry, and I think that’s really what this movement and moment is challenging us to think about,” said Moore, the Office of Violence Prevention director. “When we look at neighborhoods throughout the city and throughout the country where large police presences aren’t required, those communities tend to have thriving businesses. They have thriving families who are gainfully employed.”

Moore said Wisconsin leaders should help Milwaukee and other cash-strapped cities invest in violence prevention.

State Representative David Bowen and State Senator Lena Taylor, both of Milwaukee, and other Democratic lawmakers in March proposed funneling tax revenue from vaping products into a statewide violence prevention fund. The bill failed to draw a hearing. Other Milwaukee groups have helped lay the groundwork for this moment.

Black Leaders Organizing for Communities, which aims to invest in and empower Milwaukee’s Black residents, released a 2019 Platform for Prosperity. It incorporates voices from thousands of who responded to the question: “What would it look like for your community to thrive?”

The group is now surveying residents — online and via text — about their vision for policing. Rick Banks, the group’s political director, said support is growing to defund MPD.

“Police brutality and things have been an issue for generations, but right now the energy around it, coupled with the budget cycle, is a huge opportunity for people to explore that idea,” he said. “It doesn’t feel like a far-fetched idea.”

The pandemic has added momentum to the push for change, said Liston of Ubuntu Research and Evaluation.

“I don’t think a lot of people knew how badly these systems were failing people, and it took a pandemic for people to realize how bad things are,” she said.

The virus is disproportionately infecting and killing Milwaukee’s people of color, and it is worsening economic hardship and flooding courts with eviction cases. Even before the pandemic, about half of Milwaukee renters paid more than 30% of their income in rent, according to a 2018 report from the Wisconsin Policy Forum. The same report showed 42% of the city’s renter households earned less than $25,000 a year, while only 9% of rental units charged rents considered affordable to those households.

The pandemic is also spurring more grassroots efforts to provide food, financial help, child care and other services — proving that residents can take care of each other, Anderson said.

“Mutual aid, that is community care. That is community safety,” he said. “Those are people on the ground making sure that people’s needs are met by offering support to their neighbors. The community knows what keeps them safe.”

Allison Dikanovic

Will Cioci and Honni Al-Juma

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.