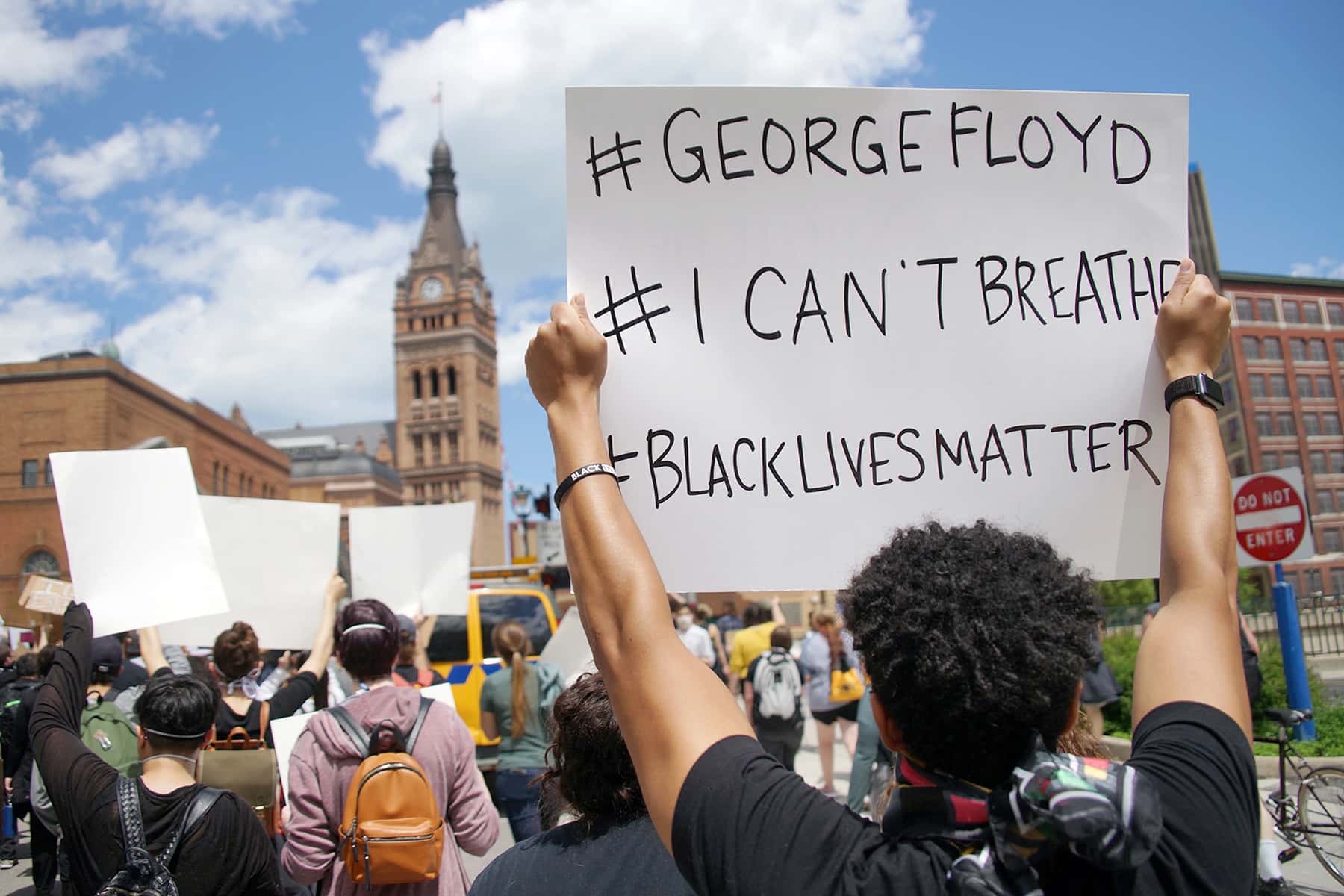

“There’s definitely something going on,” said 39-year-old Milwaukee activist Frank Sensabaugh, better known locally by the long-held nickname “Frank Nitty.” Most of his days recently have been spent either organizing or participating in Milwaukee’s slice of the nation’s re-invigorated Black Lives Matter movement. Nitty, and many others, also suspect the demonstrations have become the targets of electronic surveillance.

For Nitty, it started with difficulty livestreaming the events from his Facebook page. “They do that a lot, live feeds will cut out,” he said. “It’ll start getting blurry … or sometimes I’ll be live and I’ll be talking, and my mouth is moving slower, so I know it’s about to start.” Even if a video has nearly 1,000 viewers, Nitty will watch as their numbers decline before the feed cuts. “The most amazing thing about it is the convenience of the times that it happens,” said Nitty. “It always happens when something’s about to go down.”

Nitty and other activists have reasons to feel suspicious. There is a long history of surveillance targeting Black activists in the United States, stretching back to the civil-rights movement, and continuing through modern Black Lives Matter protests nationwide.

When Milwaukee residents first took to the streets on May 29, they encountered dozens of police officers, many in riot gear. Although police blocked the highways and side streets, they allowed marchers to walk the roadways unchallenged. Drones, however, still maintained a close watch overhead as night fell. Later that evening, police and residents clashed as marchers gathered at the Milwaukee Police Department’s (MPD) District 5 station. Pepper spray and gas were used, and at least 16 nearby businesses were looted in the post-midnight hours.

Rafael Smith, a resident who lives near the station, went out to see the standing protest for himself. Smith noticed his livestream began to fail, “I tried to [go] live like 50 times,” he said. “Especially when I got about 20 ft from the [police] building.” Drones diligently hovered overhead as riot police held a line below. Officers also had positioned snipers on the station’s roof. “I was able to start it but as I got closer to film, it would begin buffering,” Smith recalls. “That’s why all my clips were less than one minute. Something was up.”

The next couple of days brought in the National Guard and an augmented police presence. The air traffic at that point included a UH-60 Blackhawk helicopter flown by the National Guard, with an MPD member on board. One man is now facing federal charges for shining a laser pointer at a Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) surveillance plane and a helicopter as they flew overhead. When the curfew ended, the police posture did not de-escalate.

Tear gas and rubber bullets were fired on multiple occasions and prominent marchers faced arrest, Nitty among them. Following these escalations, and even before the first clashes on May 29 to 30, protesters whispered about what they felt were suspicious phone malfunctions.

Law enforcement have a plethora of tools to monitor people and their communications. Wholesale government collection of private data has been an uncomfortable open secret since Ed Snowden’s National Security Agency (NSA) revelations. Federal and local law enforcement also have access to cell site simulators. The devices are also known as Stingrays after a particular brand name of the devices produced by the Harris Corporation, a defense company.

Stingrays produce spoof cell towers which force devices to connect to them before being routed to the real tower. These man-in-the-middle attacks allow police to access phone data such as location, but can also intercept calls and communications. Stingrays are also known to cause network service issues, block 3G and 4G connections and drain the batteries of the targeted devices. MPD uses them, as do numerous departments in Wisconsin.

The shadowy devices come with non-disclosure agreements barring police from revealing their use in certain circumstances.

MPD would not discuss its strategies involving Stingray but did state, “this technology was not used during the protest.” Gillian Drummond, spokeswoman for the state Department of Justice (DOJ) noted, “cell phone tracking technology is only used with the oversight of a judge through a court order, except in rare exigent circumstances of ongoing, life-threatening crime, such as an amber alert or active shooter. Wisconsin DOJ does not use this technology as part of surveillance.”

In 2016, however, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Wisconsin found the MPD had hidden its use of Stingray from courts. Police would not reveal how they had located a defendant, using “oddly vague language to explain how they had located him,” the ACLU noted. One officer merely wrote the information had been “obtained,” and another said police, “obtained information from an unknown source.”

The ACLU publicized a list obtained by privacy activist Mike Katz-Lacabe of 579 investigations in which the Milwaukee Police Department used its Harris Corp. Stingrays, including it in the ACLU court filings. “Evidence of police hiding their Stingray use from defense attorneys, judges, and the public is widespread,” the ACLU stated.

The MPD denies that this technology was used during Milwaukee’s marches. The city’s protesters remain suspicious that they are being monitored. Samarra Beans, a protester in her early 20s, had an experiences during the first couple of days of demonstrations. Her particular march was routed like a circle, from 27th Street and Capitol Drive towards the courthouse. Marchers had attempted to demonstrate on the freeway, which officers have focused particular attention on preventing.

“I had been trying to share live videos,” she said. “I could only get one of them to work, and it’s only a few minutes long before it dropped itself. Every single video I started streaming live over Facebook was not streaming. The first video I tried ran for about six minutes, and suddenly crashed. Every video after that one would not even start sharing. The stream wouldn’t turn on.”

Meanwhile, her battery was draining unusually fast. “My phone then turned off completely for the entirety of the march,” Beans explained. “Once I was on the bus going home, my phone turned on and was on 7%. This doesn’t happen with my phone.”

Protester Josh Wilke experienced similar issues, particularly after the National Guard and curfew were activated. “I can attest that when the Blackhawks are in the air, live feeds go down and internet speeds slow or cease outright,” Wilke said. “Phone calls are almost impossible to place or receive.”

Wilke, who works as a security installer, said the chilling effect the livestream failures had was palpable. “When a livestream we were watching would go down,” he said, “you could see everyone get a little more anxious.” He noticed, “the live feeds would go down first and you see some of the crowd respond to that. Then about 20 seconds later either you couldn’t take or receive calls or texts.”

Wilke also noted that, “phone calls would drop, and then my phone would state I had no service reception when I had full bars 30 seconds ago. In the city, some spots are spotty for coverage, but they are consistent. Not dropping from 100 to zero at random. It was also impossible to access data, and this denial of service could last up to 10 minutes depending on what the flight plan was.” Nitty has also observed that the malfunctions seemingly defy Milwaukee’s known signal “dead zones.”

“I’ve had this particular iPhone for about two years, and it’s never done this,” said Nitty. “And it’s crazy because I live in these areas. So it’ll be an area that I’m always at, and I’ve always been at … It’s just strange.” Nitty said the phenomena has also followed him home outside the marches. “For my particular device, it goes dead when others don’t. I’ll lose my signal now all the time since this [the protests] have been going on. I’ll be live, I’ll go somewhere, and I’ll just lose my signal. Sometimes I just can’t even go live.”

In response to the reports from Milwaukee, a Facebook company spokesperson said, “I can confirm that there were no technical issues we could detect on our side that would have prevented people from going live on Facebook.”

Katz-Lacabe said there can be other explanations for why marchers are experiencing issues while in large groups. “While it’s good to have a healthy dose of paranoia about surveillance by police, a more likely explanation is that when large groups of people congregate, they can overload the nearest cell phone tower.” To compensate, the tower may direct people’s phones to the next nearest tower. “This can result in poor connections, no connection at all, increased latency and high battery drain as a phone strains to reach a cell phone tower that is farther away.”

That however, only applies to some of Milwaukee’s reports. “These devices are shrouded in such secrecy that it’s certainly possible that the same police who are violently attacking protesters and journalists could wreak havoc with a CSS [cell site simulator],” said Katz-Lacabe.

Even as he have his interview outside the MPD’s downtown headquarters, awaiting a lightly attended press conference without a march in sight, Nitty’s phone drained from full power to 1% in less than an hour. He has also noticed, “whenever I call it’s not right away anymore. It takes about 45 seconds.” This phenomenon among the marchers is coupled with known surveillance and investigations into the protests by federal authorities. Milwaukee residents have reported visits from the FBI since the marches began.

District 4 Milwaukee County Supervisor Ryan Clancy is among them. Clancy was visited after being arrested on the night of curfew. As a county supervisor, however, Clancy was supposed to be immune to the order. Following his release, Clancy posted on social media that FBI agents had visited him to ask about the protests. Clancy denied seeing any illegal or violent activity on the part of the demonstrators, he posted. While he was in custody, Clancy also said officers appeared interested in accessing his phone.

“After I’d been taken into custody,” Clancy said, “it seemed like nobody wanted to be the name on my arrest record. They kind of passed me around to different people, and they kept asking me, ‘who arrested you?’” The arresting officer never identified himself, so Clancy did not know. “But at some point, they’d already taken my phones, and they asked me to unlock my phone so they could check to see who arrested me. And that threw up a lot of red flags for me.”

Although he refused, Clancy recalls, “they persisted in a way that led me to believe that it wasn’t them trying to get information about who arrested me, which I would think they would have anyways. But that they were trying to get access to the footage on those cameras.” Clancy said the officer’s attempts “really worried me” and that, “I hold my police to a higher standard than that. And we all should.”

District 3 Alderman Nik Kovac has been receiving concerning calls from residents who feel they have been placed under surveillance since the protests began. In one case Kovac received a communication from a community organizer who told him, “There’s cars in their alley and they look like they might be law enforcement … they’re a leader in the movement and they called me to say, ‘What do I do?’” Kovac suggested the person file a complaint, but saw how that could backfire. “It really is hard to follow up on these complaints without revealing who you are.”

After receiving more calls about possible surveillance, Kovac followed up with the MPD to see if investigators were making rounds. “The police said they don’t know anything about it,” said Kovac. “And I said, ‘well if you really don’t know anything about this, then we got a bigger problem because there’s someone out there impersonating the police.”

The relationship between the police and citizens doesn’t help either. Kovac notes that citizens may trust him, but they’re intimidated and don’t trust those he would end up asking to assist them. “It’s obviously hard to ask the police to investigate the police,” the alderman admits. He states it’s possible that local police don’t know anything because this may actually be federal surveillance activity.

A city with a history and surveillance

In 2016, after Jay Anderson Jr. was killed by a Wauwatosa officer, his family started protesting to demand justice. The 25-year-old’s death occurred in the wake of the unrest in Sherman Park that year, which resulted in $5.8 million in damages.

At the time, Jay Anderson Sr. and his wife Linda reported a variety of cell phone malfunctions. Looking out their windows, they recall seeing MPD vehicles both marked and unmarked parking on their block, seemingly watching them. In one instance, one of these vehicles rolled passed and the driver waved, Jay Sr. said. Once their son’s case concluded in late 2016, their sense that the family was being watched subsided until mid-June of this year.

The Andersons had heard of another family, the Coles, whose son was killed in February at Mayfair Mall by the same officer who killed Jay Jr. “Then, after we got a hold of the Coles and we found out they did it to them,” Jay Sr. said, “it started again, last week. My wife’s phone, my daughter’s phone, my phone. [They’re] scrambling and cutting off, cutting back on,” he said, adding that it’s become more difficult to send and receive calls and texts. Both the Cole and Anderson shootings were investigated by the Milwaukee Police Department.

The family of 17-year-old Alvin Cole reports dealing with these very same issues. For Tracy Cole, Alvin’s mother, it began shortly after her son was killed. First when she’d video chat relatives, her face would blur out, although the rest of the image remained clear. “And then one day I was talking on my phone,” said Tracy Cole, “and I could hear like a static. And now I can hardly hear off my phone anymore.”

The voice of the person she was talking to would also echo, she said. Loved ones began telling her that their calls were being redirected to a strange voicemail before failing.

The phone belonging to Alvin Cole’s sister, Taleavia Cole, began malfunctioning within the last couple of weeks. Her calls will fail “only to certain people,” she explained, specifically activists in the area. Taleavia Cole and her mother’s phone batteries have also been draining quickly. “Mine’s be like on 100%,” the senior Cole explained, “and then it just goes dead … my phone will freeze up.” Her phone has also taken pictures of her without her doing anything while calling family members. “It is kind of strange because this has never happened,” said Tracy Cole. Taleavia Cole’s phone is now also unable to connect to anything higher than 2G.

The family said they have also been followed by marked and unmarked cars. Both Nitty and Taleavia Cole note that their texts and calls to allies and loved ones cause the phones of who they’re communicating with to malfunction and drain as well. Other Milwaukee families have reported similar things in the past.

What — and who — could it be?

Peter Ney, a researcher at the University of Washington State, said that Stingray could be used on protesters.

“My guess is that, if they are used, then they will be used to try to figure out which phones are in a particular area. IMSI-catchers [Stingray] can be used to find specific people of interest or gather the phone identifiers to all people in an area.” Ney, who conducted a study to detect Stingray surveillance in Milwaukee and Seattle, said determining whether a spoof cell-phone tower was used can be tricky.

In the Coles’ case, Ney feels some of what they have experienced fits, but not everything. “The [report] about the battery draining quickly is interesting because the way that a lot of IMSI-catchers work is that they force a phone to transmit on a particular frequency at high power,” said Ney. “This can cause the phone to get hot and can drain the battery quickly.” Nevertheless, he admits, many malfunctions linked to Stingrays can also be explained by other means.

Milwaukee activists are on high alert lately, particularly since the National Guard, federal agencies and local police have all operated together in the city. Nitty said “it’s easy to say we [local police] don’t have it,” when it’s actually another assisting agency. Capt. Joseph Trovato of the National Guard said that the Guard was not operating independently, and was not jamming signals.

National Guard aircraft have monitored protesters in other states as well, but that surveillance craft monitoring the marches were not gathering “signals intelligence.” This refers to the interception of electronic communications and data. An MPD spokesperson released a statement that the department, “does not have the capability to block or jam cellphone signals. It is not our enforcement practice to block a signal as members of our community may need access to their phones for medical or emergency services.” MPD, however, would not comment on whether its Stingray technology may cause this when in use, as the devices are known to do.

The MPD spokesperson also added, in regards to the Cole and Anderson families, that they “could not find any information that would verify that MPD squads were monitoring Alvin Cole or Jay Anderson’s residences.” The denials, however, don’t put the families’ worries to rest.

Investigating the investigators

“It’s an invasion of privacy,” asserts Tracy Cole. “A person should be able to talk to family members and people about problems that are going on in my life. And you can’t even do that because they’re listening to my conversations.” For the Coles, the surveillance they’ve experienced only worsens the trauma of losing Alvin. “I don’t even talk to my family members who are out of town over the phone anymore.” Taleavia Cole finds it more difficult to focus on finishing college, and to trust people. She realizes that focusing too much on the surveillance only makes things worse.

Nitty believes that sometimes it was easier to keep the phenomenon to yourself. “People will think I’m a conspiracy theorist if I talk about this,” he said. “But the reality of the situation is that’s what’s been going on. You can’t deny the facts. You can ask anyone who’s been out here protesting and they’ll tell you that all that has happened … in areas where it’s never happened before.”

Clancy echoes the sentiment. “We don’t have to speculate about this,” the supervisor said. “Those budgets are public record. You can see the drones in the air, you see the helicopters, you can see a massive military response.” Clancy feels that “law enforcement has no legitimate interest in blocking information from getting out there. So I’m concerned both that they’re using technology to do that, and also using individual officers to try and access individuals’ data.”

Wilke feels the police need to be much more transparent about their use of surveillance technologies. “Especially since regulation of these technologies is essentially the Wild West at this moment,” said Wilke. “We need defined regulations of acceptable use of surveillance and appropriate boundaries for what is and is not permissible use. There are privacy concerns involved that sadly our legislators are either ill equipped or otherwise incapable of handling.” Wilke would prefer these surveillance technologies to be open source for anyone to learn about their functions, and for every use of these technologies to be documented.

Taleavia Cole calls for a city review of these reports, saying it is necessary. “We don’t know what to do,” she said. “We’re just people. We don’t know who to go to.” Kovac feels that with all the reviews of police behavior during the protests and their budget now happening, a closer look into surveillance reports by the city government could become possible.

“I think it’s overdue,” said Kovac. Given certain high-profile events, “and given some of the complaints I’ve been getting in the last week, I think we are overdue to investigate the investigators.”

Lee Matz

Originally published on the Wisconsin Examiner as Milwaukee protesters and residents feel they’re under police surveillance

Donate: Wisconsin Examiner

Help spread Wisconsin news, relentless reporting, unheard voices, and untold stories. Make a difference with a tax-deductible contribution to the Wisconsin Examiner